Guilds in Early Modern Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

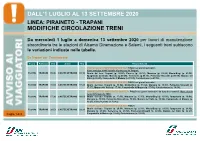

Dall'1 Luglio Al 13 Settembre 2020 Modifiche Circolazione

DALL’1 LUGLIO AL 13 SETTEMBRE 2020 LINEA: PIRAINETO - TRAPANI MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da mercoledì 1 luglio a domenica 13 settembre 2020 per lavori di manutenzione straordinaria tra le stazioni di Alcamo Diramazione e Salemi, i seguenti treni subiscono le variazioni indicate nelle tabelle. Da Trapani per Castelvetrano Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA202 nei giorni lavorativi. Il bus anticipa di 40’ l’orario di partenza da Trapani. R 26622 TRAPANI 05:46 CASTELVETRANO 07:18 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 05:06), Paceco (p. 05.16), Marausa (p. 05:29) Mozia-Birgi (p. 05.36), Spagnuola (p.05:45), Marsala (p.05:59), Terrenove (p.06.11), Petrosino-Strasatti (p.06:19), Mazara del Vallo (p.06:40), Campobello di Mazara (p.07:01), Castelvetrano (a.07:18). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA218 nei giorni lavorativi. R 26640 TRAPANI 16:04 CASTELVETRANO 17:24 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 16:04), Mozia-Birgi (p. 16:34), Marsala (p. 16:57), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 17:17), Mazara del Vallo (p. 17:38), Campobello di Mazara (p. 17:59), Castelvetrano (a. 18:16). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA220 nei giorni lavorativi da lunedì a venerdì. Non circola venerdì 14 agosto 2020. R 26642 TRAPANI 17:30 CASTELVETRANO 18:53 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 17:30), Marausa (p. 17:53), Mozia-Birgi (p. 18:00), Spagnuola (p. 18:09), Marsala (p. 18:23), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 18:43), Mazara del Vallo (p. 19:04), Campobello di Mazara (p. 19:25), Castelvetrano (a. 19:42). -

Curriculum Vitae Scott Kirk, M.A., R.P.A

Curriculum Vitae Scott Kirk, M.A., R.P.A. Doctoral Candidate Telephone: 01-(630)-730-5991 Department of Anthropology Email: [email protected] University of New Mexico RPA ID: 44815837 Updated: 10 November, 2017 Research: My primary research interests focus on defensive strategies, particularly the relationships between fortifications and the landscape, in Medieval and Early Modern European societies. My laboratory experience extends to medieval pottery, American southwest and Mediterranean faunal, and historic artifact analyses as well as the interpretation, analysis and processing of geospatial and satellite data in a wide array of contexts. Additionally, I have experience with survey and excavation in both Sicily and New Mexico. Ongoing Research Projects Social Changes in Fortified Places: Strategy, Defense, and the House of the Military Elite in the Medieval and Early Modern Era. Doctoral Dissertation Research under the supervision of Dr. James L. Boone. 2013-Present The Alcamo Archaeological Project. Currently focused on collecting survey data on the occupation of Monte Bonifato, Western Sicily, from the Late Bronze Age through the Early Modern Period. Project under the direction of Drs. William M. Balco and Michael J. Kolb with myself as the Head of Geospatial Analyses. 2016-Present Education: Graduate Degrees: Ph.D. Anthropology- In Progress Focus on Archaeology University of New Mexico Adviser- Dr. James L. Boone Current GPA: 4.0/4.0 2013-Present M.A. Anthropology Focus on Archaeology Northern Illinois University Adviser- Dr. Michael -

Manifesto Candidati.Cdr

MOD. n.15 CS COMUNE DI PARTANNA ELEZIONE DIRETTA DEL SINDACO E DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE Liste dei candidati per l’elezione diretta alla carica di sindaco e di n° 16 consiglieri comunali che avrà luogo domenica 10 giugno 2018 CANDIDATO CANDIDATO CANDIDATO ALLA CARICA DI ALLA CARICA DI ALLA CARICA DI SINDACO SINDACO SINDACO Anna Maria Nicolò Francesco DE BENEDETTI CATANIA CRINELLI nato a Trapani il 30 Agosto 1966 nato a Partanna il 16 Ottobre 1961 nato a Vimercate (MB) il 14 Maggio 1980 LISTA COLLEGATA LISTA COLLEGATA LISTA COLLEGATA CANGEMI Francesco AMARI Mimma ACCARDO Anna Valeria detta Valeria nato a Partanna 7.08.1959 nata a Castelvetrano il 18.01.1983 nata a Castelvetrano l’ 8.03.1974 CAPPELLO Nicola ATRIA Filippo Massimiliano ACCARDO Nicola nato a Salemi il 3.04.1987 nato a Castelvetrano il 18.08.1971 nato a Palermo il 14.12.1985 CASCIO Filippo BENINATI Raffaele detto Elio AIELLO Giuseppe nato a Partanna il 14.07.1970 nato a Mazara del Vallo il 15.06.1973 nato a Salemi il 26.01.1991 CLEMENZA Leo Massimo CAMPISI Maria Anna BATTAGLIA Valeria nato a Carini il 21.12.1971 nata a Castelvetrano il 15.09.1973 nata a Erice il 22.06.1982 CONTE Vincenza CANGEMI Massimo BIANCO Maria nata a Partanna il 9.12.1968 nato a Erice il 3.02.1970 nata a Salemi il 22.05.1977 DE BENEDETTI Anna Maria CARACCI Rocco detto Nicola GULLO Michele nata a Trapani il 30.08.1966 nato a Partanna il 14.05.1956 nato a Mazara del Vallo il 15.10.1985 DE BLASI Pietro CATANIA Patrizia LI CAUSI Paolo nato a Castelvetrano il 26.12.1978 nata a Mazara del Vallo il 20.03.1985 nato -

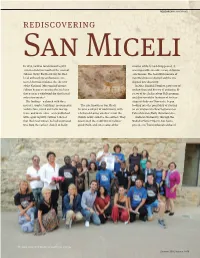

Rediscovering San Miceli

RESEARCH AT ANDREWS rediscovering San Miceli In 1893, Sicilian locals found a gold smaller artifacts had disappeared, it coin in a field just north of the town of was impossible to come to any definitive Salemi, Sicily. Excited about the find, conclusions. The beautiful mosaics of local archaeology enthusiasts con- San Miceli were reburied and the site tacted Antonino Salinas, the director slipped into obscurity. of the National Museum in Palermo. In 2012, Randall Younker, professor of Salinas began excavating the site later archaeology and history of antiquity, di- that year in a whirlwind dig that lasted rector of the Archaeology PhD program only a few weeks.1 and director of the Institute of Archae- His findings—a church with three ology at Andrews University, began mosaics, tombs, buildings, monumental The site, known as San Miceli, looking into the possibility of starting architecture, Greek and Latin inscrip- became a subject of controversy, with an excavation at a New Testament or tions, and more coins—were published scholars debating whether or not the Paleochristian (Early Christian) site. with equal rapidity. Salinas believed church really could be the earliest. They Andrews University, through the that the lower mosaic he had uncovered questioned the credibility of Salinas’ Madaba Plains Project2, has had a was from the earliest church in Sicily. quick work, and since some of the presence in Transjordanian archaeol- The team at the 2015 San Miceli Conference in Sicily. Summer 2016, Volume 7—5 RESEARCH AT ANDREWS ogy for almost 50 years with digs at both Tall Hisban and Tall Jalul in Jordan. -

Architetto Vito Scalisi

Via G. Garibaldi, 9/11 Telefono +39 924 983419 91018 Salemi TP Cell. +39 333 6611311 Posta elettronica [email protected] Architetto Vito Scalisi Dati personali Vito Scalisi Nato a Trapani il 11Gennaio 1967 Codice Fiscale: SCL VTI 67A11 L331C Sposato il 11/07/1996 con Scalisi Marcella, professoressa. Figli: Domenico (1998), Luca Marco e Giulia (2003) Istruzione 1985 - 1986 Liceo Classico Statale "F. D'Aguirre" Salemi, (TP) Diploma di Maturità Classica Conseguito con la votazione di 54/60. 1993 Università degli Studi di Palermo Palermo, (PA) Laurea in Architettura Conseguita il 12 Luglio con la votazione finale di 110/110. Titolo della Tesi: "Piano di recupero del Quartiere Rabato di Salemi (Trapani)". 1993 Università degli Studi di Palermo Palermo, (PA) Abilitazione all'esercizio della professione di Architetto Conseguita nella II° Sessione del 1993. 1994 Ordine Provinciale degli Architetti Trapani, (TP) Iscrizione all'Albo degli Architetti Iscrizione del 14/04/94 al n°666 1995 Università degli Studi di Palermo Palermo, (PA) Collaborazione in attività di ricerca e didattica Tenutasi presso il Dipartimento Città e territorio dell'Università degli Studi di Palermo, nell' ambito del corso di Progettazione Urbanistica. 1997 Ordine degli architetti della Provincia Trapani Corso di Formazione di 120 ore D. Lgs. 494/96 Attestato rilasciato il 24 Settembre 1997. 2001 Ordine degli architetti della Provincia Trapani Master di specializzazione in Restauro dei Monumenti ed Urbano Attestato rilasciato il 08 Aprile 2001. 2009 C.A.D.A. snc Menfi (AG) Seminario di Aggiornamento “Gestione delle terre e rocce da scavo Attestato rilasciato il 16 Ottobre 2009. 2010 Ordine degli architetti della Provincia Trapani Corso di Aggiornamento di 40 ore D. -

Un'esperienza Siciliana

Un’esperienza siciliana COSA È L’A.T.O. TP2 L’ Ambito Territoriale Ottimale Trapani 2 è l’aggregazione di 11 comuni dei 24 della provincia di Trapani per la gestione dei rifiuti urbani. QUALI COMUNI Petrosino, Mazara del Vallo, Castelvetrano, Campobello di Mazara, Gibellina , Salaparuta , Vita Santa Ninfa, Partanna, Salemi e Poggioreale. UTENTI Gli utenti dell’Ambito sono 138.201. ESTENSIONE Kmq L’Ambito si estende su una superficie di kmq 1.054,99. LA SOCIETÀ PRIMA DEL 2007* MEZZI FORZA LAVORO IL SERVIZIO DI RACCOLTA 87% 49 181 in appalto di proprietà uomini (nolo a caldo) 13% 48 Costo annuo 3 milioni di euro in house nolo a caldo circa 0 Centri di raccolta 8,55% RD 0 Comuni serviti da RD “porta porta” CdA Assemblea dei Collegio Revisore dei Amministratore Soci sindacale conti Delegato * dati aggiornati al 31 dicembre 2006 LA NUOVA STRUTTURA SOCIETARIA DAL 2007 CdA e AD Direttore Generale Amministratore dall’ottobre 2009 Unico dal novembre 2007 Assemblea dei soci Assemblea di coordinamento Responsabile dei servizi Intercomunal e - Finanziario - Impianti - Gestione Integrata Rifiuti DENTRO LA STRUTTURA /1 Amministratore Unico Ufficio di Ufficio Stampa e Gabinetto Comunicazione Direttore Generale Servizio Servizio Gestione Finanziario Integrata Rifiuti Servizio Impianti DENTRO LA STRUTTURA/2 SERVIZIO FINANZIARIO SERVIZIO IMPIANTI SERVIZIO • Ufficio • Ufficio discarica e GESTIONE INTEGRATA RIFIUTI Provveditorato e polo tecnologico • Ufficio pianificazione e Tesoreria gestione sistema di raccolta e • Ufficio formulari carta dei servizi • -

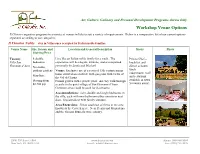

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

DALL’1 LUGLIO AL 13 SETTEMBRE 2020 LINEA: PIRAINETO - TRAPANI MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da mercoledì 1 luglio a domenica 13 settembre 2020 per lavori di manutenzione straordinaria tra le stazioni di Alcamo Diramazione e Salemi, i seguenti treni subiscono le variazioni indicate nelle tabelle. Da Trapani per Castelvetrano Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA202 nei giorni lavorativi. Il bus anticipa di 40’ l’orario di partenza da Trapani. R 26622 TRAPANI 05:46 CASTELVETRANO 07:18 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 05:06), Paceco (p. 05.16), Marausa (p. 05:29) Mozia-Birgi (p. 05.36), Spagnuola (p.05:45), Marsala (p.05:59), Terrenove (p.06.11), Petrosino-Strasatti (p.06:19), Mazara del Vallo (p.06:40), Campobello di Mazara (p.07:01), Castelvetrano (a.07:18). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA218 nei giorni lavorativi. R 26640 TRAPANI 16:04 CASTELVETRANO 17:24 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 16:04), Mozia-Birgi (p. 16:34), Marsala (p. 16:57), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 17:17), Mazara del Vallo (p. 17:38), Campobello di Mazara (p. 17:59), Castelvetrano (a. 18:16). CANCELLATO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS PA220 nei giorni lavorativi da lunedì a venerdì. Non circola venerdì 14 agosto 2020. R 26642 TRAPANI 17:30 CASTELVETRANO 18:53 Orario del bus: Trapani (p. 17:30), Marausa (p. 17:53), Mozia-Birgi (p. 18:00), Spagnuola (p. 18:09), Marsala (p. 18:23), Petrosino-Strasatti (p. 18:43), Mazara del Vallo (p. 19:04), Campobello di Mazara (p. 19:25), Castelvetrano (a. 19:42). -

Campionato Provinciale Giovanissimi Girone “A” Calendario

CAMPIONATO PROVINCIALE GIOVANISSIMI GIRONE “A” CALENDARIO GIRONE DI ANDATA 1^ GIORNATA JUVENILIA ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI 24/11/14 15:15 NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO CUSTONACI 29/11/14 15:00 PACECO 1976 ADELKAM 24/11/14 18:00 TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB OLIMPIA SALEMI 24/11/14 15:15 Riposa.............. MAZARA CALCIO 2^ GIORNATA ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO 03/12/14 15:15 ADELKAM TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB 02/12/14 15:30 CUSTONACI PACECO 1976 01/12/14 15:30 OLIMPIA SALEMI MAZARA CALCIO 06/12/14 15:30 Riposa.............. JUVENILIA 3^ GIORNATA MAZARA CALCIO ADELKAM 14/12/14 11:00 NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO JUVENILIA 13/12/14 15:00 PACECO 1976 ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI 08/12/14 18:00 TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB CUSTONACI 08/12/14 15:15 Riposa.............. OLIMPIA SALEMI 4^ GIORNATA ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB 17/12/14 15:15 ADELKAM OLIMPIA SALEMI 16/12/14 15:30 CUSTONACI MAZARA CALCIO 15/12/14 15:30 JUVENILIA PACECO 1976 15/12/14 15:15 Riposa............. NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO 5^ GIORNATA MAZARA CALCIO ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI 11/01/15 11:00 OLIMPIA SALEMI CUSTONACI 10/01/15 15:30 PACECO 1976 NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO 5/01/15 18:00 TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB JUVENILIA 5/01/15 15:15 Riposa.............. ADELKAM 6^ GIORNATA ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI OLIMPIA SALEMI 14/01/15 15:15 CUSTONACI ADELKAM 12/01/15 15:30 JUVENILIA MAZARA CALCIO 12/01/15 15:15 NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB 17/01/15 15:00 Riposa.............. PACECO 1976 2 7^ GIORNATA ADELKAM ACCADEMIA SPORT TRAPANI 20/01/15 15:30 MAZARA CALCIO NUOVA SPORTIVA DEL GOLFO 25/01/15 11:00 OLIMPIA SALEMI JUVENILIA 24/01/15 15:30 TRAPANI JUNIOR CLUB PACECO 1976 19/01/15 15:15 Riposa............. -

Comune Di Buseto Palizzolo Provincia Di Trapani

COMUNE DI BUSETO PALIZZOLO PROVINCIA DI TRAPANI *********** Copia di Deliberazione del Consiglio Comunale N. 13 Rep. Data 19.03.2015 OGGETTO: Adesione del Comune di Erice all'Unione dei Comuni Elimo Ericini.- L'anno Duemilaquindici, il giorno Diciannove del mese di Marzo su invito del Presidente del Consiglio, in seguito ad appositi inviti, distribuiti a domicilio di ciascuno nei modi e nei termini di legge, si è adunato il Consiglio Comunale in sessione ordinaria di prima convocazione. Presiede l'adunanza il Consigliere Sig.ra Angela Mustazza Risultano presenti i seguenti Consiglieri: CONSIGLIERI Pres. Ass. CONSIGLIERI Pres. Ass. 1 MUSTAZZA Angela si 9 SIMONTE Pietro si 2 VULTAGGIO Veronica si 10 SIMONTE Maria si 3 ADRAGNA Antonella si 11 FERLITO Alessandro si 4 BARONE Giuseppe si 12 LOMBARDO Francesco si 5 GRAMMATICO Vincenza si 13 DE FILIPPI Giuseppina si 6 FILEGGIA Angelo si 14 COSTA Filippo SI 7 COLOMBA Giuseppa si 15 MAIORANA Roberto si 8 TANTARO Giovanni si PRESENTI N. 12 ASSENTI N. 3 Scrutatori i Sigg.: Adragna Antonella, Vultaggio Veronica e De Filippi Giuseppina. Partecipa all'adunanza il Segretario Generale Dr. Vincenzo Barone che procede alla verbalizzazione dei provvedimenti. Risultato legale il numero degli intervenuti, il Presidente dichiara aperta la seduta per trattare l'O.d.G. soprasegnato. Per l'Amministrazione sono presenti il Sindaco, Vice Sindaco e l'Assessore Randazzo. Si sottopone ad approvazione la seguente proposta di deliberazione. IL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE Premesso che: - a seguito delle modifiche operate dalla Legge Cost. n.3/2001 all'arti 18 della Costituzione, gli enti locali sono l'espressione della P.A. -

ART HISTORY of VENICE HA-590I (Sec

Gentile Bellini, Procession in Saint Mark’s Square, oil on canvas, 1496. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice ART HISTORY OF VENICE HA-590I (sec. 01– undergraduate; sec. 02– graduate) 3 credits, Summer 2016 Pratt in Venice––Pratt Institute INSTRUCTOR Joseph Kopta, [email protected] (preferred); [email protected] Direct phone in Italy: (+39) 339 16 11 818 Office hours: on-site in Venice immediately before or after class, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION On-site study of mosaics, painting, architecture, and sculpture of Venice is the primary purpose of this course. Classes held on site alternate with lectures and discussions that place material in its art historical context. Students explore Byzantine, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque examples at many locations that show in one place the rich visual materials of all these periods, as well as materials and works acquired through conquest or collection. Students will carry out visually- and historically-based assignments in Venice. Upon return, undergraduates complete a paper based on site study, and graduate students submit a paper researched in Venice. The Marciana and Querini Stampalia libraries are available to all students, and those doing graduate work also have access to the Cini Foundation Library. Class meetings (refer to calendar) include lectures at the Università Internazionale dell’ Arte (UIA) and on-site visits to churches, architectural landmarks, and museums of Venice. TEXTS • Deborah Howard, Architectural History of Venice, reprint (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003). [Recommended for purchase prior to departure as this book is generally unavailable in Venice; several copies are available in the Pratt in Venice Library at UIA] • David Chambers and Brian Pullan, with Jennifer Fletcher, eds., Venice: A Documentary History, 1450– 1630 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001). -

Processo Bagliesi

CORTE DI ASSISE DI APPELLO PALERMO IN NOME DEL POPOLO ITALIANO LA CORTE DI ASSISE DI APPELLO DI PALERMO N° 31/2008 Sent. SEZIONE PRIMA N 19/2008 R.G. L’anno duemilaotto il giorno nove del mese di dicembre composta dai Sigg.ri : Notizie di Reato N° 15489/2005 1 Dott. Innocenzo LA MANTIA Presidente Proc. Rep. PA 2 Dott. Alfredo MONTALTO Consigliere Art.___________ Camp. Penale 3 Sig. Gregoria MAURO Giudice Popol. 4 Sig. Vito PAMPALONE “ “ Art.___________ 5 Sig. Pietra MESSINEO “ “ Campione Civile 6 Sig. Giuseppa RE “ “ Compilata scheda 7 Sig. Simone LI MULI “ “ per il Casellario e 8 Sig. Emanuele FANARA “ “ per l’elettorato Addì___________ Con l’intervento del Sost. Procuratore Generale Dott.ssa DANIELA GIGLIO e con l’assistenza del Cancelliere Antonella FOTI Depositata in ha pronunziato la seguente Cancelleria Addì___________ S E N T E N Z A Irrevocabile il ______________ nei confronti di BAGLIESI Salvatore nato a Partinico (PA) il 06.02.1958 ivi res.te in Via delle Capre n.118 (dom. eletto) Arr. il 04.11.2005 scarc. il 18.12.2007 PRESENTE DIFENSORI: Avv. Mario Maggiolo Foro di Pisa Avv. Lucia Indellicati Foro di Termini Imerese con studio in Palermo Via Terrasanta, 93. PARTE CIVILE: LA CORTE Iolanda, nata a Monreale il 02.01.1970 ivi res.te in Via Verdi n.14, in proprio e n.q. di genitore esercente la potestà sui figli minori: PAGE 1 - ROSSELLO Provvidenza, nata a Palermo il 18.08.1990; - ROSSELLO Francesco, nato a Palermo il 18.02.1995; - ROSSELLO Elena, nata a Palermo il 17.07.1999; Tutti rappresentati e difesi dall’avv.