Prime Pagine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hammond Sk1-73

Originally printed in the October 2013 issue of Keyboard Magazine. Reprinted with the permission of the Publishers of Keyboard Maga- zine. Copyright 2008 NewBay Media, LLC. All rights reserved. Keyboard Magazine is a Music Player Network publication, 1111 Bayhill Dr., St. 125, San Bruno, CA 94066. T. 650.238.0300. Subscribe at www.musicplayer.com REVIEW SYNTH » CLONEWHEEL » VIRTUAL PIANO » STANDS » MASTERING » APP HAMMOND SK1-73 BY BRIAN HO HAMMOND’S SK SERIES HAS SET A NEW PORTABILITY STANDARD FOR DRAWBAR that you’re using for pianos, EPs, Clavs, strings, organs that also function as versatile stage keyboards in virtue of having a comple- and other sounds. ment of non-organ sounds that can be split and layered with the drawbar section. Even though there isn’t a button that causes Where the original SK1 had 61 keys and the SK2 added a second manual, the new the entire keyboard to play only the lower organ SK1-73 and SK1-88 aim for musicians looking for the same sonic capabilities in a part—useful if you want to switch between solo single-slab form factor that’s more akin to a stage piano. I got to use the 73-key and comping sounds without disturbing the sin- model on several gigs and was very pleased with its sound and performance. gle set of drawbars—I found a cool workaround. Simply create a “Favorite” (Hammond’s term for Keyboard Feel they’ll stand next to anything out there and not presets that save the entire state of the instru- I find that a 61-note keyboard is often too small leave you or the audience wanting for realism. -

MOX6/MOX8 Data List 2 Voice List

Data List Table of Contents Voice List .................................................2 Drum Voice List .....................................11 Drum Voice Name List ............................ 11 Drum Kit Assign List ............................... 12 Waveform List .......................................29 Performance List ...................................34 Master Assign List .................................36 Arpeggio Type List ................................37 Effect Type List ......................................78 Effect Parameter List .............................79 Effect Preset List ...................................87 Effect Data Assign Table .......................89 Mixing Template List .............................97 Remote Control Assignments ................98 Control List ............................................99 MIDI Data Format ................................100 MIDI Data Table ..................................104 MIDI Implementation Chart ..................127 EN Voice List PRE1 (MSB=63, LSB=0) Category Category Number Voice Name Element Number Voice Name Element Main Sub Main Sub 1 A01 Full Concert Grand Piano APno 2 65 E01 Dyno Wurli Keys EP 2 2 A02 Rock Grand Piano Piano Modrn 2 66 E02 Analog Piano Keys Synth 2 3 A03 Mellow Grand Piano Piano APno 2 67 E03 AhrAmI Keys Synth 2 4 A04 Glasgow Piano APno 4 68 E04 Electro Piano Keys EP 2 5 A05 Romantic Piano Piano APno 2 69 E05 Transistor Piano Keys Synth 2 6 A06 Aggressive Grand Piano Modrn 3 70 E06 EP Pad Keys EP 3 7 A07 Tacky Piano Modrn 2 71 E07 DX Pad -

Hammond Jazz Empfehlungen

Hammond Jazz Empfehlungen Vorname Name Album Label B-3in' Organ Jazz 32Jazz George Benson It's Uptown Columbia George Benson The George Benson Cookbook Columbia George/"Brother" Jack Benson/McDuff George Benson & Jack McDuff Prestige Pat Bianchi East Coast Roots Jazzed Media Earl Bostic Complete Quintet Recordings Lonehilljazz Terence Brewer Groovin' Wes StrongBrewMusic Gloria Coleman Sweet Missy Doodlin' Records Linda Dachtyl For Hep Cats Chicken Coup Wild Bill Davis The Zurich Concert Jazz Connaisseur Deep Blue Organ Trio Wonderful Origin Records Moe Denham The Soul Jazz Sessions Thortch Recordings Joey DeFrancesco All About My Girl Muse Records Joey DeFrancesco All or Nothing at All Big Mo Joey DeFrancesco Ballads and Blues Concord Papa John DeFrancesco Desert Heat High Note Joey DeFrancesco Goodfellas Concord Joey DeFrancesco Joey DeFrancesco plays Sinatra his way High Note Joey DeFrancesco Legacy Concord Joey DeFrancesco One For Rudy High Note Joey DeFrancesco Plays Sinatra His Way High Note Joey DeFrancesco Singin' and Swingin' Concord Joey DeFrancesco The Champ Round 2 High Note Joey DeFrancesco The Philadelphia Connection High Note Bob De Vos Breaking the ice Savant Barbara Dennerlein Junkanoo Verve www.b-tonic.ch Seite 1 von 7 Hammond Jazz Empfehlungen Barbara Dennerlein Love Letters Bebab Lou Donaldson Everything I Play Is Funky Blue Note Lou Donaldson Good Gracious! Blue Note Lou Donaldson Here 'Tis Blue Note Lou Donaldson Midnight Creeper Blue Note Lou Donaldson The Natural Soul Blue Note Charles Earland Cookin' With the Mighty -

Big Organ Trio Has Emerged As a Band with a Truly Unique Voice

Band Contact: Booking Contact: [email protected] Jim Wadsworth Productions 330-405-9075 [email protected] Bio "This isn 't your standard jazz trio", remarked Jambands.com. Since its inception in 2004, Big Organ Trio has emerged as a band with a truly unique voice. Their acclaimed debut CD was released in 2006 and has led to thousands of music and merchandise sales in addition to concerts across the U.S. and internationally. B.O.T. 's groundbreaking approach to the organ trio format has drawn the attention of Keyboard Magazine, who featured the band in 2006, and many of the world 's greatest Hammond players. The combo has played with Keith Emerson (Emerson, Lake, & Palmer) and shared the stage with Melvin Seals (Jerry Garcia Band). Gregg Rolie (vocalist/organist from Santana) and Tony Monaco (world renowned jazz organist) have also commented on the trio 's fresh and inventive sound. High profile performances at major music festivals such as 10,000 Lakes Festival (MN) and Fillmore Jazz Festival (SF) as well as shows with the likes of Robby Krieger (The Doors), Umphrey 's McGee, Leo Nocentelli (The Meters), and Stanton Moore (Galactic) have helped fuel the buzz. With an exploding fan-base worldwide and gigantic internet presence the band has won fan voting polls on websites such as Jambands.com and seen their debut album become the top selling Hammond Organ album on CDbaby.com. B.O.T. music can also be heard on networks such as E! Channel and radio programs around the globe. Mike Mangan (Hammond B3 Organ), Bernie Bauer (Electric Bass), and Brett McConnell (Drums) all share a great love and respect for the old school spirit of blues and jazz improvisation. -

MOXF6/MOXF8 Data List 2 Voice List

Data List Table of Contents Voice List..................................................2 Drum Voice List ......................................12 Drum Voice Name List............................. 12 Drum Kit Assign List ................................ 13 Waveform List ........................................32 Performance List ....................................45 Master Assign List ..................................47 Arpeggio Type List .................................48 Effect Type List.......................................97 Effect Parameter List..............................98 Effect Preset List ..................................106 Effect Data Assign Table......................108 Mixing Template List ............................116 Remote Control Assignments...............117 Control List ...........................................118 MIDI Data Format.................................119 MIDI Data Table ...................................123 MIDI Implementation Chart...................146 EN Voice List PRE1 (MSB=63, LSB=0) Category Category Number Voice Name Element Number Voice Name Element Main Sub Main Sub 1 A01 Full Concert Grand Piano APno 2 65 E01 Dyno Wurli Keys EP 2 2 A02 Rock Grand Piano Piano Modrn 2 66 E02 Analog Piano Keys Synth 2 3 A03 Mellow Grand Piano Piano APno 2 67 E03 AhrAmI Keys Synth 2 4 A04 Glasgow Piano APno 4 68 E04 Electro Piano Keys EP 2 5 A05 Romantic Piano Piano APno 2 69 E05 Transistor Piano Keys Synth 2 6 A06 Aggressive Grand Piano Modrn 3 70 E06 EP Pad Keys EP 3 7 A07 Tacky Piano Modrn 2 71 E07 -

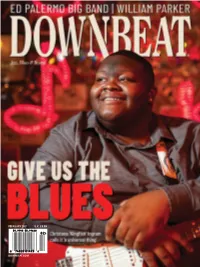

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Sunday, August 10, 2014 Plaza De César Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Event Info: Summerfest.Sanjosejazz.Org

***For Immediate Release*** Media Contact: Jesse P. Cutler JP Cutler Media 415.826.9516 [email protected] Friday, August 8 - Sunday, August 10, 2014 Plaza de César Chavez Park, Downtown San Jose, CA Event Info: summerfest.sanjosejazz.org Second Line-Up Announcement: Bootsy Collins, Con Funk Shun, Pacific Mambo Orchestra, Donald Harrison w/ Special Guest Kevin Harris, Catherine Russell, Snarky Puppy, Soul Rebels, Jerry González and the Fort Apache Band, Jimmy Bosch, Pedrito Martinez Group featuring Ariacne Trujillo, Gypsy Allstars, Andre Thierry, Hot Club of Detroit, San Jose Taiko with Bangerz, Edgardo Cambón y Su Conjunto LaTiDo, Conjunto Chappottín y Sus Estrellas, Aaron Lington Quintet Plays the Music of Paul Simon, Viento de Agua, Otonowa Project, Monty Alexander and the Harlem-Kingston Express, Jesus Diaz y Su QBA, Isaiah Pickett Band, Alex Hahn and the Blue Riders, The 6th Annual Jazz Organ Fellowship, The Delgado Brothers, Beaufunk, Michael Bellar & the AS-IS Ensemble, Tango Jazz Quartet, Denise Perrier Trio with Houston Person, CJ Chenier and the Red Hot Louisiana Band, Leon Joyce Jr. Trio, John Worley's Mo-Chi Sextet: The Miles of Blue Project, San Jose Jazz High School All Stars "The San Jose Jazz Summer Fest is one of the most popular music festivals in the Bay Area." -KCBS "San Jose Jazz's Summer Fest proved to be a highlight of the summer for downtown yet again." -San Jose Mercury News "San Jose Jazz deserves a good deal of credit for spotting some of the region's most exciting artists long before they're headliners." -Andy Gilbert, San Jose Mercury News "…the festival continues to up the ante with the roster of about 80 performers that encompasses everything from marquee names to unique up and comers, and both national and local acts...." -Silicon Valley Community Newspapers San Jose, CA -- May 22, 2014 -- San Jose Jazz announces today additions to its artist line-up for the 25th Anniversary San Jose Jazz Summer Fest 2014, Silicon Valley's premier annual music event. -

Download Download

JOURNAL 0 F THE AMERICAN THEATRE ORGAN SOCIETY JULY | AUGUST 2012 -~ · . •··· ' , , , ' ' ..••. •. .•. • ..' ·· ·•·•·4- ..., , ' ········I ··• ·I ·I· ·I ··I I ~· ....• ·o.·e· . • ••••••• • •• ,, /. ,. ,; - ,~,. , . ' . / ,. • : '! .• J ~ :·.: ' . CLIFF HIPKINS KEN CROME WALKER TECHNICAL COMPANY ROB RICHARDS RESIDENCE ORGAN CONSOLE CONTROL SYSTEM & VOICES TONAL CONSULTANT 5M/ /JD RANK fl/;e1 WALJ<ER. Digital UNIT0R.CHESTRA ;· ,.,: ~I. • .. THEATRE ORGAN JULY | AUGUST 2012 Volume 54 | Number 4 FEATURES Radio City Music Hall 12 Gala: The Rest of the Story The Society of Theatre 16 Organists Technical 20 Experience Taylor Trimby’s Virtual 24 Wurlitzer/Marr & Colton The Best Show in 29 Las Vegas Yes Virginia, Young 38 Kids Can Like the Theatre Organ The Virginia 46 Theatre DEPARTMENTS 3 Vox Humana 4 President’s Message 6 News & Notes 10 Letters 11 Vox Pops Phil Maloof at his Roxy Kimball console (Photographs ©2012 Kim Cochrane, DesertSpiritPhotography.com) 48 For the Records 50 Chapter News On the Cover: The Roxy builders plate was somewhat more ornate 60 Around the Circuit on this unique console than what was typical of Kimball (Photographs ©2012 Kim Cochrane, DesertSpiritPhotography.com) 64 Closing Chord THEATRE ORGAN (ISSN 0040-5531) is published bimonthly by the American Theatre Organ 68 Meeting Minutes Society, Inc., 7800 Laguna Vega Drive, Elk Grove, California 95758. Periodicals Postage Paid at Elk Grove, California and at additional mailing offices. Annual subscription of $33.00 paid from members’ dues. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to THEATRE ORGAN, c/o ATOS Membership Office, P.O. Box 5327, Fullerton, California 92838, [email protected]. www.atos.org JULY | AUGUST 2012 1 Journal of the American Theatre Organ Society Library of Congress Catalog Number ML 1T 334 (ISSN 0040-5531) Printed in U.S.A. -

Blackbox @ the Edye Jazz

blackbox @ the edye jazz. blues. grooves. Curated and Hosted by The Reverend Shawn Amos FRI / DEC 13 / 8:00 PM Produced by The Broad Stage and Put Together Music Rumproller Organ Trio Carey Frank HAMMOND B3 Kevin Stevens DRUMS James Achor GUITAR SPECIAL GUESTS Woody Mankowski SAXOPHONE AND VOCALS Femi Knight VOCALS Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. There will be no intermission. Jazz & Blues at The Broad Stage made possible by a generous gift from Richard & Lisa Kendall. blackbox @ the edye at The Broad Stage made possible by a generous gift from Ann Petersen & Leslie Pam. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 4 ABOUT THE ARTISTS CURATOR NOTE BIO When not touring with Social Distortion or Tedeschi Trucks Band, Welcome back to the blackbox. RUMPROLLER ORGAN TRIO is centered on the Hammond B3 Organ, a staple B3 virtuoso Carey Frank mans the This time around, we’re digging a bit controls of the organ. James Achor deeper and doing some serious time of American music from churches to nightclubs, living rooms to ballparks. of ‘90s swing revival kings Royal travel. We’ll visit 1920s Harlem, take Crown Revue plays guitar and groove- a turn downtown for some hard bop, Capable of a mellow whisper or a raucous roar, the many voices of master/Rumproller-founder Kevin travel west for some cool jazz and Stevens is on drums. listen to 1960s-era vocals. I’ll join you the B3, along with guitar and drums, at the end of the line for some juke lend a soulful tinge to any song. The Forrest “Woody” Mankowski has been joint blues. -

Woodstock Villager Mailed Free to Requesting Homes in Eastford, Pomfret & Woodstock Vol

ERSAR IV Y N N A A A N N N N I I V V Y Y E E R R R R A A S S WOODSTOCK VILLAGER Mailed free to requesting homes in Eastford, Pomfret & Woodstock Vol. X, No. 19 Complimentary to homes by request (860) 928-1818/e-mail: [email protected] Friday, February 5, 2016 Tell me Town debuts a story new website EFFORT AIMED AT KEEPING I think my affinity for a good narra- tive is rubbing off on my son. PEOPLE ‘MORE INFORMED’ There are many bedtime rituals one BY JASON BLEAU can have, and each family has their NEWS STAFF WRITER own, but it’s funny to see how my THOMPSON — Over 4-year-old son is so much like his old the past few years the man sometimes. Town of Thompson It’s like clockwork. After getting has gone through more into his “jammies,” brushing his changes to its town teeth, taking a few sips of water and website than most tucking himself into his bed, the one communities in north- question never fails to escape his lips. eastern Connecticut “Daddy, can you tell me a story?” combined, in an effort It’s a tradition that’s lasted nearly Courtesy photo to bring top-notch ser- two years now — no books, just a made- vice to the community. up-on- Woodstock Academy Vocational Technology Teacher Keith Landin and the stu- dents of his new “Explorations in Woodworking” course show off the guitars made As of December, yet the- THE in the class. -

Masters Thesis

Hammond Technique and Methods: Music Written for the Hammond Organ JESSE WHITELEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO SEPTEMBER 2013 © JESSE WHITELEY, 2013 Abstract The following thesis is made up of four original compositions written between February and September of 2012, with emphasis on the Hammond Organ in the context of jazz and rhythm and blues ensembles. The pieces of music were designed to feature the organ as the lead instrument in order to highlight various playing techniques that are specific to the Hammond Organ within these genres. In addition to my own music and an explanation and analysis of my work, the writing will provide a historical overview of organists I have chosen to highlight as influences to provide a framework for each piece of music. In order to aid this discussion of what has been an under-theorized instrument and performance tradition, I have sought out active contemporary organists to discuss their creative practices on the Hammond, as well as their insight into the notable organists of the past. Finally, of particular interest to me in this thesis is the emphasis on the Hammond Organ as an electric instrument, and the unique musical textures that are possible through the exploitation of the multiple controls that are integral to the instrument's construction. An audio recording of each piece accompanies the scores that are included. ii Acknowledgements A big thanks to my supervisor Rob Bowman for being the perfect person to work on this project with, for his good advice, resources, and above all - enthusiasm, which has charged me up in the writing of this, multiple times. -

CLINE-DISSERTATION.Pdf (2.391Mb)

Copyright by John F. Cline 2012 The Dissertation Committee for John F. Cline Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Steven Hoelscher Randolph Lewis Karl Hagstrom Miller Shirley Thompson Permanent Underground: Radical Sounds and Social Formations in 20th Century American Musicking by John F. Cline, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my mother and father, Gary and Linda Cline. Without their generous hearts, tolerant ears, and (occasionally) open pocketbooks, I would have never made it this far, in any endeavor. A second, related dedication goes out to my siblings, Nicholas and Elizabeth. We all get the help we need when we need it most, don’t we? Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation supervisor, Mark Smith. Even though we don’t necessarily work on the same kinds of topics, I’ve always appreciated his patient advice. I’m sure he’d be loath to use the word “wisdom,” but his open mind combined with ample, sometimes non-academic experience provided reassurances when they were needed most. Following closely on Mark’s heels is Karl Miller. Although not technically my supervisor, his generosity with his time and his always valuable (if sometimes painful) feedback during the dissertation writing process was absolutely essential to the development of the project, especially while Mark was abroad on a Fulbright.