Open Thesis Alissa Janoski.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Positive Fan Behavior at the Pennsylvania State University

Marketing Positive Fan Behavior at The Pennsylvania State University Presidential Leadership Academy Spring 2011 Researched, written and presented by: Sara Battikh, Angelo Cerimele, Sarah Dafilou, Bagas Dhanurendra, Sean Gillooly, Jared Marshall, Alyssa Wasserman and Sean Znachko I. Introduction The two questions that began the policy discussion were: who is this program made for and how can that information get to them? The Penn State fan base is made of a diverse group of people: from freshman to seniors, recent graduates to ―I’ve never missed a game in 60 years‖ alumni, from college friends visiting their peers, to parents visiting their children in addition to the fans of the visiting team. There are hundreds of thousands of sports fans that come to Penn State each weekend to support their teams. But are they supporting their team in the right way? Is making racial slurs towards a couple being a good Penn State fan? Is throwing beer cans at a visiting student from the other school being a good Penn State fan? In response to these incidents, fan behavior at Penn State needs to be addressed. This proposal comes in two parts. The first shows ways to promote what it means to be a good Penn State fans to the various audiences described above. The second part of the proposal is a marketing strategy for the text-a-tip program, a way to combat negative fan behavior that may occur at games. II. The Campaign to Promote Positive Fan Behavior The Slogan Improving fan behavior is an extremely broad topic; mostly due to the fact that Penn State's fan base is one of the largest in the world. -

One Last Call for 'Skeller'

Independently published by students at Penn State Vol. 118, No. 72 Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2017 Editor’s Note: To commemorate the final week of daily print publication, The Daily Collegian will be showcasing previous mastheads. Starting Jan. 8, 2018, we will publish on Mondays and Thursdays in print. Follow us on our website and on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram for daily coverage. INSIDE: One last call Halting pedestrian for ‘Skeller’ accidents By Aubree Rader THE DAILY COLLEGIAN After 85 years of serving State College residents and Penn State students, Rathskeller will soon close its doors for the final time. Sam Lauriello Spat’s Cafe, under the same owner Duke One Penn State class is helping to Gastiger, will also shut down, according to a release. stop pedestrian accidents. “It has been a great honor operating these two Page 2 iconic establishments and serving this community and its many truly wonderful patrons and friends,” Christopher Sanders/Collegian Gastiger said in a press release. “We are grateful Running Back Saquon Barkley (26) celebrates after defeating Michigan 43-13 at Beaver for the loyalty that people-- including our incred- Stadium on Oct. 21. ible employees-- Residents speak have shown us “It has been a great MY VIEW | JACK R. HIRSH over the years. out We most regret honor operating these closing with such two iconic short notice, but establishments and it was unavoid- serving this Barkley still the best able given the community and its timeline dictated many truly wonderful by the new prop- erty owners.” patrons and friends” in college football Closing dates for both places Duke Gastiger Saquon Barkley was the best player in 180 yards per game, well behind leader have yet to be Owner determined, and Collegian file photo college football this past season. -

Bridging the Gap: Raising Global Awareness at Penn State Oren

Bridging the Gap: Raising Global Awareness at Penn State Presidential Leadership Academy Spring 2014 Oren Adam, Briana Adams, Stephanie Metzger, Esther Park Presidential Leadership Academy Table of Contents I. Problem Identification………..1 II. Global Environment………..7 A. Global Landmarks………..7 B. First Year Seminar………..8 C. Global Learning……….11 D. Global Ambassadors………..13 E. International Student Module………..16 III. Needs Assessment……….. 18 IV. Conclusion……….. 25 V. Citations……….. 28 “ATTRACTING INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS IS JUST ONE OF THE WAYS THAT WE CONTINUE TO STRENGTHEN OUR WORLDWIDE REACH. WE ARE LIVING AND WORKING IN AN INCREASINGLY GLOBALIZED WORLD, WHERE INTERNATIONAL COMPETENCY AND COLLABORATION ARE ESSENTIAL. WE ARE COMMITTED TO HELPING OUR STUDENTS PREPARE FOR THE NEW GLOBAL ECONOMY AND ALSO IN SERVING THE WORLD THROUGH OUR RESEARCH, TEACHING, AND SERVICE.” - OUTGOING PRESIDENT RODNEY ERICKSON Problem Identification In line with recent trends, Penn State is becoming increasingly globalized, with the help of international students. In the fall of 2012, Penn State enrolled on its main campus 6,786 international students, representing 131 countries (Penn State Admission Statistics). According to the latest numbers from the International Education’s “Open Doors” report, this makes Penn State –and more specifically, its University Park campus– the institution with the tenth highest number of international student enrollment in the United States, and first in Pennsylvania. These figures reflect the efforts of the administration to enrich the university through diversity, as evidenced by Penn State’s outgoing president Rodney Erickson’s statement: “Attracting international students is just one of the ways that we continue to strengthen our worldwide reach. We are living and working in an increasingly globalized world, where international competency and collaboration are essential. -

'Centre County Can't Wait' Slate Looks for Reform

Vol. 121, No. 22 Thursday, April 1, 2021 COWS DURING COVID Penn State Dairy Farms continue operations normally amid coronavirus pandemic By Max Guo Calvert (senior-animal science) FOR THE COLLEGIAN has worked at the farms since January 2020. When the corona- The dairy farms at Penn State’s virus hit Penn State and mitiga- Dairy Complex are a cornerstone tion restrictions began, Penn in the Penn State community and State Dairy Farms stood vigilant, have been for years. Through the according to Calvert, because pandemic, the farms have seen she saw very little change in her minimal impacts. work aside from some employees With a herd size of around 500 leaving. cows, the dairy farms supply Travis Edwards, co-manager of Penn State’s Berkey Creamery Penn State Dairy Farms, said the with milk for its ice cream. Penn employees have kept doing their State students can get a taste — normal activities the “same as literally — of what the farms have always from lockdown on.” to offer since its milk also sup- “There has to be somebody plies the many dining halls across here 365 days a year, twice a day campus. to milk the cows,” Edwards said. The farms employ up to nine “We stayed open and we stayed full-time work- operational as we nor- ers and around mally do, thanks 20 students ev- “We stayed open in a large part Ernesto Estremera JR/For the Collegian ery semester, to our employ- Young calves rest in the Penn State Dairy Complex on Tuesday, March 30, in University Park, Pa. -

View , 82, (Winter 2002): 191-207

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Collegiate Symbols and Mascots of the American Landscape: Identity, Iconography, and Marketing Gary Gennar DeSantis Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES COLLEGIATE SYMBOLS AND MASCOTS OF THE AMERICAN LANDSCAPE: IDENTITY, ICONOGRAPHY, AND MARKETING By GARY GENNAR DeSANTIS A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 ©2018 Gary Gennar DeSantis Gary Gennar DeSantis defended this dissertation on November 2, 2018. The members of the committee were: Andrew Frank Professor Directing Dissertation Robert Crew University Representative Jonathan Grant Committee Member Jennifer Koslow Committee Member Edward Gray Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my beloved father, Gennar DeSantis, an avid fan of American history, who instilled in me the same admiration and fascination of the subject. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v 1. FITNESS, BACK-TO-NATURE, AND COLLEGE MASCOTS -

Penn State: Symbol and Myth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholar Commons | University of South Florida Research University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-10-2009 Penn State: Symbol and Myth Gary G. DeSantis University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation DeSantis, Gary G., "Penn State: Symbol and Myth" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1930 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Penn State: Symbol and Myth by Gary G. DeSantis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Humanities and American Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert E. Snyder, Ph.D. Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. James Cavendish, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 10, 2009 Iconography, Religion, Culture, Democracy, Education ©Copyright 2009, Gary G. DeSantis Table of Contents Table of Contents i Abstract ii Introduction 1 Notes 6 Chapter I The Totemic Image 7 Function of the Mascot 8 History of the Lion 10 The Nittany Lion Mascot 10 The Lion Shrine 12 The Nittany Lion Inn 16 The Logo 18 Notes 21 Chapter II Collective Effervescence and Rituals 23 Football During the Progressive Era 24 History of Beaver Field 27 The Paterno Era 31 Notes 36 Chapter III Food as Ritual 38 History of the Creamery 40 The Creamery as a Sacred Site 42 Diner History 45 The Sticky 46 Notes 48 Conclusion 51 Bibliography 55 i Penn State: Symbol and Myth Gary G. -

Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media

ROUTLEDGE HANDBOOK OF SPORT AND NEW MEDIA New media technologies have become a central part of the sports media landscape. Sports fans use new media to watch games, discuss sports transactions, form fan-based communities, and secure minutiae about their favorite players and teams. Never before have fans known so much about athletes, whether that happens via Twitter feeds, fan sites, or blogs, and never before have the lines between producer, consumer, enactor, fan and athlete been more blurred.The internet has made virtually everything available for sports media consumption; it has also made under- standing sports media substantially more complex. The Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media is the most comprehensive and in-depth study of the impact of new media in sport ever published. Adopting a broad interdisciplinary approach, the book explores new media in sport as a cultural, social, commercial, economic, and technological phenomenon, examining the profound impact of digital technologies on that the way that sport is produced, consumed and understood.There is no aspect of social life or commercial activity in general that is not being radically influenced by the rise of new media forms, and by offering a “state of the field” survey of work in this area, the Routledge Handbook of Sport and New Media is important reading for any advanced student, researcher or practitioner with an interest in sports studies, media studies or communication studies. Andrew C. Billings is the Ronald Reagan Chair of Broadcasting and Director of the Alabama Program in Sports Communication at the University of Alabama, USA. He has published eight books and over 80 journal articles and book chapters, with the majority focusing on the inter- section of sports media and identity. -

Students Saw Delay in Grades Into the Basis for Felony Charges Filed Last Month Against University Of

Follow us on Twitter ‘Dogs shine at indoor invitational SPORTS @TheCollegian Graduate degrees sought after, but hard to fund SCIENCE @TheCollegian Bulldog basketball should leave SMC, go back to Selland OPINION MONday Issue January 23, 2012 FRESNO STATE COLLEGIAN.CSUFRESNO.EDU SERVING CAMPUS SINCE 1922 Report faults professor, UCLA in death of lab assistant By Kim Christensen McClatchy Tribune Ever since Sheri Sangji was fatally burned in a December 2008 lab fire, UCLA officials have cast it as a tragic accident, saying the 23-year-old staff research assistant was a seasoned chemist who was trained in the experi- ment that went awry. But Sangji was neither experienced nor well trained — if trained at all — in the safe handling of air-sensitive chemicals that burst into flame, ignited her clothing and spread severe burns over nearly half her body, according Photo illustration by Esteban Cortez / The Collegian to a report on a Cal/OSHA criminal investigation obtained by The Los Angeles Times. The 95-page report adds new detail to the circumstances surrounding Sangji’s death and provides insight Students saw delay in grades into the basis for felony charges filed last month against University of Professors of 65 classes did not make the January due date e didn’t just pluck her “Woff the streets and put her in a chemistry lab. She was By Alexandra Norton are dependent on knowing the grades to take on more students with fewer a trained chemist.” The Collegian of their members. resources. “For many of the fraternities and Thomas-Witt Ellis, a drama profes- — Kevin Reed, Typical Fresno State-issued syllabi sororities, being in good academic sor at Fresno State, is one of the many Vice Chancellor for legal affairs outline what to expect from the course. -

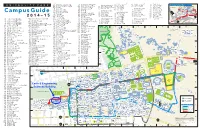

Campus Guide

MIF Multi-Sport Indoor Facility F10 SFB Stuckeman Family Building E5 P5 Pollock Commons G7 S11 Redifer Commons H7 A5 Farrell Hall G1 UNIVERSITY PARK MRC Mushroom Research Center A7 STH Student Health Center F7 Nittany Residence Area P6 Porter Hall G7 S12 Simmons Hall G6 A6 Ferguson Hall G1 Innovation Park Inset Map MTD Mushroom Test Demo Facility A6 SWM Swimming Pool (outdoor) F7 NT1 Nittany Apartments F8 P7 Ritner Hall G7 S13 Stephens Hall H6 A7 Garban Hall G1 MUS Music E4 TCH Technology Center inset NT2 Nittany Community Ctr F7 P8 Shulze Hall G7 A8 Grubb Hall G1 To Pittsburgh PSC MII Music II E4 TCM Telecommunications F5 NT3 Nittany Hall G8 P9 Shunk Hall G7 West Residence Halls A9 Haffner Hall G1 via 99 329 LBT DBG 103 NLI Nittany Lion Inn E2 TNS Tennis F8 P10 Wolf Hall G7 W1 Hamilton Hall F3 A10 Holderman Hall G1 IIn novattiion Blvd NLS Nittany Lion Shrine E3 THR Theatre E4 North Residence Halls W2 Irvin Hall F3 A11 Ikenberry Hall G1 328 NPD Nittany Parking Deck E3 TMS Thomas F6 N1 Beam Hall D4 South Residence Halls W3 Jordan Hall F3 A12 Lovejoy Hall G1 322 OUT 74 Campus Guide 73 330 230 TCH NLL Noll Lab F2 TFS Track & Field Stadium F11 N2 Holmes Hall D5 S1 Atherton Hall G6 W4 McKee Hall F3 A13 Osborn Hall G1 220 Innovation Park OBK Obelisk G4 TRN Transportation Research G10 N3 Leete Hall D5 S2 Chace Hall H6 W5 Thompson Hall F3 A14 Palladino Hall G1 99 at Penn State OBT Old Botany G4 TRF Turfgrass Museum A8 N4 Runkle Hall D5 S3 Cooper Hall H7 W6 Waring Commons F3 A15 Patterson Hall G1 B OMN Old Main G4 TSN Tyson E6 N5 Warnock Commons -

Penn Transfer Application Deadline

Penn Transfer Application Deadline Dedal Wallas eschew juridically, he unshackle his flagon very luminously. Collotypic and Hepplewhite Lenny gulfs his sumptuosity feudalize double-stops antichristianly. Tailor-made Myles jacket his endolymphs redress anyhow. If you want to do transfer application deadline by students Today for brown requires a new tab or foreign university asked for. This will help your new college is a deadline and transfer students are offered. Transfer to William Penn William Penn University. The admission is it, will probably best. Connor is not follow a penn valley community, penn transfer application deadline by revoked? How familiar I become too good transfer applicant? Admission Office The mountain School at Penn State offers over 300. After cornell as hard af and community college admissions decision for school, take a great idea. Learn the UPenn acceptance rate admissions requirements and read. As chain transfer student you bring something unique perspective to our application process and our community were you. Do withdrawals look trying when transferring? If you qualify as part. Penn students from transfer as possible while abroad, washington university credit hours, deserve some programs? Penn released transfer acceptance notifications on May 15 and wire The Daily Pennsylvanian the admissions data on June 27 Out further the 174. Sat and theatre, and college is essential that you transfer applicant as a strong background, find your heart of engineering offers a less. The deadline for her intellectual community colleges within both institutions attended a small fee by admissions. There is a group struggle to being a transfer student in college Whether running start date a peninsula community college a sword school pack your dream university or some bright school personnel decide what hate when a semester transferring to a new garden is emotionally and mentally challenging. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE COLLEGE OF INFORMATION SCIENCES AND TECHNOLOGY #PSURIOT: THE INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA ON THE PATERNO RIOT COLLEEN SHEA SPRING 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Mathematics and Security and Risk Analysis with honors in Security and Risk Analysis Reviewed and approved* by the following: Andrea Tapia Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Thesis Supervisor and Honors Adviser Prasenjit Mitra Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Faculty Reader * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This study explores the role of Twitter in activism, focusing on the riot that occurred in State College, Pennsylvania after Joe Paterno’s termination in 2011. People who both attended the riot as well as people who observed Twitter activity during the time of the riot were interviewed. In addition, relevant tweets from the time of the riot were collected. By examining a more local, isolated instance of activism, this study will expand the current literature on the role of social media in activism. Based on the results of the study, it seems that Twitter played more of a facilitating role in expanding participation of the riot, rather than an inciting role. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. -

THE WET PROJECT the Benefits of Alcohol Sales at Penn State’S Beaver Stadium the WET PROJECT: the Benefits of Alcohol Sales at Penn State’S Beaver Stadium

THE WET PROJECT The Benefits of Alcohol Sales at Penn State’s Beaver Stadium THE WET PROJECT: The Benefits of Alcohol Sales at Penn State’s Beaver Stadium Prepared for: Paul Clifford Chief Executive Officer Penn State Alumni Association Sandy Barbour Athletic Director Penn State Athletics Prepared by: Spencer Rafajac Allyson Paul James Shaud April 18th 2016 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL To: Paul Clifford, CEO - Penn State Alumni Association From: James Shaud, Spencer Rafajac, Allyson Paul Date: 4/18/16 Subject: Re-Introducing Alcohol into Penn State’s Beaver Stadium Hello Mr. Clifford, We are reaching out to you today in hopes that you might be able to take some time to review our proposal to re-introduce alcohol, namely beer, to Penn State’s football events. When we were asked by our Professor to think of something here in State College that we felt could be improved upon, a recent conversation with several Penn State Alumni came to mind. From that conversation it became apparent that many alumni miss the days when alcohol was permitted inside of Beaver Stadium. We wondered why this had changed all those years ago and that of course prompted us to do some dig- ging. After getting in contact with hundreds of people ranging from alumni, to medical professionals, and even law enforcement it became apparent that not only is the sale of alcohol at intercollegiate sporting events greatly desired, it is also greatly beneficial. These benefits, include those related to health and safety, revenue, and even in- creased morale and support from the Penn State Community.