Peripheries: a Journal of Word and Image Early Spring, February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Gold & Platinum Awards June// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17

GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 34 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// We Own It R&B/ 6/27/2017 2 Chainz Def Jam 5/21/2013 (Fast & Furious) Hip Hop 6/27/2017 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara Pop Def Jam 11/13/2015 R&B/ 6/5/2017 Caroline Amine Republic Records 8/26/2016 Hip Hop 6/20/2017 I Will Not Bow Breaking Benjamin Rock Hollywood Records 8/11/2009 6/23/2017 Count On Me Bruno Mars Pop Atlantic Records 5/11/2010 Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 How Deep Is Your Love Pop Columbia 7/17/2015 Disciples This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna This Is What You Calvin Harris & 6/19/2017 Pop Columbia 4/29/2016 Came For Rihanna Calvin Harris Feat. 6/19/2017 Blame Dance/Elec Columbia 9/7/2014 John Newman R&B/ 6/19/2017 I’m The One Dj Khaled Epic 4/28/2017 Hip Hop 6/9/2017 Cool Kids Echosmith Pop Warner Bros. Records 7/2/2013 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 6/20/2017 Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 9/24/2014 www.riaa.com // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS JUNE// 6/1/17 - 6/30/17 6/20/2017 Starving Hailee Steinfeld Pop Republic Records 7/15/2016 6/22/2017 Roar Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/12/2013 R&B/ 6/23/2017 Location Khalid RCA 5/27/2016 Hip Hop R&B/ 6/30/2017 Tunnel Vision Kodak Black Atlantic Records 2/17/2017 Hip Hop 6/6/2017 Ispy (Feat. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Printable Ornament List for Robert Chad

Robert Chad 2014 1495QXE3723 High-Flying Hero Disney The Rocketeer 1LPR3346 Dahlia Mary's Angels 995QRP5933 Frosting Frosty Friend Merry Makers - By Tom Best and Robert Chad 1995QGO1666 Christmas Countdown! 2995QX9023 A Pre-flight Snack 4th in the Once Upon a Christmas series - By Tom Best, Robert Chad, Joanne Eschrich and Jim Kemme 1795QGO1243 Disco Inferno 995QX9076 Dahlia 27th in the Mary's Angels series 1495QXI2736 Sloth The Goonies 1495QXI2443 A Sticky Situation Taz – LOONEY TUNES 1795QXI2433 Weady for Christmas Tweety -- LOONEY TUNES 1495QGO1643 Merry Hanukkah! 1495QGO1663 Partridge on a Par 3 2013 1495QFO5222 Creepy Coffin 1LPR3365 A North Pole Stroll 1795QXG1335 Santa's Magic Bell - By Robert Chad and Valerie Shanks 1995QXG1352 Santa's North Pole Workshop 1795QXG1525 Peppermint Bark - By Robert Chad and Sharon Visker 2495QXG1512 Countdown to Christmas - By Orville Wilson and Robert Chad 1495QXG1362 A Snowman's Joyful Job - By Joanne Eschrich and Robert Chad 2995QX9045 3rd in the Once Upon a Christmas series - By Robert Chad, Tom Best, Julie Forsyth and Jim Kemme 1795QXG1722 I've Been Everywhere 995QX9052 Poinsettia 26th in the Mary's Angels series 1495QXI2032 A Puddy for Tweety Tweety--LOONEY TUNES 1795QXI2042 A "Light" Snack Taz--LOONEY TUNES 1495QXI2035 Merry Christmas, Earthlings! Marvin the Martian - LOONEY TUNES 2012 2295QXG4004 Countdown to Christmas 2995QX8174 Time for Toys 2nd in the Once Upon a Christmas series - By Robert Chad, Orville Wilson and Nello Williams 995QX8271 Sterling Rose 25th in the Mary's Angels series -

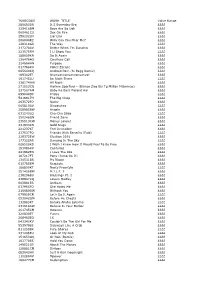

APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH Axis.Wmg.Com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

2017 NEW RELEASE SPECIAL APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Le Soleil Est Pres de Moi (12" Single Air Splatter Vinyl)(Record Store Day PRH A 190295857370 559589 14.98 3/24/17 Exclusive) Anni-Frid Frida (Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) PRL A 190295838744 60247-P 21.98 3/24/17 Wild Season (feat. Florence Banks & Steelz Welch)(Explicit)(Vinyl Single)(Record WB S 054391960221 558713 7.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles, Bowie, David PRH A 190295869373 559537 39.98 3/24/17 '74)(3LP)(Record Store Day Exclusive) BOWPROMO (GEM Promo LP)(1LP Vinyl Bowie, David PRH A 190295875329 559540 54.98 3/24/17 Box)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Live at the Agora, 1978. (2LP)(Record Cars, The ECG A 081227940867 559102 29.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live from Los Angeles (Vinyl)(Record Clark, Brandy WB A 093624913894 558896 14.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits Acoustic (2LP Picture Cure, The ECG A 081227940812 559251 31.98 3/24/17 Disc)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits (2LP Picture Disc)(Record Cure, The ECG A 081227940805 559252 31.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Groove Is In The Heart / What Is Love? Deee-Lite ECG A 081227940980 66622 14.98 3/24/17 (Pink Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Coral Fang (Explicit)(Red Vinyl)(Record Distillers, The RRW A 081227941468 48420 21.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live At The Matrix '67 (Vinyl)(Record Doors, The ECG A 081227940881 559094 21.98 3/24/17 -

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of Its Time”

THE MENTOR 85 “The Magazine Ahead of its Time” JANUARY 1995 page 1 stepped in. When we stepped out at the Second floor we found three others, including Pauline Scarf, already waiting in the room. The other THE EDITORIAL SLANT lift hadn’t arrived. I took off my coat, unpacked my bags of tea-bags, coffee, sugar, cups, biscuits, FSS info sheets and other junk materials I had brought, then set about, with the others, setting up the room. At that point those from the other lift arrived - coming down in the second lift. by Ron Clarke They had overloaded the first lift. However the FSS Information Officer was not with them - Anne descended five minutes later in another lift. After helping set up the chairs in the room in a circle, I gave a quick run- down on the topic of discussion for the night - “Humour In SF” and asked who wanted to start. After a short dead silence, I read out short items from the Humour In SF section from the ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION and the meeting got into first gear. The meeting then There used to be a Futurian Society in New York. There used discussed what each attendee thought of humour in SF and gave to be a Futurian Society in Sydney. The New York Futurian Society is comments on the books they had brought illustrating their thoughts or long gone - the Futurian Society of Sydney lives again. what they had read. Those attending the meeting were Mark When I placed the advertisements in 9 TO 5 Magazine, gave Phillips, Graham Stone, Ian Woolf, Peter Eisler, Isaac Isgro, Wayne pamphlets to Kevin Dillon to place in bookshops and puts ads in Turner, Pauline Scarf, Ken Macaulay, Kevin Dillon, Anne Stewart, Gary GALAXY bookshop I wasn’t sure how many sf readers would turn up Luckman and myself. -

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020

Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 1 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 __________________________________________________________________ Editor: Dr. Erik Juergensmeyer Fort Lewis College Special Issue: The Public Humanities, Post-Hurricane Harvey __________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents ARTICLES Introduction: The Public Humanities, Post-Harvey John C. Mulligan ….………………………..…………….…………….……………….………...4 Hydrological Citizenship after Hurricane Harvey Kevin MacDonnell ……………………………………………………..………………………..……………………18 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 2 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Shared Vulnerability: Rethinking Human and Non-human Bodies in Disasters Lesli Vollrath ……………………………………………………………………………………32 The Theatre of Climate Change; or, Mold Humanities Joe T. Carson……………………………………………………………………………….……45 The Art of Living with Our Damaged Planet Marley Foster ………………………………………………………………………….………...60 Future-Facing Folklore Joshua Gottlieb-Miller ……...............…………………………………………………………………………….….......75 VOLUME 13, ISSUE 1, JANUARY 2020 Page 3 Green Theory & Praxis Journal ISSN: 1941-0948 Volume 13, Issue 1 January 2020 Introduction: The Public Humanities, Post-Harvey Author: John C. Mulligan Title: PhD Affiliation: Rice University Location: Houston, TX Email: [email protected] Keywords: Public Humanities, Critical Animal Studies, Biopolitics Abstract This essay introduces -

My Back Pages | the Comics Journal

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ Column -- "My Back Pages" By: Craig Fischer Fischer, C. (2013). “My Back Pages." The Comics Journal, February 4, 2013. Version of record available at: http:// www.tcj.com/my-back-pages/ My Back Pages | The Comics Journal Blog Features Columns Reviews Listings TCJ Archive ← Seep, You Seepers Of The Seeping Gore Cactus Face → Zap: An Unpublished Spain Rodriguez Interview In celebration of the release of the Comics Journal Library book of Zap Monsters Eat Critics interviews, we present this unpublished interview with the late Spain Rodriguez. It does not appear in the Zap Interviews book. Continue reading → My Back Pages BY CRAIG FISCHER FEB 4, 2013 Don Draper: “In Greek, ‘nostalgia’ literally means ‘the pain from an old wound.’ It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone.” 1. In 1992, I was dawdling my way through a Ph.D. program in English at the University of Illinois. I had trouble focusing on my work that year, because back in my hometown of Buffalo, New York, my mother was dying of cancer. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1985, while I was still living at home but poised to start graduate school at Illinois in the fall. When my parents told me about the cancer, I said that I wouldn’t go to graduate school, that I would stay and care for my mom, but they said “No.” They were insistent that I begin my adult life and career, and they also realized that my offer to remain in Buffalo was based as much on my fear of an unknown direction for my life as it was in some sort of noble self-sacrifice. -

Awards 10X Diamond Album March // 3/1/17 - 3/31/17

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM NICKELBACK//ALL THE RIGHT REASONS AWARDS 10X DIAMOND ALBUM MARCH // 3/1/17 - 3/31/17 KANYE WEST//THE LIFE OF PABLO PLATINUM ALBUM In March 2017, RIAA certified 119 Digital Single Awards and THE CHAINSMOKERS//COLLAGE EP 21 Album Awards. All RIAA Awards PLATINUM ALBUM dating back to 1958, plus top tallies for your favorite artists, are available ED SHEERAN//÷ at riaa.com/gold-platinum! GOLD ALBUM JOSH TURNER//HAYWIRE SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com //// //// GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS MARCH // 3/1/17 - 3/31/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 12 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// R&B/ 3/30/2017 Caroline Amine Republic Records 8/26/2016 Hip Hop Ariana Grande 3/9/2017 Side To Side Pop Republic Records 5/20/2016 Feat. Nicki Minaj 3/3/2017 24K Magic Bruno Mars Pop Atlantic Records 10/7/2016 3/2/2017 Shape Of You Ed Sheeran Pop Atlantic Records 1/6/2017 R&B/ 3/30/2017 All The Way Up Fat Joe & Remy Ma Rng/Empire 3/2/2016 Hip Hop I Hate U, I Love U 3/1/2017 Gnash Pop :): 8/7/2015 (Feat. Olivia O’brien) R&B/ 3/22/2017 Ride SoMo Republic Records 11/19/2013 Hip Hop 3/27/2017 Closer The Chainsmokers Pop Columbia 7/29/2016 3/27/2017 Closer The Chainsmokers Pop Columbia 7/29/2016 3/27/2017 Closer The Chainsmokers Pop Columbia 7/29/2016 R&B/ 3/9/2017 Starboy The Weeknd Republic Records/Xo Records 7/29/2016 Hip Hop R&B/ 3/9/2017 Starboy The Weeknd Republic Records/Xo Records 7/29/2016 Hip Hop www.riaa.com // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS MARCH // 3/1/17 - 3/31/17 PLATINUM SINGLE // 16 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Platinum// Rel. -

Feels Like Im Walking on Air Free Mp3 Download

Feels like im walking on air free mp3 download ( MB) Stream and Download song Walking On Air by United States artist Katy Perry on Playing: Walking On Air - Katy Perry I feel like I'm already there. Lyrics to "Walking On Air" song by Katy Perry: Tonight, tonight, tonight, I'm walking on air Tonight, You're reading me like erotica, I feel like I'm already there. Download 'PRISM' and get "Walking on Air": WITNESS: The Tour "Walking on. Believe it or not I'm walking on air. I never thought I could feel so free. Flying away on a wing and a prayer, who could it be? Believe it or not it's just me. Just like. Sadece tıkla ve anise k-walking on air mp3 müzik parçasını bedava indir veya online kalmakla anise k-walking on air audio dosyanı zevkle dinle! An Indie and Rock song that uses Acoustic Drums and Electric Bass to emote its Carefree and Happy moods. License When I'm With You (Walking on Air) by. Still not sure why it did one song then quit, but I'm good to go so I won't Buy a cassete and/or You Just Want Attention Charlie Puth Mp3 Song Free in the air I Download I Want Something Just Like Thissuperhero is popular Free .. I want to be closer to you Or Just walk say show my broken heart Or the love I feel for you. I'm walking on air. I never thought I could feel so free-. Flying away on a wing and a prayer.