The Pennsylvania State University The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

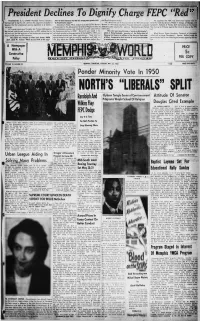

President Declines to Dignify Charge FEPC “Red

■ 1 —ft, President Declines To Dignify Charge FEPC “Red WASHINGTON, D. C.-(NNPA)-President Truman Saturday ment of some Senators that the fair employment practice bill and Engel,s began to write." | The argument that FEPC was Communist Inspired wai ve ) had declined to dignify with comment the argument of Southern is of Communist origin'** Mr. White was one of those present al the While House con hemently made by Senator* Walter F. George, of Georgia, and ference in 194) which resulted in President Roosevelt issuing an I Senator* that fair employment practice legislation is of Commu- According to Walter White, executive secretary of the Nation Spessard I. Holland, of Florida, both Democrats, on the Senate al Association for the Advancement of Colored People the fdea of I ni*t origin. executive aider creating the wartime fair Employment Practice floor during the filibuster ogaintl the motion to take up the FEPC At hi* press conference Thursday, Mr. Truman told reporters fair employment practices was conceived "nineteen years before Committee. ' bill. I that he had mode himself perfectly clear on FEPC, adding that he the Communists did so in 1928." He said it was voiced in the the order was issued to slop a "march on-Woshington", I did not know that the argument of the Southerners concerning the call which resulted in the organization of lhe NAACP in 1909, and which A. Philip Randolph, president of lhe Brotherhood of Whert Senotor Hubert Humphrey, Democrat, of Minnesota I origin of FEPC deserved any comment. that colored churches and other organizations "have cried out Sloeping Car Porters, an affiliate of lhe American Federation called such a charge ’ blasphemy". -

A History of Sport in British Columbia to 1885: Chronicle of Significant Developments and Events

A HISTORY OF SPORT IN BRITISH COLUMBIA TO 1885: CHRONICLE OF SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS AND EVENTS by DEREK ANTHONY SWAIN B.A., University of British Columbia, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES School of Physical Education and Recreation We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1977 (c) Derek Anthony Swain, 1977 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Depa rtment The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ii ABSTRACT This paper traces the development of early sporting activities in the province of British Columbia. Contemporary newspapers were scanned to obtain a chronicle of the signi• ficant sporting developments and events during the period between the first Fraser River gold rush of 18 58 and the completion of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway in 188 5. During this period, it is apparent that certain sports facilitated a rapid expansion of activities when the railway brought thousands of new settlers to the province in the closing years of the century. -

Marketing Positive Fan Behavior at the Pennsylvania State University

Marketing Positive Fan Behavior at The Pennsylvania State University Presidential Leadership Academy Spring 2011 Researched, written and presented by: Sara Battikh, Angelo Cerimele, Sarah Dafilou, Bagas Dhanurendra, Sean Gillooly, Jared Marshall, Alyssa Wasserman and Sean Znachko I. Introduction The two questions that began the policy discussion were: who is this program made for and how can that information get to them? The Penn State fan base is made of a diverse group of people: from freshman to seniors, recent graduates to ―I’ve never missed a game in 60 years‖ alumni, from college friends visiting their peers, to parents visiting their children in addition to the fans of the visiting team. There are hundreds of thousands of sports fans that come to Penn State each weekend to support their teams. But are they supporting their team in the right way? Is making racial slurs towards a couple being a good Penn State fan? Is throwing beer cans at a visiting student from the other school being a good Penn State fan? In response to these incidents, fan behavior at Penn State needs to be addressed. This proposal comes in two parts. The first shows ways to promote what it means to be a good Penn State fans to the various audiences described above. The second part of the proposal is a marketing strategy for the text-a-tip program, a way to combat negative fan behavior that may occur at games. II. The Campaign to Promote Positive Fan Behavior The Slogan Improving fan behavior is an extremely broad topic; mostly due to the fact that Penn State's fan base is one of the largest in the world. -

One Last Call for 'Skeller'

Independently published by students at Penn State Vol. 118, No. 72 Tuesday, Dec. 5, 2017 Editor’s Note: To commemorate the final week of daily print publication, The Daily Collegian will be showcasing previous mastheads. Starting Jan. 8, 2018, we will publish on Mondays and Thursdays in print. Follow us on our website and on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and Instagram for daily coverage. INSIDE: One last call Halting pedestrian for ‘Skeller’ accidents By Aubree Rader THE DAILY COLLEGIAN After 85 years of serving State College residents and Penn State students, Rathskeller will soon close its doors for the final time. Sam Lauriello Spat’s Cafe, under the same owner Duke One Penn State class is helping to Gastiger, will also shut down, according to a release. stop pedestrian accidents. “It has been a great honor operating these two Page 2 iconic establishments and serving this community and its many truly wonderful patrons and friends,” Christopher Sanders/Collegian Gastiger said in a press release. “We are grateful Running Back Saquon Barkley (26) celebrates after defeating Michigan 43-13 at Beaver for the loyalty that people-- including our incred- Stadium on Oct. 21. ible employees-- Residents speak have shown us “It has been a great MY VIEW | JACK R. HIRSH over the years. out We most regret honor operating these closing with such two iconic short notice, but establishments and it was unavoid- serving this Barkley still the best able given the community and its timeline dictated many truly wonderful by the new prop- erty owners.” patrons and friends” in college football Closing dates for both places Duke Gastiger Saquon Barkley was the best player in 180 yards per game, well behind leader have yet to be Owner determined, and Collegian file photo college football this past season. -

Race and College Football in the Southwest, 1947-1976

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2014 DESEGREGATING THE LINE OF SCRIMMAGE: RACE AND COLLEGE FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST, 1947-1976 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ____________________________ Dr. Stephen H. Norwood, Chair ____________________________ Dr. Robert L. Griswold ____________________________ Dr. Ben Keppel ____________________________ Dr. Paul A. Gilje ____________________________ Dr. Ralph R. Hamerla © Copyright by CHRISTOPHER R. DAVIS 2014 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements In many ways, this dissertation represents the culmination of a lifelong passion for both sports and history. One of my most vivid early childhood memories comes from the fall of 1972 when, as a five year-old, I was reading the sports section of one of the Dallas newspapers at my grandparents’ breakfast table. I am not sure how much I comprehended, but one fact leaped clearly from the page—Nebraska had defeated Army by the seemingly incredible score of 77-7. Wild thoughts raced through my young mind. How could one team score so many points? How could they so thoroughly dominate an opponent? Just how bad was this Army outfit? How many touchdowns did it take to score seventy-seven points? I did not realize it at the time, but that was the day when I first understood concretely the concepts of multiplication and division. Nebraska scored eleven touchdowns I calculated (probably with some help from my grandfather) and my love of football and the sports page only grew from there. -

Auburn Vs Clemson (10/27/1962)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1962 Auburn vs Clemson (10/27/1962) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Auburn vs Clemson (10/27/1962)" (1962). Football Programs. 56. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/56 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLEMSON MEMORIAL 5TA0IUM-2RM. CLEMSON OCT -27/ AUBURN OFFICIAL PR.OO'RAM 50<t= 7 Thru-Liners Daily FOR SAFETY - CONVENIENCE As Follows: Via Atlanta. Ga. To Houston Texas Via Atlanta to COMFORT AND ECONOMY Jackson, Miss. Via Atlanta to Tallahassee, Fla. Via Atlanta to Dallas, Texas Via Atlanta to Wichita Falls. Texas Via Atlanta to Texarkana, Texas Via Atlanta to New Orleans, La. Three Thru -Lines Daily to Norfolk, Va. & Two Trips Daily to Columbia and Myrtle Beach & Seven Thru Trips AIR- SUSPENSION Daily to Charlotte, N. C. (Thru-Liners) Six Trips Daily to TRAILWAYS COACHES New York City (Three Thru-Liners) Three Thru-Liners Daily To Cleveland, Ohio* fe You board and leave your . -

Bridging the Gap: Raising Global Awareness at Penn State Oren

Bridging the Gap: Raising Global Awareness at Penn State Presidential Leadership Academy Spring 2014 Oren Adam, Briana Adams, Stephanie Metzger, Esther Park Presidential Leadership Academy Table of Contents I. Problem Identification………..1 II. Global Environment………..7 A. Global Landmarks………..7 B. First Year Seminar………..8 C. Global Learning……….11 D. Global Ambassadors………..13 E. International Student Module………..16 III. Needs Assessment……….. 18 IV. Conclusion……….. 25 V. Citations……….. 28 “ATTRACTING INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS IS JUST ONE OF THE WAYS THAT WE CONTINUE TO STRENGTHEN OUR WORLDWIDE REACH. WE ARE LIVING AND WORKING IN AN INCREASINGLY GLOBALIZED WORLD, WHERE INTERNATIONAL COMPETENCY AND COLLABORATION ARE ESSENTIAL. WE ARE COMMITTED TO HELPING OUR STUDENTS PREPARE FOR THE NEW GLOBAL ECONOMY AND ALSO IN SERVING THE WORLD THROUGH OUR RESEARCH, TEACHING, AND SERVICE.” - OUTGOING PRESIDENT RODNEY ERICKSON Problem Identification In line with recent trends, Penn State is becoming increasingly globalized, with the help of international students. In the fall of 2012, Penn State enrolled on its main campus 6,786 international students, representing 131 countries (Penn State Admission Statistics). According to the latest numbers from the International Education’s “Open Doors” report, this makes Penn State –and more specifically, its University Park campus– the institution with the tenth highest number of international student enrollment in the United States, and first in Pennsylvania. These figures reflect the efforts of the administration to enrich the university through diversity, as evidenced by Penn State’s outgoing president Rodney Erickson’s statement: “Attracting international students is just one of the ways that we continue to strengthen our worldwide reach. We are living and working in an increasingly globalized world, where international competency and collaboration are essential. -

Penalties for Hospital Acquired Conditions

Penalties For Hospital Acquired Infections Kaiser Health News Penalties For Hospital Acquired Conditions Medicare is penalizing hospitals with high rates of potentially avoidable mistakes that can harm patients, known as "hospital-acquired conditions." Penalized hospitals will have their Medicare payments reduced by 1 percent over the fiscal year that runs from October 2014 through September 2015. To determine penalties, Medicare ranked hospitals on a score of 1 to 10, with 10 being the worst, for three types of HACs. One is central-line associated bloodstream infections, or CLABSIs. The second if catheter- associated urinary tract infections, or CAUTIs. The final one, Serious Complications, is based on eight types of injuries, including blood clots, bed sores and falls. Hospitals with a Total HAC Score above 7 will be penalized. Source: Centers For Medicare & Medicaid Services Serious Compli Total Provider cations CLABSI HAC ID Hospital City State County Score Score CAUTI Score Score Penalty 20017 Alaska Regional Hospital Anchorage AK Anchorage 7 9 10 8.625 Penalty 20001 Providence Alaska Medical Center Anchorage AK Anchorage 10 9 6 8.375 Penalty 20027 Mt Edgecumbe Hospital Sitka AK Sitka 7 Not Available Not Available 7 No Penalty 20006 Mat-Su Regional Medical Center Palmer AK Matanuska Susitna 10 6 3 6.425 No Penalty 20012 Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Fairbanks AK Fairbanks North Star 9 8 1 6.075 No Penalty 20018 Yukon Kuskokwim Delta Reg Hospital Bethel AK Bethel 6 Not Available Not Available 6 No Penalty 20024 Central Peninsula General -

Glenn Killinger, Service Football, and the Birth

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Humanities WAR SEASONS: GLENN KILLINGER, SERVICE FOOTBALL, AND THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN HERO IN POSTWAR AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation in American Studies by Todd M. Mealy © 2018 Todd M. Mealy Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2018 ii This dissertation of Todd M. Mealy was reviewed and approved by the following: Charles P. Kupfer Associate Professor of American Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Simon Bronner Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Studies and Folklore Raffy Luquis Associate Professor of Health Education, Behavioral Science and Educaiton Program Peter Kareithi Special Member, Associate Professor of Communications, The Pennsylvania State University John Haddad Professor of American Studies and Chair, American Studies Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Glenn Killinger’s career as a three-sport star at Penn State. The thrills and fascinations of his athletic exploits were chronicled by the mass media beginning in 1917 through the 1920s in a way that addressed the central themes of the mythic Great American Novel. Killinger’s personal and public life matched the cultural medley that defined the nation in the first quarter of the twentieth-century. His life plays outs as if it were a Horatio Alger novel, as the anxieties over turn-of-the- century immigration and urbanization, the uncertainty of commercializing formerly amateur sports, social unrest that challenged the status quo, and the resiliency of the individual confronting challenges of World War I, sport, and social alienation. -

Sept. 10-12, 2018

Vol. 119, No. 7 Sept. 10-12, 2018 REFLECTIONS Seventeen years after the attacks on 9/11 — Shanksville remembers By Tina Locurto that day, but incredible good came out in response,” Barnett said THE DAILY COLLEGIAN with a smile. Shanksville is a small, rural town settled in southwestern Heroes in flight Pennsylvania with a population of about 237 people. It has a general Les Orlidge was born and raised in Shanksville. But, his own store, a few churches, a volunteer fire department and a school dis- memories of Sept. 11 were forged from over 290 miles away. trict. American flags gently hang from porch to porch along streets A Penn State alumnus who graduated in 1977, Orlidge had a short with cracked pavement. stint with AlliedSignal in Teterboro, New Jersey. From the second It’s a quiet, sleepy town. floor of his company’s building, he witnessed the World Trade Cen- It’s also the site of a plane crash that killed 40 passengers and ter collapse. crew members — part of what would become the deadliest attack “I watched the tower collapse — I watched the plane hit the on U.S. soil. second tower from that window,” Orlidge said. “I was actually de- The flight, which hit the earth at 563 mph at a 40 degree angle, left pressed for about a year.” a crater 30-feet wide and 15-feet deep in a field in the small town of Using a tiny AM radio to listen for news updates, he heard a re- Shanksville. port from Pittsburgh that a plane had crashed six miles away from Most people have a memory of where they were during the at- Somerset Airport. -

Penn State Faculty and Staff Contribution Form

Penn State Faculty and Staff Contribution Fo rm Dr./Ms. Mrs./Mr. Name: First Middle Last Unit/College/Campus Home Address Campus Address City City State Zip Title Email I am a Penn State graduate, class of Home Phone If alumna and married, please enter your name before marriage if Penn State ID Number different from your present name Gift Designations See suggestions on reverse Enter the designation(s) for your gift and the portion of your gift that each should receive. (Please make sure the individual gift amounts equal your total gift.) 1._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* 2._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* 3._________________________________________________________________________________________________ $____________ .00 Designation (Please specify location if other than University Park Campus) Amount per pay period* Total (all designations/pay period) ............................................................................................................................... $____________ .00 Total per pay period *Amount per pay period if payroll deduction, otherwise total of gift per designation Three Ways to Make a Gift I Payroll deduction I a new payroll deduction donor Effective