Hearing in the Starling (Sturn Us Vulgaris): Absolute Thresholds and Critical Ratios

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event. -

AMADOR BIRD TRACKS Monthly Newsletter of the Amador Bird Club June 2014 the Amador Bird Club Is a Group of People Who Share an Interest in Birds and Is Open to All

AMADOR BIRD TRACKS Monthly Newsletter of the Amador Bird Club June 2014 The Amador Bird Club is a group of people who share an interest in birds and is open to all. Happy Father’s Day! Pictured left is "Pale Male" with offspring, in residence at his 927 Fifth Avenue NYC apartment building nest, overlooking Central Park. Perhaps the most famous of all avian fathers, Pale Male’s story 3 (continued below) ... “home of the rare Amadorian Combo Parrot” Dates of bird club President’s Message The Amador Bird Club meeting will meetings this year: be held on: • June 13* Hi Everyone, hope you are enjoying the Friday, June 13, 2014 at 7:30 PM • July 11 warmer weather as I know that some of the • August 8 birds are "getting into the swing of things" and Place : Administration Building, • Sept. 12** producing for all of you breeders. This month Amador County Fairgrounds, • October 10 we will be having a very interesting and Plymouth informative presentation on breeding and • November 14 showing English budgies by Mary Ann Silva. I • December 12 Activity : Breeding and Showing am hoping that you all can attend as it will be English Budgies by Mary Ann (Xmas Party) your loss if you miss this night. Silva *Friday-the-13 th : drive carefully! We will be signing up for the Fair booth Refreshments: Persons with ** Semi-Annual attendance and manning so PLEASE mark it last names beginning with S-Z. Raffle on your calendar. The more volunteers the easier it is for EVERYONE. Set-up is always the Wed. -

Parakeet (Budgerigar)

PARAKEET (BUDGERIGAR) The budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) also known as common pet parakeet or shell parakeet and informally nicknamed the budgie, is a small, long-tailed, seed-eating parrot. Budgerigars are the only species in the Australian genus Melopsittacus, and are found wild throughout the drier parts of Australia where the species has survived harsh inland conditions for the last five million years. Budgerigars are naturally green and yellow with black, scalloped markings on the nape, back, and wings, but have been bred in captivity with colouring in blues, whites, yellows, greys, and even with small crests. Budgerigars are popular pets around the world due to their small size, low cost, and ability to mimic human speech. The species was first recorded in 1805, and today is the third most popular pet in the world, after the domesticated dog and cat. They are very active, playful birds, and they are incredibly intelligent. Some (but not all) budgies learn to talk, there are even budgies have a 100+ word vocabulary! Budgies can easily become finger tame while they are young with some diligent training, even if they were not hand fed as babies. Many owners of fully tamed budgies will swear that their budgie thinks it's a human! Even if a budgie is not tamed, they still make enjoyable pets. Their antics and singing will brighten up any room in your home. And budgies who are not finger tame still can become friendly towards you, and even still learn to talk. Name Many people know them as "parakeets," but their real name is "budgerigar". -

The English Budgerigarvs

The English All Natural Supplement for Exotic Birds .n. BEAUlY FERTILIlY\ Budgerigar betaearotene vitamins calcium minerals mucoproteins Algae-Feast Spirulina is used by avian experts at by Buddy Walker zoo's and exotic bird breeding centers worldwide. Im Phoenix, Arizona proves fertility in scientific tests. Low in sodium, rich in amino acids. Very concentrated, at tittle goes a long way. A BitofHistory For Cockatiels, Parrots, Softbills, Canaries and Finches. The Budgerigar was unknown •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• outside its native land until Captain Yes, Send me Algae-Feast Spirulina powder now! James Cook discovered Australia D during 1770. It was not until 1794, FREE UPS delivery in Continental USA however, that European naturalist $36.00 -- One Pound Jar IAsk about Wholesale and Bulk I John Gould first reported seeing $83.00 __ Four Pound Jar large flocks of small green parrots Payment amountS:.....- by: 0 check 0 MC 0 Visa dUring his venture to Austrailia. The grass parakeet was a favorite credit card # expo date, _ food of the Aborigines. In fact, the Name on card Phone _ Aborigines call this bird" Betcherry Delivery address, _ gah" (good food), hence the name City, State, Zip _ "Budgerigar:' The Budgerigar has Mail to: Algae-Feast, P.O. Box 719-A, Calipatria, CA 92233 also been termed with several other FAX 619 348-2895 TEL 619 348-2685 names such as shell parrot, grass parakeet and parakeet. Budgerigars were first imported to England during 1840 and soon after wards were imported to the United States. Import dealers imported sev eral hundred thousands of Budgeri gars until 1894 when the Australian government placed a ban on the exportation ofthese birds. -

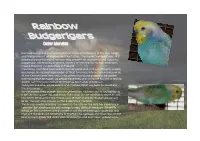

Rainbow Budgies Are a Combination of Several Mutations in the Blue Range and Therefore Not an Independent Mutation

Rainbow budgies are a combination of several mutations in the blue range and therefore not an independent mutation. The name “rainbow” was first used by Keston Foreign Bird Farm who create this wonderful and colourful budgerigar. The Boosey brothers owners of the Keston Foreign Bird Farm create this bird for petshops in England. Previously such bird have been bred in England and on the Continent, usually by change. No respected breeder at that time was interested in these birds. At the Keston farm they only used yellow-faced and goldenfaced opaline whitewing blue an cobalt. As yellow-face they practiced the Mutant 2 and as golden face they used what we know as Australian yellowface. Today we see also visual violets and mauves. What we have to avoid are the grey birds. On the shows they accept also the yellowface Mutant 1 but in my opinion is it better not to use this mutation. The colour of the rainbow is more attrac- tive when we practice the Yellow face Mutant 2 and Australian yellowface birds. The last ones known as the Goldenface rainbow. The problem with breeding rainbow’s is the size of the bird. My experience tells me that finding good whitewings is very difficult because the white- wings on the continent are different from the whitewings in Australia and that are the birds we needed to breed the real rainbow. For that reason the Keston Farm imported Australian whitewings and Australian yellowfaces. YELLOWFACE GROUP YELLOWFACE (MUTANT 1) All varieties in the blue series The standard will be as for all the different varieties in the blue series including grey and should conform in every respect except in the follo- wing details: General body co- as the corresponding white face variety. -

Of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16

ONE What are the Parrots and Where Did They Come From? The Evolutionary History of the Parrots CONTENTS The Marvelous Diversity of Parrots 3 Other Major Groups of Parrots 16 Reconstructing Evolutionary History 5 Box 1. Ancient DNA Reveals the Evolutionary Relationships of the Fossils, Bones, and Genes 5 Carolina Parakeet 19 The Evolution of Parrots 8 How and When the Parrots Diversified 25 Parrots’ Ancestors and Closest Some Parrot Enigmas 29 Relatives 8 What Is a Budgerigar? 29 The Most Primitive Parrot 13 How Have Different Body Shapes Evolved in The Most Basal Clade of Parrots 15 the Parrots? 32 THE MARVELOUS DIVERSITY OF PARROTS The parrots are one of the most marvelously diverse groups of birds in the world. They daz- zle the beholder with every color in the rainbow (figure 3). They range in size from tiny pygmy parrots weighing just over 10 grams to giant macaws weighing over a kilogram. They consume a wide variety of foods, including fruit, seeds, nectar, insects, and in a few cases, flesh. They produce large repertoires of sounds, ranging from grating squawks to cheery whistles to, more rarely, long melodious songs. They inhabit a broad array of habitats, from lowland tropical rainforest to high-altitude tundra to desert scrubland to urban jungle. They range over every continent but Antarctica, and inhabit some of the most far-flung islands on the planet. They include some of the most endangered species on Earth and some of the most rapidly expanding and aggressive invaders of human-altered landscapes. Increasingly, research into the lives of wild parrots is revealing that they exhibit a corresponding variety of mating systems, communication signals, social organizations, mental capacities, and life spans. -

Autosomal Colour Mosaics in the Budgerigar

AUTOSOMAL COLOUP~ MOSAICS IN TI-IE BUDGEP~IGAI%. BY F. A. E. CI~EW ~D I¢0WENA LAMY. (I~stitute of Aq~i,ma~ Genetics, Unive~'sity of E(~inbuq:qh.) (With Plate X and One Text-figure.) BUDeE~IGA~ liLerature cmltains many references to "bieolours." The term "bicoloured," strictly used, is applied only to what the fanciers call a "half-sider" : a bird. with the plumage of one half of the body (one side from head to tail inclusive) of a colour appropriate to one variety, whilst the other ]lalf (side) is of a colour characteristic of another variety. But it is often used more loosely to describe any bird with two different varietal colours in its plumage, the actual regional distribution of these not being taken into account. The following list, which cannot be accepted as exhaustive, includes seven cases recorded in the Bu@e'ripa~" BulZetin, two eases described in De~" Wdle~zsil,tid~, and eight concerning which we have had correspondence with their owners. Two specimens have been lent to us ~or examination, but in no case has a eytologicM study been made : the bird is too valuable when alive, and useless for cytological purposes when dead. In all the popular books on the budgerigar to which we have had access it is stated that the bicoloured bird has its origin in an egg with two germs. This, presumably, is a reference to the explanations of gynandromorphism in the insect suggested by Boveri (1888), Morgan (1905), and Doncaster (1914). It will be remembered that Boveri ac- counted for this phenomenon by suggesting that the sperm enters au egg which has already begun its first division, and fuses with one of the resulting daughter nucl'ei. -

Chromosome-Level Assembly Reveals Extensive Rearrangement In

Aberystwyth University Chromosome-level assembly reveals extensive rearrangement in sakar falcon and budgerigar, but not ostrich, genomes O'Connor, Rebecca E.; Farré, Marta; Joseph, Sunitha; Damas, Joana; Kiazim, Lucas ; Jennings, Rebecca; Bennett, Sophie; Slack, Eden A.; Allanson, Emily; Larkin, Denis M.; Griffin, Darren K. Published in: Genome Biology DOI: 10.1186/s13059-018-1550-x Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): O'Connor, R. E., Farré, M., Joseph, S., Damas, J., Kiazim, L., Jennings, R., Bennett, S., Slack, E. A., Allanson, E., Larkin, D. M., & Griffin, D. K. (2018). Chromosome-level assembly reveals extensive rearrangement in sakar falcon and budgerigar, but not ostrich, genomes. Genome Biology, 19, [171]. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059- 018-1550-x Document License CC BY General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 04. -

First Report on the Rose-Ringed Parakeet(Psittacula Krameri) in Venezuela and Preliminary Observations on Its Behavior

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 10: 115–117, 1999 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society FIRST REPORT ON THE ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET(PSITTACULA KRAMERI) IN VENEZUELA AND PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS ON ITS BEHAVIOR Javier Colvée Nebot Sociedad Conservacionista Audubon de Venezuela, Calle Veracruz, Edif Matisco, Las Mercedes, Caracas, Venezuela. Key words: Psittaciformes, Psittacula krameri, possible subspecies, behavior, native species. In May 1996, several Rose-ringed Parakeet keet has been described from China, India (Psittacula krameri) individuals were observed and Burma to Africa (Fry et al. 1988, Forshaw in Parque del Este, a large park (85 ha) situ- 1989). It has also been introduced and ated within the eastern Caracas City limits, observed in a number of countries: Mauritius, Venezuela (10°30’24”N, 66°55’39”W). The Zanzíbar, Egypt, Oman, Republic of the present report corresponds apparently to the Yemen, Kuwait, Iraq, Iran, Hong Kong and first record of the presence of this species in Macao, Singapore, Cape Green Islands, feral populations in Venezuela and for main- Afghanistan, Kenya, Hawaiian Islands and land South America as a whole. continental USA, Great Britain, Adaman The introduction of exotic psittacids in Islands, Spain, Germany (Forshaw 1989), natural areas by accidental or intentional Netherlands (Long 1981), Belgium (Perrins means occurs quite frequently (Long 1981). 1990) and Curaçao (Voous 1983, 1985). In Venezuela, two introduced especies of Almost all observations noted in the psittacids: Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) present report were conducted in the large and Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) have densely forested areas of the Parque del Este, been reported in feral populations (Badillo & and some nearby forested patches (less than 5 Ulloa 1987, 1994). -

Neuromuscular Control and Kinematics of Intermittent Flight in the European Starling (Sturnus Vulgaris)

The Journal of Experimental Biology 198, 1259–1273 (1995) 1259 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1995 NEUROMUSCULAR CONTROL AND KINEMATICS OF INTERMITTENT FLIGHT IN THE EUROPEAN STARLING (STURNUS VULGARIS) BRET W. TOBALSKE Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812, USA Accepted 27 February 1995 Summary Electromyographic (EMG) and kinematic data were scapulohumeralis caudalis occasionally showed activity collected from European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) flying during bounds, which may reflect its role as a humeral at a range of speeds from 8 to 18 m s21 in a variable-speed retractor. The frequency and duration of non-flapping windtunnel. Their flight at all speeds consisted of alternating intervals in starlings were less during EMG experiments flapping and non-flapping phases. Wing postures during than during non-implanted flights. non-flapping phases included glides, partial-bounds and During flapping phases, relative intensity and duration bounds. Glides were performed proportionally more often of EMG signal and wingbeat frequency increased with within each speed and were longer in duration than either flight speed, whereas flapping or non-flapping cycle of the other two non-flapping postures, but the percentage duration, the percentage of a cycle spent flapping and the of bounds increased markedly with increasing flight speed. number of wingbeats in a cycle were all greatest at 8 m s21. The shift from flap-gliding at slow speeds towards flap- Wingbeat amplitude was smaller at intermediate speeds, bounding at fast speeds was consistent with reducing mean but differences among speeds were not significant. These power output relative to continuous flapping. -

Pet Bird Oncology

PET BIRD ONCOLOGY Drury Reavill Zoo/Exotic Pathology Service 2825 KOVR Drive West Sacramento, CA 95605 (Modified and up‐dated, and used with permission from AAV Proceedings 2001) Although neoplastic diseases occur with some frequency in the commonly kept pet birds, published information regarding prognosis and therapy of specific neoplasms is limited. Each case report or study that provides this information, helps us to improve the level of care we can offer our companion avian pets. This review will cover some basic information about select tumour types with attempted therapies and will reference the more recent reports in the avian literature. It is not intended to be all encompassing. For more information, there are extensive published reviews of the reported avian tumours (Leach 1992; Reece 1992; Reavill,2004). Table 1 provides a summary of therapies reported in pet birds. A survey of the tumours diagnosed at our service, Zoo Excotic Pathology Service (ZEPS), will be discussed. SELECTED PET BIRD TUMOURS Haemangiomas and Haemangiosarcomas Haemangiomas are benign tumours of vascular endothelium. The malignant version is haemangiosarcoma, also known as malignant haemangioendothelioma or angiosarcoma. Haemangiomas are more commonly reported in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) than in other birds, and usually occur in the skin or spleen (Leach 1992; Reece 1992). Splenic and cutaneous haemangiomas have also been reported in African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) and an Indian ring‐necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri) (Leach, 1992). Of the haemangiomas we’ve seen (n=19), the majority were removed from the skin (feet, inguinal region, cloaca, side of neck, and wing); one was found in the spleen.