Strategic Plan 2012‐2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Federal Register/Vol. 66, No. 27/Thursday, February 8, 2001/Proposed Rules

9540 Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 27 / Thursday, February 8, 2001 / Proposed Rules impose a minimal burden on small regulatory effect of the critical habitat white to bluish-white, changing to a entities. designation does not extend beyond salmon, pinkish, or brownish color in those activities funded, permitted, or the central and beak cavity portions of E. Federal Rules That May Duplicate, carried out by Federal agencies. State or the shell; some specimens may be Overlap, or Conflict With the Proposed private actions, with no Federal marked with irregular brownish Rules involvement, are not affected. blotches (adapted from Clarke 1981). 37. None. Section 4 of the Act requires us to Clarke (1981) contains a detailed consider the economic and other description of the species’ shell, with Ordering Clauses relevant impacts of specifying any illustrations; Ortmann (1921) discussed 38. Pursuant to Sections 1, 3, 4, 201– particular area as critical habitat. We soft parts. 205, 251 of the Communications Act of solicit data and comments from the Distribution, Habitat, and Life History 1934, as amended, 47 U.S.C. 151, 153, public on all aspects of this proposal, 154, 201–205, and 251, this Second including data on the economic and The Appalachian elktoe is known Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking other impacts of the designation. We only from the mountain streams of is hereby Adopted. may revise this proposal to incorporate western North Carolina and eastern 39. The Commission’s Consumer or address comments and other Tennessee. Although the complete Information Bureau, Reference information received during the historical range of the Appalachian Information Center, Shall Send a copy comment period. -

Conservation Fisheries, Inc. and the Reintroduction of Our Native Species

Summer (Aug.) 2011 American Currents 18 Conservation Fisheries, Inc. and the Reintroduction of Our Native Species J.R. Shute1 and Pat Rakes1 with edits by Casper Cox2 1 - Conservation Fisheries, Inc., 3424 Division St., Knoxville, TN 37919, (865)-521-6665 2 - 1200 B. Dodds Ave., Chattanooga, TN 37404, [email protected] n the southeastern U.S. there have been only a few fish In 1957, a “reclamation” project was conducted in Abrams reintroductions attempted. The reintroduction of a spe- Creek. In conjunction with the closing of Chilhowee Dam on the cies where it formerly occurred, but is presently extir- Little Tennessee River, all fish between Abrams Falls and the mouth pated,I is a technique used to recover a federally listed species. of the creek (19.4 km/12 miles to Chilhowee Reservoir) were elimi- This technique is often suggested as a specific task by the U.S. nated. This was done using a powerful ichthyocide (Rotenone) in an Fish & Wildlife Service when they prepare recovery plans for attempt to create a “trophy” trout fishery in the park. Since then, many endangered species. Four fishes, which formerly occurred in of the 63 fishes historically reported from Abrams Creek have made Abrams Creek, located in the Great Smoky Mountains National their way back, however nearly half have been permanently extirpated Park, are now on the federal Endangered Species List. These because of the impassable habitat that separates Abrams Creek from are: the Smoky Madtom; Yellowfin Madtom; Citico Darter; other stream communities, including the aforementioned species. and the Spotfin Chub. The recovery plans for all of these fishes These stream fishes are not able to survive in or make their way recommend reintroduction into areas historically occupied by through the reservoir that Chilhowee Dam created to repopulate flow- the species. -

Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology an Interactive Guide Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology PK Gupta

PK Gupta Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology An Interactive Guide Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology PK Gupta Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology An Interactive Guide PK Gupta Toxicology Consulting Group Academy of Sciences for Animal Welfare Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India ISBN 978-3-030-22249-9 ISBN 978-3-030-22250-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22250-5 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland Preface The book entitled Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology: An Interactive Guide covers a broad spectrum of topics for the students specializing in veterinary toxicology and veterinary medical practitioners. -

Record of Decision (ROD)

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY EPA REGION 1 – NEW ENGLAND RECORD OF DECISION NYANZA CHEMICAL WASTE DUMP SUPERFUND SITE OPERABLE UNIT 02 ASHLAND, MASSACHUSETTS JULY 2020 PART 1: THE DECLARATION FOR THE RECORD OF DECISION A. SITE NAME AND LOCATION B. STATEMENT OF BASIS AND PURPOSE C. ASSESSMENT OF SITE D. DESCRIPTION OF SELECTED REMEDY E. STATUTORY DETERMINATIONS F. SPECIAL FINDINGS G. DATA CERTIFICATION CHECKLIST H. AUTHORIZING SIGNATURES PART 2: THE DECISION SUMMARY A. SITE NAME, LOCATION, AND BRIEF DESCRIPTION B. SITE HISTORY AND ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITIES 1. History of Site Activities 2. History of Federal and State Investigations and Removal and Remedial Actions 3. History of CERCLA Enforcement Activities C. COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION D. SCOPE AND ROLE OF OPERABLE UNIT OR RESPONSE ACTION E. SITE CHARACTERISTICS F. CURRENT AND POTENTIAL FUTURE SITE AND RESOURCE USES G. SUMMARY OF SITE RISKS 1. Human Health Risk Assessment 2. Supplemental Human Health Risk Assessment 3. Supplemental Evaluation Following Risk Assessment 4. Ecological Risk Assessment 5. Basis for Remedial Action H. REMEDIAL ACTION OBJECTIVES I. DEVELOPMENT AND SCREENING OF ALTERNATIVES J. DESCRIPTION OF ALTERNATIVES K. SUMMARY OF COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES L. THE SELECTED REMEDY M. STATUTORY DETERMINATIONS N. DOCUMENTATION OF NO SIGNIFICANT CHANGES O. STATE ROLE Record of Decision Nyanza Chemical Waste Dump Superfund Site: OU2 July 2020 Ashland, Massachusetts Page 2 of 73 PART 3: THE RESPONSIVENESS SUMMARY APPENDICES Appendix A: MassDEP Letter of Concurrence Appendix B: Tables Appendix C: Figures Appendix D: ARARs Tables Appendix E: References Appendix F: Acronyms and Abbreviations Appendix G: Administrative Record Index and Guidance Documents Record of Decision Nyanza Chemical Waste Dump Superfund Site: OU2 July 2020 Ashland, Massachusetts Page 3 of 73 PART 1: THE DECLARATION FOR THE RECORD OF DECISION A. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LIST OF THE RARE PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 2012 Edition Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist and John Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents LIST FORMAT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 NORTH CAROLINA RARE PLANT LIST ......................................................................................................................... 10 NORTH CAROLINA PLANT WATCH LIST ..................................................................................................................... 71 Watch Category -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae)

1 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio and surrounding watersheds by Robert A. Krebs Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences Cleveland State University Cleveland, Ohio, USA 44115 September 2015 (Revised from 2009) 2 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio, and surrounding watersheds Acknowledgements I thank Dr. David Klarer for providing the stimulus for this project and Kristin Arend for a thorough review of the present revision. The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve provided housing and some equipment for local surveys while research support was provided by a Research Experiences for Undergraduates award from NSF (DBI 0243878) to B. Michael Walton, by an NOAA fellowship (NA07NOS4200018), and by an EFFRD award from Cleveland State University. Numerous students were instrumental in different aspects of the surveys: Mark Lyons, Trevor Prescott, Erin Steiner, Cal Borden, Louie Rundo, and John Hook. Specimens were collected under Ohio Scientific Collecting Permits 194 (2006), 141 (2007), and 11-101 (2008). The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), established by section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information on these preserves and programs is available from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office for Coastal Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U. S. Department of Commerce, 1305 East West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. -

Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan (Leptodea leptodon) February 2010 Department of the Interior United States Fish and Wildlife Service Great Lakes – Big Rivers Region (Region 3) Fort Snelling, MN Cover photo: Female scaleshell mussel (Leptodea leptodon), taken by Dr. M.C. Barnhart, Missouri State University Disclaimer This is the final scaleshell mussel (Leptodea leptodon) recovery plan. Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions believed required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after being signed by the Regional Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modifications as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. The plan will be revised as necessary, when more information on the species, its life history ecology, and management requirements are obtained. Literature citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Scaleshell Mussel Recovery Plan (Leptodea leptodon). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota. 118 pp. Recovery plans can be downloaded from the FWS website: http://endangered.fws.gov i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many individuals and organizations have contributed to our knowledge of the scaleshell mussel and work cooperatively to recover the species. -

Threatened and Ednagered Species of Tennessee

River Ecosystems What are River Ecosystems? Tennessee not only has the greatest Rare and Unique Plants and Animals Rivers are more than just the water diversity of freshwater fish species in Generally disregarded and unknown, flowing between their banks. The the country, but it also supports an non-game freshwater aquatic species health of the land surrounding rivers abundance of crayfish, mollusks, and are part of the web of life that directly affects the water quality and some aquatic insects. There are over supports the game species we enjoy the life that exists in and around 300 fish species in Tennessee, fishing for and eating and the wildlife them. Tennessee's rivers are home to 71 crayfish, 129freshwater mussels, we enjoy watching. Non-game fish a rich and diverse natural heritage and 96 freshwater snails. In fact, the species represent an important food and support a wealth of cultural Ohio River basin, which encompasses source for fishes, birds, and history, with important archaeological most of Tennessee, contains the mammals. Freshwater mussels are and historical sites. There are more world's richest diversity of freshwater filter feeders, acting like miniature than 15,000miles of tremendously mussels. The Nature Conservancy, in water purifiers. They capture and diverse rivers that flow across their report entitled Rivers of Life, remove large quantities of tiny algae the state. found that the center for aquatic and plankton that most other aquatic biodiversity is largely concentrated in animals cannot eat. They, in turn, Why are River Ecosystems the Tennessee, Cumberland, Ohio, become food for river otters, Important? and Mobile River basins, ofwhich muskrats, fishes, and other wildlife An extraordinary variety of aquatic sizeable portions of each flow through species. -

Comparison of Selected in Vitro Assays for Assessing the Toxicity of Chemicals and Their Mixtures

COMPARISON OF SELECTED IN VITRO ASSAYS FOR ASSESSING THE TOXICITY OF CHEMICALS AND THEIR MIXTURES Rola Azzi A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chemical Safety and Applied Toxicology Laboratories School of Safety Science Faculty of Science The University of New South Wales June 2006 Certificate of Originality Certificate of Originality I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any degree at UNSW or any other education institution, except where due acknowledgment is made in the thesis. Any contributions made to the research by others, which whom I have worked, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Rola Azzi June 2006 i Acknowledgments Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor Dr Amanda Hayes for her assistance, constant encouragement and expertise. Without her support and guidance this project would not have been possible. I am also grateful to Associate Professor Chris Winder, for his constant support, advice, and scientific expertise throughout my work on this project. I would also like to express my sincerest gratitude and appreciation to my uncle, Associate Professor Rachad Saliba, who was a constant support during the writing of this thesis, and was devoted to helping me grasp the science of statistics, and its ability to transform numbers into a story. -

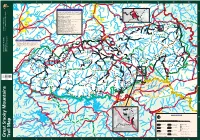

Trail-Map-GSMNP-06-2014.Pdf

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 T E To Knoxville To Knoxville To Newport To Newport N N E SEVIERVILLE S 321 S E E 40 411 R 32 I V 441 E R r T 411 r Stream Crossings re e CHEROKEE NATIONAL FOREST r y Exit L T m a itt ) A le in m w r 443 a a k e Nearly all park trails cross small streams—making very wet crossings t 1.0 C t P r n n i i t a 129 g u w n P during flooding. The following trails that cross streams with no bridges e o 0.3 n i o M u r s d n ve e o se can be difficult and dangerous at flood stage. (Asterisks ** indicate the Ri ab o G M cl 0.4 r ( McGhee-Tyson L most difficult and potentially dangerous.) This list is not all-inclusive. e s ittl 441 ll Airport e w i n o Cosby h o 0.3 L ot e Beard Cane Trail near campsite #3 Fo Pig R R ive iv r Beech Gap Trail on Straight Fork Road er Cold Spring Gap Trail at Hazel Creek 0.2 W Eagle Creek Trail** 15 crossings e 0.3 0.4 SNOWBIRD s e Tr t Ridg L Fork Ridge Trail crossing of Deep Creek at junction with Deep Creek Trail en 0.4 o P 416 D w IN r e o k Forney Creek Trail** seven crossings G TENNESSEE TA n a nWEB a N g B p Gunter Fork Trail** five crossingsU S OUNTAIN 0.1 Exit 451 O M 32 Hannah Mountain Trail** justM before Abrams Falls Trail L i NORTH CAROLINA tt Jonas Creek Trail near Forney Creek le Little River Trail near campsite #30 PIGEON FORGE C 7.4 Long Hungry Ridge Trail both sides of campsite #92 Pig o 35 Davenport eo s MOUNTAIN n b mere MARYVILLE Lost Cove Trail near Lakeshore Trail junction y Cam r Trail Gap nt Waterville R Pittman u C 1.9 Meigs Creek Trail 18 crossings k i o h E v Big Creek E e M 1.0 e B W e Mt HO e Center 73 Mount s L Noland Creek Trail** both sides of campsite #62 r r 321 Hen Wallow Falls t 2.1 HI C r Cammerer n C Cammerer C r e u 321 1.2 e Panther Creek Trail at Middle Prong Trail junction 0.6 t e w Trail Br Tr k o L Pole Road Creek Trail near Deep Creek Trail M 6.6 2.3 321 a 34 321 il Rabbit Creek Trail at the Abrams Falls Trailhead d G ra Gatlinburg Welcome Center 5.8 d ab T National Park ServiceNational Park U.S.