06 Physical Examination.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy Did you see any birds during your nature observation? In Washington State, we observe birds more than any other type of wild vertebrate (animals with a backbone). Think about it. Most people see or hear a wild bird on most days of their life. That can not be said of wild mammals, reptiles, or fish. Once you start noticing birds, most people want to be able to identify what birds they are observing. Often, one of the first things a person notices about a bird is their colors and patterns. Those are called field marks. When you are using field marks, it helps if you know a little bird anatomy. Ornithologists (people who study birds) talk about parts of a bird by dividing its body into regions. The main areas are beak (or bill), head, back, throat, breast, wings, tail, and legs. Many of these regions are divided still further. Purpose: At the end of this lesson I can say with confidence . 1) I can create and use a diagram of a bird’s feathers. Directions: 1) Click on the link below to go to TheCornellLab Bird Academy to learn All About Bird Anatomy. a) https://academy.allaboutbirds.org/features/birdanatomy/ i) Click the -GO!- button to enter the interactive learning tool. ii) Turn each system on or off by using the color-coded boxes. iii) Learn about the individual parts in a system by clicking on the box. The part will be highlighted on the bird diagram. iv) Click on the highlighted section of the bird diagram to learn the function or description of each part and how to pronounce its name. -

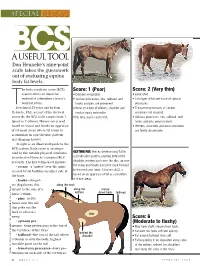

Horses Are Scored Hooks and Pins Are Prominent

SPECIAL REPORT BCS A USEFUL TOOL Don Henneke’s nine-point scale takes the guesswork out of evaluating equine body fat levels. he body condition score (BCS) Score: 1 (Poor) Score: 2 (Very thin) system offers an objective • Extreme emaciation. • Emaciated. method of estimating a horse’s • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and • Thin layer of fat over base of spinous body fat levels. hooks and pins are prominent. processes. TDeveloped 25 years ago by Don • Bone structure of withers, shoulder and • Transverse processes of lumbar Henneke, PhD, as part of his doctoral neck is easily noticeable. vertebrae feel rounded. research, the BCS scale ranges from 1 • No fatty tissue can be felt. • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and (poor) to 9 (obese). Horses are scored hooks and pins are prominent. based on visual and hands-on appraisal • Withers, shoulders and neck structures of six body areas where fat tends to are faintly discernable. accumulate in a predictable pattern (see diagram below). At right is an illustrated guide to the BCS system. Each score is accompa- nied by the notable physical attributes GETTING FAT: Horses develop body fat in described in Henneke’s original BCS a predictable pattern, starting behind the research. The key terms used include: shoulder, moving back over the ribs, up over • crease---a “gutter” over the spine the rump and finally along the back forward created by fat buildup on either side of to the neck and head. A horse’s BCS is the bone. based on an appraisal of fat accumulation • hooks---the pel- in these areas. -

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014

INTRODUCED CORELLA ISSUES PAPER April 2014 City of Bunbury Page 1 of 35 Disclaimer: This document has been published by the City of Bunbury. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith and on the basis that the City of Bunbury, its employees and agents are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which may occur as a result of action taken or not taken, as the case may be, in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to herein. Information pertaining to this document may be subject to change, and should be checked against any modifications or amendments subsequent to the document’s publication. Acknowledgements: The City of Bunbury thanks the following stakeholders for providing information during the drafting of this paper: Mark Blythman – Department of Parks and Wildlife Clinton Charles – Feral Pest Services Pia Courtis – Department of Parks and Wildlife (WA - Bunbury Branch Office) Carl Grondal – City of Mandurah Grant MacKinnon – City of Swan Peter Mawson – Perth Zoo Samantha Pickering – Shire of Harvey Andrew Reeves – Department of Agriculture and Food (WA) Bill Rutherford – Ornithological Technical Services Publication Details: Published by the City of Bunbury. Copyright © the City of Bunbury 2013. Recommended Citation: Strang, M., Bennett, T., Deeley, B., Barton, J. and Klunzinger, M. (2014). Introduced Corella Issues Paper. City of Bunbury: Bunbury, Western Australia. Edition Details: Title: Introduced Corella Issues Paper Production Date: 15 July 2013 Author: M. Strang, T. Bennett Editor: M. Strang, B. Deeley Modifications List: Version Date Amendments Prepared by Final Draft 15 July 2013 M. -

Dwi Astuti Zoological Division, R.C

Phylogenetic relationships of cockatoos (Aves: Psittaciformes) based on DNA sequences of the seventh intron of nuclear β-fibrinogen gene Dwi Astuti Zoological Division, R.C. for Biology - Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Cibinong Science Centre Indonesia [email protected] O Cockatoos are belonged to Cacatuinae (Forshaw, 1989) order : Psittaciformes, Cockatoo Distribution family : Psittacidae (Forshaw, 1989) Calopsittacini Chalyptorhynchini Cacatuini Cacatuidae (del Hoyo,1998) Nymphicus subfamily: Cacatuinae Probosciger Calyptorhynchus Challocephalon Eolophus Cacatua tribes : Calopsittacini Chalyptorhynchini Cacatuini E. roseicapillus Probosciger N. hollandicus P. aterrimus C. baudinii C. fimbriatum C. sulphurea O In the world, there are six extant genera C. latirostris C.galerita Eolophus C. lathami C. alba Cacatua consisting of 21 cockatoo species C. banksii Nymphicus C. moluccensis leadbeateri C. funereus C. goffini Calyptorhynchus O Some previous authors have made grouping C. magnificus C. sanguinea Calyptorhynchus Callocephalon C. leadbeateri and evolutionary relationships of cockatoos C. ophthalmia Brown & Toft (1999) based on morphological characters, isozyme, C. haematuropygia and mitochondrial DNA. However, their MATERIALS AND METHODS relationships are still controversial, especially Phylogeny based on different characters concerning the position of Nymphycus Cacatua leadbeateri Blood samples from each individual of 15 species, Biochemical 6 genera, and 3 tribes of cockatoos hollandicus. Since the nuclear β-fibrinogen (Adams et -

Cockatiels Free

FREE COCKATIELS PDF Thomas Haupt,Julie Rach Mancini | 96 pages | 05 Aug 2008 | Barron's Educational Series Inc.,U.S. | 9780764138966 | English | Hauppauge, United States How to Take Care of a Cockatiel (with Pictures) - wikiHow A cockatiel is a popular choice for a pet bird. It is a small parrot with a variety of color patterns and a head crest. They are attractive as well as friendly. They are capable of mimicking speech, although they can be difficult to understand. These birds are good at whistling and you can teach them to sing along to tunes. Life Expectancy: 15 to 20 years with proper care, and sometimes as Cockatiels as 30 years though this is rare. In their native Australia, cockatiels are Cockatiels quarrions or weiros. They primarily live in the Cockatiels, a region of the northern part of the Cockatiels. Discovered inthey are the smallest members of the cockatoo family. They exhibit many of the Cockatiels features and habits as the larger Cockatiels. In the wild, they live in large flocks. Cockatiels became Cockatiels as pets during the s. They are easy to breed in captivity and their docile, friendly personalities make them a natural fit for Cockatiels life. These birds can Cockatiels longer be trapped and exported from Australia. These little birds are gentle, affectionate, and often like to be petted and held. Cockatiels are not necessarily fond of cuddling. They simply want to be near you and will be very happy to see you. Cockatiels are generally friendly; however, an untamed bird might nip. You can prevent bad Cockatiels at an early age Cockatiels ignoring bad behavior as these birds aim to please. -

A Case Study of the Endangered Carnaby's Cockatoo

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Nature ConservationNature 9: 19–43 conservation (2014) on agricultural land: a case study of the endangered... 19 doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.9.8385 CONSERVATION IN PRACTICE http://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation Nature conservation on agricultural land: a case study of the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris breeding at Koobabbie in the northern wheatbelt of Western Australia Denis A. Saunders1, Rick Dawson2, Alison Doley3, John Lauri4, Anna Le Souëf5, Peter R. Mawson6, Kristin Warren5, Nicole White7 1 CSIRO Land and Water, GPO Box 1700, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 2 Department of Parks and Wildlife, Locked Bag 104, Bentley DC, WA 6983, Australia 3 Koobabbie, Coorow, WA 6515 4 BirdLife Australia, 48 Bournemouth Parade, Trigg WA 6029 5 College of Veterinary Medicine, Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, WA 6150 6 Perth Zoo, 20 Labouchere Road, South Perth, WA 6151, Australia 7 Trace and Environmental DNA laboratory, Curtin University, Kent Street, Bentley, WA 6102 Corresponding author: Denis A. Saunders ([email protected]) Academic editor: Klaus Henle | Received 5 August 2014 | Accepted 21 October 2014 | Published 8 December 2014 http://zoobank.org/660B3593-F8D6-4965-B518-63B2071B1111 Citation: Saunders DA, Dawson R, Doley A, Lauri J, Le Souëf A, Mawson PR, Warren K, White N (2014) Nature conservation on agricultural land: a case study of the endangered Carnaby’s Cockatoo Calyptorhynchus latirostris breeding at Koobabbie in the northern wheatbelt of Western Australia. Nature Conservation 9: 19–43. doi: 10.3897/ natureconservation.9.8385 This paper is dedicated to the late John Doley (1937–2007), whose wise counsel and hard work contributed greatly to the Carnaby’s Cockatoo conservation program on Koobabbie. -

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Anatomy of the Dog the Present Volume of Anatomy of the Dog Is Based on the 8Th Edition of the Highly Successful German Text-Atlas of Canine Anatomy

Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. Anatomy of the Dog – Fully illustrated with color line diagrams, including unique three-dimensional cross-sectional anatomy, together with radiographs and ultrasound scans – Includes topographic and surface anatomy – Tabular appendices of relational and functional anatomy “A region with which I was very familiar from a surgical standpoint thus became more comprehensible. […] Showing the clinical rele- vance of anatomy in such a way is a powerful tool for stimulating students’ interest. […] In addition to putting anatomical structures into clinical perspective, the text provides a brief but effective guide to dissection.” vet vet The Veterinary Record “The present book-atlas offers the students clear illustrative mate- rial and at the same time an abbreviated textbook for anatomical study and for clinical coordinated study of applied anatomy. Therefore, it provides students with an excellent working know- ledge and understanding of the anatomy of the dog. Beyond this the illustrated text will help in reviewing and in the preparation for examinations. For the practising veterinarians, the book-atlas remains a current quick source of reference for anatomical infor- mation on the dog at the preclinical, diagnostic, clinical and surgical levels.” Acta Veterinaria Hungarica with Aaron Horowitz and Rolf Berg Budras (ed.) Budras ISBN 978-3-89993-018-4 9 783899 9301 84 Fifth, revised edition Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. -

Hearing in the Starling (Sturn Us Vulgaris): Absolute Thresholds and Critical Ratios

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1986, 24 (6), 462-464 Hearing in the starling (Sturn us vulgaris): Absolute thresholds and critical ratios ROBERT J. DOOLING, KAZUO OKANOYA, and JANE DOWNING University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland and STEWART HULSE Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland Operant conditioning and a psychophysical tracking procedure were used to measure auditory thresholds for pure tones in quiet and in noise for a European starling. The audibility curve for the starling is similar to the auditory sensitivity reported earlier for this species using a heart rate conditioning procedure. Masked auditory thresholds for the starling were measured at a number of test frequencies throughout the bird's hearing range. Critical ratios (signal-to-noise ratio at masked threshold) were calculated from these pure tone thresholds. Critical ratios in crease throughout the starling's hearing range at a rate of about 3 dB per octave. This pattern is similar to that observed for most other vertebrates. These results suggest that the starling shares a common mechanism of spectral analysis with many other vertebrates, including the human. Bird vocalizations are some of the most complex acous METHOD tic signals known to man. Partly for this reason, the Eu ropean starling is becoming a favorite subject for both SUbject The bird used in this experiment was a male starling obtained from behavioral and physiological investigations of the audi the laboratory of Stewart Hulse of 10hns Hopkins University. This bird tory processing of complex sounds (Hulse & Cynx, 1984a, had been used in previous experiments on complex sound perception 1984b; Leppelsack, 1978). -

Mammals of the Nebraska Shortgrass Prairie

Shortgrass Prairie Region Mammal Viewing Tips Mammals can be difficult to see due to their secretive nature. 1. Stay quiet and calm. 2. Be discreet — wear muted clothing and limit fragrances. 3. Look for signs — tracks and scat can tell you if a mammal is in the area, even when you don’t see them. 4. Use binoculars to get a closer look. The shortgrass prairie region includes Always keep a respectful distance Mammals the southwestern corner and Panhandle of from wildlife. Nebraska. This area is made up of short- to 5. Be patient. 6. Go to where the habitat is — visit state mixedgrass prairie and the Pine Ridge. The parks and other public lands. of the shortgrass prairie is the driest and warm- 7. Do your homework — learn what est of the Great Plains grasslands. species of mammals live in the area. This region receives an average of 12 - Nebraska 17 inches of rainfall annually and consists Tracks of buffalo grass and blue grama. The Pine American Badger Ridge is found in northwestern Nebraska Length: 2.5 - 3 in. Shortgrass Width: 2.3 - 2.8 in. and is dominated by ponderosa pine. More Stride: 6 - 12 in. than 300 species of migratory and resident Coyote Prairie birds can be found in the shortgrass prairie Length: 2 - 3.2 in. region, as well as a variety of mammals, Width: 1.4 - 2.4 in. Stride: 8 - 16 in. (walking) plants and other species. Mountain Lion Length: 3 - 4.25 in. Width: 3 - 5 in. Identification Stride: 25 - 45 in. Guide Bobcat Length: 1.8 - 2.5 in. -

Guidelines for Reducing Cockatoo Damage(PDF, 973.6

Guidelines for Reducing Cockatoo Damage Wildlife Management Methods Photo and Figure credits Cover photograph: Sulphur Crested Cockatoo – Nick Talbot Figure 1: Long-billed Corella – Drawing courtesy of Jess Davies Sulphur-crested Cockatoo and Galah – Drawings courtesy of Nic Day Figure 2: Kite to simulate bird of prey – Zoe Elliott Figure 3: Galah – Nick Talbot Figure 4: Long-billed Corella – Ian Temby Figure 5: Cockatoo damage to timber frames – Jim O’Brien Figure 6: Cockatoo damage to outdoor furniture – Ian Temby Figure 7: Cockatoo damage to sporting ground – Mark Breguet Figure 8: Corellas feeding on grain – Mark Breguet Figure 9: Cockatoo damage to crops – Ian Temby © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-1-76047-876-6 pdf/online Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event.