The Distribution of Permafrost and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada GREENLAND 80°W

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-B Module 7 70°N 30°W 20°W 170°W 180° 70°N 160°W Canada GREENLAND 80°W 90°W 150°W 100°W (DENMARK) 120°W 140°W 110°W 60°W 130°W 70°W ARCTIC Essential Question OCEANDo Canada’s many regional differences strengthen or weaken the country? Alaska Baffin 160°W (UNITED STATES) Bay ic ct r le Y A c ir u C k o National capital n M R a 60°N Provincial capital . c k e Other cities n 150°W z 0 200 400 Miles i Iqaluit 60°N e 50°N R YUKON . 0 200 400 Kilometers Labrador Projection: Lambert Azimuthal TERRITORY NUNAVUT Equal-Area NORTHWEST Sea Whitehorse TERRITORIES Yellowknife NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Hudson N A Bay ATLANTIC 140°W W E St. John’s OCEAN 40°W BRITISH H C 40°N COLUMBIA T QUEBEC HMH Middle School World Geography A MANITOBA 50°N ALBERTA K MS_SNLESE668737_059M_K.ai . S PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND R Edmonton A r Canada legend n N e a S chew E s kat Lake a as . Charlottetown r S R Winnipeg F Color Alts Vancouver Calgary ONTARIO Fredericton W S Island NOVA SCOTIA 50°WFirst proof: 3/20/17 Regina Halifax Vancouver Quebec . R 2nd proof: 4/6/17 e c Final: 4/12/17 Victoria Winnipeg Montreal n 130°W e NEW BRUNSWICK Lake r w Huron a Ottawa L PACIFIC . t S OCEAN Lake 60°W Superior Toronto Lake Lake Ontario UNITED STATES Lake Michigan Windsor 100°W Erie 90°W 40°N 80°W 70°W 120°W 110°W In this module, you will learn about Canada, our neighbor to the north, Explore ONLINE! including its history, diverse culture, and natural beauty and resources. -

Assessing Snow Phenology Over the Large Part of Eurasia Using Satellite Observations from 2000 to 2016

remote sensing Article Assessing Snow Phenology over the Large Part of Eurasia Using Satellite Observations from 2000 to 2016 Yanhua Sun 1, Tingjun Zhang 1,2,*, Yijing Liu 1, Wenyu Zhao 1 and Xiaodong Huang 3 1 Key Laboratory of West China’s Environment (DOE), College of Earth and Environment Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China; [email protected] (Y.S.); [email protected] (Y.L.); [email protected] (W.Z.) 2 University Corporation for Polar Research, Beijing 100875, China 3 School of Geographical Sciences, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-138-9337-2955 Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 23 June 2020; Published: 26 June 2020 Abstract: Snow plays an important role in meteorological, hydrological and ecological processes, and snow phenology variation is critical for improved understanding of climate feedback on snow cover. The main purpose of the study is to explore spatial-temporal changes and variabilities of the extent, timing and duration, as well as phenology of seasonal snow cover across the large part of Eurasia from 2000 through 2016 using a Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud-free snow product produced in this study. The results indicate that there are no significant positive or negative interannual trends of snow cover extent (SCE) from 2000 to 2016, but there are large seasonal differences. SCE shows a significant negative trend in spring (p = 0.01) and a positive trend in winter. The stable snow cover areas accounting for 78.8% of the large part of Eurasia, are mainly located north of latitude 45◦ N and in the mountainous areas. -

Determining Carbon Stocks in Cryosols Using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database

Permafrost, Phillips, Springman & Arenson (eds) © 2003 Swets & Zeitlinger, Lisse, ISBN 90 5809 582 7 Determining carbon stocks in Cryosols using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database C. Tarnocai Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada J. Kimble USDA-NRCS-NSSC, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA G. Broll Institute of Landscape Ecology, University of Muenster, Muenster, Germany ABSTRACT: The distribution of Cryosols and their carbon content and mass in the northern circumpolar area were estimated by using the Northern and Mid Latitudes Soil Database (NMLSD). Using this database, it was estimated that, in the Northern Hemisphere, Cryosols cover approximately 7769 ϫ 103 km2 and contain approxi- mately 119 Gt (surface, 0–30 cm) and 268 Gt (total, 0–100 cm) of soil organic carbon. The 268 Gt organic carbon is approximately 16% of the world’s soil organic carbon. Organic Cryosols were found to have the highest soil organic carbon mass at both depth ranges while Static Cryosols had the lowest. The accuracy of these carbon val- ues is variable and depends on the information available for the area. Since these soils contain a significant por- tion of the Earth’s soil organic carbon and will probably be the soils most affected by climate warming, new data is required so that more accurate estimates of their carbon budget can be made. 1 INTRODUCTION which is in Arc/Info format, the Soils of Northern and Mid Latitudes (Tarnocai et al. 2002a) and Northern Soils are the largest source of organic carbon in ter- Circumpolar Soils (Tarnocai et al. 2002b) maps were restrial ecosystems. -

Frequency and Characteristics of Arctic Tundra Fires

Frequency and Characteristics of Arctic Tundra Fires ABSTRACT. Characteristics of over 50 tundra fires, located primarily in the west- em Arctic, are summarized. In general, only recent records were available and the numbers of fires were closely related to the accessibility of the area. Most of them covered areas of less than one square kilometre (in contrast to forest fires which are frequently larger) but three tundra fires on the Seward Peninsula of Alaska burned, in aggregate, 16,000 square kilometres of cottongrass tussocks. Though tundra fires can occur as early as May, most of them break out in July and early August. Biomass decreases,and so fires are more easily stopped by discontinuities in vegetation, with distance northward. &UM&. Friquence et curacttWstiques des incendies de toundra de l'Arctique. L'auteur rbume les caractiristiques de 50 incendies de toundra ayant eu lieu princi- palement dans l'Arctique de l'ouest. Eh g6nnk.al il disposait seulement d'une docu- mentation rhnte et le nombre des incendies &ait 6troitementlit$ B PaccessibilitC de la r6gion. La plupart des incendies couvrait des surfaces inf6rieures A un kilombtre carré (en contraste avec les incendiesde fori%), mais une totalit6 de 1600 kilom&tres cm&de tussach de linaigrette brQlhrent au cours de trois incendie? sur la phinsulc de Seward en Alaska. Même si d6jB en mai des incendies de toundra peuvent s'allu- mer, la plupart ont lieu en juillet et au d6but d'aoQt. Au fur et B mesure que l'on monte vers le Nord la quantit6 de vbg6tation (CA"de combustible) diminue et les incendies sont ainsi plus facilement arrêtb par lesintervalles qui sbarent les surfaces couvertes de vhgétation. -

Ancient Fennoscandian Genomes Reveal Origin and Spread of Siberian Ancestry in Europe

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5 OPEN Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe Thiseas C. Lamnidis1, Kerttu Majander1,2,3, Choongwon Jeong1,4, Elina Salmela 1,3, Anna Wessman5, Vyacheslav Moiseyev6, Valery Khartanovich6, Oleg Balanovsky7,8,9, Matthias Ongyerth10, Antje Weihmann10, Antti Sajantila11, Janet Kelso 10, Svante Pääbo10, Päivi Onkamo3,12, Wolfgang Haak1, Johannes Krause 1 & Stephan Schiffels 1 1234567890():,; European population history has been shaped by migrations of people, and their subsequent admixture. Recently, ancient DNA has brought new insights into European migration events linked to the advent of agriculture, and possibly to the spread of Indo-European languages. However, little is known about the ancient population history of north-eastern Europe, in particular about populations speaking Uralic languages, such as Finns and Saami. Here we analyse ancient genomic data from 11 individuals from Finland and north-western Russia. We show that the genetic makeup of northern Europe was shaped by migrations from Siberia that began at least 3500 years ago. This Siberian ancestry was subsequently admixed into many modern populations in the region, particularly into populations speaking Uralic languages today. Additionally, we show that ancestors of modern Saami inhabited a larger territory during the Iron Age, which adds to the historical and linguistic information about the population history of Finland. 1 Department of Archaeogenetics, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, 07745 Jena, Germany. 2 Institute for Archaeological Sciences, Archaeo- and Palaeogenetics, University of Tübingen, 72070 Tübingen, Germany. 3 Department of Biosciences, University of Helsinki, PL 56 (Viikinkaari 9), 00014 Helsinki, Finland. -

The Different Stratospheric Influence on Cold-Extremes in Eurasia and North America

The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Kretschmer, M. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2756- 9526, Cohen, J., Matthias, V., Runge, J. and Coumou, D. (2018) The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America. npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 1 (1). ISSN 2397-3722 doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/92433/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41612-018-0054-4 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online www.nature.com/npjclimatsci ARTICLE OPEN The different stratospheric influence on cold-extremes in Eurasia and North America Marlene Kretschmer1,2, Judah Cohen3, Vivien Matthias1, Jakob Runge4 and Dim Coumou1,5 The stratospheric polar vortex can influence the tropospheric circulation and thereby winter weather in the mid-latitudes. Weak vortex states, often associated with sudden stratospheric warmings (SSW), have been shown to increase the risk of cold-spells especially over Eurasia, but its role for North American winters is less clear. -

Evolution of Winter Temperature in Toronto, Ontario, Canada: a Case Study of Winters 2013/14 and 2014/15

15 JULY 2017 A N D E R S O N A N D GOUGH 5361 Evolution of Winter Temperature in Toronto, Ontario, Canada: A Case Study of Winters 2013/14 and 2014/15 CONOR I. ANDERSON AND WILLIAM A. GOUGH Department of Physical and Environmental Sciences, University of Toronto Scarborough, Scarborough, Ontario, Canada (Manuscript received 29 July 2016, in final form 27 March 2017) ABSTRACT Globally, 2014 and 2015 were the two warmest years on record. At odds with these global records, eastern Canada experienced pronounced annual cold anomalies in both 2014 and 2015, especially during the 2013/14 and 2014/15 winters. This study sought to contextualize these cold winters within a larger climate context in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Toronto winter temperatures (maximum Tmax, minimum Tmin,andmeanTmean)for the 2013/14 and 2014/15 seasons were ranked among all winters for three periods: 1840/41–2015 (175 winters), 1955/56–2015 (60 winters), and 1985/86–2015 (30 winters), and the average warming trend for each temperature metric during these three periods was analyzed using the Mann–Kendall test and Thiel–Sen slope estimation. The winters of 2013/14 and 2014/15 were the 34th and 36th coldest winters in Toronto since record-keeping began in 1840; however these events are much rarer, relatively, over shorter periods of history. Overall, Toronto winter temperatures have warmed considerably since winter 1840/41. The Mann–Kendall analysis showed statistically significant monotonic trends in winter Tmax, Tmin,andTmean over the last 175 and 60 years. These trends notwithstanding, there has been no clear signal in Toronto winter temperature since 1985/86. -

Vegetation and Lake Changes on the Southern Taymyr Peninsula, Northern Siberia, During the Last 300 Years Inferred from Pollen and Pediastrum Green Algae Records

Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät Bastian Niemeyer | Ulrike Herzschuh | Luidmila Pestryakova Vegetation and lake changes on the southern Taymyr peninsula, northern Siberia, during the last 300 years inferred from pollen and Pediastrum green algae records Suggested citation referring to the original publication: The Holocene 25(4) (2015) DOI https://doi.org/10.1177/0959683614565954 ISSN (print) 0959-6836 ISSN (online) 1477-0911 Postprint archived at the Institutional Repository of the Potsdam University in: Postprints der Universität Potsdam Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Reihe ; 421 ISSN 1866-8372 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-404880 HOL0010.1177/0959683614565954The HoloceneNiemeyer et al. 565954research-article2015 Research paper The Holocene 2015, Vol. 25(4) 596 –606 Vegetation and lake changes on the © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav southern Taymyr peninsula, northern DOI: 10.1177/0959683614565954 Siberia, during the last 300 years inferred hol.sagepub.com from pollen and Pediastrum green algae records Bastian Niemeyer,1 Ulrike Herzschuh1,2 and Luidmila Pestryakova3 Abstract Siberian arctic vegetation and lake water communities, known for their temperature dependence, are expected to be particularly impacted by recent climate change and high warming rates. However, decadal information on the nature and strength of recent vegetation change and its time lag to climate signals are rare. In this study, we present a 210Pb/137Cs dated pollen and Pediastrum species record from a unnamed lake in the south of the Taymyr peninsula covering the period from AD 1706 to 2011. Thirty-nine palynomorphs and 10 morphotypes of Pediastrum species were studied to assess changes in vegetation and lake conditions as probable responses to climate change. -

A Polar System of Intercontinental Bird Migration Thomas Alerstam1,*, Johan Ba¨Ckman1, Gudmundur A

Proc. R. Soc. B (2007) 274, 2523–2530 doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0633 Published online 7 August 2007 A polar system of intercontinental bird migration Thomas Alerstam1,*, Johan Ba¨ckman1, Gudmundur A. Gudmundsson2, Anders Hedenstro¨m3, Sara S. Henningsson1,Ha˚kan Karlsson1, Mikael Rose´n1 and Roine Strandberg1 1Department of Animal Ecology, and 3Department of Theoretical Ecology, Lund University, Ecology Building, 223 62 Lund, Sweden 2Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Hlemmur 3, PO Box 5320, 125 Reykjavik, Iceland Studies of bird migration in the Beringia region of Alaska and eastern Siberia are of special interest for revealing the importance of bird migration between Eurasia and North America, for evaluating orientation principles used by the birds at polar latitudes and for understanding the evolutionary implications of intercontinental migratory connectivity among birds as well as their parasites. We used tracking radar placed onboard the ice-breaker Oden to register bird migratory flights from 30 July to 19 August 2005 and we encountered extensive bird migration in the whole Beringia range from latitude 648 N in Bering Strait up to latitude 758 N far north of Wrangel Island, with eastward flights making up 79% of all track directions. The results from Beringia were used in combination with radar studies from the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia and in the Beaufort Sea to make a reconstruction of a major Siberian–American bird migration system in a wide Arctic sector between longitudes 1108 Eand1308 W, spanning one-third of the entire circumpolar circle. This system was estimated to involve more than 2 million birds, mainly shorebirds, terns and skuas, flying across the Arctic Ocean at mean altitudes exceeding 1 km (maximum altitudes 3–5 km). -

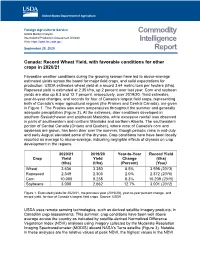

Canada: Record Wheat Yield, with Favorable Conditions for Other Crops in 2020/21

Foreign Agricultural Service Global Market Analysis Commodity International Production Assessment Division Web: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov Intelligence September 29, 2020 Report Canada: Record Wheat Yield, with favorable conditions for other crops in 2020/21 Favorable weather conditions during the growing season have led to above-average estimated yields across the board for major field crops, and solid expectations for production. USDA estimates wheat yield at a record 3.64 metric tons per hectare (t/ha). Rapeseed yield is estimated at 2.35 t/ha, up 2 percent over last year. Corn and soybean yields are also up 8.3 and 12.7 percent, respectively, over 2019/20. Yield estimates, year-to-year changes, and records for four of Canada’s largest field crops, representing both of Canada’s major agricultural regions (the Prairies and Central Canada), are given in Figure 1. The Prairies saw warm temperatures throughout the summer and generally adequate precipitation (Figure 2). At the extremes, drier conditions developed in southern Saskatchewan and southeast Manitoba, while excessive rainfall was observed in parts of southwestern and northern Manitoba and northern Alberta. The southeastern portion of Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec), where most of Canada's corn and soybeans are grown, has been drier over the summer, though periodic rains in mid-July and early August aleviated some of the dryness. Crop conditions here have been locally reported as average to above-average, indicating negligible effects of dryness on crop development in the regions. 2020/21 2019/20 Year-to-Year Record Yield Crop Yield Yield Change (t/ha) (t/ha) (t/ha) (Percent) (Year) Wheat 3.636 3.350 8.5% 3.598 (2013) Rapeseed 2.349 2.303 2.0% 2.372 (2016) Corn 10.000 9.238 8.3% 10.209 (2015) Soybeans 3.000 2.662 12.7% 3.001 (2012) Figure 1. -

TEACHER NOTES 6TH GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Latin America and Canada - HISTORICAL UNDERSTANDINGS - SS6H1 - Explain Conflict and Change in Latin America

6th Grade Social Studies Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies The Teacher Notes were developed to help teachers understand the depth and breadth of the standards. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Please remember that the goal of Social Studies is not to have students memorize laundry lists of facts, but rather to help them understand the world around them so they can analyze issues, solve problems, think critically, and become informed citizens. Children’s Literature: A list of book titles aligned to the 6th-12th Grade Social Studies GSE may be found at the Georgia Council for the Social Studies website: http://www.gcss.net/uploads/files/Childrens-Literature-Grades-6-to-12.pdf TEACHER NOTES 6TH GRADE SOCIAL STUDIES Latin America and Canada - HISTORICAL UNDERSTANDINGS - SS6H1 - Explain conflict and change in Latin America. Standard H1 explores the contemporary events of Latin American history which have shaped the current geopolitical and socioeconomic climate of the region. As with all 6th grade historical standards, it is not intended to serve as an exhaustive history of the region, but rather a snapshot of major events and historical trends that help explain the current state of Latin American affairs. In this regard, special attention is given to the transformative influence of Spanish and Portuguese exploration and colonization in the region, the cultural and economic impact of the transatlantic slave trade, the geopolitical impact of Cuba’s 1959 communist revolution, and the status of U.S. -

Mountain-Derived Versus Shelf-Based Glaciations on the Western Taymyr Peninsula, Siberia Christian Hjort1 & Svend Funder2

Mountain-derived versus shelf-based glaciations on the western Taymyr Peninsula, Siberia Christian Hjort1 & Svend Funder2 1 Quaternary Sciences, Lund University, GeoCenter II, Sölvegatan 12, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden 2 Natural History Museum, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5-7, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Keywords Abstract Siberian geology; glacial inception; glacial history. The early Russian researchers working in central Siberia seem to have preferred scenarios in which glaciations, in accordance with the classical gla- Correspondence ciological concept, originated in the mountains. However, during the last 30 C. Hjort, Quaternary Sciences, Lund years or so the interest in the glacial history of the region has concentrated on University, GeoCenter II, Sölvegatan 12, ice sheets spreading from the Kara Sea shelf. There, they could have originated SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden. E-mail: from ice caps formed on areas that, for eustatic reasons, became dry land [email protected] during global glacial maximum periods, or from grounded ice shelves. Such ice doi:10.1111/j.1751-8369.2008.00068.x sheets have been shown to repeatedly inundate much of the Taymyr Peninsula from the north-west. However, work on westernmost Taymyr has now also documented glaciations coming from inland. On at least two occasions, with the latest one dated to the Saale glaciation (marine isotope stage 6 [MIS 6]), warm-based, bedrock-sculpturing glaciers originating in the Byrranga Moun- tains, and in the hills west of the range, expanded westwards, and at least once did such glaciers, after moving 50–60 km or more over the present land areas, cross today’s Kara Sea coastline.