Jazz Organ History 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Grant Green Grantstand Mp3, Flac, Wma

Grant Green Grantstand mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Grantstand Country: US Released: 1961 Style: Soul-Jazz, Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1122 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1402 mb WMA version RAR size: 1247 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 707 Other Formats: WAV MP3 MP1 MIDI AIFF VQF DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Grantstand A1 Written-By – Green* My Funny Valentine A2 Written-By – Rodgers-Hart* Blues In Maude's Flat B1 Written-By – Green* Old Folks B2 Written-By – Hill*, Robison* Companies, etc. Published By – Groove Music Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Drums – Al Harewood Guitar – Grant Green Liner Notes – Nat Hentoff Organ – Jack McDuff* Photography By [Cover Photo] – Francis Wolff Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By] – Rudy Van Gelder Tenor Saxophone, Flute – Yusef Lateef Notes Recorded on August 1, 1961, Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Blue Note Records Inc., 43 W 61st St., New York 23 (Adress on Back Cover) Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A Label): BN 4086-A Matrix / Runout (Side B Label): BN 4086-B Matrix / Runout (Side A Runout etched): BN-LP-4086-A Matrix / Runout (Side B Runout etched): BN-LP-4086-B Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Blue Grant Grantstand (LP, BN 84086, BN 4086 Note, BN 84086, BN 4086 Japan 1992 Green Album, Ltd, RE) Blue Note Grant Grantstand (CD, 7243 5 80913 2 8 Blue Note 7243 5 80913 2 8 US 2003 Green Album, RE, RM) Grantstand (CD, Blue TOCJ-9244, -

Discography of the Mainstream Label

Discography of the Mainstream Label Mainstream was founded in 1964 by Bob Shad, and in its early history reissued material from Commodore Records and Time Records in addition to some new jazz material. The label released Big Brother & the Holding Company's first material in 1967, as well as The Amboy Dukes' first albums, whose guitarist, Ted Nugent, would become a successful solo artist in the 1970s. Shad died in 1985, and his daughter, Tamara Shad, licensed its back catalogue for reissues. In 1991 it was resurrected in order to reissue much of its holdings on compact disc, and in 1993, it was purchased by Sony subsidiary Legacy Records. 56000/6000 Series 56000 mono, S 6000 stereo - The Commodore Recordings 1939, 1944 - Billy Holiday [1964] Strange Fruit/She’s Funny That Way/Fine and Mellow/Embraceable You/I’ll Get By//Lover Come Back to Me/I Cover the Waterfront/Yesterdays/I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues/I’ll Be Seeing You 56001 mono, S 6001 stereo - Begin the Beguine - Eddie Heywood [1964] Begin the Beguine/Downtown Cafe Boogie/I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me/Carry Me Back to Old Virginny/Uptown Cafe Boogie/Love Me Or Leave Me/Lover Man/Save Your Sorrow 56002 mono, S 6002 stereo - Influence of Five - Hawkins, Young & Others [1964] Smack/My Ideal/Indiana/These Foolish Things/Memories Of You/I Got Rhythm/Way Down Yonder In New Orleans/Stardust/Sittin' In/Just A Riff 56003 mono, S 6003 stereo - Dixieland-New Orleans - Teagarden, Davison & Others [1964] That’s A- Plenty/Panama/Ugly Chile/Riverboat Shuffle/Royal Garden Blues/Clarinet -

Lou Donaldson the Natural Soul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lou Donaldson The Natural Soul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Natural Soul Country: US Released: 1986 Style: Soul-Jazz, Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1767 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1621 mb WMA version RAR size: 1543 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 259 Other Formats: MP3 VOC WMA MP4 DTS DXD AA Tracklist Hide Credits Funky Mama A1 9:05 Written-By – John Patton Love Walked In A2 5:10 Written-By – George & Ira Gershwin Spaceman Twist A3 5:35 Written-By – Lou Donaldson Sow Belly Blues B1 10:11 Written-By – Lou Donaldson That's All B2 5:33 Written-By – Alan Brandt, Bob Haymes Nice 'N Greasy B3 5:24 Written-By – Johnny Acea Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Manhattan Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Manhattan Records Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Alto Saxophone – Lou Donaldson Design [Cover] – Reid Miles Drums – Ben Dixon Guitar – Grant Green Liner Notes – Del Shields Organ – John Patton Photography By [Cover Photo] – Ronnie Brathwaite Producer – Alfred Lion Recorded By [Recording By] – Rudy Van Gelder Trumpet – Tommy Turrentine Notes Recorded on May 9, 1962. 1986 Manhattan Records, a division of Capitol Records, Inc. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Natural Soul (LP, BLP 4108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note BLP 4108 US 1963 Album, Mono) The Natural Soul (CD, CDP 7 84108 2 Lou Donaldson Blue Note CDP 7 84108 2 US 1989 Album, RE) TOCJ-7176, The Natural Soul (CD, Blue Note, TOCJ-7176, Lou Donaldson Japan 2008 BST-84108 Album, RE) Blue Note BST-84108 The Natural Soul 4BN 84108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note 4BN 84108 US 1986 (Cass, Album, RM) The Natural Soul (LP, BST-84108 Lou Donaldson Blue Note BST-84108 US 1973 Album, RE) Related Music albums to The Natural Soul by Lou Donaldson Lou Donaldson - Mr. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

Booker Ervin the Song Book Mp3, Flac, Wma

Booker Ervin The Song Book mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Song Book Country: US Released: 1993 Style: Post Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1466 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1778 mb WMA version RAR size: 1408 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 541 Other Formats: TTA DTS DXD AU MP4 AC3 AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits The Lamp Is Low 1 7:13 Written-By – Shefter*, Ravel*, Parish*, DeRose* Come Sunday 2 5:37 Written-By – Duke Ellington All The Things You Are 3 5:19 Written-By – Kern*, Hammerstein* Just Friends 4 5:53 Written-By – Klenner*, Lewis* Yesterdays 5 7:42 Written-By – Kern*, Harbach* Our Love Is Here To Stay 6 6:25 Written-By – Gershwin*, Gershwin* Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Fantasy, Inc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Remastered At – Fantasy Studios Credits Bass – Richard Davis Drums – Alan Dawson Engineer [Recording Engineer] – Rudy Van Gelder Liner Notes [May 1964] – Dan Morgenstern Piano – Tommy Flanagan Producer, Design [Cover], Photography By – Don Schlitten Remastered By [Digital Remastering, 1993] – Phil De Lancie Tenor Saxophone – Booker Ervin Notes Recorded in Englewood Cliffs, NJ; February 27, 1964 Digital remastering, 1993 (Fantasy Studios, Berkeley) © 1993, Fantasy, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 02521867792 Other (SPARS Code): AAD Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year PR 7318, PRST Booker The Song Book Prestige, PR 7318, PRST US 1964 7318 Ervin (LP, Album) Prestige 7318 The Song Book Booker VICJ-41556 (CD, Album, -

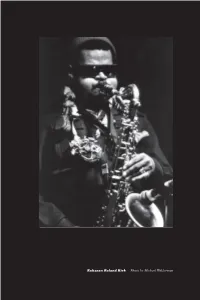

60 / Running Head

60 / running head RahsaRahsaaRahsaan Roland Kirk Photo by Michael Wilderman monstrosioso 1965: The Creeper The fussy encyclopedic gravity of the Hammond B-3 overcome and the electric organ lofted to hard-bop orbit, still trailing diapasons of his mother’s church music and the boogie-woogie tap-dance routines of his father’s band—The Incredible Jimmy Smith proclaimed the block letters on a score of albums since the 1956 breakout recordings on Blue Note, those words celebrating a nearly miraculous mating of technology and soul. The thing had first stirred to life at a club in Atlantic City where he heard Wild Bill Davis make the Hammond roar like a big wave. It was a monster, upsurged through chocked, choppy chords and backwashed through rilling legatos, wattage enough there to power the entire Basie band. Davis was gruff, brash, gloriously loud, a bumptious lumbering at- tack, great swoops down on the keys and shameless ripsaw goosings of reverb and tremolo, the organ not so much singing as signaling, the music stripped to pure swelling impulse. For a piano player schooled in the over- brimming muscular lines of Art Tatum and the stabbing, nervous prances of Bud Powell, it was almost risible, the goddamned wired-up thing rock- ing on stage like a gurgling showboat. Fats Waller on “Jitterbug Waltz” coaxed over the organ with a percolating finesse as if running a trapeze artist up a swaying wire, but Davis almost seemed clumsy by design, as if in awe of the organ’s powers yet unable to forego provoking them. -

Saxophonist & Composer PHILLIP JOHNSTON NEW RELEASES

ever needing to hear another take on “I’m In The Mood a lute with a short fingerboard and 11-13 strings, For Love”? Yeah, probably, but this one is fine. “And traditionally used in Arabian, Egyptian, Jewish, Now The Queen” is much more interesting; Goldings Palestinian, Iraqi, Persian, Turkish and Armenian music. opens it with some deeply unsettling noises that could In the jazz world, the oud has been explored by Ahmed come off a Supersilent album, as Stewart bows his Abdul-Malik, Rabih Abou-Khalil and Anouar Brahem. cymbals and rattles his kit like he’s stress-testing the Canadian guitarist Gordon Grdina comes forth mounting hardware. Although the piece has a powerful with a strong, individual voice and the ensemble is melody, it appears as a series of unexpected surges, assimilated like it’s a new discovery of something punctuation at the end of long bursts of disjointed around for a long time. Percussionist Hamin Honari Toy Tunes weirdness. “Toy Tune” builds on a deceptively simple provides extraordinary accompaniment, especially for Larry Goldings/Peter Bernstein/Bill Stewart (Pirouet) head, allowing the trio to meander around for seven listeners used to the American drumset. As he is by Phil Freeman minutes, making it the longest track. “Maybe” is an credited on tombak and daf (traditional Iranian drums), ideal closer, a gentle tune delivered without disruption one wonders from where all of his nuanced sounds Organ player Larry Goldings, guitarist Peter Bernstein or undue exuberance, bringing the mood down to a emanate. The texture and timbre of Honari’s percussion and drummer Bill Stewart first convened as a trio for soothing simmer as the music fades away. -

Lou Donaldson

BIO LOU DONALDSON --------------------------------------- "My first impulse is always to describe Lou Donaldson as the greatest alto saxophonist in the world." -- Will Friedwald, New York Sun Jazz critics agree that “Sweet Poppa Lou” Donaldson is one of the greatest alto saxophonists of all time. He began his career as a bandleader with Blue Note Records in 1952 and, already at age 25, had found his sound, though it would continue to sweeten over the years -- earning him his famed nickname --“Sweet Poppa Lou.” He made a series of classic records for Blue Note Records in the 50’s and takes pride in having showcased many musicians who made their first records as sidemen for him: Clifford Brown, Grant Green, Blue Mitchell, Donald Byrd, Ray Barretto, Horace Parlan, John Patton, Charles Earland, Al Harewood, Herman Foster, Peck Morrison, Dave Bailey, Leon Spencer, Idris Muhammad, and others. After also making some excellent recordings for Cadet and Argo Records in the early 60s, Lou’s return to Blue Note in 1967 was marked by one of his most famous recordings, Alligator Bogaloo. Lou’s hits on the label are still high demand favorites and, today at age 93, he is its oldest musician from that notable era of jazz. Though now retired, Lou continues to receive applause from fans worldwide who call and write to tell him how much they enjoy his soulful, thoroughly swinging, and steeped in the blues appearances over the years and still love listening to his recordings. Lou is the recipient of countless honors and awards for his significant contributions to jazz — America’s “classical music.”. -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5.