Old and New About Equidistant Sets and Generalized Conics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smooth Curve Interpolation with Generalized Conics R

Computers Math. Applic. Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 37-64, 1996 Pergamon CopyrightQ1996 Elsevier Science Ltd Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved 0898-1221/96 $15.00 + 0.00 S0898-1221(96)00017-X Smooth Curve Interpolation with Generalized Conics R. Qu Department of Mathematics, National University of Singapore Singapore 119260 matqurb~nus, sg (Received May 1995; accepted June 1995) Abstract--Efficient algorithms for shape preserving approximation to curves and surfaces are very important in shape design and modelling in CAD/CAM systems. In this paper, a local algorithm using piecewise generalized conic segments is proposed for shape preserving curve interpolation. It is proved that there exists a smooth piecewise generalized conic curve which not only interpolates the data points, but also preserves the convexity of the data. Furthermore, if the data is strictly convex, then the interpolant could be a locally adjustable GC 2 curve provided the curvatures at the data points are well determined. It is also shown that the best approximation order is (..9(h6). An efficient algorithm for the simultaneous computation of points on the curve is derived so that the curve can be easily computed and displayed. The numerical complexity of the algorithm for computing N points on the curve is about 2N multiplications and N additions. Finally, some numerical examples with graphs are provided and comparisons with both quadratic and cubic spline interpolants are also given. Zeywords--Generalized conics, Splines, Parametric curve, Recursive algorithm, Subdivision, In- terpolation, Difference algorithm. 1. INTRODUCTION High accuracy curve interpolation and approximation in both theory and applications using a variety of methods have been studied intensively in the approximation literature (cf. -

The West Math Collection

Anaheim Meetings Oanuary 9 -13) - Page 15 Notices of the American Mathematical Society January 1985, Issue 239 Volume 32, Number 1, Pages 1-144 Providence, Rhode Island USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of the Notices was sent to the press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society. Abstracts must be accompanied by the Sl5 processing charge. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence. Rhode Island. on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcements and the list of organizers of special sessions. -

PHD THESIS ISOPTIC CURVES and SURFACES Csima Géza Supervisor

PHD THESIS ISOPTIC CURVES AND SURFACES Csima Géza Supervisor: Szirmai Jenő associate professor BUTE Mathematical Institute, Department of Geometry BUTE 2017 Contents 0.1 Introduction . V 1 Isoptic curves on the Euclidean plane 1 1.1 Isoptics of closed strictly convex curves . 1 1.1.1 Example . 3 1.2 Isoptic curves of Euclidean conic sections . 4 1.2.1 Ellipse . 5 1.2.2 Hyperbola . 7 1.2.3 Parabola . 10 1.3 Isoptic curves to finite point sets . 12 1.4 Inverse problem . 15 2 Isoptic surfaces in the Euclidean space 18 2.1 Isoptic hypersurfaces in En ........................ 18 2.1.1 Isoptic hypersurface of (n−1)−dimensional compact hypersur- faces in En ............................. 19 2.1.2 Isoptic surface of rectangles . 20 2.1.3 Isoptic surface of ellipsoids . 23 2.2 Isoptic surfaces of polyhedra . 25 2.2.1 Computations of the isoptic surface of a given regular tetrahedron 27 2.2.2 Some isoptic surfaces to Platonic and Archimedean polyhedra 29 3 Isoptic curves of conics in non-Euclidean constant curvature geome- tries 31 3.1 Projective model . 31 3.1.1 Example: Isoptic curve of the line segment on the hyperbolic and elliptic plane . 32 3.1.2 The general method . 33 3.2 Elliptic conics and their isoptics . 34 3.2.1 Equation of the elliptic ellipse and hyperbola . 34 3.2.2 Equation of the elliptic parabola . 36 II 3.2.3 Isoptic curves of elliptic ellipse and hyperbola . 36 3.2.4 Isoptic curves of elliptic parabola . 37 3.3 Hyperbolic conic sections and their isoptics . -

Isoptic Curves of Generalized Conic Sections in the Hyperbolic Plane

Isoptic curves of generalized conic sections in the hyperbolic plane G´eza Csima and Jen˝oSzirmai, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Institute of Mathematics, Department of Geometry Budapest, P.O. Box 91, H-1521 [email protected], [email protected] April 5, 2019 Abstract After having investigated the real conic sections and their isoptic 2 curves in the hyperbolic plane H we consider the problem of the isoptic curves of generalized conic sections in the extended hyperbolic plane. 2 This topic is widely investigated in the Euclidean plane E (see for ex- ample [14]), but in the hyperbolic and elliptic planes there are few results (see [4], [5] and [6]). In this paper we recall the former results on isoptic curves in the hyperbolic plane geometry, and define the notion of the gen- eralized hyperbolic angle between proper and non-proper straight lines, summarize the generalized hyperbolic conic sections classified by K. Fladt in [8] and [9] and by E. Moln´ar in [17]. Furthermore, we determine and visualize the generalized isoptic curves to all hyperbolic conic sections. We use for the computations the classical model which are based on the projective interpretation of the hyperbolic geometry and in this manner the isoptic curves can be visualized on the Euclidean screen of computer. 1 Introduction arXiv:1504.06450v1 [math.MG] 24 Apr 2015 Let G be one of the constant curvature plane geometries, the Euclidean E2, the hyperbolic H2, and the elliptic 2. The isoptic curve of a given plane curve is the locus of points P G,E where is seen under a given fixed angle α (0C <α<π). -

On Equidistant Sets and Generalized Conics: the Old and the New

On equidistant sets and generalized conics: the old and the new Mario Ponce Patricio Santib´a˜nez Abstract This article is devoted to the study of classical and new results concern- ing equidistant sets, both from the topological and metric point of view. We include a review of the most interesting known facts about these sets in Euclidean space and we prove two new results. First, we show that equidistant sets vary continuously with their focal sets. We also prove an error estimate result about approximative versions of equidistant sets that should be of interest for computer simulations. Moreover, we offer a viewpoint in which equidistant sets can be thought of as a natural gener- alization for conics. Along these lines, we show that the main geometric features of classical conics can be retrieved from more general equidistant sets. 1 Introduction. The set of points that are equidistant from two given sets in the plane appears naturally in many classical geometric situations. Namely, the classical conics, defined as the level sets of a real polynomial equation of degree 2, can always be realized as the equidistant set to two circles (see Section 2). The significance of conics for the development of Mathematics is incontestable. Each new progress in their study has represented a breakthrough: the determination of bounded area by Archimides, their idea as plane curves by Apollonius, their occurrence as solutions for movement equations by Kepler, the development of projective and analytic geometry by Desargues and Descartes, etc. In another, let us say, less academic field we find equidistant sets as con- ventionally defined frontiers in territorial domain controversies. -

The Complex Geometry of Blaschke Products of Degree 3 and Associated Ellipses

Filomat 31:1 (2017), 61–68 Published by Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, DOI 10.2298/FIL1701061F University of Niˇs, Serbia Available at: http://www.pmf.ni.ac.rs/filomat The Complex Geometry of Blaschke Products of Degree 3 and Associated Ellipses Masayo Fujimuraa aDepartment of Mathematics, National Defense Academy, Yokosuka 239-8686, Japan Abstract. A bicentric polygon is a polygon which has both an inscribed circle and a circumscribed one. For given two circles, the necessary and sufficient condition for existence of bicentric triangle for these two circles is known as Chapple’s formula or Euler’s theorem. As one of natural extensions of this formula, we characterize the inscribed ellipses of a triangle which is inscribed in the unit circle. We also discuss the condition for the “circumscribed” ellipse of a triangle which is circumscribed about the unit circle. For the proofof these results, we use some geometrical properties of Blaschke products on the unit disk. 1. Introduction A bicentric polygon is a polygon which has both an inscribed circle and a circumscribed one. Any triangle is bicentric because every triangle has a unique pair of inscribed circle and circumscribed one. Then, for a triangle, what relation exists between the inscribed circle and the circumscribed one? For this simple and natural question, Chapple gave a following answer (see [1]): The distance d between the circumcenter and incenter of a triangle is given by d2 = R(R − 2r), (1) where R and r are the circumradius and inradius, respectively. The converse also holds. Moreover Poncelet’s porism ([3]) guarantees that there are infinitely many bicentric triangles, if the circumradius and inradius satisfy the Chapple’s formula (1). -

Conic Sections Beyond R2

Conic Sections Beyond R2 Mzuri S. Handlin May 14, 2013 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 One Dimensional Conic Sections 2 2.1 Geometric Definitions . 2 2.2 Algebraic Definitions . 5 2.2.1 Polar Coordinates . 7 2.3 Classifying Conic Sections . 10 3 Generalizing Conic Sections 14 3.1 Algebraic Generalization . 14 3.1.1 Classifying Quadric Surfaces . 16 3.2 Geometric Generalization . 19 4 Comparing Generalizations of Conic Sections 23 4.1 Some Quadric Surfaces may not be Conic Surfaces . 23 4.2 Non-Spherical Hypercones . 25 4.3 All Conic Surfaces are Quadric Surfaces . 26 5 Differential Geometry of Quadric Surfaces 26 5.1 Preliminaries . 27 5.1.1 Higher Dimensional Derivatives . 27 5.1.2 Curves . 28 5.1.3 Surfaces . 30 5.2 Surfaces of Revolution . 32 5.3 Curvature . 36 5.3.1 Gauss Curvature of Quadric Surfaces . 40 6 Conclusion 46 1 Introduction As with many powerful concepts, the basic idea of a conic section is simple. Slice a cone with a plane in any direction and what you have is a conic section, or conic; it is straightforward enough that the concept is discussed in many high school geometry classes. Their study goes back at least 1 to 200 BC, when Apollonius of Perga studied them extensively [1]. We can begin to see the power of these simple curves by noticing the diverse range of fields in which they appear. Kepler noted that the planets move in elliptical orbits. Parabolic reflectors focus incoming light to a single point, making them useful both as components of powerful telescopes and as tools for collecting solar energy. -

Generalized Conics with the Sharp Corners

Generalized conics with the sharp corners Aysylu Gabdulkhakova?1 and Walter G. Kropatsch1 Pattern Recognition and Image Processing group Technische Universit¨atWien Favoritenstrasse 9-11, Vienna, Austria faysylu,[email protected] Abstract. This paper analyses the properties of the generalized con- ics which are generated from N focal points with various weights. The weighting enables to obtain up to N corners located at the focal points. The corresponding level sets enable to capture the shape convexities and concavities. From the shape analysis perspective, the generalized conics enrich the variety of shapes that can be described or represented. Keywords: generalized conics · corner · shape representation 1 Introduction A generalized conic is a locus of points satisfying the equidistance property of the conic section (parabola, hyperbola or ellipse) that is extended to accept infinitely many focal points. Originally this subject raised an interest in the mathematical community. In particular, a multifocal ellipse (also called n-ellipse or polyellipse) plays a crucial role in solving Fermat-Torricelli [9, 10] and Weber [11] problems. The aim of the present paper is to explore the representational power of the generalized conics for shape analysis. Our previous research studied the ellipse and hyperbola, their properties and applicability to space tessellation [4], skeletonization [2, 4, 6] and smooth- ing [6]. The developed framework for efficient computation of the confocal elliptic and hyperbolic distance fields was extended to accept infinitely many weighted foci [3]. Also the geometric nature of the foci was reconsidered to accept not only the points, but also the shapes. This fact enables to apply various weighting schemes for objects, their parts and groups, and promote a hierarchical represen- tation. -

Bibliography of Map Projections

Bibliography of Map Projections Editors of first edition: John P. Snyder*and Harry Steward *Editor of revisions 1st edition: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1856, 1988 2nd edition: U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1856, 1997 Also two on-line editions installed at Ohio State University, 1994, 1996 under supervision of Eric John Miller and Duane F. Marble First printed edition by USGS, 1988 On-line editions at Ohio State University, 1994, 1996 Second printed edition, by USGS, 1997 This edition is printed using Word 6.0 for Windows 3.1 and using the following True Type fonts: Times New Roman, Century Gothic, Symbol, Cyrillic, and /HHGV%LW (XUR(DVW, (XUR1RUWK, (XUR:HVW, (XUR6RXWK, and ExtraChars 1. ii PREFACE [Although Harry Steward has not published by the Library of Congress in 1973 participated in the revisions of this bibliography, with a supplement in 1980 and an unpublished he contributed in a major manner to the first second supplement still in the process of edition and to this preface. Therefore, a assembly. Similar in significance are the near- separate preface has not been prepared for the annual listings of Bibliotheca Cartographica revisions. The numbers and some comments in (1957-1972) and its successor, Bibliographia the original preface have been updated. − JPS.] Cartographica (1974 to present), both published The discipline of cartography has a rich and in Germany but compiled from international complex history and a lengthy literature to contributions. accompany it. Cartographers have not only Additional valuable material has been made maps; they have written about them in derived from the published bibliography of the great detail. -

PHD THESIS – BOOKLET ISOPTIC CURVES and SURFACES Csima

PHD THESIS – BOOKLET ISOPTIC CURVES AND SURFACES Csima Géza Supervisor: Szirmai Jenő associate professor BUTE Mathematical Institute, Department of Geometry BUTE 2017 0.1 Introduction The topic of my thesis concerns isoptic curves and surfaces in Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries. This is the problem of generalizing the inscribed angle theorem. The question is quite simple: "What is the locus of points where a given object subtends a given angle?" It is well known that the locus of points in the plane from a segment subtends a given angle α (0 < α < π) is the union of two arcs except for π the endpoints with the segment as common chord. If this α is equal to 2 then we get the Thales circle. It is also known, that any point on the main circle of an ellipse has this property, that the tangent lines drawn from this point to the ellipse form a right angle. For the parabola, only the points on its directrix satisfy this property. Although the name "isoptic curve" was suggested by Taylor in 1884 ([62]), reference to former results can be found in [63]. In the obscure history of isoptic curves, we can find the names of la Hire (cycloids 1704) and Chasles (conics and epitrochoids 1837) among the contributors of the subject. A very interest- ing table of isoptic and orthoptic curves is introduced in [63], unfortunately without any exact reference of its source. However, recent works are available on the topic, which shows its timeliness. In [6] and [7], the Euclidean isoptic curves of closed strictly convex curves are studied using their support function. -

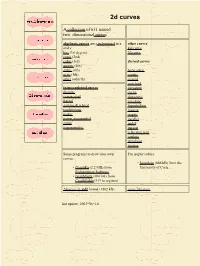

2Dcurves in .Pdf Format (1882 Kb) Curve Literature Last Update: 2003−06−14 Higher Last Updated: Lennard−Jones 2002−03−25 Potential

2d curves A collection of 631 named two−dimensional curves algebraic curves are a polynomial in x other curves and y kid curve line (1st degree) 3d curve conic (2nd) cubic (3rd) derived curves quartic (4th) sextic (6th) barycentric octic (8th) caustic other (otherth) cissoid conchoid transcendental curves curvature discrete cyclic exponential derivative fractal envelope gamma & related hyperbolism isochronous inverse power isoptic power exponential parallel spiral pedal trigonometric pursuit reflecting wall roulette strophoid tractrix Some programs to draw your own For isoptic cubics: curves: • Isoptikon (866 kB) from the • GraphEq (2.2 MB) from University of Crete Pedagoguery Software • GraphSight (696 kB) from Cradlefields ($19 to register) 2dcurves in .pdf format (1882 kB) curve literature last update: 2003−06−14 higher last updated: Lennard−Jones 2002−03−25 potential Atoms of an inert gas are in equilibrium with each other by means of an attracting van der Waals force and a repelling forces as result of overlapping electron orbits. These two forces together give the so−called Lennard−Jones potential, which is in fact a curve of thirteenth degree. backgrounds main last updated: 2002−11−16 history I collected curves when I was a young boy. Then, the papers rested in a box for decades. But when I found them, I picked the collection up again, some years spending much work on it, some years less. questions I have been thinking a long time about two questions: 1. what is the unity of curve? Stated differently as: when is a curve different from another one? 2. which equation belongs to a curve? 1. -

The Kinematic Analysis and Synthesis of Conic Constraint Pairs in Coplanar Motion

THE KINEMATIC ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS OF CONIC CONSTRAINT PAIRS IN COPLANAR MOTION By JACK WESLEY SPARKS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1970 To Willie Wesley Sparks and Perry Lynn Sparks ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author expresses his appreciation to Dr. Delbert Tesar for the suggestion and supervision of this dissertation. The author is indebted to C.A . Morrison and J.A. Samuels for the financial support provided by their research contracts with the Southern Service Company and the Office of Civil Defense. Appreciation is given to the following committee members for their guidance and supervision, Dr. D. Tesar Dr. R.B. Gaither Dr. J. Mahig Dr. J. M. Vance Dr. R. G. Selfridge. Finally, the author extends his deepest appreciation to Ills father and mother, to his family and to his wife, Cheri , for their financial support and encouragement. 1 1 r TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i i i LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF FIGURES viii ABSTRACT . x CHAPTER I GENERAL BACKGROUND . 1 Conic Sections. 2 .Analysis of the Coupler Curve Function for Conic Constraint Pairs ... 4 Analysis of the Coupler Curve Function for Burmsster Constraints. ... 4 Linkage Synthesis for Burmester nd Conic Constraint Pairs 5 Kinematic Synthesis for Burmester Constraints 6 Kinematic Synthesis for Conic Constraints 6 The Application of Coplanar Synthesis . , 7 II BURMESTER THEORY THE STATE OF THE ART. .... 15 Burmester Constraints Variables Vs. Parameters. 17 Burmester Theory The Study of Five Multiply Separated Positions in Coplanar Motion 13 Nine Precision Point Synthesis for Burmester Constraints ...