Chapter 25: Oncology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who, How and What of Pathology of Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Editorial Page 1 of 11 Who, how and what of pathology of soft tissue sarcoma Salvatore Lorenzo Renne Anatomic Pathology Unit, Humanitas Research Hospital, Humanitas University, Rozzano, MI 20089, Italy Correspondence to: Salvatore Lorenzo Renne. Adjunct Teaching Professor, Anatomic Pathology Unit, Humanitas Research Hospital, Humanitas University, Via Manzoni 56, Rozzano, MI 20089, Italy. Email: [email protected]. Submitted Aug 06, 2018. Accepted for publication Aug 23, 2018. doi: 10.21037/cco.2018.10.09 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cco.2018.10.09 Introduction to soft tissue sarcoma (STS) adipocytes (lipoma, spindle cells lipoma, hibernoma, well- pathology differentiated liposarcoma (LPS), myxoid LPS, etc.). One chapter is dedicated to specific entities “of uncertain STS is a generic term that refers to a heterogeneous group differentiation” that are well-characterized entities that do of rare neoplastic diseases. The aim of this review is to not readily resemble any normal mesenchymal cells (as the discuss the role of pathology in the multidisciplinary Ewing sarcoma or the synovial sarcoma—a clear misnomer). management of STS patients. This will be done: (I) The last chapter is dedicated to those sarcomas that do illustrating the framework for the current classification; (II) not follow in any of the previously listed diagnosis and are examining the characteristics that allows an expert diagnosis; therefore called “undifferentiated/unclassified sarcomas” (III) describing the role of the sarcoma pathologist -

Complete Case of a Rare but Benign Soft Tissue Tumor

Hindawi Case Reports in Orthopedics Volume 2019, Article ID 6840693, 5 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6840693 Case Report Hibernoma of the Upper Extremity: Complete Case of a Rare but Benign Soft Tissue Tumor Thomas Reichel ,1 Kilian Rueckl,1 Annabel Fenwick,1,2 Niklas Vogt,3 Maximilian Rudert,1 and Piet Plumhoff1 1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Koenig-Ludwig-Haus, University of Wuerzburg, Brettreichstraße 11, 97074 Wuerzburg, Germany 2Department of Trauma Surgery, Klinikum Augsburg, 86156 Augsburg, Germany 3Department of Pathology, University of Wuerzburg, 97080 Wuerzburg, Germany Correspondence should be addressed to Thomas Reichel; [email protected] Received 26 February 2019; Accepted 14 April 2019; Published 21 May 2019 Academic Editor: Elke R. Ahlmann Copyright © 2019 Thomas Reichel et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Hibernoma is a rare benign lipomatous tumor showing differentiation of brown fatty tissue. To the author’s best knowledge, there is no known case of malignant transformation or metastasis. Due to their slow, noninfiltrating growth hibernomas are often an incidental finding in the third or fourth decade of life. The vast majority are located in the thigh, neck, and periscapular region. A diagnostic workup includes ultrasound and contrast-enhanced MRI. Differential diagnosis is benign lipoma, well- differentiated liposarcoma, and rhabdomyoma. An incisional biopsy followed by marginal resection of the tumor is the standard of care, and recurrence after complete resection is not reported. The current paper presents diagnostic and intraoperative findings of a hibernoma of the upper arm and reviews similar reports in the current literature. -

Pleomorphic Adenoma of Buccal Mucosa: a Rare Case Report

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 16, Issue 3 Ver. XI (March. 2017), PP 75-78 www.iosrjournals.org Pleomorphic Adenoma of Buccal Mucosa: A Rare Case Report Ashwini Jangamashetti, BDS1, Siddesh Shenoy, MDS2, R.Krishna Kumar MDS3, Amol Jeur, MS4 1Post Graduate Student, Department Of Oral Medicine And Radiology, MARDC,Pune 2Reader, Department of oral Medicine and radiology, M.A Rangoonwala Dental College and Research Center, Pune (MARDC), 3Professor and HOD, Department of oral Medicine and Radiology, MARDC, Pune 4Assistant Professor in Department of General surgery, Krishna Medical College of KIMS Deemed University , Abstract: Pleomorphic adenoma is a benign tumor of the salivary gland that consists of a combination of epithelial and mesenchymal elements1. About 90% of these tumors occur in the parotid gland and 10% in the minor salivary glands2. Among intra oral pleomorphic adenomas buccal vestibule is among the rarest sites3. A case of pleomorphic adenoma of minor salivary glands in the buccal vestibule in a 36 year-old female is discussed4. It includes review of literature, clinical features, histopathology, radiological findings and treatment of the tumor, with emphasis on diagnosis4. The mass was removed by wide local excision with adequate margins5. Keywords: minor salivary gland, pleomorphic adenoma, tumor, parotid gland, vestibule, mesenchymal elements. I. Introduction Pleomorphic adenoma (PA) is defined by World Health Organization in 1972 as a circumscribed tumor characterized by its pleomorphic or mixed appearance clearly recognizable epithelial tissue being intermingled with tissue of mucoid, myxoid and chondroid appearance2. Among all salivary gland tumors, pleomorphic adenoma is the most frequently encountered lesion accounting for approximately 60% of all salivary gland neoplasms3. -

Soft Tissue Cytopathology: a Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD

4/1/2020 Soft Tissue Cytopathology: A Practical Approach Liron Pantanowitz, MD Department of Pathology University of Pittsburgh Medical Center [email protected] What does the clinician want to know? • Is the lesion of mesenchymal origin or not? • Is it begin or malignant? • If it is malignant: – Is it a small round cell tumor & if so what type? – Is this soft tissue neoplasm of low or high‐grade? Practical diagnostic categories used in soft tissue cytopathology 1 4/1/2020 Practical approach to interpret FNA of soft tissue lesions involves: 1. Predominant cell type present 2. Background pattern recognition Cell Type Stroma • Lipomatous • Myxoid • Spindle cells • Other • Giant cells • Round cells • Epithelioid • Pleomorphic Lipomatous Spindle cell Small round cell Fibrolipoma Leiomyosarcoma Ewing sarcoma Myxoid Epithelioid Pleomorphic Myxoid sarcoma Clear cell sarcoma Pleomorphic sarcoma 2 4/1/2020 CASE #1 • 45yr Man • Thigh mass (fatty) • CNB with TP (DQ stain) DQ Mag 20x ALT –Floret cells 3 4/1/2020 Adipocytic Lesions • Lipoma ‐ most common soft tissue neoplasm • Liposarcoma ‐ most common adult soft tissue sarcoma • Benign features: – Large, univacuolated adipocytes of uniform size – Small, bland nuclei without atypia • Malignant features: – Lipoblasts, pleomorphic giant cells or round cells – Vascular myxoid stroma • Pitfalls: Lipophages & pseudo‐lipoblasts • Fat easily destroyed (oil globules) & lost with preparation Lipoma & Variants . Angiolipoma (prominent vessels) . Myolipoma (smooth muscle) . Angiomyolipoma (vessels + smooth muscle) . Myelolipoma (hematopoietic elements) . Chondroid lipoma (chondromyxoid matrix) . Spindle cell lipoma (CD34+ spindle cells) . Pleomorphic lipoma . Intramuscular lipoma Lipoma 4 4/1/2020 Angiolipoma Myelolipoma Lipoblasts • Typically multivacuolated • Can be monovacuolated • Hyperchromatic nuclei • Irregular (scalloped) nuclei • Nucleoli not typically seen 5 4/1/2020 WD liposarcoma Layfield et al. -

The Use of High Tumescent Power Assisted Liposuction in the Treatment of Madelung’S Collar

Letter to the Editor The use of high tumescent power assisted liposuction in the treatment of Madelung’s collar Henryk Witmanowski1,2, Łukasz Banasiak1, Grzegorz Kierzynka1, Jarosław Markowicz1, Jerzy Kolasiński1, Katarzyna Błochowiak3, Paweł Szychta1,4 1Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Medical College in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun, Poland 2Department of Physiology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 3Department of the Oral Surgery, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland 4Department of Oncological Surgery and Breast Diseases, Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital-Research Institute, Lodz, Poland Adv Dermatol Allergol 2017; XXXIV (4): 366–371 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2017.69319 Mild symmetrical lipomatosis (plural symmetrical The disease most commonly takes a proximal form lipomatosis, multiple symmetric lipomatosis – MSL), which takes the following areas of the body with the fol- also known as Madelung’s disease or Launois-Bensaude lowing frequency: the genial area 92.3%, cervical region syndrome is a rare disease of unknown etiology, first de- 67.7%, shoulder region 54.8%, abdominal 45.2%, chest scribed by Brodie in 1846, Madelung in 1888, and Launois 41.9%, thigh and pelvic rim 32.3% [11, 12]. The periph- with Bensaude in 1898 [1–3]. eral type mainly locates on both sides at the level of the Madelung’s disease incidence is 1 : 250000 [4]. Mul- hands, feet and knees, this is definitely a rarer form of tiple symmetric lipomatosis occurs mainly in the inhabit- the disease. The mixed form is described very rarely. The ants of the Mediterranean area and Eastern Europe, in specified central type is also engaged primarily around males (male to female ratio is 20 : 1), aged 30–70 years, the lower torso, and intermediate parts of the legs. -

Thyroid Follicular Adenoma: Benign Or Malignant?

Volume 4 Number 3 Medical Journal of the ['ayiz1369 Islamic Repuhlit of Imn Rabiolawwal141 I F:llll990 THYROID FOLLICULAR ADENOMA: BENIGN OR MALIGNANT? HOSSEIN GHARIB, M.D. From fhe Division of Endocrillology and !lIlernal Medicine, Mayo Clinic and Mayo FOll1uiafion, Rochester, MillllCSOla, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Four patients are described in whom a follicular carcinoma developed following thyroidectomy for a benign follicular neoplasm. It is possible that the initial thyroid neoplasm was a well- differentiated follicular carcinoma which was microscopically indistinguishable from a benign adenoma. Realizing this pathologic pitfall in thyroid diagnosis, the need for meticulous examination of the pathologic specimen is emphasized. Long- term postop erative reassessment is recommended. MIIRI, Vol. 4, No.3, 173-176, 1990 INTRODUCTION CASE REPORTS Follicular adenoma is the most common type of Case I cellular thyroid adenomas. 1 There is considerable de A 49-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of bate whether follicular adenoma of the thyroid, a metastatic thyroid carcinoma. She was in good health benign neoplasm, is a precancerous lesion which occa until six months earlier when she complained of ins om- sionally may be mistaken for a carcinoma2.30n the nia and nervousness. Two months before admission a other hand, several published reports indicate that a routine chest x-ray revealed metastatic nodules in both follicular adenoma which appears benign by conven lungs. Extensive laboratory tests and radiographic tional histologic criteria, may demonstrate malignant studies were negative. A diagnostic left thoracotomy behavior."·() showed ,dow grade thyroid cancep. and she was refer This report describes four patients whose thyroid red for further examination. -

Comprehensive Assessment of TERT Mrna Expression Across a Large Cohort of Benign and Malignant Thyroid Tumours

cancers Article Comprehensive Assessment of TERT mRNA Expression across a Large Cohort of Benign and Malignant Thyroid Tumours Ana Pestana 1,2,3, Rui Batista 1,2,3, Ricardo Celestino 1,2,3,4 , Sule Canberk 1,2,5, Manuel Sobrinho-Simões 1,2,3,6 and Paula Soares 1,2,3,7,* 1 Institute of Molecular Pathology and Immunology of the University of Porto (Ipatimup), 4200-135 Porto, Portugal; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (R.C.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (M.S.-S.) 2 i3S-Instituto de Investigação e Inovação em Saúde, Universidade do Porto, 4200-135 Porto, Portugal 3 Medical Faculty of University of Porto (FMUP), 4200-139 Porto, Portugal 4 School of Allied Health Technologies, Polytechnic of Porto, 4200-072 Porto, Portugal 5 Abel Salazar Biomedical Sciences Institute (ICBAS), University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 6 Department of Pathology, Centro Hospitalar São João, 4200-139 Porto, Portugal 7 Department of Pathology, Medical Faculty of the University of Porto, 4200-139 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-220-408-800 Received: 10 June 2020; Accepted: 6 July 2020; Published: 9 July 2020 Abstract: The presence of TERT promoter (TERTp) mutations in thyroid cancer have been associated with worse prognosis features, whereas the extent and meaning of the expression and activation of TERT in thyroid tumours is still largely unknown. We analysed frozen samples from a series of benign and malignant thyroid tumours, displaying non-aggressive features and low mutational burden in order to evaluate the presence of TERTp mutations and TERT mRNA expression in these settings. -

Adenomatoid Tumor of the Skin: Differential Diagnosis of an Umbilical Erythematous Plaque

Title: Adenomatoid tumor of the skin: differential diagnosis of an umbilical erythematous plaque Keywords: Adenomatoid tumor, skin, umbilicus Short title: Adenomatoid tumor of the skin Authors: Ingrid Ferreira1, Olivier De Lathouwer2, Hugues Fierens3, Anne Theunis1, Josette André1, Nicolas de Saint Aubain3 1Dermatopathology laboratory, Department of Dermatology, Saint-Pierre University Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium. 2Department of Plastic surgery, Centre Hospitalier Interrégional Edith Cavell, Waterloo, Belgium. 3Department of Dermatology, Saint-Jean Hospital, Brussels, Belgium. 4Department of Pathology, Jules Bordet Institute, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium. Acknowledgements: None Corresponding author: Ingrid Ferreira This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1111/cup.13872 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Abstract Adenomatoid tumors are benign tumors of mesothelial origin that are usually encountered in the genital tract. Although they have been observed in other organs, the skin appears to be a very rare location with only one case reported in the literature to our knowledge. We report a second case of an adenomatoid tumor, arising in the umbilicus of a 44-year-old woman. The patient presented with an 8 months old erythematous and firm plaque under the umbilicus. A skin biopsy showed numerous microcystic spaces dissecting a fibrous stroma and being lined by flattened to cuboidal cells with focal intraluminal papillary formation. This poorly known diagnosis constitutes a diagnostic pitfall for dermatopathologists and dermatologists, and could be misdiagnosed as other benign or malignant entities. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE IDENTIFICATION OF BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS IN ZOOARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSEMBLAGES VOLUME 1 (1 OF 2) J. E. WOODING PhD UNIVERSITY OF BRADFORD 2010 THE IDENTIFICATION OF BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS IN ZOOARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSEMBLAGES Working towards differential diagnostic criteria Volume 1 (1 of 2) Jeanette Eve WOODING Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Life Sciences Division of Archaeological, Geographical and Environmental Sciences University of Bradford 2010 Jeanette Eve WOODING The identification of bovine tuberculosis in zooarchaeological assemblages. Working towards differential diagnostic criteria. Keywords: Palaeopathology, zooarchaeology, human osteoarchaeology, zoonosis, Iron Age, Viking Age, Iceland, Orkney, England ABSTRACT The study of human palaeopathology has developed considerably in the last three decades resulting in a structured and standardised framework of practice, based upon skeletal lesion patterning and differential diagnosis. By comparison, disarticulated zooarchaeological assemblages have precluded the observation of lesion distributions, resulting in a dearth of information regarding differential diagnosis and a lack of standard palaeopathological recording methods. Therefore, zoopalaeopathology has been restricted to the analysis of localised pathologies and ‘interesting specimens’. Under present circumstances, researchers can draw little confidence that the routine recording of palaeopathological lesions, their description or differential diagnosis will ever form a standard part of zooarchaeological analysis. This has impeded the understanding of animal disease in past society and, in particular, has restricted the study of systemic disease. -

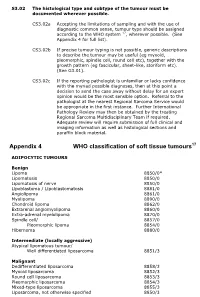

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Epssg NRSTS 2005

EpSSG NRSTS 2005 a protocol for Localized Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas VERSION 1.1 SEPTEMBER 2009 EpSSG NRSTS 2005 protocol Version 1.1 Contents 1. Administrative organisation p. 3 1.1 Protocol sponsor p. 3 1.2 Protocol coordination p. 3 1.3 EpSSG and NRSTS 2005 structure p. 4 2. Abbreviations p.10 3. Summary p.11 3.1. Objectives p.12 3.2. Patients eligibility p.12 3.3. Patients stratification p.13 3.4. Pathology and Biology p.13 3.5. Statistical consideration p.13 3.6. Organisation of the study p.14 3.7. Datamanagement and analysis p.14 3.8. Ethical consideration p.14 4. Background p.16 4.1. References p.20 5. Study structure p.22 6. Patient eligibility p.22 7. Pre-treatment investigation p.23 7.1. Histological diagnosis p.23 7.2. Clinical assessment p.23 7.3. Laboratory investigations p.23 7.4. Radiological investigations p.24 7.5. Tumour measurements p.25 7.6. Lung lesions p.25 8. Staging system p.26 8.1. References p.26 9. Surgical guidelines p.27 9.1. Definitions p.27 9.2. Biopsy p.28 9.3. Primary resection p.29 9.4. Primary re-operation p.30 9.5. Secondary re-operation p.30 9.6. Reconstructive surgery and local control p.31 9.7. Lymph nodes p.31 9.8. Specific sites p.32 9.9. Surgery for relapse p.34 9.10. Marker clips p.34 9.11. Histology p.34 9.12. References p.34 10.