SOME NOTES on SPRUCE GROUSE (Dendragapus Canadensis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Rivermud

TRIP LISTINGS: 3 - 11 RUMBLINGS: 2, ARTICLE: 1 CharlesTHE River Mud APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN CLUB / BOSTON CHAPTER :: www.amcboston.org August 2010 / Vol. 35, No. 8 ARTICLE By Fruzsina Veress Accidents Happen: A Hiker Offers Thanks to Her Rescuers Watch out for the Leg! Lift the Leg! Pull the Leg to the right! the hut and ask for help. Indeed, we were happy when they The Leg was MY leg, hanging uselessly in its thick bandage called later to say that they had met the two valiant caretak- made from a foam mattress. Suspended by a rope, the Leg ers from Madison Hut on their way to reach us. After about was being handled by one of my heroic rescuers while its two hours of anxious waiting spent mostly hunting down rightful owner crept along behind on her remaining three mosquitoes, the two kind AMC-ers arrived. They splinted limbs (and butt) like a crab led on a leash. The scenery was my ankle, and to protect it from bumping into the boulders, beautiful, the rocky drops of King Ravine. they packaged it into the foam mattress. Earlier on this day, June 28, Nandi and Marton were pre- climbing happily over the pared to piggyback me down boulder field, hoping to reach the ravine, but most of the the ridge leading to Mount ‘trail’ simply consists of blaz- Adams in the White Moun- es painted on the rock, and it tains of New Hampshire, I is next to impossible for two took a wrong step. There was or more people to coordinate a pop, and suddenly my foot their steps. -

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region FOR TOLL-FREE RESERVATIONS 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 20 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com Your Camping Get-Away Starts Here! Outdoor spaces and smiling faces. Fishing by the river under shade trees. These are what makes your get-away adventures come alive with ease. In a tent, with a fox, in an RV with a full utility box. Allow vacation dreams to put you, sunset, at the boat dock. Glamp with your sweetie in a Tipi, or arrive with your dogs, flop down and live-it-up, in a deluxe lodge. Miles of trails for a ramble and bike. Journey down the mile to the White Mountains for a leisurely hike. We’ve a camp store, recreation, food service, Native American lore. All you have to do is book your stay, spark the fire, and you’ll be enjoying s’mores. Bring your pup, the kids, the bikes, and your rig. Whatever your desire of camping excursion, we’ve got you covered with the push of a button. Better yet, give us a call and we’ll take care of it all. Every little things’ gonna be A-Okay. We’ve got you covered in our community of Chocorua Camping Village KOA! See you soon! Unique Lodging Camp Sites of All Types Vacation for Furry Family! Outdoor Recreation Check out our eclectic selection of Tenting, Water Front Patio Sites, Full- Fully Fenced Dog Park with Agility Theme Weekends, Daily Directed lodging! hook-up, Pull-thru – We’ve got you Equipment, Dog Beach and 5 miles of Activities, Ice Cream Smorgasbords, Tie covered! trails! Happy Pups! Dye! Come join the Summer Fun! PAGE 4, 5 & 6 PAGE 5 & 6 PAGE 2 & 20 PAGE 8 & 9 CHOCORUA CAMPING VILLAGE At Your Service Facilities & Activities • NEW! Food Service at the Pavilion! • Tax- Free “Loaded” campstore • Sparkling Pool with Chaise Lounges • 15,000sq.ft. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

^ R ^ ^ S . L O N G I S L a N D M O U N T a I N E E R NEWSLETTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER NOVEMBER

LONG ISLAND ^r^^s. MOUNTAINEER NEWSLETTER OF THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1996 ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER 1995-1996 P^akJ^e/hX^ P<e/K EXECUTIVE COMITTEE PRESIDENT Rich Ehli 735-7363 VICE-PRESIDENT Jem' Kirshman 543-5715 TREASURER Bud Kazdan 549-5015 SECRETARY Nanov Hodson 692-5754 GOVERNOR Herb Coles 897-5306 As I write this, over fifty members and some objective yardstick, I'm afraid GOVERNOR June Fait 897-5306 friends of the chapter are preparing for many of us would be priced out of the BOARD OF DIRECTORS LI-ADK's annual Columbus Day trip to market for outdoor adventure. If you Carol Kazdan 549-5015 Tracy Clark 549-1967 Ann Brosnan 421-3097 Pauline Lavery 627-5605 the Loj. In most years since joining the have thought about attending our week Don Mantell 598-1015 Jem' Licht 797-5729 club ten years ago, I have enjoyed the end outings, go ahead and give it a try - COMMITEE CHAIRS camaraderie of hiking in the High Peaks you really don't know what you're miss CONSERVATION June Fait 897-5306 HOSPITALITY Arlene Scholer 354-0231 with my hardy and fun-loving fellow ing. ^ MEMBERSHIP Joanne Malecki 265-6596 ADKers on what has often been a spec On the eve before our departure for the MOUNTAINEER Andrew Heiz 221-4719 OUTINGS WE NEED A VOLUNTEER tacular fall weekend. Like me, many of Loj, we will be gathering at Bertucci's PROGRAMS Yetta Sokol 433-6561 the trippers to the fall outing are repeat restaurant in Melville for our annual din PUBLICITY Arlene Scholer 354-0231 ers. -

Fall 1997 Vol. 16 No. 3

NevnHomprhire Bird Records Foll | 997 Vol. | 6, No. 3 Fromrhe Ediror We are pleased to honor Kimball Elkins in this issue of New Hampshire Bird Records. Kimball was the Fall Editor for many years and later served as Technical Editor until his death in Septemberof L997. All of us will miss Kimball, who was not only a valuable resourceon birds in the statebut also a wonderful person. A special thank you to SusanFogleman for the cover illustration of a Barred Owl which originally appearedinlhe Atlas of Breeding Birds in New Hampshire. Susan's artworkmaybefoundthroughoutthisissueofNewHampshireBirdRecordsinmemory of Kimball Elkin's friendship and mentoring. We appreciate the support of the donors who sponsoredthis issue in Kimball's memory. Donations may also be made in Kimball's honor to a fund for the revision of his Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire. Pleasecontact me at 224-9909 for more information. BeclcySuomala Managing Editor New HampshirizBird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by the Audubon Society of New Hampshire (ASNH). Bird sightings are submitted to ASNH and are edited for publication. A computerized printout of all sightings in a seasonis available for a fee. To order a printout, purchaseback issues,or volunteer your observationsfor NfIBR, please contact the Managing Editor at224-9909. We are always interested in receiving sponsorshipfor NH Bird Records. If you or a company/organization you work for would be interested, pleasecontact Becky Suomalaat224-9909. Published by rhe Audubon Society of New Hompshire New Hampshire Bird Records @ ASNH 1998 \!rd^@^ Printedon RecycledPaper Dedicofion Kimball Elkins, a long-time editor of New Hampshire Bird Records, loved birds and birding. -

Grouse of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, by Michael A. Schroeder

WashingtonHistory.org GROUSE OF THE LEWIS & CLARK EXPEDITION By Michael A. Schroeder COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Winter 2003-04: Vol. 17, No. 4 “The flesh of the cock of the Plains is dark, and only tolerable in point of flavour. I do not think it as good as either the Pheasant or Grouse." These words were spoken by Meriwether Lewis on March 2, 1806, at Fort Clatsop near present-day Astoria, Oregon. They were noteworthy not only for their detail but for the way they illustrate the process of acquiring new information. A careful reading of the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark (transcribed by Gary E. Moulton, 1986-2001, University of Nebraska Press) reveals that all of the species referred to in the first quote are grouse, two of which had never been described in print before. In 1803-06 Lewis and Clark led a monumental three-year expedition up the Missouri River and its tributaries to the Rocky Mountains, down the Columbia River and its tributaries to the Pacific Ocean, and back again. Although most of us are aware of adventurous aspects of the journey such as close encounters with indigenous peoples and periods of extreme hunger, the expedition was also characterized by an unprecedented effort to record as many aspects of natural history as possible. No group of animals illustrates this objective more than the grouse. The journals include numerous detailed summary descriptions of grouse and more than 80 actual observations, many with enough descriptive information to identify the species. What makes Lewis and Clark so unique in this regard is that other explorers of the age rarely recorded adequate details. -

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region For Toll-Free reservaTions 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 19 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com We Trust That You’ll Our Awesome Park! Escape the noisy rush of the city. Pack up and leave home on a get-away adventure! Come join the vacation tradition of our spacious, forested Chocorua Camping Village KOA! Miles of nature trails, a lake-size pond and river to explore by kayak. We offer activities all week with Theme Weekends to keep the kids and family entertained. Come by tent, pop-up, RV, or glamp-it-up in new Tipis, off-the-grid cabins or enjoy easing into full-amenity lodges. #BringTheDog #Adulting Young Couples... RVers Rave about their Families who Camp Together - Experience at CCV Stay Together, even when apart ...often attest to the rustic, lakeside cabins of You have undoubtedly worked long and hard to earn Why is it that both parents and children look forward Wabanaki Lodge as being the Sangri-La of the White ownership of the RV you now enjoy. We at Chocorua with such excitement and enthusiasm to their frequent Mountains where they can enjoy a simple cabin along Camping Village-KOA appreciate and respect that fact; weekends and camping vacations at Chocorua Camping the shore of Moores Pond, nestled in the privacy of a we would love to reward your achievement with the Village—KOA? woodland pine grove. -

2018 White Mountains of Maine

2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Handbook 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! We are thrilled that you have chosen to join us this summer at the Sunday River Resort in the White Mountains of Maine! Whether this is your first time or your fifteenth, we know you appreciate the unparalleled value your family receives from attending a Family Nature Summit. One of the aspects that is unique about the Family Nature Summits program is that children have their own program with other children their own age during the day while the adults are free to choose their own classes and activities. Our youth programs are run by experienced and talented environmental educators who are very adept at providing a fun and engaging program for children. Our adult classes and activities are also taught by experts in their fields and are equally engaging and fun. In the afternoon, there are offerings for the whole family to do together as well as entertaining evening programs. Family Nature Summits is fortunate to have such a dedicated group of volunteers who have spent countless hours to ensure this amazing experience continues year after year. This handbook is designed to help orient you to the 2018 Family Nature Summit program. We look forward to seeing you in Maine! Page 2 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Table of Contents Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! 2 Summit Information 7 Summit Location 7 Arrival and Departure 7 Room Check-in 7 Summit Check-in 7 Group Picture 8 Teacher Continuing Education -

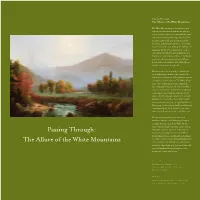

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

North American Game Birds Or Animals

North American Game Birds & Game Animals LARGE GAME Bear: Black Bear, Brown Bear, Grizzly Bear, Polar Bear Goat: bezoar goat, ibex, mountain goat, Rocky Mountain goat Bison, Wood Bison Moose, including Shiras Moose Caribou: Barren Ground Caribou, Dolphin Caribou, Union Caribou, Muskox Woodland Caribou Pronghorn Mountain Lion Sheep: Barbary Sheep, Bighorn Deer: Axis Deer, Black-tailed Deer, Sheep, California Bighorn Sheep, Chital, Columbian Black-tailed Deer, Dall’s Sheep, Desert Bighorn Mule Deer, White-tailed Deer Sheep, Lanai Mouflon Sheep, Nelson Bighorn Sheep, Rocky Elk: Rocky Mountain Elk, Tule Elk Mountain Bighorn Sheep, Stone Sheep, Thinhorn Mountain Sheep Gemsbok SMALL GAME Armadillo Marmot, including Alaska marmot, groundhog, hoary marmot, Badger woodchuck Beaver Marten, including American marten and pine marten Bobcat Mink North American Civet Cat/Ring- tailed Cat, Spotted Skunk Mole Coyote Mouse Ferret, feral ferret Muskrat Fisher Nutria Fox: arctic fox, gray fox, red fox, swift Opossum fox Pig: feral swine, javelina, wild boar, Lynx wild hogs, wild pigs Pika Skunk, including Striped Skunk Porcupine and Spotted Skunk Prairie Dog: Black-tailed Prairie Squirrel: Abert’s Squirrel, Black Dogs, Gunnison’s Prairie Dogs, Squirrel, Columbian Ground White-tailed Prairie Dogs Squirrel, Gray Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Fox Squirrel, Ground Rabbit & Hare: Arctic Hare, Black- Squirrel, Pine Squirrel, Red Squirrel, tailed Jackrabbit, Cottontail Rabbit, Richardson’s Ground Squirrel, Tree Belgian Hare, European -

June 24, 2021

PRSRT STD Belchertown, Granby & Amherst U.S. POSTAGE PAID PALMER, MA PERMIT NO. 22 ECR-WSS LOCAL POSTAL CUSTOMER THURSDAY, JUNE 24, 2021 ENTINELYOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1915 A TURLEY PUBLICATIONS ❙ www.turley.com Volume 106 • Number 14 www.sentinel.turley.com COMMUNITY OPINION AGRICULTURE SPORTS Dreamer the Lemur...p. 4 A missed sign spoils Finger licking Orioles enter the surprise...p. 6 picking...p. 8 tournament...p. 11 GOVERNMENT Rustic Fusion, owned by Chris Snow, was one of COVID relief four food trucks that came to Food Truck Fridays funds coming; on June 18. How it will be used is TBD JONAH SNOWDEN [email protected] REGION – As the Mass. Senate and House work to reconcile differences and craft a new state bud- get to send on to Gov. Charlie Baker, the Baker administration last week announced a plan to spread approximately $2.815 billion in direct federal aid among local municipalities to target communities that could use an economic boost. “Key priorities” include housing and homeowner- Finally, it’s ship, economic development, local downtowns, job training, workforce development, health care, and infrastructure, Baker said. The money was doled out to states in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the negative impact it has had on local economies. “Our proposal will immediately invest $2.8 bil- FOOD TRUCK FRIDAYS lion toward key priorities that will help jump-start our economic recovery, with a particular focus on CARA McCARTHY those hit hardest by COVID-19, such as communi- Staff writer ties of color,” Baker said in a statement. “With over four million people fully vaccinated, Massachusetts BELCHERTOWN -- Food Truck Tess Mathewson, is getting back to normal and back to work, but it is Fridays have made a return to the Parker Mas, and critical that we act now to make these critical invest- Town Common as the COVID-19 Olive Smith coor- ments to keep our recovery moving. -

Street • North Conway Village (Across from Joe Jones) • 356-5039 “Life Is Good”

VOLUME 33, NUMBER 8 JULY 10, 2008 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY All Eight in ’08: Steve Caming visits Carter Notch Hut, the first of the eight AMC huts he plans to explore this summer … A 6 Alpine Disc Golf: Wildcat Ski Area offers a new, lift-serviced, attraction for the summer A 15 Arts Jubilee Begins 26th Season: This summer’s lineup of outdoor entertainment begins July 17 … B1 As The Wheels Turn: Hundreds of bicyclists will be gathering in Fryeburg for the Maine Jackson, NH 03846 • Lodging: 383-9443 • Recreation: 383-0845 Bike Rally … www.nestlenookfarm.com • 1-800-659-9443 B16 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH SSTTOORRYY LLAANNDD On Second Thought CC OO RR NN EE RR The tradition Down for now - Up again in 2010 continues at... Jackson’s Trickey Barn continues its journey By Steven Caming Jackson Grammar School students is touchstone and community rallying Contributing Writer also being produced and will be available point in Jackson and like an old friend, IT WAS A DAY OF CELEBRA- locally. will not be forgotten until it can be seen tion, remembrance and excitement as Somehow, this old barn has become a again. ▲ more than 75 Jackson residents gathered recently to witness the ceremonial Where there's a smile & beginning of the dismantling process of Jackson’s most historic barn. The adventure around every corner! Trickey Barn was built 150 years ago and has stood in the center of the village since then. New this summer The morning’s activities included three parts: a ribbon unfurling across the at Story Land barn doors, which officially sealed the barn.