Hakansson SEEING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

User Guide 2.0

NORTH CELESTIAL POLE Polaris SUN NORTH POLE E Q U A T O R C SOUTH POLE E L R E S T I A L E Q U A T O EARTH’S AXIS EARTH’S SOUTH CELESTIAL POLE USER GUIDE 2.0 WITH AN INTRODUCTION 23.45° TO THE MOTIONS OF THE SKY meridian E horizon W rise set Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics 2019 II III Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics FULLSCREEN CONTENTS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS VI SKY SETTINGS 24 CONSTELLATIONS 24 HELP MENU INTRODUCTION 1 ZODIAC 24 BASIC CONCEPTS 2 CONSTELLATION NAMES 24 CENTRED ON EARTH 2 WORLD CLOCKASTRONOMYASTROLOGY MINIMAL STAR NAMES 25 SEARCH LOCATIONS THE CELESTIAL SPHERE IS LONG EXPOSURE 25 A PROJECTION 2 00:00 INTERSTELLAR GAS & DUST 25 A FIRST TOUR 3 EVENTS & SKY GRADIENT 25 PRESETS NOTIFICATIONS LOOK AROUND, ZOOM IN AND OUT 3 GUIDES 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS ON THE GLOBE 4 HORIZON 26 CENTER YOUR VIEW 4 SKY EARTH SOLAR PLANET NAMES 26 SYSTEM ABOUT & INFO FULLSCREEN 4 CONNECTIONS 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 5 CELESTIAL RINGS 27 ADVANCED SETTINGS FAVOURITES 5 EQUATORIAL COORDINATES 27 QUICK START QUICK VIEW OPTIONS 6 FAVOURITE LOCATIONS ORBITS 27 VIEW THE USER INTERFACE 7 EARTH SETTINGS 28 GEOCENTRIC HOW TO EXIT 7 CLOUDS 28 SCREENSHOT PRESETS 8 HI -RES 28 POSITION 28 HELIOCENTRIC WORLD CLOCK 9 COMPASS CELESTIAL SPHERE SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 10 THE MOON 29 FAVOURITES 10 EVENTS & NOTIFICATIONS 30 ASTRONOMY MODE 15 SETTINGS 31 VISUAL SETTINGS ASTROLOGY MODE 16 SYSTEM NOTIFICATIONS 31 IN APP NOTIFICATIONS 31 MINIMAL MODE 17 ABOUT 32 THE VIEWS 18 ADVANCED SETTINGS 32 SKY VIEW 18 COMPASS ON / OFF 19 ASTRONOMICAL ALGORITHMS 33 EARTH VIEW 20 SCREENSHOT 34 CELESTIAL SPHERE ON / OFF 20 HELP 35 TIME CONTROL SOLAR SYSTEM VIEW 21 FINAL THOUGHTS 35 GEOCENTRIC / HELIOCENTRIC 21 TROUBLESHOOTING 36 VISUAL SETTINGS 22 CONTACT 37 CLOCK SETTINGS 22 ASTRONOMICAL CONCEPTS 38 ECLIPTIC CLOCK FACE 22 EQUATORIAL CLOCK FACE 23 IV V INTRODUCTION SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS The Cosmic Watch is a virtual planetarium on your mobile device. -

Astronomical Estimation of the Dates Ciphered in the Egyptian Zodiacs: a Methodology

chapter 16 Astronomical estimation of the dates ciphered in the Egyptian zodiacs: a methodology 1. Thus, the pre-Copernican astronomy didn’t distin- SEVEN PLANETS OF THE ANTIQUITY. guish between the Sun, the Moon and the planets in ZODIACS AND HOROSCOPES their movement across the celestial sphere. It is possible that at dawn of astronomy people Nowadays we know seven planets – Jupiter, Saturn, had thought all seven luminaries that one sees on the Mars, Venus, Mercury, Uranus and Neptune. How- celestial sphere to move inside a real sphere of cyclo- ever, Uranus wasn’t known to ancient astronomy since pean proportions, with all the immobile stars affixed this planet is too dim for the naked eye to see. It was thereto in some way. After many years of observa- discovered by the English astronomer William Her- tion, ancient astronomers discovered that all these schel in 1781 – already in the telescope observation luminaries follow the same imaginary itinerary as epoch, that is ([85], Volume 33, page 168) – let alone they move along the celestial sphere. They realized Neptune. that this itinerary follows an extremely large circum- Therefore, ancient astronomers were familiar with ference upon a sphere and doesn’t change with the only five of the planets known to us today, Uranus and course of time (today we know that it does change, Neptune excluded. However, before the heliocentric but very slowly, and cannot be noticed with the naked theory of Copernicus became widespread, the Sun eye). The planetary itinerary on the celestial sphere and the Moon were ranked among planets as well. -

Download/Hc:27894/CONTENT/ How to Read Neanderthal for Sapiens.Pdf

DO THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ASTRONOMY AND RELIGION, BEGINNING IN PREHISTORY, FORM A DISTINCT RELIGIOUS TRADITION? by Brandon Reece Taylor (a.k.a. Brandon Taylorian / Cometan) A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Humanities, Language and Global Studies University of Central Lancashire In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts August 2020 Word count: 14,856 1 of 96 Abstract –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Astronomy and religion have long been intertwined with their interactions resembling a symbiotic relationship since prehistoric times. Building on existing archaeological research, this study asks: do the interactions between astronomy and religion, beginning from prehistory, form a distinct religious tradition? Prior research exploring the prehistoric origins of religion has unearthed evidence suggesting the influence of star worship and night sky observation in the development of religious sects, beliefs and practices. However, there does not yet exist a historiography dedicated to outlining why astronomy and religion mutually developed, nor has there been a proposal set forth asserting that these interactions constitute a religious tradition; proposed herein as the Astronic tradition, or Astronicism. This paper pursues the objective of arguing for the Astronic tradition to be treated, firstly, as a distinct religious tradition and secondly, as the oldest archaeologically-verifiable religious tradition. To achieve this, the study will adopt a multidisciplinary approach involving archaeology, anthropology, geography, psychology, mythology, archaeoastronomy and comparative religion. After proposing six characteristics inherent to a religious tradition, the paper will assemble a historiography for astronomical religion. As a consequence of the main objective, this study also asserts that astronomical religion, most likely astrolatry, has its origins in the Upper Palaeolithic period of the Stone Age based on specimens from the archaeological record. -

Stellar Theology and Masonic Astronomy

CONTENTS Forward Understanding Why This Book is Important by Jordan Maxwell: ........................... vii Part First Chapter 1 Introduction — A Few Words to the Masonic Fraternity ................................................. 2 Chapter 2 The Ancient Mysteries Described ....................... 6 Chapter 3 A Chapter of Astronomical Facts........................... 41 The Ecliptic .............................................................. 42 The Zodiac ............................................................... 42 Aries ......................................................................... 43 Taurus....................................................................... 43 Gemini ................................................................... 44 Cancer ...................................................................... 44 Leo .......................................................................... 45 Virgo......................................................................... 45 Libra ....................................................................... 46 Scorpio .................................................................. 46 Sagittarius .............................................................. 47 Capricornus .............................................................. 47 Aquarius and Pisces ................................................. 47 The Signs of the Zodiac ........................................... 47 The Solstitial Points .............................................. 50 The Equinoctial -

Planets Solar System Paper Contents

Planets Solar system paper Contents 1 Jupiter 1 1.1 Structure ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Composition ......................................... 1 1.1.2 Mass and size ......................................... 2 1.1.3 Internal structure ....................................... 2 1.2 Atmosphere .............................................. 3 1.2.1 Cloud layers ......................................... 3 1.2.2 Great Red Spot and other vortices .............................. 4 1.3 Planetary rings ............................................ 4 1.4 Magnetosphere ............................................ 5 1.5 Orbit and rotation ........................................... 5 1.6 Observation .............................................. 6 1.7 Research and exploration ....................................... 6 1.7.1 Pre-telescopic research .................................... 6 1.7.2 Ground-based telescope research ............................... 7 1.7.3 Radiotelescope research ................................... 8 1.7.4 Exploration with space probes ................................ 8 1.8 Moons ................................................. 9 1.8.1 Galilean moons ........................................ 10 1.8.2 Classification of moons .................................... 10 1.9 Interaction with the Solar System ................................... 10 1.9.1 Impacts ............................................ 11 1.10 Possibility of life ........................................... 12 1.11 Mythology ............................................. -

Bowditch on Cel

These are Chapters from Bowditch’s American Practical Navigator click a link to go to that chapter CELESTIAL NAVIGATION CHAPTER 15. NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY 225 CHAPTER 16. INSTRUMENTS FOR CELESTIAL NAVIGATION 273 CHAPTER 17. AZIMUTHS AND AMPLITUDES 283 CHAPTER 18. TIME 287 CHAPTER 19. THE ALMANACS 299 CHAPTER 20. SIGHT REDUCTION 307 School of Navigation www.starpath.com Starpath Electronic Bowditch CHAPTER 15 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS 1500. Definition ing principally with celestial coordinates, time, and the apparent motions of celestial bodies, is the branch of as- Astronomy predicts the future positions and motions tronomy most important to the navigator. The symbols of celestial bodies and seeks to understand and explain commonly recognized in navigational astronomy are their physical properties. Navigational astronomy, deal- given in Table 1500. Table 1500. Astronomical symbols. 225 226 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY 1501. The Celestial Sphere server at some distant point in space. When discussing the rising or setting of a body on a local horizon, we must locate Looking at the sky on a dark night, imagine that celes- the observer at a particular point on the earth because the tial bodies are located on the inner surface of a vast, earth- setting sun for one observer may be the rising sun for centered sphere. This model is useful since we are only in- another. terested in the relative positions and motions of celestial Motion on the celestial sphere results from the motions bodies on this imaginary surface. Understanding the con- in space of both the celestial body and the earth. Without cept of the celestial sphere is most important when special instruments, motions toward and away from the discussing sight reduction in Chapter 20. -

070256B0.Pdf

NATURE useful in districts remote from medical aid. Courses of Messrs. Slipher and Lalllpland, un the visibility of fine elementary lectures are also given, both at the college and lines a t various distances. The experiments were exactly similar to those previously carried out with a fine wire of at the United Service Institution, open to all who may 0.7 inch diameter, except that a fine blue line 0.7 inch in expect to reside or travel in the tropics. The" Year Book" width, drawn on a white disc 8 feet in diameter, was contains details of the college and its curriculum, and useful observed at the same time as the wire.· At a distance of directions for the preservation of health in the tropics. 1450 feet, when the angular width of the disc was 19' and that of the lines was 0".86, the wire was certainly IN the short notice of Mr. Cecil Hawkins's" Elementary seen, but a fi ctitious line was seen accompanying what was Geometry" in NATURE of June 30 (p. 193), reference was supposed to be the real one. The general results of the experiments indicated that the made to the absence of numerical answers in the copy wire was more generaiiv visible than the line, although at supplied. Mr. Hawkins asks us to state that the book is distances less than 400 feet the latter was the more readily also supplied with answers if desired. seen. MESSRS. T . C. AND E. C. JACK, of Edinburgh, have sub VARIABILITY OF MI I\ OR PLA:'(ETs.-Observa tions of the mitted for ollr inspection four of the pl ates of a stereoscopic magnitudes of the minor planets Iris, Ceres, and Pallas, m ade by H err J. -

2 Useful Astrobiological Data

2 Useful Astrobiological Data 2.1 Physical and Chemical Data 1. International System Units Name Symbol Basic units Length Metre m Mass Kilogram kg Time Second s Electric current Ampere A Thermodynamic temperature Kelvin K Amount of substance Mole mol Luminous intensity Candela cd Additional units Plane angle Radian rad Solid angle Steradian sr Derived units Energy Joule J m2 kg s−2 ≡ Nm Force Newton N mkgs−2 ≡ Jm−1 Pressure Pascal Pa m−1 kg s−2 ≡ Nm−2 Electrical charge Coulomb C s A Magnetic flux Weber Wb m2 kg s−2 A−1 Magnetic flux density Tesla T kg s−2 A−1 ≡ Vsm−2 Magnetic field strength A m−1 Inductance Henry H m2 kg s−2 A−2 Power Watt W m2 kg s−2 ≡ Js−1 Electric potential difference Volt V m2 kg s−3 A ≡ JC−1 Frequency Hertz Hz s−1 M. Gargaud et al. (Ed.): Lectures in Atrobiology, Vol. I, pp. 697–792 c Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2005 698 2 Useful Astrobiological Data 2. Other Units Name Symbol Length Fermi fm 10−15 m Angstrom A1˚ 0−10 m Micron µm10−6 m Time Minute min, mn 60s Hour h 3600 s Day d 86 400s Year a, y 3.156 × 107 s Volume Litre l 10−3 m3 ≡ 1dm3 Mass Ton t 103 kg Temperature Degree Celsius ◦C Temperature comparison: 0 ◦C = 273.15 K = 32 ◦F 100 ◦C = 373.15 K = 212 ◦F Temperature scale: K=◦C=1.8 ◦F Force Dyne (cgs system) dyn 10−5 N Energy Erg (cgs system) erg 10−7 J Calorie cal 4.184 J Electron-volt eV 1.6 × 10−19 J Kilowatt-hour 3600 × 103 J= 8.6042 × 105 cal Pressure Bar bar 105 Pa Atmosphere atm 1.01325 × 105 Pa mercury mm torr 1.3332 × 102 Pa Magnetic Gauss gauss 10−4 T flux density Concentration Molarity M mol l−1 Molar mass g/mol Angle Degree ◦ 1◦ = π/180 =1.74 × 10−2 rad Minute 1 = π/10 800 =2.91 × 10−4 rad Second 1 = π/648 000 =4.85 × 10−6 rad 1Radian = 57.296 ◦ =3.44 × 103 =2.06 × 105 2.1 Physical and Chemical Data 699 3. -

Chapter 15 Navigational Astronomy

CHAPTER 15 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS 1500. Definitions plain their physical properties. Navigational astronomy deals with their coordinates, time, and motions. The sym- The science of Astronomy studies the positions and bols commonly recognized in navigational astronomy are motions of celestial bodies and seeks to understand and ex- given in Table 1500. Table 1500. Astronomical symbols. 217 218 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY 1501. The Celestial Sphere absolute motion. Since all motion is relative, the position of the observer must be noted when discussing planetary Looking at the sky on a dark night, imagine that ce- motion. From the Earth we see apparent motions of lestial bodies are located on the inner surface of a vast, celestial bodies on the celestial sphere. In considering how Earth-centered sphere (Figure 1501). This model is use- planets follow their orbits around the Sun, we assume a ful since we are only interested in the relative positions hypothetical observer at some distant point in space. When and motions of celestial bodies on this imaginary sur- discussing the rising or setting of a body on a local horizon, face. Understanding the concept of the celestial sphere is we must locate the observer at a particular point on the most important when discussing sight reduction in Chapter 20. Earth because the setting Sun for one observer may be the rising Sun for another. 1502. Relative and Apparent Motion Motion on the celestial sphere results from the motions in space of both the celestial body and the Earth. Without Celestial bodies are in constant motion. There is no special instruments, motions toward and away from the fixed position in space from which one can observe Earth cannot be discerned. -

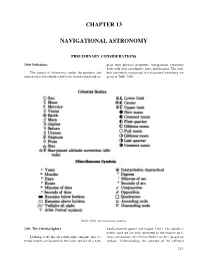

Chapter 13 Navigational Astronomy

CHAPTER 13 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS 1300. Definitions plain their physical properties. Navigational astronomy deals with their coordinates, time, and motions. The sym- The science of Astronomy studies the positions and bols commonly recognized in navigational astronomy are motions of celestial bodies and seeks to understand and ex- given in Table 1300. Table 1300. Astronomical symbols. 1301. The Celestial Sphere useful since we are only interested in the relative posi- tions and motions of celestial bodies on this imaginary Looking at the sky on a dark night, imagine that ce- surface. Understanding the concept of the celestial lestial bodies are located on the inner surface of a vast, sphere is most important when discussing sight reduc- Earth-centered sphere (see Figure 1301). This model is tion in Chapter 19. 215 216 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY Figure 1301. The celestial sphere. 1302. Relative and Apparent Motion 1303. Astronomical Distances Celestial bodies are in constant motion. There is no We can consider the celestial sphere as having an in- fixed position in space from which one can observe finite radius because distances between celestial bodies are absolute motion. Since all motion is relative, the position of so vast. For an example in scale, if the Earth were represent- the observer must be noted when discussing planetary ed by a ball one inch in diameter, the Moon would be a ball motion. From the Earth we see apparent motions of celestial one-fourth inch in diameter at a distance of 30 inches, the bodies on the celestial sphere. In considering how planets Sun would be a ball nine feet in diameter at a distance of follow their orbits around the Sun, we assume a nearly a fifth of a mile, and Pluto would be a ball half hypothetical observer at some distant point in space. -

Chapter 13 Navigational Astronomy

CHAPTER 13 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS 1300. Definitions plain their physical properties. Navigational astronomy deals with their coordinates, time, and motions. The sym- The science of Astronomy studies the positions and bols commonly recognized in navigational astronomy are motions of celestial bodies and seeks to understand and ex- given in Table 1300. Table 1300. Astronomical symbols. 1301. The Celestial Sphere Earth-centered sphere (see Figure 1301). This model is useful since we are only interested in the relative posi- Looking at the sky on a dark night, imagine that ce- tions and motions of celestial bodies on this imaginary lestial bodies are located on the inner surface of a vast, surface. Understanding the concept of the celestial 215 216 NAVIGATIONAL ASTRONOMY sphere is most important when discussing sight reduc- tion in Chapter 19. Figure 1301. The celestial sphere. 1302. Relative and Apparent Motion 1303. Astronomical Distances Celestial bodies are in constant motion. There is no We can consider the celestial sphere as having an in- fixed position in space from which one can observe finite radius because distances between celestial bodies are absolute motion. Since all motion is relative, the position of so vast. For an example in scale, if the Earth were represent- the observer must be noted when discussing planetary ed by a ball one inch in diameter, the Moon would be a ball motion. From the Earth we see apparent motions of celestial one-fourth inch in diameter at a distance of 30 inches, the Sun would be a ball nine feet in diameter at a distance of bodies on the celestial sphere. -

Elizabeth Chesley Baity; Anthony F

Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy So Far [and Comments and Reply] Elizabeth Chesley Baity; Anthony F. Aveni; Rainer Berger; David A. Bretternitz; Geoffrey A. Clark; James W. Dow; P. -R. Giot; David H. Kelley; Leo S. Klejn; H. H. E. Loops; Rolf Muller; Richard Pittioni; Emilie Pleslova-Stikova; Zenon S. Pohorecky; Jonathan E. Reyman; S. B. Roy; Charles H. Smiley; Dean R. Snow; James L. Swauger; P. M. Vermeersch Current Anthropology, Vol. 14, No. 4. (Oct., 1973), pp. 389-449. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0011-3204%28197310%2914%3A4%3C389%3AAAESF%5B%3E2.0.CO%3B2-R Current Anthropology is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world.