Information Note on the Court's Case-Law 217 (April 2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

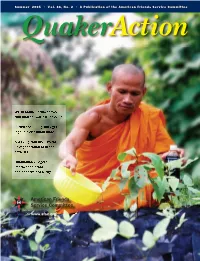

QUACTION Summer 05.Indd

Summer 2005 • V ol. 86, No. 2 • A Publication of the American Friends Service Committee QuakerAction World Social Forum shows that another world IS possible In Newark, immigrants get legal aid and much more Speaking tour inspires the next generation of Africa activists Cambodian villagers improve their food and economic security www.afsc.org What’s new Summer 2005 on afsc.org QuakerAction V ol. 86, No. 2 Join our email newsletter FEATURES We’ve recently reformatted our monthly email newsletter to better inform you about our current 3 Imagine actions and resources. World Social Forum shows that another www.afsc.org/email/ world IS possible Find Youth and Militarism resources 4 A family feeling Find information In Newark, immigrants get legal aid and about what’s much more true and false in military recruit- Foss Terry ing, conscien- 7 Putting all the options on the table tious objection, P A G E S I X AFSC ????? AFSC and military recruitment the military’s access to our schools, and more. www.afsc.org/youthmil/ DEPARTMENTS Support Israeli conscientious objectors 8 Currents AFSC’s Faces of Hope campaign has information about jailed Israeli News from around AFSC conscientious objectors and ways you can help support them. 10 Words from Our Sponsors www.afsc.org/israel-palestine A China workcamp volunteer All about economic justice continues a family tradition Terry Foss Terry From one page, you can now fi nd resources, action alerts, and more PAGEP A G E ELEVENE L E V E N 11 Focus on Missouri about our federal budget priorities, Speaking tour inspires the next international debt, maquiladoras, trade pacts, and other economic generation of Africa activists justice issues. -

Visions of Vietnam

DATA BOOK STAKES RESULTS European Pattern 2008 : HELLEBORINE (f Observatory) 3 wins at 2, wins in USA, Mariah’s Storm S, 2nd Gardenia H G3 . 277 PARK HILL S G2 Prix d’Aumale G3 , Prix Six Perfections LR . 280 DONCASTER CUP G2 Dam of 2 winners : 2010 : (f Observatory) 2005 : CONCHITA (f Cozzene) Winner at 3 in USA. DONCASTER. Sep 9. 3yo+f&m. 14f 132yds. DONCASTER. September 10. 3yo+. 18f. 2006 : Towanda (f Dynaformer) 1. EASTERN ARIA (UAE) 4 9-4 £56,770 2nd Dam : MUSICANTI by Nijinsky. 1 win in France. 1. SAMUEL (GB) 6 9-1 £56,770 2008 : WHITE MOONSTONE (f Dynaformer) 4 wins b f by Halling - Badraan (Danzig) Dam of DISTANT MUSIC (c Distant View: Dewhurst ch g by Sakhee - Dolores (Danehill) at 2, Meon Valley Stud Fillies’ Mile S G1 , O- Sheikh Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum S G1 , 3rd Champion S G1 ), New Orchid (see above) O/B- Normandie Stud Ltd TR- JHM Gosden Keepmoat May Hill S G2 , germantb.com Sweet B- Darley TR- M Johnston 2. Tastahil (IRE) 6 9-1 £21,520 Solera S G3 . 2. Rumoush (USA) 3 8-6 £21,520 Broodmare Sire : QUEST FOR FAME . Sire of the ch g by Singspiel - Luana (Shaadi) 2009 : (f Arch) b f by Rahy - Sarayir (Mr Prospector) dams of 24 Stakes winners. In 2010 - SKILLED O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Darley TR- BW Hills 2010 : (f Tiznow) O- Hamdan Al Maktoum B- Shadwell Farm LLC Commands G1, TAVISTOCK Montjeu G1, SILVER 3. Motrice (GB) 3 7-12 £10,770 TR- MP Tregoning POND Act One G2, FAMOUS NAME Dansili G3, gr f by Motivator - Entente Cordiale (Affirmed) 2nd Dam : DESERT STORMETTE by Storm Cat. -

Iquitos Leads Sunday Double for Adlerflug

MONDAY, 5 SEPTEMBER, 2016 IQUITOS LEADS SUNDAY YANKEE HEADED TO GOLDEN ROSE DOUBLE FOR ADLERFLUG G1 Sires= Produce S. winner Yankee Rose (Aus) (All American {Aus}) was given the go-ahead by trainer David Vandyke for Saturday=s G1 Golden Rose S. after a satisfactory work between races at the Sunshine Coast on Sunday. The 3-year-old filly has not had a straightforward start to her prep, but Vandyke told Sky Thoroughbred Central he was pleased with Sunday=s work. "She had a good blow and her heart rate was up but her recovery was good," Vandyke said. "She is a frustrating filly to train. She doesn't do a lot in training or trials and she had a joint issue a couple of weeks ago. I put the blinkers on and we saw an improved horse.@ "She was committed to the cause and really worked to the line strongly,@ he added. "Bringing her to the races and putting the blinkers on has done the trick." Iquitos takes the Longines Grosser Preis von Baden | Marc Ruhl IN TDN AMERICA TODAY LUCY AND ETHEL CAUSES PRIORESS BOILOVER Iquitos (Ger) (Adlerflug {Ger}) first emerged on the major First-up since running her record to three-from-three in the GIII domestic scene when runner-up to the G1 Deutsches Derby Old Hat S. in January, Lucy and Ethel (During) fought out the second Palace Prince (Ger) (Areion {Ger}) in the 10-furlong pace to register a 22-1 upset of a strong field in the GII Prioress S. G3 Grosser Preis der Sparkasse Krefeld last August, but was not at Saratoga. -

STORM CAT RECORD SIX TIME (859) 273-1514 P Fax (859) 273-0034 Leading Sire of 2Yos TDN P HEADLINE NEWS • 8/9/04 • PAGE 2 of 8

2007 Breeders’ Cup set for Monmouth HEADLINE p. 1 (atw) NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND FREE BY E-M AIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF call 732-747-8060. www.thoroughbreddailynews.com MONDAY, AUGUST 9, 2004 LION HEART REIGNS IN HASKELL PURGE ROCKETS TO JIM DANDY VICTORY Seven years ago, a lightly raced colt by the name of Following an inexplicably poor showing in his latest Tale of the Cat finished a respectable fourth in the GI start in the GI Belmont S. June 5, Purge (Pulpit) re- Haskell Invitational. Yesterday his son, Lion Heart, came turned to his winning ways with an impressive 4 1/2- back to avenge his sire’s loss with a one-length tally in length score in Sunday’s GII Jim Dandy S. at Saratoga this year’s renewal of the Monmouth centerpiece. De- Race Course. Close-up to pacesetter Medallist (Touch spite a win over the track last time out in the GIII Long Gold), who was coming into this Branch Breeders’ Cup H. July race fresh off a stake record-set- 17, Lion Heart was made the ting performance in the GII second choice in the betting this Dwyer S. July 11, Purge forced time around, with GII Swaps S. the issue early, but allowed that winner Hard Rock Ten (Kris S.) rival to steal away from him after getting backed down to 4-5 fa- three quarters of a mile in 1:09.64. voritism. In command from the Closing quickly turning for home, Purge Horsephotos start, Lion Heart broke alertly Purge passed Medallist with Lion Heart Equi-photo and was allowed to carve out a consumate ease, drew clear of his foe in the final fur- sensible opening quarter in :23 long and remained in front late to post a facile win. -

1C5 DAILY NEWS" October 3, 1999 Ft INTERNATIONAL Ft

; The-TDN is delivered each morning by 5 a.m. Eastern. For subscription information, please call (732) 747-8060. • THOROUGHBRED Sunday, 1C5 DAILY NEWS" October 3, 1999 ft INTERNATIONAL ft CLASH OF THE TITANS AT LONGCHAMP Today, Longchamp, France, post time: 3:50 p.m. It just seems like it has been raining in Paris for 40 days PRIX DE L'ARC DE TRIOMPHE-LUCIEN BARRIERE-G1, and nights, so punters should not confuse today's FF8,750,000, 3yo/up, c/f, 1 1/2mT Longchamp feature for an "arc" of a different variety. sc (PP) HORSE TRAINER JOCKEY ODDS Despite the sticky conditions, Europe's two dominant 1 (10) Daylami (Ire) bin Suroor Dettori 9-4 middle-distance horses are set lock horns this afternoon h, 5, Doyoun (Irej-Daltawa (Ire), by Miswaki in Paris. IViontjeu only just got up to win the G2 Prix 2 (14) Croco Rouge (Ire) Bary Jarnet 10-1 Niel at Longchamp Sept. 12, albeit after a mid-season break, and had previously displayed his star quality c, 4, Rainbow Quest--Alligatrix, by Alleged when scoring in both the French and Irish Derbies at 3 (12) Albaran (Ger) Erichsen Tandori 200-1 Chantiliy June 6 and The Curragh June 27 respectively. h, 6, Sure Blade-Araqueen (Ger), byKonigsstuhl(Ger) If all goes according to plan, he will be hard to beat. 4 (6) Tiger Hill (Ire) Schiergen Hellier 11-1 Daylami, proven at this standard, bids to seize the the c, 4, Danehill-The Filly (Ger), by Appiani if (Ity) champion middle distance crown from Montjeu's grasp 5 (1) El Condor Pasa Ninomiya Ebina 6-1 and will do so if complementing his Group 1 wins in the c, 4, Kingmambo-Saddlers Gal (Ire), bySadler's Wells Coronation Cup at Epsom June 4, the King George V! & 6 (5) Greek Dance (Ire) Stoute Fallon 12-1 Queen Elizabeth Diamond S. -

W-2 O Me View Bee Lined by Ad Hoc Commiffee

BSU Backers Plan Meeting Today budget? or regulation that would encourage "Priorities do change, and available all haveTecords of d i s t i n g u i s h c (1 complete and detailed By MARGE COHEN other to prepare for the public hearings "The University President presents of the State-House Higher Education Sub- racism. funds arc often reallocated on the basis academic service. Their records speal. Collegian Feature Editor will The of changing priorities. However, it must for themselves. the budget before committees of the committee scheduled -. for Dec. 4 and 5 at "What definite commitment year. The University make to eradicate , racism? be made clear that funds from the "In what way is The Univor sit> House and Senate each . University President Eric A. Walker University Park. University publishes a complete iinait-ial yesterday issued a .statement thai "the ' "See the sta tements above. federal and slate governments earmark- fulfilling the mandate of its Land Grant The text of the group s questions and recognize the ed for specific uses cannot be diverted to Charter? report, known as the Controller 's Report, University does not have a rule or Walker 's answers follows. "Docs the University at Pattee regulation that would encourage racism." BSU as the spokesman of the black com- alternate uses. Nor can funds from "The University issues r c g u I a r annually. It is available "Does racism exist at The Legislature and the Com- Library. ¦Walker ' munity of Penn State? private sources, given for specific uses reports to Ihe s statement came in response University ? recent con- be used for other purposes." monwealth on the ways it is fulfilling the "Docs the University realize the to a list of 10 questions on racism within "On the basis of it con- "One can define racism as a system versations, it is my understanding that What evidence exists in the creden- laiulgranl mandate. -

Lehmann?S As Reconstructed Fleuss, the Diver, Is the Present Sensation at Program of the Last Beethoven Rangementof The

THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE: SUNDAY, MAY 23, 1880?SIXTEEN PAGES. 11 months, though « failed to attract the people, notwithstandingthe she won?t sayto whom, and real- Grade Sterra and Hiss Adele Gelaer, two tal- collector darlngr some tea years of assiduous THE FAIR.? fine Belinda of Mrs. Agnes Booth. ly means to retire from the stage. She will MUSIC. ented young: ladles. The vocal talent comprises labor spent in gathering together Illustrations STAGE. ** spend THE ? the summer in Switzerland, play a while Mrs. S. C. Ford, Mrs. Jessie Bartlett Davis, two, ofShakspearelan subjects. At the National Theatrethis week Bosedale at theLondon Haymorkot will B. Warwick will per- in the fall, and then ladies deservedly popular; Miss Somers, Mr. be seen. Mr. Louis make a farewell tour of the British provinces. Knorr, Mr. McWado, ar- sonate Elliot Gray. and Mr. Noble. The Lehmann?s as Reconstructed Fleuss, the diver, is the present sensation at Program of the Last Beethoven rangementof the. haH is excellent In every- BO3IANOEFS. ?Twelfth Night,? A company known as the Marshall comedy the London Aquarium. It is said that he has in- respect, and the program announced for four city. It will most Webb. troupe has been organized in this vented some contrivance which dispenses with , Society Concert. concerts attractive. The Legitimacy of the Russian Impe- by Mr. Charles appear at Janesville, Wls., to-morrow. the usual pumping by ?PINAFORE? REDIVXVCa. FAIR. apparatus, and which be Family. Barnum, Nip cun water for a space of five ? rial George W. latelywith ?Tho ana remain under The everlasting ?Pinafore has been for some Pall Mall Gazette, Tuck? company, will manage the People?s The- hours. -

HEADLINE NEWS • 10/20/06 • PAGE 2 of 4

Badge of Silver Heads to BC Mile HEADLINE p.3 NEWS For information about TDN, DELIVERED EACH NIGHT BY FAX AND call 732-747-8060. FREE BY E-MAIL TO SUBSCRIBERS OF www.thoroughbreddailynews.com FRIDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2006 GEORGE HEADS COOLMORE ADDITIONS ARAGORN TO LANE’S END IN ‘07 Four new stud prospects will be added to Coolmore=s Multiple Grade I winner Aragorn (Ire) (Giant=s stallion team when George Washington (Ire) (DanehillB- Causeway--Onaga, by Mr. Prospector) will enter stud in Bordighera, by Alysheba), Hurricane Run (Ire) (Montjeu 2007 at William S. Farish=s Lane=s End Farm near Ver- {Ire}--Hold On {Ger}, by Surumu {Ger}), Aussie Rules sailles, Kentucky. Bred and raced by (DanehillB-Last Second {Ire}, by Belinda and Roy Strudwick=s Ballygallon Alzao) and Ad Valorem (Danzig- Stud, Aragorn will take a four-race win Classy Women, by Relaunch) streak into his final start in the GI Breed- retire following their final out- ers= Cup Mile Nov. 4 at Churchill Downs. ings on Breeders= Cup day at Winner of last year=s GII Oak Tree Derby, Churchill Downs Nov. 4. AThese the four-year-old began 2006 with are four seriously well-bred runner-up efforts in the GI Frank E Kilroe horses, by the right sires, from Mile H. and in the GII San Francisco top-class families and all have Aragorn Benoit Breeders= Cup S. He=s been unbeaten since, taking the May 29 GI Shoemaker Hurricane Run Horsephotos excelled at the very highest level on the racecourse,@ said Breeders= Cup Mile S., July 23 GI Eddie Read H., Aug. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

Irish Setter PRA Rcd1 Clear Results

Health - DNA Test Report: DNA - PRA (rcd1) Gundog - Irish Setter Dog Name Reg No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Test Result ACEOFACES DAWN RED WOOD AL00404004 23/11/2009 Bitch TREDURA BEHIND THE MASK REDGIRL'S PRINCESS 15/02/2011 Clear ACEOFACES EVIE STAR LIGHT AL00404002 23/11/2009 Bitch TREDURA BEHIND THE MASK REDGIRL'S PRINCESS 10/07/2015 Clear AMBERAE ARCHIMEDES T1143801T03 17/06/1993 Dog REDDINS FERDINAND FEARNLEY FIRESPRAY OF AMBERAE 17/01/1995 Clear AMBERAE AUTOMATIC R1822101R02 22/02/1991 Dog REDDINS NIALL FEARNLEY FIRESPRAY OF AMBERAE 05/10/1996 Clear AMBERWAVE FRECKLES AG04832801 08/10/2006 Bitch THENDARA DON CORLEONE AMBERWAVE SPANGLE 22/03/2013 Clear AMBERWAVE HEAVENLY SECRET R0581407R01 13/11/1990 Bitch CLONAGEERA GENESIS AMBERWAVE MOONLIGHT SHADOW 17/01/1995 Clear AMESCOT RAMSSES P3635204P03 11/06/1989 Dog SHADANCY SEAHAWK OF SHIRIDER GAMEGIRL OF AMESCOT 17/01/1995 Clear AMESCOT ANDLEY JAMESTONE ADORATION P0865901P01 23/01/1989 Bitch ANDLEY ASPIRE ANDLEY ENCORE AT JAMESTONE 17/01/1995 Clear ANIARA (IMP SWE) AC0900484 10/05/1999 Bitch EMBER JAMES BOND COPPER'S HONEYSUCKLE ROSE 23/01/2003 Clear ANIAS SCARLET AJ04682601 23/08/2008 Bitch LUSCA RIPP (IKC) CREG JANE (IKC) 06/09/2012 Clear ANLORY ANTOINETTE AS03938711 30/09/2015 Bitch ROMARNE CLARK GABLE JOINS BERFIELD KAITLYN JOINS ANLORY 12/03/2018 Clear ANLORY ANLORY CHIANTI DEL BARDONHILL AC01010407 25/01/2002 Bitch SHENANAGIN SOME MIGHT SAY ANLORY RED BEAUJOLAIS 03/11/2003 Clear IT'S BARDONHILL ANLORY CORAL EXPRESS VIA BARDONHILL Z1508501Z02 01/01/1999 Bitch CASPIANS INTREPID -

Gold Coast National Racehorse Sale Supplementary 9 June 2016 Gold Coast Sales Complex, Queensland, Australia Proud Sponsor of the 2016 Magic Millions

GOLD COAST NATIONAL RACEHORSE SALE SUPPLEMENTARY 9 JUNE 2016 GOLD COAST SALES COMPLEX, QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA PROUD SPONSOR OF THE 2016 MAGIC MILLIONS Jeep® is a registered trademark of Chrysler Group LLC. CHECK OUT THE BEST LIVE EVENTS ON THE GOLD COAST Whether it’s surfing, swimming or simply sunbaking, the Gold Coast offers 21 patrolled beaches along its 57 kilometres of pristine coastline. For those who love nature, head inland to the Hinterland with great walking tracks, rock pools and waterfalls. There’s a range of things to do in Australia’s capital of fun. 2016 Australian Viva Surfers Open - Lawn Bowls Paradise 11 – 24 Jun 8 – 17 Jul Gold Coast Airport Swell Sculpture Marathon Festival 2 – 3 Jul 9 – 18 Sep Broadbeach Peaks Challenge Country Music Gold Coast Festival 14 Aug 17 – 19 June See the full event calendar at queensland.com/events 5$&(+256(6 LOTS - TO FOLLOW LOT 7+856'$< JUNE VENDOR INDEX Lot Colour Sex Breeding On Account of Amarina Farm, Denman, NSW. (As Agent) (Stable P 1) 2082 Bay Filly Stalker by Wanted On Account of Dangerous Desire Syndicate, Sunshine Coast, Qld. (Stable P 2) 2088 Grey Filly Dangerous Desire by Bradbury's Luck On Account of Heinrich Racing Stables, Gold Coast, Qld. (Stable QA) 2083 Grey Mare Strawberry Crush by Zizou 2086 Bay Mare Zippity Lass by Zizou 2089 Chestnut Mare Direct Quote by Choisir On Account of JD Thoroughbreds, Beaudesert, Qld. (As Agent) (Stable P 3) 2080 Bay or Brown Mare Murtajewel by Murtajill On Account of Kingsportz Pty Ltd, Murwillumbah, NSW. (As Agent) (Stable Q ) 2084 Chestnut Gelding Super Puma by Rothesay 2090 Bay Filly Electric Kimbo by Charge Forward On Account of Liberty Island Syndicate, Sydney, NSW. -

Ducks and Deer, Profit and Pleasure: Hunters, Game and the Natural Landscapes of Medieval Italy Cristina Arrigoni Martelli A

DUCKS AND DEER, PROFIT AND PLEASURE: HUNTERS, GAME AND THE NATURAL LANDSCAPES OF MEDIEVAL ITALY CRISTINA ARRIGONI MARTELLI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO ONTARIO May 2015 © Cristina Arrigoni Martelli, 2015 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an ample and thorough assessment of hunting in late medieval and Renaissance northern and central Italy. Hunting took place in a variety of landscapes and invested animal species. Both of these had been influenced by human activities for centuries. Hunting had deep cultural significance for a range of social groups, each of which had different expectations and limitations on their use of their local game animal-habitat complexes. Hunting in medieval Italy was business, as well as recreation. The motivations and hunting dynamics (techniques) of different groups of hunters were closely interconnected. This mutuality is central to understanding hunting. It also deeply affected consumption, the ultimate reason behind hunting. In all cases, although hunting was a marginal activity, it did not stand in isolation from other activities of resource extraction. Actual practice at all levels was framed by socio-economic and legal frameworks. While some hunters were bound by these frameworks, others attempted to operate as if they did not matter. This resulted in the co-existence and sometimes competition, between several different hunts and established different sets of knowledge and ways to think about game animals and the natural. The present work traces game animals from their habitats to the dinner table through the material practices and cultural interpretation of a variety of social actors to offer an original survey of the topic.