(1992) Yeats, Bloom and the Dialectics of Theory, Criticism and Poetry. Phd Thesis, University of Nottingham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of Its Time”

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of its Time” JANUARY 1995 page 1 stepped in. When we stepped out at the Second floor we found three others, including Pauline Scarf, already waiting in the room. The other THE EDITORIAL SLANT lift hadn’t arrived. I took off my coat, unpacked my bags of tea-bags, coffee, sugar, cups, biscuits, FSS info sheets and other junk materials I had brought, then set about, with the others, setting up the room. At that point those from the other lift arrived - coming down in the second lift. by Ron Clarke They had overloaded the first lift. However the FSS Information Officer was not with them - Anne descended five minutes later in another lift. After helping set up the chairs in the room in a circle, I gave a quick run- down on the topic of discussion for the night - “Humour In SF” and asked who wanted to start. After a short dead silence, I read out short items from the Humour In SF section from the ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION and the meeting got into first gear. The meeting then There used to be a Futurian Society in New York. There used discussed what each attendee thought of humour in SF and gave to be a Futurian Society in Sydney. The New York Futurian Society is comments on the books they had brought illustrating their thoughts or long gone - the Futurian Society of Sydney lives again. what they had read. Those attending the meeting were Mark When I placed the advertisements in 9 TO 5 Magazine, gave Phillips, Graham Stone, Ian Woolf, Peter Eisler, Isaac Isgro, Wayne pamphlets to Kevin Dillon to place in bookshops and puts ads in Turner, Pauline Scarf, Ken Macaulay, Kevin Dillon, Anne Stewart, Gary GALAXY bookshop I wasn’t sure how many sf readers would turn up Luckman and myself. -

Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020

Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 1 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 __________________________________________________________________ Editor: Dr. Erik Juergensmeyer Fort Lewis College Special Issue: The Public Humanities, Post-Hurricane Harvey __________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents ARTICLES Introduction: The Public Humanities, Post-Harvey John C. Mulligan ….………………………..…………….…………….……………….………...4 Hydrological Citizenship after Hurricane Harvey Kevin MacDonnell ……………………………………………………..………………………..……………………18 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 2 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Shared Vulnerability: Rethinking Human and Non-human Bodies in Disasters Lesli Vollrath ……………………………………………………………………………………32 The Theatre of Climate Change; or, Mold Humanities Joe T. Carson……………………………………………………………………………….……45 The Art of Living with Our Damaged Planet Marley Foster ………………………………………………………………………….………...60 Future-Facing Folklore Joshua Gottlieb-Miller ……...............…………………………………………………………………………….….......75 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 3 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 Introduction: The Public Humanities, Post-Harvey Author: John C. Mulligan Title: PhD Affiliation: Rice University Location: Houston, TX Email: [email protected] Keywords: Public Humanities, Critical Animal Studies, Biopolitics Abstract This essay introduces -

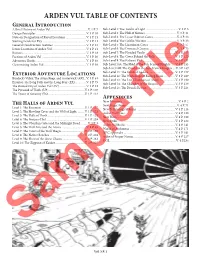

ARDEN VUL TABLE of CONTENTS General Introduction a Brief History of Arden Vul

ARDEN VUL TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction A Brief History of Arden Vul ..................................................V. 1 P. 7 Sub-Level 1: The Tombs of Light ...........................................V. 3 P. 3 Design Principles ...................................................................V. 1 P. 10 Sub-Level 2: The Hall of Shrines ..........................................V. 3 P. 11 Note on Designation of Keyed Locations ...........................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 3: The Lesser Baboon Caves ...............................V. 3 P. 23 Starting Levels for PCs ..........................................................V. 1 P. 11 Sub-Level 4: The Goblin Warrens........................................ V. 3 P. 33 General Construction Features ...........................................V. 1 P. 12 Sub-Level 5: The Lizardman Caves .....................................V. 3 P. 57 Iconic Locations of Arden Vul .............................................V. 1 P. 14 Sub-Level 6: The Drowned Canyon ....................................V. 3 P. 73 Rumors ....................................................................................V. 1 P. 18 Sub-Level 7: The Flooded Vaults .......................................V. 3 P. 117 Factions of Arden Vul ...........................................................V. 1 P. 30 Sub-Level 8: The Caves Behind the Falls ..........................V. 3 P. 125 Adventure Hooks ...................................................................V. 1 P. 48 Sub-Level 9: The Kaliyani Pits ...........................................V. -

FY2009 Annual Listing

2008 2009 Annual Listing Exhibitions PUBLICATIONS Acquisitions GIFTS TO THE ANNUAL FUND Membership SPECIAL PROJECTS Donors to the Collection 2008 2009 Exhibitions at MoMA Installation view of Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at The Museum of Modern Art, 2008. Courtesy the artist, Luhring Augustine, New York, and Hauser & Wirth Zürich London. Photo © Frederick Charles, fcharles.com Exhibitions at MoMA Book/Shelf Bernd and Hilla Becher: Home Delivery: Fabricating the Through July 7, 2008 Landscape/Typology Modern Dwelling Organized by Christophe Cherix, Through August 25, 2008 July 20–October 20, 2008 Curator, Department of Prints Organized by Peter Galassi, Chief Organized by Barry Bergdoll, The and Illustrated Books. Curator of Photography. Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Peter Glossolalia: Languages of Drawing Dalí: Painting and Film Christensen, Curatorial Assistant, Through July 7, 2008 Through September 15, 2008 Department of Architecture and Organized by Connie Butler, Organized by Jodi Hauptman, Design. The Robert Lehman Foundation Curator, Department of Drawings. Chief Curator of Drawings. Young Architects Program 2008 Jazz Score July 20–October 20, 2008 Multiplex: Directions in Art, Through September 17, 2008 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, 1970 to Now Organized by Ron Magliozzi, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Assistant Curator, and Joshua Design. Organized by Deborah Wye, Siegel, Associate Curator, The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Department of Film. Dreamland: Architectural Chief Curator of Prints and Experiments since the 1970s Illustrated Books. George Lois: The Esquire Covers July 23, 2008–March 16, 2009 Through March 31, 2009 Organized by Andres Lepik, Curator, Projects 87: Sigalit Landau Organized by Christian Larsen, Department of Architecture and Through July 28, 2008 Curatorial Assistant, Research Design. -

Cardano.BM - Logging, Benchmarking and Monitoring

Cardano.BM - logging, benchmarking and monitoring Alexander Diemand Denis Shevchenko Andreas Triantafyllos August 2019 Abstract This framework combines logging, benchmarking and monitoring. Complex evaluations of STM or monadic actions can be observed from outside while reading operating system coun- ters before and after, and calculating their differences, thus relating resource usage to such actions. Through interactive configuration, the runtime behaviour of logging or the measurement of resource usage can be altered. Further reduction in logging can be achieved by redirecting log messages to an aggrega- tion function which will output the running statistics with less frequency than the original message. Contents 1 Logging, benchmarking and monitoring 3 1.1 Main concepts ......................................3 1.1.1 LogObject ....................................3 1.1.2 Trace .......................................3 1.1.3 Backend .....................................4 1.1.4 Configuration ..................................4 1.2 Overview .........................................5 1.2.1 Backends .....................................5 1.2.2 Trace .......................................5 1.2.3 Monitoring ....................................5 1.2.4 IMPORTANT! ..................................5 1.3 Requirements ......................................6 1.3.1 Observables ...................................6 1.3.2 Traces .......................................7 1.3.3 Aggregation ...................................8 1.3.4 Monitoring ....................................8 -

Filozofické Aspekty Technologií V Komediálním Sci-Fi Seriálu Červený Trpaslík

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie interaktivních médií Dominik Zaplatílek Bakalářská diplomová práce Filozofické aspekty technologií v komediálním sci-fi seriálu Červený trpaslík Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Martin Flašar, Ph.D. 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval samostatně a použil jsem literárních a dalších pramenů a informací, které cituji a uvádím v seznamu použité literatury a zdrojů informací. V Brně dne ....................................... Dominik Zaplatílek Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat panu PhDr. Martinu Flašarovi, Ph.D za odborné vedení této bakalářské práce a podnětné a cenné připomínky, které pomohly usměrnit tuto práci. Obsah Úvod ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Seriál Červený trpaslík ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Vyobrazené technologie ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Android Kryton ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1. Teologická námitka ........................................................................................................ 15 2.1.2. Argument z vědomí ....................................................................................................... 18 2.1.3. Argument z -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

RAR AVANT LAFT 30.Pdf

, . ' " \ \ . " .;~' I , , . .' ' , , . , ~ . •I ". thellaocutsthehea r th e II d Eta SO c ~ ! a d h ~ ~ e a ~ f f 1 s h t he h e ~ e e at t II f st h 1 s h. e 1 0 t he f h 1 ~ ~ rOilo II s f c i 1o the a wt er sa1tdis01veswate chsifehthsifehts theskeletonismad k sa 1 td i c the a te s ke 1 e i IS ve s ~ a tOe ~ is Om a fnd ! r d 1 S 0 0 v b on .ee 0 t lsa e 1 1 :1 m e e ge n er t i 0 i R~ IV I at e t sm I a n Os:: l Pt a r S 0 i n 110 t I ~ ian d oe s i 2 g 1 W i a l s ~ I °t ex i st 0 S i:1 i s p e i f c ratsesopposniatn humanbonesinmoti noitomnoitomseta ~ n b 0 h n um a °rn ~ t e. s in II 0 ~ 8 n b ~ r 0 ~ } i ~ e an e ~ 1 n ds ta nay ~ d a II a W n :1 n i r g r wex~ f e rv at. ~ w c 01 e d r:1 s a neergninamadnat1 Paul Adams deified. cornea a sepraTe stlnGiNstEnch Tha instruments reDeD gR aSs is CrIKTs pRaYnG bIggUm HUmm bUZ z saW heAd (imaginary jewels) CL Champion Thomas Wiloch YARMULKE one of the kitchen travellers, his mouth was probably too hard, of course as a drunk, words felt too big in his mouth scissored vital his pits to remain below the horizon nearby a chicadee on this side raised one finger the uncontrollable saluted tedders-- He began to cast longing glances at the couch suddenly his orange squashing fingers sank, a short floor already gone all night he yanked the damn thing's fang, he got the jack, then nailed it to the cabinet, driven into his bib most of all his good cat was out walking like a dog Raff Lapgear I gcaatto IG 1 swaibsieo IG 5 Qualm. -

The Metaphysical Possibility of Time Travel Fictions Effingham, Nikk

University of Birmingham The metaphysical possibility of time travel fictions Effingham, Nikk DOI: 10.1007/s10670-021-00403-y License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Effingham, N 2021, 'The metaphysical possibility of time travel fictions', Erkenntnis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-021-00403-y Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell

Falling in love with “Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell It was around 2003 or 2004 when I fell in love with the British sci-fi comedy show “Red Dwarf”. I had been somewhat aware of the series when it launched in 1988 but the external model shots looked so unrealistic that I didn’t bother to try it… what a mistake! My epiphany came late one night after a long session of distance-studying for a degree with the Open University. Feeling very tired and just looking for something to relax with before going to bed, I was suddenly confronted with one of the funniest comedy scenes I had ever seen. That scene was in the Season VIII episode ‘Back in the Red, part 2’. I tuned in just at the moment that Rimmer was using a hammer to test the anaesthetic that he’d applied to his nether regions. I didn’t know the character or the back story that had brought him to that moment, but Chris Barrie’s wonderful acting sucked me in – I was laughing out loud and had suddenly become ‘a Dwarfer’. With one exception, I have loved every series of Red Dwarf, and in this blog I’ll be reflecting on what has made me come to love it so much over the 12 series that have been broadcast to date. For anyone was hasn’t seen Red Dwarf (and if you haven’t, get out there and find a copy now – seriously), the story begins with three of the series’ main characters who have either survived, or are descended from, a radiation accident that occurred three million years ago and killed all of the rest of the crew of the Jupiter Mining Corp ship ‘Red Dwarf’.