Frequency and Characteristics of Arctic Tundra Fires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada GREENLAND 80°W

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-B Module 7 70°N 30°W 20°W 170°W 180° 70°N 160°W Canada GREENLAND 80°W 90°W 150°W 100°W (DENMARK) 120°W 140°W 110°W 60°W 130°W 70°W ARCTIC Essential Question OCEANDo Canada’s many regional differences strengthen or weaken the country? Alaska Baffin 160°W (UNITED STATES) Bay ic ct r le Y A c ir u C k o National capital n M R a 60°N Provincial capital . c k e Other cities n 150°W z 0 200 400 Miles i Iqaluit 60°N e 50°N R YUKON . 0 200 400 Kilometers Labrador Projection: Lambert Azimuthal TERRITORY NUNAVUT Equal-Area NORTHWEST Sea Whitehorse TERRITORIES Yellowknife NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Hudson N A Bay ATLANTIC 140°W W E St. John’s OCEAN 40°W BRITISH H C 40°N COLUMBIA T QUEBEC HMH Middle School World Geography A MANITOBA 50°N ALBERTA K MS_SNLESE668737_059M_K.ai . S PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND R Edmonton A r Canada legend n N e a S chew E s kat Lake a as . Charlottetown r S R Winnipeg F Color Alts Vancouver Calgary ONTARIO Fredericton W S Island NOVA SCOTIA 50°WFirst proof: 3/20/17 Regina Halifax Vancouver Quebec . R 2nd proof: 4/6/17 e c Final: 4/12/17 Victoria Winnipeg Montreal n 130°W e NEW BRUNSWICK Lake r w Huron a Ottawa L PACIFIC . t S OCEAN Lake 60°W Superior Toronto Lake Lake Ontario UNITED STATES Lake Michigan Windsor 100°W Erie 90°W 40°N 80°W 70°W 120°W 110°W In this module, you will learn about Canada, our neighbor to the north, Explore ONLINE! including its history, diverse culture, and natural beauty and resources. -

Assessing Snow Phenology Over the Large Part of Eurasia Using Satellite Observations from 2000 to 2016

remote sensing Article Assessing Snow Phenology over the Large Part of Eurasia Using Satellite Observations from 2000 to 2016 Yanhua Sun 1, Tingjun Zhang 1,2,*, Yijing Liu 1, Wenyu Zhao 1 and Xiaodong Huang 3 1 Key Laboratory of West China’s Environment (DOE), College of Earth and Environment Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (Y.S.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (W.Z.) 2 University Corporation for Polar Research, Beijing 100875, China 3 School of Geographical Sciences, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-138-9337-2955 Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 23 June 2020; Published: 26 June 2020 Abstract: Snow plays an important role in meteorological, hydrological and ecological processes, and snow phenology variation is critical for improved understanding of climate feedback on snow cover. The main purpose of the study is to explore spatial-temporal changes and variabilities of the extent, timing and duration, as well as phenology of seasonal snow cover across the large part of Eurasia from 2000 through 2016 using a Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud-free snow product produced in this study. The results indicate that there are no significant positive or negative interannual trends of snow cover extent (SCE) from 2000 to 2016, but there are large seasonal differences. SCE shows a significant negative trend in spring (p = 0.01) and a positive trend in winter. The stable snow cover areas accounting for 78.8% of the large part of Eurasia, are mainly located north of latitude 45◦ N and in the mountainous areas. -

Determining Carbon Stocks in Cryosols Using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database

Permafrost, Phillips, Springman & Arenson (eds) © 2003 Swets & Zeitlinger, Lisse, ISBN 90 5809 582 7 Determining carbon stocks in Cryosols using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database C. Tarnocai Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada J. Kimble USDA-NRCS-NSSC, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA G. Broll Institute of Landscape Ecology, University of Muenster, Muenster, Germany ABSTRACT: The distribution of Cryosols and their carbon content and mass in the northern circumpolar area were estimated by using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database (NMLSD). Using this database, it was estimated that, in the Northern Hemisphere, Cryosols cover approximately 7769 ϫ 103 km2 and contain approxi- mately 119 Gt (surface, 0–30 cm) and 268 Gt (total, 0–100 cm) of soil organic carbon. The 268 Gt organic carbon is approximately 16% of the world’s soil organic carbon. Organic Cryosols were found to have the highest soil organic carbon mass at both depth ranges while Static Cryosols had the lowest. The accuracy of these carbon val- ues is variable and depends on the information available for the area. Since these soils contain a significant por- tion of the Earth’s soil organic carbon and will probably be the soils most affected by climate warming, new data is required so that more accurate estimates of their carbon budget can be made. 1 INTRODUCTION which is in Arc/Info format, the Soils of Northern and Mid Latitudes (Tarnocai et al. 2002a) and Northern Soils are the largest source of organic carbon in ter- Circumpolar Soils (Tarnocai et al. 2002b) maps were restrial ecosystems. -

The Different Stratospheric Influence on Cold-Extremes in Eurasia and North America

The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Kretschmer, M. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2756- 9526, Cohen, J., Matthias, V., Runge, J. and Coumou, D. (2018) The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 1 (1). ISSN 2397-3722 doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/92433/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online www.nature.com/npjclimatsci ARTICLE OPEN The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America Marlene Kretschmer1,2, Judah Cohen3, Vivien Matthias1, Jakob Runge4 and Dim Coumou1,5 The stratospheric polar vortex can influence the tropospheric circulation and thereby winter weather in the mid-latitudes. Weak vortex states, often associated with sudden stratospheric warmings (SSW), have been shown to increase the risk of cold-spells especially over Eurasia, but its role for North American winters is less clear. -

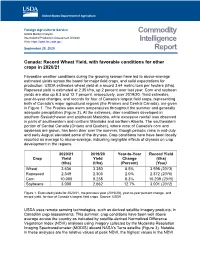

Canada: Record Wheat Yield, with Favorable Conditions for Other Crops in 2020/21

Foreign Agricultural Service Global Market Analysis Commodity International Production Assessment Division Web: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov Intelligence September 29, 2020 Report Canada: Record Wheat Yield, with favorable conditions for other crops in 2020/21 Favorable weather conditions during the growing season have led to above-average estimated yields across the board for major field crops, and solid expectations for production. USDA estimates wheat yield at a record 3.64 metric tons per hectare (t/ha). Rapeseed yield is estimated at 2.35 t/ha, up 2 percent over last year. Corn and soybean yields are also up 8.3 and 12.7 percent, respectively, over 2019/20. Yield estimates, year-to-year changes, and records for four of Canada’s largest field crops, representing both of Canada’s major agricultural regions (the Prairies and Central Canada), are given in Figure 1. The Prairies saw warm temperatures throughout the summer and generally adequate precipitation (Figure 2). At the extremes, drier conditions developed in southern Saskatchewan and southeast Manitoba, while excessive rainfall was observed in parts of southwestern and northern Manitoba and northern Alberta. The southeastern portion of Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec), where most of Canada's corn and soybeans are grown, has been drier over the summer, though periodic rains in mid-July and early August aleviated some of the dryness. Crop conditions here have been locally reported as average to above-average, indicating negligible effects of dryness on crop development in the regions. 2020/21 2019/20 Year-to-Year Record Yield Crop Yield Yield Change (t/ha) (t/ha) (t/ha) (Percent) (Year) Wheat 3.636 3.350 8.5% 3.598 (2013) Rapeseed 2.349 2.303 2.0% 2.372 (2016) Corn 10.000 9.238 8.3% 10.209 (2015) Soybeans 3.000 2.662 12.7% 3.001 (2012) Figure 1. -

TEACHER NOTES 6TH GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Latin America and Canada - HISTORICAL UNDERSTANDINGS - SS6H1 - Explain Conflict and Change in Latin America

6th Grade Social Studies Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies The Teacher Notes were developed to help teachers understand the depth and breadth of the standards. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Please remember that the goal of Social Studies is not to have students memorize laundry lists of facts, but rather to help them understand the world around them so they can analyze issues, solve problems, think critically, and become informed citizens. Children’s Literature: A list of book titles aligned to the 6th-12th Grade Social Studies GSE may be found at the Georgia Council for the Social Studies website: http://www.gcss.net/uploads/files/Childrens-Literature-Grades-6-to-12.pdf TEACHER NOTES 6TH GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Latin America and Canada - HISTORICAL UNDERSTANDINGS - SS6H1 - Explain conflict and change in Latin America. Standard H1 explores the contemporary events of Latin American history which have shaped the current geopolitical and socioeconomic climate of the region. As with all 6th grade historical standards, it is not intended to serve as an exhaustive history of the region, but rather a snapshot of major events and historical trends that help explain the current state of Latin American affairs. In this regard, special attention is given to the transformative influence of Spanish and Portuguese exploration and colonization in the region, the cultural and economic impact of the transatlantic slave trade, the geopolitical impact of Cuba’s 1959 communist revolution, and the status of U.S. -

Canada's Arctic Marine Atlas

Lincoln Sea Hall Basin MARINE ATLAS ARCTIC CANADA’S GREENLAND Ellesmere Island Kane Basin Nares Strait N nd ansen Sou s d Axel n Sve Heiberg rdr a up Island l Ch ann North CANADA’S s el I Pea Water ry Ch a h nnel Massey t Sou Baffin e Amund nd ISR Boundary b Ringnes Bay Ellef Norwegian Coburg Island Grise Fiord a Ringnes Bay Island ARCTIC MARINE z Island EEZ Boundary Prince i Borden ARCTIC l Island Gustaf E Adolf Sea Maclea Jones n Str OCEAN n ait Sound ATLANTIC e Mackenzie Pe Ball nn antyn King Island y S e trait e S u trait it Devon Wel ATLAS Stra OCEAN Q Prince l Island Clyde River Queens in Bylot Patrick Hazen Byam gt Channel o Island Martin n Island Ch tr. Channel an Pond Inlet S Bathurst nel Qikiqtarjuaq liam A Island Eclipse ust Lancaster Sound in Cornwallis Sound Hecla Ch Fitzwil Island and an Griper nel ait Bay r Resolute t Melville Barrow Strait Arctic Bay S et P l Island r i Kel l n e c n e n Somerset Pangnirtung EEZ Boundary a R M'Clure Strait h Island e C g Baffin Island Brodeur y e r r n Peninsula t a P I Cumberland n Peel Sound l e Sound Viscount Stefansson t Melville Island Sound Prince Labrador of Wales Igloolik Prince Sea it Island Charles ra Hadley Bay Banks St s Island le a Island W Hall Beach f Beaufort o M'Clintock Gulf of Iqaluit e c n Frobisher Bay i Channel Resolution r Boothia Boothia Sea P Island Sachs Franklin Peninsula Committee Foxe Harbour Strait Bay Melville Peninsula Basin Kimmirut Taloyoak N UNAT Minto Inlet Victoria SIA VUT Makkovik Ulukhaktok Kugaaruk Foxe Island Hopedale Liverpool Amundsen Victoria King -

Regional Development Patterns in Canada

Regional Development Patterns in Canada David Andolfatto Simon Fraser University and Ying Yan Simon Fraser University Version: July 2008 1. INTRODUCTION We provide annual data over the sample period 1981-2007 for income and pop- ulation dynamics in Canada and her provinces. 2. POPULATION PATTERNS In 1981, Canada’s population stood at nearly 25 million people. Since then, it has grown at an average rate of just over 1% per annum. As of 2007, the country’s population is very close to 33 million people; see Figure 1. Figure 1 Canadian Population 34 32 30 Million 28 26 24 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 06 1 With the exception of Newfoundland, the populations of each province grew over the 1981-2007 sample period. However, as Table 1 reveals, the great majority of the increase in Canada’s population is accounted for by just three provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario. Table 1 Average Annual Population Growth Rate (1981-2007) BC AB SK MA ON QC NS NB NF PE 1.64 1.55 0.08 0.50 1.39 0.60 0.33 0.22 —0.47 0.42 Figures 2A and 2B plot population shares for Canada’s largest and small- est provinces, respectively. While Ontario and Quebec continue to be Canada’s largest provinces by population, the two provinces exhibit very different secular trends, with Ontario gaining share and Quebec steadily losing share. Both British Columbia and Alberta have increased their shares over the sample period. British Columbia, in particular, displays rapid population growth over the period 1991- 1996. -

NAFTA and the Geography of North American Trade

WORKING PAPER SERIES NAFTA and the Geography of North American Trade Howard J. Wall Working Paper 2000-017C http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2000/2000-017.pdf Revised July 2002 FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS Research Division 411 Locust Street St. Louis, MO 63102 ______________________________________________________________________________________ The views expressed are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the Federal Reserve System, or the Board of Governors. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. References in publications to Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Papers (other than an acknowledgment that the writer has had access to unpublished material) should be cleared with the author or authors. Photo courtesy of The Gateway Arch, St. Louis, MO. www.gatewayarch.com NAFTA and the Geography of North American Trade* Howard J. Wall† Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis April 2000, revised June 2002 Abstract Debates over the desirability a preferential trading area (PTA) begin with the supposition that it will have two effects on the volume of trade: it will increase trade between PTA members, and decrease trade between members and non-members. This paper demonstrates, however, that at the regional level the effects of NAFTA have been much more complicated than what is normally supposed should happen. Specifically, NAFTA has meant (i) less trade between Eastern Canada and the United States and Mexico, (ii) more trade between Central Canada and the United States and Mexico, and (iii) more trade between Western Canada and Mexico, but no change in the volume of trade between Western Canada and the United States. -

Regional, Seasonal, and Historic Arctic Temperature Change

1.12 REGIONAL, SEASONAL, AND HISTORIC ARCTIC TEMPERATURE CHANGE James E. Overland1*, Michael C. Spillane2, and Kevin R. Wood1 1NOAA/PMEL, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115 2JISAO, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 1. INTRODUCTION had warm temperatures and increased volcano influence. These authors use this result as an argument for the Recent studies show considerable change in the importance of the uniqueness of CO2 increases in Arctic over the previous three decades in both physical overcoming the volcanic deficit in the recent period. and biological indicators (Serreze et al. 2001; Overland et Thus we have two competing visions of the current al. 2003). These indicators suggest a shift in atmospheric situation at high northern latitudes. In this paper we parameters such as the Arctic Oscillation and related reexamine the historical climate observational record. We stratospheric cooling around 1989, while sub-Arctic focus on changes in each season and in different regions records such as permafrost records show more gradual of the Arctic, rather than developing an additional trends. It is obviously important to put these recent contribution to annual zonal averages. Although data changes into historical context. coverage is far from complete, we consider it important to Two recent studies call into question major changes make the best use of existing information. With recent in the recent period based on longitudinally and annually understanding of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and averaged temperature data. Przybylak (2000) states Arctic Oscillation (AO) dynamics and their relation to “contemporary global warming in the Arctic is either very stratospheric cooling in winter and spring, we can develop weakly marked or even not seen at all.” Polyakov et al. -

REPORT No. 37 IGBP Northern Eurasia Study

REPORT No. 37 IGBP Northern Eurasia Study: Prospectus for an Integrated Global Change Research Project The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme: A Study of Global Change (IGBP) of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) Stockholm, 1996 ----------~----.-~~~---- GLoBAL CHANGE REPORT No. 37 IGBP Northern Eurasia Study: Prospectus for an Integrated Global Change Research Project Edited by W.L. Steffen and A.Z. Shvidenko With contributions from H. Bugmann, F.S. Chapin Ill, J.G. Goldammer, S. Hahn, R. Harding, P. Hogberg, G. Inoue, P.G. Jarvis, P. Kabat, A. Krenke, P. Kuhry, H. Lee, J.S. Levine, S. Linder, S. Nilsson, T. Ohata, A. Pszenny, W.S. Reeburgh, R. Rosenberg, E.-D. Schulze and K.A. Smith The International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme: A Study of Global Change (IGBP) of the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) Stockholm, 1996 The international planning and coordination of the IGBP is supported by IGBP National Committees, the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), the European Contents Commission, the National Science Foundation (USA), The Federal Ministry for Education, Science, Research and Technology (BMBF, Germany), Deutscbe Forschungsgemeinscbaft (DFG, Germany), Governments and industry. This report is also available in Russian. Executive Summary 5 Preface 9 Background 10 Goals of the Study 17 General Biogeography of Northern Eurasia 19 General Organisation of the Study 22 Design of the Transect Component 24 Design of the Network Component 29 Design of the Water, Energy and Carbon Flux Component 31 Design of the Fire Component 34 Modelling, Integration and Data 35 Global Change Impacts on Managed Forests 41 Interactions 42 Resource Requirements and Priorities 46 Next Steps 47 References 50 Glossary 54 Appendix 1: Site Characterisation: Required Data on Vegetation, Soil, Land Use and Climate for Trace Gas Flux Measurements. -

Going in Reverse: the Tar Sands Oil Threat to Central Canada and New England

© David Dodge, The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society © Stephen Demetriou TAR SANDS FACTS By June 2009, tar sands mining The Portland-Montreal pipeline flows underground beneath dozens of operations had destroyed an area of communities throughout New England and Central Canada. the Boreal forest that was one and a half times the size of Denver, Colorado. Going in Reverse: The Tar Sands Oil Threat to Central Canada and New England The oil industry is pursuing a plan to transport tar sands oil through some of the most important natural and cultural landscapes in Central Canada, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Under the plan, Enbridge’s Line 9 and ExxonMobil’s Portland-Montreal pipeline would be reversed to send Canadian tar sands oil—some of the dirtiest oil on the planet—along an approximately 750-mile (1200 km) route. The pipeline would run east through Ontario and Quebec, and down to the New England seacoast, finally ending in Portland, Maine’s Casco Bay from where tar sands oil could be sent anywhere in the world for refining. Enbridge has taken steps to implement this plan by filing permit applications with Canada’s National Energy Board to reverse the flow of the pipeline and expand Line 9. Meanwhile, Portland-Montreal pipeline officials have been actively lobbying local government officials in New England to promote tar sands. But communities in New England, Ontario, and Quebec are fighting this risky tar sands pipeline and supporting clean energy solutions. The removal of tar sands oil from the ground is a destructive England do not need to bear the risks of tar sands pipelines so business.