Enter Paper Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

{Download PDF} Goodbye 20Th Century: a Biography of Sonic

GOODBYE 20TH CENTURY: A BIOGRAPHY OF SONIC YOUTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Browne | 464 pages | 02 Jun 2009 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306816031 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century - Wikipedia He was also in the alternative rock band Sonic Youth from until their breakup, mainly on bass but occasionally playing guitar. It was the band's first album following the departure of multi-instrumentalist Jim O'Rourke, who had joined as a fifth member in It also completed Sonic Youth's contract with Geffen, which released the band's previous eight records. The discography of American rock band Sonic Youth comprises 15 studio albums, seven extended plays, three compilation albums, seven video releases, 21 singles, 46 music videos, nine releases in the Sonic Youth Recordings series, eight official bootlegs, and contributions to 16 soundtracks and other compilations. It was released in on DGC. The song was dedicated to the band's friend Joe Cole, who was killed by a gunman in The lyrics were written by Thurston Moore. It featured songs from the album Sister. It was released on vinyl in , with a CD release in Apparently, the actual tape of the live recording was sped up to fit vinyl, but was not slowed down again for the CD release. It was the eighth release in the SYR series. It was released on July 28, The album was recorded on July 1, at the Roskilde Festival. The album title is in Danish and means "Other sides of Sonic Youth". For this album, the band sought to expand upon its trademark alternating guitar arrangements and the layered sound of their previous album Daydream Nation The band's songwriting on Goo is more topical than past works, exploring themes of female empowerment and pop culture. -

Russie. Adele, U2, Madonna, Yoko Ono, Radiohead, Patti Smith, Bruce

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Lettre ouverte Index AI : EUR 46/031/2013 AILRC-FR 22 juillet 2013 Adele, U2, Madonna, Yoko Ono, Radiohead, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, Ke$ha, Paul McCartney et Sting se joignent à plus de 100 musiciens pour réclamer la libération des Pussy Riot Chères Macha et Nadia, À l’approche du premier anniversaire de votre procès, nous tenions à vous écrire pour vous assurer que, partout dans le monde, des gens continuent de penser à vous et d’œuvrer à votre libération. Si vous étiez les contestataires les plus visibles, nous savons que beaucoup d’autres jeunes ont souffert durant les manifestations, et nous restons très préoccupés à leur sujet. Toutefois, à bien des égards, à travers votre incarcération, vous incarnez désormais cette jeunesse. De nombreux artistes ont exprimé leur inquiétude lorsque ces accusations ont été portées contre vous ; nous espérions vraiment que les autorités, dans cette affaire, feraient preuve d’un certain degré de compréhension, du sens des proportions, et même du sens de l’humour russe si caractéristique, mais force est de constater qu’il n’en fut rien. Votre procès terriblement inique et votre incarcération ont eu un très grand retentissement, particulièrement au sein de la communauté des artistes, des musiciens et des citoyens dans le monde entier, et notamment auprès des parents qui ressentent votre angoisse d’être séparées de vos enfants. Tout en comprenant qu’une action de contestation menée dans un lieu de culte puisse choquer, nous demandons aux autorités russes de revoir les sentences très lourdes prononcées, afin que vous puissiez retrouver vos enfants, vos familles et vos vies. -

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation

The Golden Age of Non-Idiomatic Improvisation FYS 129 David Keffer, Professor Dept. of Materials Science & Engineering The University of Tennessee Knoxville, TN 37996-2100 [email protected] http: //cl ausi us.engr.u tk.e du / Various Quotes These slides contain a collection of some of the quotes largely from the musicians that are studied during the course. The idea is to present “musicians in their own words”. Thurston Moore American guitarist and vocalist (July 25, 1958—) Background on Sonic Youth Thurston Moore was a guitarist and vocalist for Sonic Youth. Sonic Youth was an American alternative rock band from New York City, formed in 1981. Their lineup largely consisted of Thurston Moore (guitar and vocals), Kim Gordon (bass guitar, vocals, and guitar), Lee Ranaldo (guitar and vocals), Steve Shelley (drums). In their early career, Sonic Youth was associated with the no wave art and music scene in New York City. Part of the first wave of American noise rock groups, the band carried out their interpretation of the hardcore punk ethos throughout the evolving American underground that focused more on the DIY ethic of the genre rather than its specific sound. As a result, some consider Sonic Youth as pivotal in the rise of the alternative rock and indie rock movementThbdts. The band exper ience d success an ditild critical acc lithhtlaim throughout their existence, continuing into the new millennium, including signing to major label DGC in 1990, and headlining the 1995 Lollapalooza festival. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonic_youth Moore Quotes Q: What led Sonic Youth to do a project like Goodbye 20th Century? Moore: It was definitely a universe or world that we were aware of. -

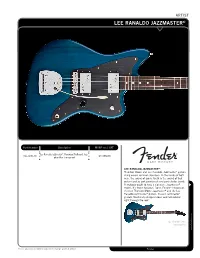

Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster®

ARTIST LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER® Part Number Description MSRP excl. VAT Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster®, Rosewood Fretboard, Sap- 011-5100-727 phire Blue Transparent €1,895.00 LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER®: Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo. Jazzmaster® guitars slung across seminal shoulders. In the hands of both men, the sound of Sonic Youth is the sound of that guitar used as part paintbrush and part cluster bomb. If anybody ought to have a signature Jazzmaster® model, it’s those two guys. Done. Fender® introduces the new Thurston Moore Jazzmaster® and the Lee Ranaldo Jazzmaster® guitars. Classic Jazzmaster® gestalt, Youth-fully stripped down and hot rodded right through the roof. 727 (Saphire Blue Transparent) www.fender.com Prices and specifications subject to change without notice. Fender ARTIST LEE RANALDO JAZZMASTER® COLORS: (727) parent Saphire Blue Trans- SPECIFICATIONS: Body Alder Finish Satin Nitrocellulose Lacquer Finish Neck Maple w/ Satin Black Painted Headstock, “C” Shape Fingerboard Rosewood, 7.25” Radius (184 mm) Frets 21, Vintage Style Scale Length 25.5” Nut Width: 1.650” Hardware Chrome Tuning Keys Fender® Vintage Style Tuning Machines Bridge American Vintage Jazzmaster® Tremolo with Mustang® Bridge and Tremolo Lock Button. Pickguard Anodized Black Pickups 2 New Fender® Wide Range Humbucking Pickups Re- Voiced to Original Vintage Spec, (Neck/Bridge) Pickup Switching 3-Position Toggle: Position 1. Bridge Pickup Position 2. Bridge and Neck Pickups Position 3. Neck Pickup Controls Master Volume (Neck and Bridge Pickup) Strings Fender® Standard Tension™ ST250R, Nickel Plated Steel, Gauges: (.010, .013, .017, .026, .036, .046), (p/n 0730250206) Incl. Accessories Case: Standard Tolex Case Accessories: Strap, Cable, Jazzmaster Strings®, Sonic Youth ‘Zine, Sticker Sheet Unique Features Satin Lacquer Finish, Satin Black Painted Headstock, Single 727 (Saphire Blue Transparent) Master Volume, Mustang® Style Bridge, Re-Voiced Wide Range Humbucking pickups, Black Anodized Aluminum Pickguard, Sticker Sheet. -

Post-Cinematic Affect: on Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales

Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Post-Cinematic Affect: On Grace Jones, Boarding Gate and Southland Tales Steven Shaviro Wayne State University Introduction In this text, I look at three recent media productions – two films and a music video – that reflect, in particularly radical and cogent ways, upon the world we live in today. Olivier Assayas’ Boarding Gate (starring Asia Argento) and Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales (with Justin Timberlake, Dwayne Johnson, Seann William Scott, and Sarah Michelle Gellar) were both released in 2007. Nick Hooker’s music video for Grace Jones’s song ‘Corporate Cannibal’ was released (as was the song itself) in 2008. These works are quite different from one another, in form as well as content. ‘Corporate Cannibal’ is a digital production that has little in common with traditional film. Boarding Gate, on the other hand, is not a digital work; it is thoroughly cinematic, in terms both of technology, and of narrative development and character presentation. Southland Tales lies somewhat in between the other two. It is grounded in the formal techniques of television, video, and digital media, rather than those of film; but its grand ambitions are very much those of a big-screen movie. Nonetheless, despite their evident differences, all three of these works express, and exemplify, the ‘structure of feeling’ that I would like to call (for want of a better phrase) post-cinematic affect. Film-Philosophy | ISSN: 1466-4615 1 Film-Philosophy 14.1 2010 Why ‘post-cinematic’? Film gave way to television as a ‘cultural dominant’ a long time ago, in the mid-twentieth century; and television in turn has given way in recent years to computer- and network-based, and digitally generated, ‘new media.’ Film itself has not disappeared, of course; but filmmaking has been transformed, over the past two decades, from an analogue process to a heavily digitised one. -

DISTRIBUXIOIM TOPINDIESINGLES 1 . T 1 SHOULD BE SO LUCKY Kylie Minogue PWL PWL(F|8 (P) 2Mi BEAT DIS Mister-Ron/Rhythm King/ Bomb

DISTRIBUXIOIM TOPINDIESINGLES 1 . 1 SHOULD BE SO LUCKY w ,s „ MY BABY JUST CARES FOR ME 35 CE3 Mea^ealMonife^sto" Sweatbo* SOX023 (l/RT) t KylieBEAT Minogue DIS Mister-ron/RhythmPWL PWL(F|8 King/ (P) 2mi Bomb The Bass Mule 0000(1211 (l/RT) IS'** 22 , TheLAST Smiths NIGHT 1 DREAMT Rough... Trade RT(T)200 (l/RT) 36 " -SLLTEARUSAPART^^^Sk5MONS 3 ' ' ROK DA HOUSE Rhytbm King/Mule LEFTIlfT) (l/RT) ' lO,y ,2 M3? THEErasure CIRCUS (Remix) Mule (1)MUTE66(T) (l/RT/SP) 37...^ Shange Fruit—,SFPS033, (P, TbeDOCTORIN'THE Beolmaslcrs featuring HOUSE The Cookie Ahead Crew 01 Our Time 30 ^34 „ THE PEEL SESSIONS (VOLUME S) 4CE3 Cold Cut leal. Yocz & Plastic People CCUT2 (l/RTI 20 20 S JACKMirage MIX IV Debut DEBT(X)3035 (A) 38 " New Order0WN Strange Fruit-(SFPS^P) (P) 5 lCSIjj ANIMAL (F... LIKE A BEAST) , 21 .. s JINGOCandida Hardcore HAK(T)9 (A) 39" 17 Derek B Music Of Life NOTE 007 (P) J ® WCOLD.A.S.P. SWEAT Music For Notions (12)KUT 109 (P) 0 GNTHUR5DAY 6 3 3 The Suqarcubes One Utllc Indian (12)TP9 (l/NM) 22 .o 4 MASTERSonic Youth DIK Blast First BFFP26(T) (l/RT) 40l^!?24 2 m JilGABES Ca,&MouseABBO,m(P, •! 7 mi HitmaslersSAWMIX 1 Quazor QUA(T)5 (P) 23 csatuuuj Smanyone.|h & Mi9hty Tllree Stripe SAM1, , (|/RE) 41 a s CastawayTR27 (A) ; 81:23o rm DANCING AND MUSIC (MUSIC PLEASE) 24 u 22 BIRTHDAY 42 » ' SisrereOf Mercy Merciful ReleaseMR021 (l/RR) Groove Submi5siort-|SUBX04)(I/RT) J The Sugarcubes One Utlle Indian (12) 7TP7 (l/NM) 4333MO „ JheGIRLFRIEND Smiths IN A COMARough Trade RT(T) 197 (l/RT) j 9 ^ THEREPop Will EatIS NOItself LOVE BETWEENChapter 22 (12)CHAP20 US ANYMORE (l/NM) n*"OK ,i is EriaSAVIN' Fachin MYSELF Saturday 7STD1 (12--STD1)(A) 5 10 ' ' WoodentopsYOU MAKE ME FEEL Rough Trade RT(T)179 (l/RT) 26 rmLLUI Doqst)HOW. -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

Olivier Assayas

[email protected] • www.janusfilms.com “No one sees anything. Ever. They watch, but they don’t understand.” So observes Connie Nielsen in Olivier Assayas’s hallucinatory, globe-spanning demonlover, a postmodern neonoir thriller and media critique in which nothing—not even the film itself—is what it appears to be. Nielsen plays Diane de Monx, a Volf Corporation executive turned spy for rival Mangatronics in the companies’ battle over the lucrative market of internet adult animation. But Diane may not be the only player at Volf with a hidden agenda: both romantic interest Hervé (Charles Berling) and office enemy Elise (Chloë Sevigny) seem to know her secret and can easily use it against her for their own purposes. As the stakes grow higher and Diane ventures into deadlier territory, and as Sonic Youth’s score pulses, Assayas explores the connections between multinational businesses and extreme underground media as well as the many ways twenty-first-century reality increasingly resembles violent, disorienting fiction. New 2K restoration of the unrated director’s cut overseen by Olivier Assayas France | 2002 | 122 minutes | Color | In Japanese, French, and English with English subtitles | 2.35:1 aspect ratio Booking Inquiries: Janus Films Press Contact: Courtney Ott [email protected] • 212-756-8761 [email protected] • 646-230-6847 OLIVIER ASSAYAS Olivier Assayas was born in Paris in 1955, the son of screenwriter sentimentales (2000), demonlover (2002), and Clean (2004) were Raymond Assayas (better known by the pen name of Jacques all nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes, while Summer Rémy). After studying painting at the French National School of Hours (2008) and the miniseries Carlos (2010) each earned Fine Arts and working as a critic for Cahiers du cinéma, Assayas multiple awards from various international festivals and societies. -

Sonic Youth Starpower Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sonic Youth Starpower mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Starpower Country: US Released: 1991 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1887 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1149 mb WMA version RAR size: 1745 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 332 Other Formats: MMF MP4 ASF AC3 MIDI FLAC VOX Tracklist Hide Credits A Starpower (Edit) 2:50 Bubblegum B1 2:45 Bass – Mike WattWritten-By – Kim Fowley, Marty Cert* B2 Expressway (Edit) 4:30 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – SST Records Copyright (c) – Savage Conquest Music Copyright (c) – Kim Fowley Music Mastered At – K Disc Mastering Mastered At – Greg Lee Processing – L-37312 Pressed By – Rainbo Records – S-24767 Pressed By – Rainbo Records – S-24768 Credits Mastered By – JG* Photography By [Photos] – Lazy Eight, Lee* Words By, Music By – Sonic Youth Notes ℗ 1986 SST Records, P.O. Box 1 Lawndale, CA 90260 © 1986 Savage Conquest (ASCAP) (except "Bubblegum" Cert + Fowley, Kim Fowley Music (BMI)) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 18861-0909-1 7 Matrix / Runout (Etchings side A): SST-909-A S-24767 kdisc JG L-37312 Matrix / Runout (Etchings side B): SST-909-B S-24768 kdisc JG L-37312X Rights Society: ASCAP Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SST 080 Sonic Youth Starpower (12", Single) SST Records SST 080 US 1986 SST 909 Sonic Youth Starpower (10", Single, Bro) SST Records SST 909 US 1991 BFFP 7 Sonic Youth Starpower (7", Ltd) Blast First BFFP 7 UK 1986 BFFP7 Sonic Youth Starpower (7", Single) Blast First BFFP7 UK 1986 SST 909 Sonic Youth Starpower (10", Single, Gra) SST Records SST 909 US 1991 Related Music albums to Starpower by Sonic Youth Starpower - Stargirl A Host Of Stars - I't OK To Say No! Dinosaur Jr. -

7Pm Apexart:291 Church Street, New York, NY

Come Together (NYC) Apexart asked me to be a part of a show called Maurizio Couldn’t Be Here. For five weeks in February and March the gallery is hosting a different performance related project each week. I came up with an idea for the first week. What I decided to do is organize an all day lecture program com- posed of 26 people who will each lecture for ten minutes a piece. The entire event will be video taped and shown as a projection in the gallery the following week. I asked 26 people who I knew or who knew someone I knew to select someone else to do one of the ten minute lectures. The selectors supplied info about the lectures for this publica- tion and will introduce their lecturers at the event. The only requirements I had for the people doing lectures was that they didn’t ordinarily go to Apexart and that the topic that they chose to lecture on was not directly related to contem- porary visual art. Otherwise the lecturer could be anyone in the NYC area and the lecture topics were totally open. The lectures will be presented in the following order beginning at 11 am and ending at 7 pm on Saturday, February 12th at the gallery. There will be periodic breaks and snacks pro- vided. The public is invited to attend the entire eight hour event, but can feel free to come and go between lectures. – Harrell Fletcher 26 ten minute lectures by 26 different people Saturday, February 12, 2005 11am – 7pm Apexart: 291 Church Street, New York, NY 2 Presentation On The Kemetic Orthodox Religion Josh Kline will lecture about The Kemetic Orthodox Church which he feels is one of the most interesting new religions in America today. -

Kolaj Spring 2014

Kolaj A. Fairlie, ’Modern-day Witch of L.A.: A Profile of Marnie Weber’ Spring 2014, p. 2 - 7 Running Away by Marnie Weber 95.75"x75.75" collage on light jet print 2007 courtesy of the artist Photo: LeeAnn Nickel Kolaj A. Fairlie, ’Modern-day Witch of L.A.: A Profile of Marnie Weber’ Spring 2014, p. 2 - 7 Modern-day Witch of L.A. A Profile of Marnie Weber by Ariane Fairlie “When your subconscious is creating dreams it creates images & juxtaposes them.” Marnie Weber is a modern-day witch o f Los Angeles. Her diverse artistic practice spans mu- sic, video, performance, costume design, and, of course, collage. Her mythology is spellbind- ing as you become acquainted with her strange characters and domain. Ghostly dolls, clowns, and animals such as bunnies, bears, and mice are all returning roles in her grand narrative. Weber’s imagination is refreshingly youthful; she is prolific but seemingly unencumbered. Driven by longing and romanticism, she delves deeply into her childhood to feed her production. Weber’s engagement with collage coincided with her career in the alternative rock scene, performing with The Party Boys and Perfect Me in the 80’s and afterwards making two solo albums: Woman with Bass (1994) and Cry for Happy (1996). She began her collage practice by creating a limited edition of 100 handmade collages, distributed on one side of her LP album covers. She says the experience was like a boot camp to understand collage. Since then, she has created album covers and promotional posters for many musical acts, most notably the cover for Sonic Youth’s A Thousand Leaves.