James Mooney, Among the Cherokee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Vegetation of the Nattai and Bargo Reserves

The Native Vegetation of the Nattai and Bargo Reserves Project funded under the Central Directorate Parks and Wildlife Division Biodiversity Data Priorities Program Conservation Assessment and Data Unit Conservation Programs and Planning Branch, Metropolitan Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CADU (Central) Manager Special thanks to: Julie Ravallion Nattai NP Area staff for providing general assistance as well as their knowledge of the CADU (Central) Bioregional Data Group area, especially: Raf Pedroza and Adrian Coordinator Johnstone. Daniel Connolly Citation CADU (Central) Flora Project Officer DEC (2004) The Native Vegetation of the Nattai Nathan Kearnes and Bargo Reserves. Unpublished Report. Department of Environment and Conservation, CADU (Central) GIS, Data Management and Hurstville. Database Coordinator This report was funded by the Central Peter Ewin Directorate Parks and Wildlife Division, Biodiversity Survey Priorities Program. Logistics and Survey Planning All photographs are held by DEC. To obtain a Nathan Kearnes copy please contact the Bioregional Data Group Coordinator, DEC Hurstville Field Surveyors David Thomas Cover Photos Teresa James Nathan Kearnes Feature Photo (Daniel Connolly) Daniel Connolly White-striped Freetail-bat (Michael Todd), Rock Peter Ewin Plate-Heath Mallee (DEC) Black Crevice-skink (David O’Connor) Aerial Photo Interpretation Tall Moist Blue Gum Forest (DEC) Ian Roberts (Nattai and Bargo, this report; Rainforest (DEC) Woronora, 2003; Western Sydney, 1999) Short-beaked Echidna (D. O’Connor) Bob Wilson (Warragamba, 2003) Grey Gum (Daniel Connolly) Pintech (Pty Ltd) Red-crowned Toadlet (Dave Hunter) Data Analysis ISBN 07313 6851 7 Nathan Kearnes Daniel Connolly Report Writing and Map Production Nathan Kearnes Daniel Connolly EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report describes the distribution and composition of the native vegetation within and immediately surrounding Nattai National Park, Nattai State Conservation Area and Bargo State Conservation Area. -

Conservation Fisheries, Inc. and the Reintroduction of Our Native Species

Summer (Aug.) 2011 American Currents 18 Conservation Fisheries, Inc. and the Reintroduction of Our Native Species J.R. Shute1 and Pat Rakes1 with edits by Casper Cox2 1 - Conservation Fisheries, Inc., 3424 Division St., Knoxville, TN 37919, (865)-521-6665 2 - 1200 B. Dodds Ave., Chattanooga, TN 37404, [email protected] n the southeastern U.S. there have been only a few fish In 1957, a “reclamation” project was conducted in Abrams reintroductions attempted. The reintroduction of a spe- Creek. In conjunction with the closing of Chilhowee Dam on the cies where it formerly occurred, but is presently extir- Little Tennessee River, all fish between Abrams Falls and the mouth pated,I is a technique used to recover a federally listed species. of the creek (19.4 km/12 miles to Chilhowee Reservoir) were elimi- This technique is often suggested as a specific task by the U.S. nated. This was done using a powerful ichthyocide (Rotenone) in an Fish & Wildlife Service when they prepare recovery plans for attempt to create a “trophy” trout fishery in the park. Since then, many endangered species. Four fishes, which formerly occurred in of the 63 fishes historically reported from Abrams Creek have made Abrams Creek, located in the Great Smoky Mountains National their way back, however nearly half have been permanently extirpated Park, are now on the federal Endangered Species List. These because of the impassable habitat that separates Abrams Creek from are: the Smoky Madtom; Yellowfin Madtom; Citico Darter; other stream communities, including the aforementioned species. and the Spotfin Chub. The recovery plans for all of these fishes These stream fishes are not able to survive in or make their way recommend reintroduction into areas historically occupied by through the reservoir that Chilhowee Dam created to repopulate flow- the species. -

Dubbo Zirconia Project

Dubbo Zirconia Project Aquatic Ecology Assessment Prepared by Alison Hunt & Associates September 2013 Specialist Consultant Studies Compendium Volume 2, Part 7 This page has intentionally been left blank Aquatic Ecology Assessment Prepared for: R.W. Corkery & Co. Pty Limited 62 Hill Street ORANGE NSW 2800 Tel: (02) 6362 5411 Fax: (02) 6361 3622 Email: [email protected] On behalf of: Australian Zirconia Ltd 65 Burswood Road BURSWOOD WA 6100 Tel: (08) 9227 5677 Fax: (08) 9227 8178 Email: [email protected] Prepared by: Alison Hunt & Associates 8 Duncan Street ARNCLIFFE NSW 2205 Tel: (02) 9599 0402 Email: [email protected] September 2013 Alison Hunt & Associates SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Part 7: Aquatic Ecology Assessment Dubbo Zirconia Project Report No. 545/05 This Copyright is included for the protection of this document COPYRIGHT © Alison Hunt & Associates, 2013 and © Australian Zirconia Ltd, 2013 All intellectual property and copyright reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part of this report may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system or adapted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to Alison Hunt & Associates. Alison Hunt & Associates RW CORKERY & CO. PTY. LIMITED AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Dubbo Zirconia Project Aquatic Ecology Final September 2013 SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Part 7: Aquatic Ecology Assessment Dubbo Zirconia Project Report No. 545/05 SUMMARY Alison Hunt & Associates Pty Ltd was commissioned by RW Corkery & Co Pty Limited, on behalf of Australian Zirconia Limited (AZL), to undertake an assessment of aquatic ecology for the proposed development of the Dubbo Zirconia Project (DZP), which would be located at Toongi, approximately 25 km south of Dubbo in Central West NSW. -

Articulating Culturally Sensitive Knowledge Online: a Cherokee Case Study*

Articulating Culturally Sensitive Knowledge Online: A * Cherokee Case Study Robert Leopold Abstract: This article examines the online management of culturally sensitive knowledge through a discussion of a collaboration between the Museum of the Cherokee Indian and the Smithsonian Institution. It discusses the roles of the two institutions in a digital repatriation project involving an extensive body of 19th and 20th century manuscripts as well as the assumptions that informed their respective decisions regarding the online presentation of traditional cultural expressions. The case study explores some challenges involved in providing online access to culturally sensitive materials: first, by probing disparate senses of the term community, and then through a close examination of a particular class of heritage materials about which many Cherokee feel deeply ambivalent and for which notions of collective ownership are especially problematic. The Cherokee knowledge repatriation project offers a novel model for the circulation of digital heritage materials that may have wider applicability. The success of the project suggests that collaboration between tribal and non-tribal institutions may lead to more creative solutions for managing traditional cultural expressions than either alone can provide. [Keywords: Access Restrictions, Digital Repatriation, Culturally Sensitive Materials, Ethnographic Archiving, Knowledge Management. Keywords in italics are derived from the American Folklore Society Ethnographic Thesaurus, a standard nomenclature for the ethnographic disciplines.] Not long ago, I was giving a behind-the-scenes tour of the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Archives when a member of the group asked me how our archives deals with culturally sensitive collections. Coincidentally, we were standing in front of a recent acquisition: the papers of Frederica de Laguna (1906-2004), an eminent anthropologist who conducted research among the Tlingit people of the Pacific Northwest Coast between 1949 and 1954. -

Mid Coxs River Subcatchment

Mid Coxs River Mid Coxs Appendix 4.2 Appendix Subcatchment summaries Subcatchment Mid Coxs River Subcatchment River Mid Coxs The Mid Coxs River subcatchment is located in the far-west section of the Hawkesbury Nepean catchment. It is characterised by narrow granite valleys and contains the World Heritage listed Jenolan Caves Karst Conservation Reserve. The subcatchment has signifi cant areas in reserved land in its lower reaches in the Kanagra Boyd National Park, part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. The subcatchment is highly valued for its recreational values by local and regional communities. Flows in the Mid Coxs River are impacted by impoundment at Lake Lyell. In the upper area of the subcatchment, there is signifi cant rural development, and pine plantations in the tributary headwaters both of which have altered the vegetation of this subcatchment. The impacts of these activities need to be well managed to prevent degradation of the near intact reaches downstream. There is a major Landcare association, the Lithgow Oberon Landcare Association, and numerous Landcare groups working in the subcatchment, as well as weed control and mapping programs undertaken by the National Parks and Wildlife Service. HAWKESBURY NEPEAN RIVER HEALTH STRATEGY 53 54 54 Reach Management Recommendations – Mid Coxs River Subcatchment Reach Name Reach Riparian Land Reach Values Reach Threats Reach management recommendations Description Management (Planning, Education, Works, Monitoring, Institutional) Category Megalong Conservation • Develop -

Threatened and Ednagered Species of Tennessee

River Ecosystems What are River Ecosystems? Tennessee not only has the greatest Rare and Unique Plants and Animals Rivers are more than just the water diversity of freshwater fish species in Generally disregarded and unknown, flowing between their banks. The the country, but it also supports an non-game freshwater aquatic species health of the land surrounding rivers abundance of crayfish, mollusks, and are part of the web of life that directly affects the water quality and some aquatic insects. There are over supports the game species we enjoy the life that exists in and around 300 fish species in Tennessee, fishing for and eating and the wildlife them. Tennessee's rivers are home to 71 crayfish, 129freshwater mussels, we enjoy watching. Non-game fish a rich and diverse natural heritage and 96 freshwater snails. In fact, the species represent an important food and support a wealth of cultural Ohio River basin, which encompasses source for fishes, birds, and history, with important archaeological most of Tennessee, contains the mammals. Freshwater mussels are and historical sites. There are more world's richest diversity of freshwater filter feeders, acting like miniature than 15,000miles of tremendously mussels. The Nature Conservancy, in water purifiers. They capture and diverse rivers that flow across their report entitled Rivers of Life, remove large quantities of tiny algae the state. found that the center for aquatic and plankton that most other aquatic biodiversity is largely concentrated in animals cannot eat. They, in turn, Why are River Ecosystems the Tennessee, Cumberland, Ohio, become food for river otters, Important? and Mobile River basins, ofwhich muskrats, fishes, and other wildlife An extraordinary variety of aquatic sizeable portions of each flow through species. -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No

994 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 44 Chambers, Ian McKenzie, I 9 Killarney Street, Takapuna, Hutchinson, Howard Desmond, 999 Dominion Road, Mount Auckland. Roskill , Auckland. Cherrie, William Robert, 10 Cremorne Avenue, Palmerston Hyde, James Henry Nowell, 45 Milton Terrace, Picton. North. Ibbotson, Norman Harvey, 6 Hardley Street, Hamilton. Cherry, Mrs Ada, 103 Eden Street, Island Bay, Wellington. Innes, James Ian, Haldon Station, Fairlie, Clarke; Hector James, "Te Wairoa", Clarke Road, Te Puna, Iremonger, Harold Arthur, Ocean Road, Whangamata. R.D. 2, Tauranga. Irving, Hugh Douglas, 68 High Street, Rosedale, Invercargill. Clemens, Clarence Herbert, 83 St. Andrews Square, Christ Jack, Mrs Winifred, 9 Hillside Crescent, Mount Eden, church. Auckland. Cloake, Arthur Lewis, 89 Liardet Street, Vogeltown, Welling- Jackson, Albert Ernest, Wallacetown, Southland. ton. Jamieson, Robert Guthrie, I Linda Street, Oakura, Taranaki. Colvin, Henry Abiel, 112 McFarlane Street, Hamilton East. Jennings, George Grey, Otara, No. 5 R.D., Invercargill. Corbet, Gordon Morell, 123 Tweed Street, Invercargill. Joseph, David Peter, 20 Landscape Road, Mount Eden, Cox, Norman Douglas, 35 Cranford Street, St. Albans, Auckland. Christchurch. Judd, Alfred Gwilliam, 26 James Street, Whakatane. Cox, Robert Donald, 12 Ventnor Road, Remuera, Auckland. Kay, Mrs Grace Edith Meliora, "Orakau", Te Awamutu. Crooombe, Alfred Cyril, 111 Calliope Road, Devonport, Kelliher, Patrick, 5 Sydney Street, Palmerston North. Auckland. Kelly, George Alexander Kirk, 153 Main South. Road, Sock Culver, Edwin Harold, 905 Heathcoate Avenue, Hastings. burn. Currie, Clement Stanley, 44 Brice .Street, Taupo. Kennedy, Maurice Whitfield, 166 Rossall Street, Merivale, Dalziel, James McAteer, 20 Jackson Street, Dunedin. Christchurch. Dean, Alan John, Otira, Westland. King, William Ge·orge, Ladbrooks, No. -

PROGRAM April– May – June 2021

PROGRAM April– May – June 2021 Lilo Heathcote NP Feb 2021 PO BOX 250 SUTHERLAND NSW 1499 ABN 28 780 135 294 http://www.sutherlandbushwalkers.org.au INTRODUCTION Sutherland Bushwalkers Club provides opportunities for safe bush sports activities. Membership is open to all 18 years of age and over and currently stands at approx. 300 members. The club meets on the last Wednesday of each month (except Jan and Dec) at the Sutherland Council Stapleton Avenue Community Centre, cnr. Stapleton Ave & Belmont St, Sutherland at 7.00 pm. For membership enquiries and/or further information, see the club’s website or email us at [email protected] BOOKINGS It is imperative that bookings are made directly with the Activity Organiser. At least 4 days’ notice for one-day activities and 10 days for o/night activities should be given if you wish to participate. Frequently there is a limit on the number of people, so it is best to book early. Visitors are welcome on activities if the Activity Organiser agrees. MEETING AND DEPARTURE TIMES The time and conditions for meeting and departing cannot be extended to wait for those who are late. If you find that you are not able to attend, please advise the Activity Organiser immediately. This may allow another person to attend when numbers are limited. TRANSPORT Car pooling is an option and the costs are shared between the passengers. The following formula is suggested: calculate contribution of each person by doubling the cost of fuel and dividing by the number of occupants, including the driver, and share equally any additional costs, eg entrance fees, road tolls etc. -

Trail-Map-GSMNP-06-2014.Pdf

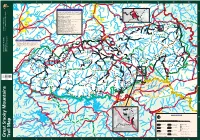

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 T E To Knoxville To Knoxville To Newport To Newport N N E SEVIERVILLE S 321 S E E 40 411 R 32 I V 441 E R r T 411 r Stream Crossings re e CHEROKEE NATIONAL FOREST r y Exit L T m a itt ) A le in m w r 443 a a k e Nearly all park trails cross small streams—making very wet crossings t 1.0 C t P r n n i i t a 129 g u w n P during flooding. The following trails that cross streams with no bridges e o 0.3 n i o M u r s d n ve e o se can be difficult and dangerous at flood stage. (Asterisks ** indicate the Ri ab o G M cl 0.4 r ( McGhee-Tyson L most difficult and potentially dangerous.) This list is not all-inclusive. e s ittl 441 ll Airport e w i n o Cosby h o 0.3 L ot e Beard Cane Trail near campsite #3 Fo Pig R R ive iv r Beech Gap Trail on Straight Fork Road er Cold Spring Gap Trail at Hazel Creek 0.2 W Eagle Creek Trail** 15 crossings e 0.3 0.4 SNOWBIRD s e Tr t Ridg L Fork Ridge Trail crossing of Deep Creek at junction with Deep Creek Trail en 0.4 o P 416 D w IN r e o k Forney Creek Trail** seven crossings G TENNESSEE TA n a nWEB a N g B p Gunter Fork Trail** five crossingsU S OUNTAIN 0.1 Exit 451 O M 32 Hannah Mountain Trail** justM before Abrams Falls Trail L i NORTH CAROLINA tt Jonas Creek Trail near Forney Creek le Little River Trail near campsite #30 PIGEON FORGE C 7.4 Long Hungry Ridge Trail both sides of campsite #92 Pig o 35 Davenport eo s MOUNTAIN n b mere MARYVILLE Lost Cove Trail near Lakeshore Trail junction y Cam r Trail Gap nt Waterville R Pittman u C 1.9 Meigs Creek Trail 18 crossings k i o h E v Big Creek E e M 1.0 e B W e Mt HO e Center 73 Mount s L Noland Creek Trail** both sides of campsite #62 r r 321 Hen Wallow Falls t 2.1 HI C r Cammerer n C Cammerer C r e u 321 1.2 e Panther Creek Trail at Middle Prong Trail junction 0.6 t e w Trail Br Tr k o L Pole Road Creek Trail near Deep Creek Trail M 6.6 2.3 321 a 34 321 il Rabbit Creek Trail at the Abrams Falls Trailhead d G ra Gatlinburg Welcome Center 5.8 d ab T National Park ServiceNational Park U.S. -

COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, MACARTHUR, THROSBY And

BELLS LIN E OF RD RD Riv g C K Y IL k RD ay 1 L Howes Cape Three Points Creek L R Bellbird Hill Hawkesbury D RD R Pie Dish Hill Y Y Cogra Hill DEMONDR Campbells O RR R FE Ettalong RD Mourawaring Point RLY E Bar P L MANS oint M WISE D G D O R R R C E Umina SCENIC E N L A R L T F I THE Belubula Chifley Dam E O V - T K R C D RD S A E E Coxs IN S Bombi Point Y W L E Carcoar N Y RD A A Lake Y G L ON B BELLS W T H PA N I Hawkesbury River A Grose D M R Fish I Grose TA S T A NORTHERN E C River E V K River U C A R R River C R AJ O O F Broken Bay NG R River E River RD B L I D HORNSBY WESTERN W D L W R O IND Y SOR FW RIC BLACKTOW HMON N D W River RD O IC River T IF C JENOLAN A P ITT E N RD T P L S RD T BAY S D A 2 C R D IE Campbells R R W Pittwater A E U N Q Lake C D A R M Rowlands River D R Y E PITTWATER W N BLACKTOWN -IN BAULKHAM HILLS D River D Y S 9 O G S R ALS ESBURY TO Y HAWK N E RD JO H N H D E G R LITHGOW W R A R Y E 2 R R BA E I D L C R W R R T H COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, D E I S M C MACQUARIERiver S T H 1 E A O R N M N C D MACKELLAR Lake Oberon O RD N VA S L T D E E A N D 3 V E A M R ON R E A A E G H C MITCHELL H H MACKELLAR W T 10 Y Nepean R R Duckmaloi O L N MACARTHUR, THROSBY and WERRIWA Y MITCHELL R L STERN Y W WE IN MAIN D RD N I D F S 3 F B R O O O R B R R O E Little River E B S W S T E T STLIN GREENWAYK PKW RD M7 CA VALE Y ST Fish LE 7 THE Y A H W N I H O Campbells LL M W CALARE Kedumba RD P W Little BLACKTOWN A NORTH River R WARRINGAH Y BRADFIELDKU-RING-GAI Y C BLUE D I F CHIFLEY I Lane C MAIN BRADFIELD JENOLAN LINDSAY CALARE CHIFLEYRLY -

Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation Partnership 2016 Accomplishment Report

Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation Partnership 2016 Accomplishment Report 2016 saw the Little Tennessee Native Fish Conservation What is the Little Tennessee Native Partnership continue existing and begin new projects Fish Conservation Partnership? that give people living across the basin more opportu- A group of local, state, and national organ- nities to learn about, and hopefully enjoy, the Little izations that recognize the significance of the river basin’s streams and are working Tennessee River and its tributary streams. with local communities to conserve stream life and develop stream-based economic Expansion of river snorkeling opportunities opportunity. River snorkeling has long been offered in Tennessee as a way to share the incredible aquatic diversity of these rivers with anyone willing to About Little Tennessee River Basin don a wetsuit and hit the water. The partnership expanded those The Little Tennessee River Basin stretches offerings into North Carolina. A grant from the North Carolina Chapter from northeast Georgia, across North Car- of the American Fisheries Society was matched with funds from the olina, into east Tennessee and includes the North Carolina Wildlife Federation, allowing the partnership to pur- Little Tennessee River itself, as well as the chase snorkels, wetsuits, and other materials partnership members Tuckasegee, Nantahala, Cheoah, Oco- can use to offer snorkeling programs across the Little Tennessee River naluftee, and Tellico rivers, and myriad basin. Mainspring Conservation Trust and the Eastern -

Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Great Smoky Mountains National Park

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Service National Park Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Great Smoky Mountains NATIONAL PARK Historic Resource Study Resource Historic Park National Mountains Smoky Great Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 April 2016 VOL Historic Resource Study | Volume 1 1 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration. GRSM 133/134404/A April 2016 GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 FRONT MATTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................