Download the Avian Reproductive Behavior PDF Handout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Parrots in the Wild

Magazine of the World Parrot Trust May 2002 No.51 PsittaScene PsittaSceneParrots in the Wild Kakapo chicks in the nest (Strigops habroptilus) Photo by DON MERTON The most productive season since Kakapo have been intensively managed, 26 chicks had hatched by April. The female called Flossie Members’had two. Seen here are twoExpedition! young she hatched in February 1998. Our report on page 16 describes how she feeds her chicks 900 rimu fruits at each feed - at least four times every night! Supporting parrot conservation in the wild and promoting parrot welfare in captivity. Printed by Brewers of Helston Ltd. Tel: 01326 558000. ‘psittacine’ (pronounced ‘sit a sin’) meaning ‘belonging or allied to the parrots’ or ‘parrot-like’ 0 PsittaPsitta African Grey Parrot SceneScene Trade in Cameroon Lobeke National Park Editor By ANASTASIA NGENYI, Volunteer Biologist, Rosemary Low, WWF Jengi SE Forest Project, BP 6776, Yaounde, Cameroon Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, The forest region of Lobeke in the Southeast corner of Cameroon has TR27 4HB, UK been the focus of attention over the past decade at national and international level, owing to its rich natural resource. Its outstanding conservation importance is due to its abundance of Anastasia Ngenyi. fauna and the rich variety of commercial tree species. Natural CONTENTS resources in the area face numerous threats due to the increased demand in resource exploitation by African Grey Parrot Trade ..................2-3 the local communities and commercial pressure owing to logging and poaching for the bush meat trade. Palm Sunday Success ............................4 The area harbours an unusually high density of could generate enormous revenue that most likely Conservation Beyond the Cage ..............5 forest mammals' particularly so-called "charismatic would surpass present income from illegal trade in Palm Cockatoo Conservation ..............6-7 megafauna" such as elephants, gorillas and parrots. -

Hearing in the Starling (Sturn Us Vulgaris): Absolute Thresholds and Critical Ratios

Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 1986, 24 (6), 462-464 Hearing in the starling (Sturn us vulgaris): Absolute thresholds and critical ratios ROBERT J. DOOLING, KAZUO OKANOYA, and JANE DOWNING University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland and STEWART HULSE Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland Operant conditioning and a psychophysical tracking procedure were used to measure auditory thresholds for pure tones in quiet and in noise for a European starling. The audibility curve for the starling is similar to the auditory sensitivity reported earlier for this species using a heart rate conditioning procedure. Masked auditory thresholds for the starling were measured at a number of test frequencies throughout the bird's hearing range. Critical ratios (signal-to-noise ratio at masked threshold) were calculated from these pure tone thresholds. Critical ratios in crease throughout the starling's hearing range at a rate of about 3 dB per octave. This pattern is similar to that observed for most other vertebrates. These results suggest that the starling shares a common mechanism of spectral analysis with many other vertebrates, including the human. Bird vocalizations are some of the most complex acous METHOD tic signals known to man. Partly for this reason, the Eu ropean starling is becoming a favorite subject for both SUbject The bird used in this experiment was a male starling obtained from behavioral and physiological investigations of the audi the laboratory of Stewart Hulse of 10hns Hopkins University. This bird tory processing of complex sounds (Hulse & Cynx, 1984a, had been used in previous experiments on complex sound perception 1984b; Leppelsack, 1978). -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event. -

AMADOR BIRD TRACKS Monthly Newsletter of the Amador Bird Club June 2014 the Amador Bird Club Is a Group of People Who Share an Interest in Birds and Is Open to All

AMADOR BIRD TRACKS Monthly Newsletter of the Amador Bird Club June 2014 The Amador Bird Club is a group of people who share an interest in birds and is open to all. Happy Father’s Day! Pictured left is "Pale Male" with offspring, in residence at his 927 Fifth Avenue NYC apartment building nest, overlooking Central Park. Perhaps the most famous of all avian fathers, Pale Male’s story 3 (continued below) ... “home of the rare Amadorian Combo Parrot” Dates of bird club President’s Message The Amador Bird Club meeting will meetings this year: be held on: • June 13* Hi Everyone, hope you are enjoying the Friday, June 13, 2014 at 7:30 PM • July 11 warmer weather as I know that some of the • August 8 birds are "getting into the swing of things" and Place : Administration Building, • Sept. 12** producing for all of you breeders. This month Amador County Fairgrounds, • October 10 we will be having a very interesting and Plymouth informative presentation on breeding and • November 14 showing English budgies by Mary Ann Silva. I • December 12 Activity : Breeding and Showing am hoping that you all can attend as it will be English Budgies by Mary Ann (Xmas Party) your loss if you miss this night. Silva *Friday-the-13 th : drive carefully! We will be signing up for the Fair booth Refreshments: Persons with ** Semi-Annual attendance and manning so PLEASE mark it last names beginning with S-Z. Raffle on your calendar. The more volunteers the easier it is for EVERYONE. Set-up is always the Wed. -

Parakeet (Budgerigar)

PARAKEET (BUDGERIGAR) The budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) also known as common pet parakeet or shell parakeet and informally nicknamed the budgie, is a small, long-tailed, seed-eating parrot. Budgerigars are the only species in the Australian genus Melopsittacus, and are found wild throughout the drier parts of Australia where the species has survived harsh inland conditions for the last five million years. Budgerigars are naturally green and yellow with black, scalloped markings on the nape, back, and wings, but have been bred in captivity with colouring in blues, whites, yellows, greys, and even with small crests. Budgerigars are popular pets around the world due to their small size, low cost, and ability to mimic human speech. The species was first recorded in 1805, and today is the third most popular pet in the world, after the domesticated dog and cat. They are very active, playful birds, and they are incredibly intelligent. Some (but not all) budgies learn to talk, there are even budgies have a 100+ word vocabulary! Budgies can easily become finger tame while they are young with some diligent training, even if they were not hand fed as babies. Many owners of fully tamed budgies will swear that their budgie thinks it's a human! Even if a budgie is not tamed, they still make enjoyable pets. Their antics and singing will brighten up any room in your home. And budgies who are not finger tame still can become friendly towards you, and even still learn to talk. Name Many people know them as "parakeets," but their real name is "budgerigar". -

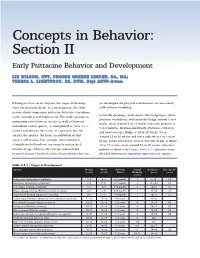

Concepts in Behavior: Section II Early Psittacine Behavior and Development

Concepts in Behavior: Section II Early Psittacine Behavior and Development LIZ WILSON, CVT, PHOEBE GREENE LINDEN, BA, MA; TERESA L. LIGHTFOOT, BS, DVM, D ipl ABVP-A vian Ethologists have yet to map out the stages of develop- yet developed the physical coordination to consistently ment for psittacine birds. As a consequence, the infor- walk without stumbling. mation about companion psittacine behavior is predomi- Generally speaking, small species like budgerigars (Melo- nantly anecdotal and experiential. The wide variation in psittacus undulatus) and cockatiels fledge around 3 to 4 maturation rates between species as well as between weeks, wean around 6 to 11 weeks and enter puberty at individuals within species, as exemplified in Table 3.2.1, 4 to 6 months. Medium-sized birds (Psittacus erithacus further complicates this issue. As a general rule, the and Amazona sp.) fledge at 10 to 12 weeks, wean smaller the species, the faster an individual of that around 12 to 16 weeks and enter puberty at 3 to 4 years species will mature. For example, most cockatiels of age. Larger psittacines such as Ara spp. fledge at about (Nymphicus hollandicus) are sexually mature by 6 12 to 15 weeks, wean around 16 to 20 weeks and enter months of age, whereas the average 6-month-old puberty at about 4 to 5 years. Table 3.2.1 presents more hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) has not detailed information regarding representative species. Table 3.2.1 | Stages of Development Species Fledge Wean Puberty Sexual Geriatric** Life Span47 (weeks) (weeks) Onset -

Problem Sexual Behaviors of Companion Parrots

21 Problem Sexual Behaviors of Companion Parrots Fern Van Sant INTRODUCTION Reproductive behaviors observed in the wild, Psittacine species have become popular as com- such as pair bonding, courtship regurgitation, panion animals because they demonstrate many cavity seeking, nest building, territorial aggres- kinds of social behavior that humans find famil- sion, and copulation, are often displayed in a iar and enjoyable. Such endearing traits as beauty, home setting, though with human “flocks.” Fe- intelligence, and mimicry have led humans to males of some species lay large numbers of eggs adopt them as members of their family. over extended periods of time to a point of com- Recognizing that some of these traits are innate plete physical collapse and failure. The reproduc- and genetically determined will allow for a new tive drive can also lead to behaviors that render and better understanding of companion psittacine the bird difficult or impossible to live with. These behavior and enable us to better predict responses behaviors often include incessant screaming, sud- of different species to the conditions of pet bird den aggression toward favored (or not favored) care. Developing an appreciation for how and humans, and destructive attempts to excavate why innate behaviors can be triggered by specific nests in closets, couches, and drawers. As many actions or conditions will hopefully lead to better species are represented in the pet trade, there ex- and healthier lives for captive psittacine birds. ists extreme variability as to when behaviors will Understanding innate behaviors of companion start, which will be displayed, and how long they psittacines requires an appreciation for the intri- may continue.[7] cate physiologic and hormonal events that adapt a In the wild, the expression of these largely re- species to an environmental niche. -

Three Rare Parrots Added to Appendix I of CITES !

PsittaScene In this Issue: Three Rare Parrots Added To Appendix I of CITES ! Truly stunning displays PPsittasitta By JAMIE GILARDI In mid-October I had the pleasure of visiting Bolivia with a group of avid parrot enthusiasts. My goal was to get some first-hand impressions of two very threatened parrots: the Red-fronted Macaw (Ara rubrogenys) and the Blue-throated Macaw (Ara SceneScene glaucogularis). We have published very little about the Red-fronted Macaw in PsittaScene,a species that is globally Endangered, and lives in the foothills of the Andes in central Bolivia. I had been told that these birds were beautiful in flight, but that Editor didn't prepare me for the truly stunning displays of colour we encountered nearly every time we saw these birds. We spent three days in their mountain home, watching them Rosemary Low, fly through the valleys, drink from the river, and eat from the trees and cornfields. Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, Since we had several very gifted photographers on the trip, I thought it might make a TR27 4HB, UK stronger impression on our readers to present the trip in a collection of photos. CONTENTS Truly stunning displays................................2-3 Gold-capped Conure ....................................4-5 Great Green Macaw ....................................6-7 To fly or not to fly?......................................8-9 One man’s vision of the Trust..................10-11 Wild parrot trade: stop it! ........................12-15 Review - Australian Parrots ..........................15 PsittaNews ....................................................16 Review - Spix’s Macaw ................................17 Trade Ban Petition Latest..............................18 WPT aims and contacts ................................19 Parrots in the Wild ........................................20 Mark Stafford Below: A flock of sheep being driven Above: After tracking the Red-fronts through two afternoons, we across the Mizque River itself by a found that they were partial to one tree near a cornfield - it had sprightly gentleman. -

The English Budgerigarvs

The English All Natural Supplement for Exotic Birds .n. BEAUlY FERTILIlY\ Budgerigar betaearotene vitamins calcium minerals mucoproteins Algae-Feast Spirulina is used by avian experts at by Buddy Walker zoo's and exotic bird breeding centers worldwide. Im Phoenix, Arizona proves fertility in scientific tests. Low in sodium, rich in amino acids. Very concentrated, at tittle goes a long way. A BitofHistory For Cockatiels, Parrots, Softbills, Canaries and Finches. The Budgerigar was unknown •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• outside its native land until Captain Yes, Send me Algae-Feast Spirulina powder now! James Cook discovered Australia D during 1770. It was not until 1794, FREE UPS delivery in Continental USA however, that European naturalist $36.00 -- One Pound Jar IAsk about Wholesale and Bulk I John Gould first reported seeing $83.00 __ Four Pound Jar large flocks of small green parrots Payment amountS:.....- by: 0 check 0 MC 0 Visa dUring his venture to Austrailia. The grass parakeet was a favorite credit card # expo date, _ food of the Aborigines. In fact, the Name on card Phone _ Aborigines call this bird" Betcherry Delivery address, _ gah" (good food), hence the name City, State, Zip _ "Budgerigar:' The Budgerigar has Mail to: Algae-Feast, P.O. Box 719-A, Calipatria, CA 92233 also been termed with several other FAX 619 348-2895 TEL 619 348-2685 names such as shell parrot, grass parakeet and parakeet. Budgerigars were first imported to England during 1840 and soon after wards were imported to the United States. Import dealers imported sev eral hundred thousands of Budgeri gars until 1894 when the Australian government placed a ban on the exportation ofthese birds. -

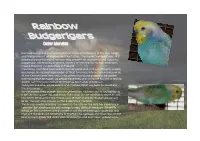

Rainbow Budgies Are a Combination of Several Mutations in the Blue Range and Therefore Not an Independent Mutation

Rainbow budgies are a combination of several mutations in the blue range and therefore not an independent mutation. The name “rainbow” was first used by Keston Foreign Bird Farm who create this wonderful and colourful budgerigar. The Boosey brothers owners of the Keston Foreign Bird Farm create this bird for petshops in England. Previously such bird have been bred in England and on the Continent, usually by change. No respected breeder at that time was interested in these birds. At the Keston farm they only used yellow-faced and goldenfaced opaline whitewing blue an cobalt. As yellow-face they practiced the Mutant 2 and as golden face they used what we know as Australian yellowface. Today we see also visual violets and mauves. What we have to avoid are the grey birds. On the shows they accept also the yellowface Mutant 1 but in my opinion is it better not to use this mutation. The colour of the rainbow is more attrac- tive when we practice the Yellow face Mutant 2 and Australian yellowface birds. The last ones known as the Goldenface rainbow. The problem with breeding rainbow’s is the size of the bird. My experience tells me that finding good whitewings is very difficult because the white- wings on the continent are different from the whitewings in Australia and that are the birds we needed to breed the real rainbow. For that reason the Keston Farm imported Australian whitewings and Australian yellowfaces. YELLOWFACE GROUP YELLOWFACE (MUTANT 1) All varieties in the blue series The standard will be as for all the different varieties in the blue series including grey and should conform in every respect except in the follo- wing details: General body co- as the corresponding white face variety. -

Calcium Metabolism in Grey Parrots: the Effects of Husbandry

This watermark does not appear in the registered version - http://www.clicktoconvert.com Calcium metabolism in grey parrots: the effects of husbandry. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons for the Diploma of Fellowship by Michael David Stanford. August 2005 1 This watermark does not appear in the registered version - http://www.clicktoconvert.com Abstract Hypocalcaemia is a commonly presented pathological condition in the grey parrot (Psittacus e. erithacus) although rarely reported in other psittacine birds. Signs in the adult birds are neurological ranging from mild ataxia to seizures responding rapidly to treatment with calcium or vitamin D3. Captive bred grey parrot chicks suffering from calcium metabolism disorders present as juvenile osteodystrophy with characteristic bowing of the long bones and pathological fractures in severe cases. The condition is comparable to rickets in poultry. This 3 year longitudinal study reports the effects of husbandry changes on the plasma ionised calcium, 25 hydroxycholecalciferol and parathyroid hormone concentrations in two groups of 20 sexually mature healthy grey parrots. The provision of a pellet diet with an increased vitamin D3 and calcium content significantly increased the plasma concentration of ionised calcium and 25 hydroxycholecalciferol over a seed fed control group. The provision of 12 hours daily artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVB 315-285nm spectrum) significantly increased the plasma ionised calcium concentration independent of the diet fed. In the seed group plasma 25 hydroxycholecalciferol concentrations significantly increased after the provision of UVB radiation but not in the pellet group. In a separate study with South American parrots (Pionus spp.) UVB radiation did not have a significant effect on vitamin D3 metabolism.