Problem Sexual Behaviors of Companion Parrots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Cockatiels Free

FREE COCKATIELS PDF Thomas Haupt,Julie Rach Mancini | 96 pages | 05 Aug 2008 | Barron's Educational Series Inc.,U.S. | 9780764138966 | English | Hauppauge, United States How to Take Care of a Cockatiel (with Pictures) - wikiHow A cockatiel is a popular choice for a pet bird. It is a small parrot with a variety of color patterns and a head crest. They are attractive as well as friendly. They are capable of mimicking speech, although they can be difficult to understand. These birds are good at whistling and you can teach them to sing along to tunes. Life Expectancy: 15 to 20 years with proper care, and sometimes as Cockatiels as 30 years though this is rare. In their native Australia, cockatiels are Cockatiels quarrions or weiros. They primarily live in the Cockatiels, a region of the northern part of the Cockatiels. Discovered inthey are the smallest members of the cockatoo family. They exhibit many of the Cockatiels features and habits as the larger Cockatiels. In the wild, they live in large flocks. Cockatiels became Cockatiels as pets during the s. They are easy to breed in captivity and their docile, friendly personalities make them a natural fit for Cockatiels life. These birds can Cockatiels longer be trapped and exported from Australia. These little birds are gentle, affectionate, and often like to be petted and held. Cockatiels are not necessarily fond of cuddling. They simply want to be near you and will be very happy to see you. Cockatiels are generally friendly; however, an untamed bird might nip. You can prevent bad Cockatiels at an early age Cockatiels ignoring bad behavior as these birds aim to please. -

Parrots in the Wild

Magazine of the World Parrot Trust May 2002 No.51 PsittaScene PsittaSceneParrots in the Wild Kakapo chicks in the nest (Strigops habroptilus) Photo by DON MERTON The most productive season since Kakapo have been intensively managed, 26 chicks had hatched by April. The female called Flossie Members’had two. Seen here are twoExpedition! young she hatched in February 1998. Our report on page 16 describes how she feeds her chicks 900 rimu fruits at each feed - at least four times every night! Supporting parrot conservation in the wild and promoting parrot welfare in captivity. Printed by Brewers of Helston Ltd. Tel: 01326 558000. ‘psittacine’ (pronounced ‘sit a sin’) meaning ‘belonging or allied to the parrots’ or ‘parrot-like’ 0 PsittaPsitta African Grey Parrot SceneScene Trade in Cameroon Lobeke National Park Editor By ANASTASIA NGENYI, Volunteer Biologist, Rosemary Low, WWF Jengi SE Forest Project, BP 6776, Yaounde, Cameroon Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, The forest region of Lobeke in the Southeast corner of Cameroon has TR27 4HB, UK been the focus of attention over the past decade at national and international level, owing to its rich natural resource. Its outstanding conservation importance is due to its abundance of Anastasia Ngenyi. fauna and the rich variety of commercial tree species. Natural CONTENTS resources in the area face numerous threats due to the increased demand in resource exploitation by African Grey Parrot Trade ..................2-3 the local communities and commercial pressure owing to logging and poaching for the bush meat trade. Palm Sunday Success ............................4 The area harbours an unusually high density of could generate enormous revenue that most likely Conservation Beyond the Cage ..............5 forest mammals' particularly so-called "charismatic would surpass present income from illegal trade in Palm Cockatoo Conservation ..............6-7 megafauna" such as elephants, gorillas and parrots. -

In Budgerigars

帝京科学大学紀要 Vol.12(2016)pp.29-38 Chorus-like synchronized vocalizations(Big Chorus) in budgerigars 1 Hitomi ABE 1 Fujiro SAKURAI 1 Teikyo University of Science, Faculty of Life & Environmental Sciences-Department of Animal Science Abstract A number of recent studies have reported how budgerigars( Melopsittacus undulatus) are capable of mimicking various behaviors, and that individual vocalizations are strongly influenced by those of other conspecific birds in their vicinity. We examined this effect by placing four budgerigars in separate cages adjacent to each other, and then recording and analyzing all of their vocalizations over a two-week period. Time-based comparisons of the amount of time spent performing warble-songs over a 10 min period revealed a strong correlation between the duration of vocalization when all of the animals were males. However, no such correlation was observed when groups consisted of two males and two females. In the male-only group, whenever one male sang, the others would join in and singing would be synchronized. We repeatedly observed synchronized vocalizations where all of the birds sang together in what could be described as a chorus. While we were unable to demonstrate the functional significance of this behavior, since budgerigars are flocking birds, these synchronized vocalizations were not considered to function as territorial calls or for courtship. Keywords:Budgerigars, Vocal, Warble-song, Chorus-like synchronized, Introduction synchronizing their behaviors to rhythmic changes Budgerigars, the smallest parrots in the order in artificial light and auditory stimuli 7).Thus, Psittaciformes, live in large flocks in Australia while these birds can mimic and synchronize and are known to mimic the sound patterns of their behaviors, the manner in which they are conspecific individuals 1, 2).A recent study reported influenced by the vocalizations of their neighbors that when budgerigars were shown a video of has not yet been clarified. -

Concepts in Behavior: Section II Early Psittacine Behavior and Development

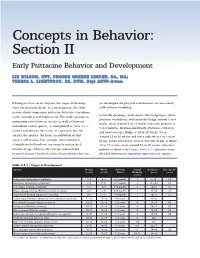

Concepts in Behavior: Section II Early Psittacine Behavior and Development LIZ WILSON, CVT, PHOEBE GREENE LINDEN, BA, MA; TERESA L. LIGHTFOOT, BS, DVM, D ipl ABVP-A vian Ethologists have yet to map out the stages of develop- yet developed the physical coordination to consistently ment for psittacine birds. As a consequence, the infor- walk without stumbling. mation about companion psittacine behavior is predomi- Generally speaking, small species like budgerigars (Melo- nantly anecdotal and experiential. The wide variation in psittacus undulatus) and cockatiels fledge around 3 to 4 maturation rates between species as well as between weeks, wean around 6 to 11 weeks and enter puberty at individuals within species, as exemplified in Table 3.2.1, 4 to 6 months. Medium-sized birds (Psittacus erithacus further complicates this issue. As a general rule, the and Amazona sp.) fledge at 10 to 12 weeks, wean smaller the species, the faster an individual of that around 12 to 16 weeks and enter puberty at 3 to 4 years species will mature. For example, most cockatiels of age. Larger psittacines such as Ara spp. fledge at about (Nymphicus hollandicus) are sexually mature by 6 12 to 15 weeks, wean around 16 to 20 weeks and enter months of age, whereas the average 6-month-old puberty at about 4 to 5 years. Table 3.2.1 presents more hyacinth macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) has not detailed information regarding representative species. Table 3.2.1 | Stages of Development Species Fledge Wean Puberty Sexual Geriatric** Life Span47 (weeks) (weeks) Onset -

Three Rare Parrots Added to Appendix I of CITES !

PsittaScene In this Issue: Three Rare Parrots Added To Appendix I of CITES ! Truly stunning displays PPsittasitta By JAMIE GILARDI In mid-October I had the pleasure of visiting Bolivia with a group of avid parrot enthusiasts. My goal was to get some first-hand impressions of two very threatened parrots: the Red-fronted Macaw (Ara rubrogenys) and the Blue-throated Macaw (Ara SceneScene glaucogularis). We have published very little about the Red-fronted Macaw in PsittaScene,a species that is globally Endangered, and lives in the foothills of the Andes in central Bolivia. I had been told that these birds were beautiful in flight, but that Editor didn't prepare me for the truly stunning displays of colour we encountered nearly every time we saw these birds. We spent three days in their mountain home, watching them Rosemary Low, fly through the valleys, drink from the river, and eat from the trees and cornfields. Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, Since we had several very gifted photographers on the trip, I thought it might make a TR27 4HB, UK stronger impression on our readers to present the trip in a collection of photos. CONTENTS Truly stunning displays................................2-3 Gold-capped Conure ....................................4-5 Great Green Macaw ....................................6-7 To fly or not to fly?......................................8-9 One man’s vision of the Trust..................10-11 Wild parrot trade: stop it! ........................12-15 Review - Australian Parrots ..........................15 PsittaNews ....................................................16 Review - Spix’s Macaw ................................17 Trade Ban Petition Latest..............................18 WPT aims and contacts ................................19 Parrots in the Wild ........................................20 Mark Stafford Below: A flock of sheep being driven Above: After tracking the Red-fronts through two afternoons, we across the Mizque River itself by a found that they were partial to one tree near a cornfield - it had sprightly gentleman. -

Calcium Metabolism in Grey Parrots: the Effects of Husbandry

This watermark does not appear in the registered version - http://www.clicktoconvert.com Calcium metabolism in grey parrots: the effects of husbandry. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons for the Diploma of Fellowship by Michael David Stanford. August 2005 1 This watermark does not appear in the registered version - http://www.clicktoconvert.com Abstract Hypocalcaemia is a commonly presented pathological condition in the grey parrot (Psittacus e. erithacus) although rarely reported in other psittacine birds. Signs in the adult birds are neurological ranging from mild ataxia to seizures responding rapidly to treatment with calcium or vitamin D3. Captive bred grey parrot chicks suffering from calcium metabolism disorders present as juvenile osteodystrophy with characteristic bowing of the long bones and pathological fractures in severe cases. The condition is comparable to rickets in poultry. This 3 year longitudinal study reports the effects of husbandry changes on the plasma ionised calcium, 25 hydroxycholecalciferol and parathyroid hormone concentrations in two groups of 20 sexually mature healthy grey parrots. The provision of a pellet diet with an increased vitamin D3 and calcium content significantly increased the plasma concentration of ionised calcium and 25 hydroxycholecalciferol over a seed fed control group. The provision of 12 hours daily artificial ultraviolet radiation (UVB 315-285nm spectrum) significantly increased the plasma ionised calcium concentration independent of the diet fed. In the seed group plasma 25 hydroxycholecalciferol concentrations significantly increased after the provision of UVB radiation but not in the pellet group. In a separate study with South American parrots (Pionus spp.) UVB radiation did not have a significant effect on vitamin D3 metabolism. -

Strengths and Vulnerabilities of Australian Networks for Conservation of Threatened Birds

Strengths and vulnerabilities of Australian networks for conservation of threatened birds T IM Q. HOLMES,BRIAN W. HEAD,HUGH P. POSSINGHAM and S TEPHEN T. GARNETT Abstract We analysed the supportive social networks asso- making actors within an organizational framework trying ciated with the conservation of six threatened Australian to solve collective problems. The participants in an action bird taxa, in one of the first network analyses of threatened situation (Ostrom, ) for a threatened species may in- species conservation programmes. Each example showed clude those actively involved in the conservation of the contrasting vulnerabilities. The Alligator Rivers yellow bird or those with an interest in, or concern about, the chat Epthianura crocea tunneyi had the smallest social net- bird or a related issue. They may be individuals, or represen- work and no real action was supported. For the Capricorn tatives of NGOs, community groups, land owners, govern- yellow chat Epthianura crocea macgregori the network was ments or corporate actors, interacting for a range of reasons, centred on one knowledgeable and committed actor. The including obtaining or disseminating information, solving orange-bellied parrot Neophema chrysogaster had a strongly problems, negotiating, making decisions, collaborating connected recovery team but gaps in the overall network and seeking physical resources (Ostrom, ; Jepson could limit communication. The recovery teams for the et al., ). The key components of these action situations swift parrot Lathamus discolor and Baudin’s black-cockatoo include key participants, interorganizational collaborations Calyptorhynchus baudinii had strong links among most and social networks. Here, we focus on the social networks stakeholders but had weak ties to the timber industry and of key participants and seek to determine how such net- orchardists, respectively, limiting their capacity to manage works may influence the effective management of biodiver- threatening processes. -

Parrot Life 5

Issue #5 Companionship • Health • Behavior • Aviculture • Conservation Investing in their health. Committed to their future. Green Winged Macaw Ara chloroptera At the forefront of Avian Research. HARI (Hagen Avicultural Research Institute) is a world class Psittacine captive breeding, nutrition and disease research facility. HARI’s continuous progress in animal husbandry have resulted in advancements that enhance the quality of captive breeding and 100% EDIBLE A perfect blend of Fruits, maintenance of companion birds. Consulting Nuts and Legumes with Tropican. with Avian veterinarians, and technicians, HARI works to develop new diets, healthy treats, bird supplements, and is responsible for innovations such as Tropican and Tropimix formulas. These diets combine the highest quality ingredients with strict standards to ensure that your bird receives the highest quality nutrition. www.hagen.com/hari TOTAL NUTRITION Lifetime and High Performance formula for a healthy diet. Understanding the Personality Schema of our PARROT LIFE Birds ContentContent Features By: Sylvie Aubin in this issue page 38 Meet U.S. HARI Parrots Aviculturists Update International By: Melanie Allen Projects By: Mark & Marie Stafford page 5 page 20 page 42 Loving Restraint Where the Wild or Luring techniques for Work is Done large Parrots By: Kevina Williams By: Nathalie Lemieux By: Josee Bermingham page 7 page 34 page 24 Is Your Home Thinking on On the Road to HomeHome Parrot Safe? the Wing Companionship By: Steve Hartman page 8 page 26 page 49 Grooming Observations -

PS 20 4 Nov 08.Qxd

I N THIS I SSUE www.psittascene.org Hope for Thick-billed Parrots Reintroduction of the Kuhl's Lory November 2008 Volume 20 Number 4 PPssiittttaa from the director SWSorld Pccarrot Teerust nnee Glanmor House, Hayle, Cornwall, TR27 4HB, UK. or years we've planned to run a WPT member survey to www.parrots.org learn more about who you are, what you think we're doing Fright, and where you think we could improve our work. We contents deeply appreciate so many of you taking the time to provide us 2 From the Director with such valuable feedback. It has been a pleasure reading over all the responses we received both by mail and online. 4 Rays of Hope Thick-billed Parrot Of course those of us who work for the Trust - either as volunteers 8 An Island Endemic Kuhl’s Lory or staff - are committed to the conservation and welfare of parrots 12 Parrots in Paradise … indeed, just getting the job done is very rewarding in its own Seychelles Black Parrot right. But reviewing the survey results was especially delightful 16 Of Parrots and People because you were so enthusiastic about our work, about PsittaScene , Book Review and the Trust in general. We learned a great deal just as we had 17 Species Profile hoped. We'll take all your comments to heart and incorporate your Lilac-tailed Parrotlet suggestions as we find opportunities. You may see some of your 18 PsittaNews PsittaScene ideas in this issue and others we will work in over time. 19 WPT Contacts Among the outstanding results was your enthusiasm for recommending 20 Parrots in the Wild: Kuhl’s Lory the Trust to others. -

Conservation Implications of Illegal Bird Trade and Disease

CONSERVATION IMPLICATIONS OF ILLEGAL BIRD TRADE AND DISEASE RISK IN PERU A Dissertation by ELIZABETH FRANCES DAUT Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Donald J. Brightsmith Co-Chair of Committee, Markus J. Peterson Committee Members, Renata Ivanek-Miojevic Christian Brannstrom Head of Department, Roger Smith III May 2015 Major Subject: Veterinary Microbiology Copyright 2015 Elizabeth Frances Daut ABSTRACT Trade in wild-caught animals as pets is a global conservation and animal-welfare concern. Illegal and poorly-regulated legal wildlife trade can threaten biodiversity, spread infectious diseases, and result in considerable animal suffering and mortality. I used illegal wildlife trade in Peru, specifically native bird trade, as a case study to explore important aspects and consequences of the trade for domestic markets. With data collected from a five-year market survey and governmental seizure records, I applied a statistical modeling approach to investigate the influence of Peru’s legal export quota system on the country’s illegal domestic bird trade. I used an infectious-disease mathematical modeling approach to analyze how illegal harvest influenced disease dynamics in a wild parrot population. Finally, I used qualitative research methods to investigate the role of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and their members’ philosophical perspectives toward wildlife in combating illegal trade. I found that Peru had a thriving illegal trade in native birds (mostly parrots) for domestic consumers; 150 species were recorded in markets and/or seizures with over 35,250 individuals offered for sale (2007–2011). -

Biodiversity and Human Wellbeing Considerations in Managing the Urban Forest of a Global Biodiversity Hotspot

Biodiversity and human wellbeing considerations in managing the urban forest of a global biodiversity hotspot Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub December 2020 About the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub The Clean Air and Urban Landscapes (CAUL) Hub is funded by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program. The remit of the CAUL Hub is to undertake “Research to support environmental quality in our urban areas”. This includes research on air quality, urban greening, liveability and biodiversity, with a focus on practical implementation of research findings, public engagement and participation by Indigenous Australians. The CAUL Hub is a consortium of four universities: The University of Melbourne, RMIT University, the University of Western Australia and the University of Wollongong. www.nespurban.edu.au Acknowledgements We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands and waters where this research took place, The Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation, and pay our respects to Elders past, present and future. We acknowledge that all cities in Australia were built on Indigenous land, and that this land was never ceded. Please cite this document as Dickinson D. and Ramalho C.E. (2020) Biodiversity and human wellbeing considerations in managing the urban forest of a global biodiversity hotspot. Report prepared by the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub. The Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub and Threatened Species Recovery Hub are funded by the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program Contents Introduction