Dynamics of Social Change in South Delhi's Hauz Khas Village Lucie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Geneva May 19, 2006 India Habitat Centre, New Delhi Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health * Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Geneva For more information, contact Dr. Deepti Chirmulay Dr. Aparajita Gogoi PATH WRAI A-9, Qutab Institutional Area C/o CEDPA New Delhi–110 067, India C-1, Hauz Khas Tel: 91-11-2653 0080 to 88 New Delhi–110 016, India Fax: 91-11-2653 0089 Tel: 91-11-5165 6781 to 85 Web: www.path.org Fax: 91-11-5165 6710 Email: [email protected] Web: whiteribbonalliance-india.org Email: [email protected] * This report was prepared in June 2006. Report of the national consultation supported by Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, 2 Geneva, organized by PATH and the White Ribbon Alliance. (May 19, 2006, New Delhi, India). Synergies in Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Background • In April 2005, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (PMNCH) was launched at “Lives in the Balance,” a three-day international consultation convened in New Delhi. The consultation culminated with a proclamation of “The Delhi Declaration on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health.” • These global efforts to link and expand efforts on maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) are also reflected in Government of India (GOI) policy, programs and priorities, notably through the National Rural Health Mission and Reproductive and Child Health (RCH–II) program. -

Water Meters Dealers List 19 MAY.Xlsx

DASMESH, DMB Meters. Sr.No. Zone/Area Name Address Contact 1 Central Delhi Chamanlal& Sons 3343, GaliPipalMahadev, HauzQazi, Delhi-110006 011 23270789 2 Central Delhi Mahabir Prasad & Sons 3702, CHAWRI BAZAR, DELHI-110006 011 23263351, 23271750 3 Central Delhi Motilal Jain & Co 3622, Chawri Bazar, Delhi-110006 011 23916843 4 Central Delhi Munshi Lal Om Prakash 3685, Chawri bazar, Delhi-110006 011 32637998, 23265692, 5 Central Delhi SS Corporation 3377, HauzQazi, Delhi-110006 011 23267697 6 Central Delhi Patwariji Agencies Pvt Ltd Shop no. 3314-15, Bank Street, Karol Bagh, Delhi - 011 28723231 110005, Near Karol Bagh Police Station 7 Central Delhi Veenus Enterprises 3852 GaliLoheWali, Chawari Bazar, Delhi 110006 011 23918006 8 East Delhi Raj Trading Company S505, School Block, Shakar Pur, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi- 9871501108 110092 9 East Delhi Vijay Sanitory Store 25/1, G.T. Road, Shadhara, Delhi-110032 22323040, 22323041, 9811060625 10 East Delhi Shri Krishna Paints 3-A., I Pocket., Mangal bazar road, Dilshad Garden, 011 22579456 Delhi-110095 11 East Delhi Sharma Water Supply Co. A-1, Jagat Puri, Shahdara, Delhi-110032 011 22123218 12 North Delhi Giriraj Tiles & Sanitary Empurium A-4/161, Sector 4, Rohini, Delhi - 110085 011 27044107 13 North Delhi Goel Sanitary Store Wp-466, Shiv Market, Wazirpur, Delhi - 110052 9810458161 14 North Delhi Raj Paints & Hardware Store 59, Main Bazar, Kingsway Camp, Delhi-110059 011 27214437 15 North Delhi Veer Sanitary Store C-10, Main Gt Road, Rana Pratap Bagh, Delhi - 110007 011 27436425 16 North DelhiRajilal& Sons 678, Main Bazar, SabziMandi, Delhi-110007 9818854021, 23857240 17 South Delhi Arora Paint & Hardware 1663/D-17, Main Road Kalkaji, Govindpuri, New Delhi- 011 26413291, 110019 6229797 18 South Delhi Durga Sanitary Paint & Hardware B-34-B, Main Road, Kalkaji, Delhi - 110019, Near 011 26225566, Store SagarRatna 41050909 19 South Delhi Kalka Sanitary Store A-57, Double Storey, Main Road, Kalkaji, Delhi - 110019, 011 26430433, Opposite HDFC Bank 26439474 9810094018 20 South Delhi Lakshmi Steel Sanitary & Shop No. -

Seagate Crystal Reports Activex

PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-08-2015 To 31-08-2015 Book No. 1 No. S.No Reg.No. IstParty IIndParty Type of Deed Address Value Stamp Book No. Paid Laxmi Nagar 15143 -- MONIKA ASHA BAGRI SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 400,000.00 16,000.00 1 AREA N-45-A/E ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 8, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 25274 -- NEELAM TYAGI USHA RANI SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 105 4,600,000.00 184,000.00 1 SHARMA AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 63, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 35357 -- MUJIB REHMAN BHAGWAN LAL SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 9/320 5,100,000.00 238,007.00 1 AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 80, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 45392 -- SHEEL RAJ RANI DUBEY SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 5 2,500,000.00 100,000.00 1 CHHABRA AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 84, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 55535 -- KANIZ BEGUM MUNAWWAR SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 104 730,000.00 43,800.00 1 IQBAL AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 11, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 65632 -- CHANDRA GAURAV GARG SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 110/2 5,700,000.00 285,000.00 1 BHATT AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , ATTORNEY OF Area1 84, Area2 0, Area3 SAROJ KUMARI 0 Laxmi Nagar TYAGI 1 of 141 03 September 2015 PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-08-2015 To 31-08-2015 Book No. -

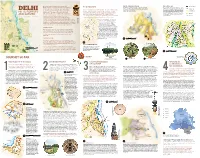

WARD 62-S, HAUZ KHAS Izfrcaf/Kr RESTRICTED Dsoy Fohkkxh; Á;®X Gsrq for DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY ± Fu;Kzr Ds Fy, Ugha NOT for EXPORT

WARD 62-S, HAUZ KHAS izfrcaf/kr RESTRICTED dsoy foHkkxh; Á;®x gsrq FOR DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY ± fu;kZr ds fy, ugha NOT FOR EXPORT SOUTH EXTN. WARDS AS SEEN WITHIN AC-43 (MALVIYA NAGAR) SOUTH EXTENSION PART - II ANSARI NAGAR EAST MASJID MOTH J A IN M UDAY PARK GAUTAM NAGAR A R 62-S_HAUZ KHAS GREEN PARK RWA OFFICE G N. C.R INDIA 61-S_SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEETI BAGH NEW YUSUF SARAI GULMOHAR ENCLAVE GULMOHAR PARK BLOCK B GULMOHAR PARK 63-S_MALVIYA NAGAR DELHI JAL BOARD HAUZ KHAS BLOCK Z HAUZ KHAS BLOCK Y LEGEND HAUZ KHAS BLOCK A [ [ [ Railway Line HAUZ KHAS BLOCK X Bank AUDITORIUM mm HAUZ KHAS BLOCK M C College Canal SIRI INSTITUTIONAL AREA Bus Stop River G R A WARD NO.62-S ñ Auditorium M Storm Water O HAUZ KHAS D Fire Station N Pond I HAUZ KHAS BLOCK C B : O PWD OFFICE =( Metro Station R Sub Locality U A P MAYFAIR GARDEN Bus Terminal Locality E N PADMINI ENCLAVE G A Health Centre L Play Ground E C I HAUZ KHAS ENCLAVE BLOCK K Cats Ambulance V Stadium R E BSES OFFICE S 7m ¯ Community Center Garden Parks HAUZ KHAS k Government Office I I T GATE Ward Boundary Accident Trauma Center Roads AC Boundary SARVAPRIYA VIHAR KALU SARAI BSES OFFICE 310 0 310 620 SARVAPRIYA VIHAR Meters VIJAY MANDAL ENCLAVE BHAVISHYA NIDHI ENCLAVE 1:16,000 MALVIYA NAGAR BLOCK A For further details about this map , please contact BEGAMPUR VILLAGE ADHCHINI Geospatial Delhi Limited SARVODAYA ENCLAVE SARVODYA ENCLAVE SARVODAYA ENCLAVE BLOCK B ADARSH FARM Website : www.gsdl.org.in Disclaimer: Reproduction in whole or part by any means is prohibited without written permission of Geospatial Delhi Limited and State Election Commission Delhi. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Jahanpanah Part of the Sarai Shahji Village As a Place for Travellers to Stay

CORONATION PARK 3. SARAI SHAHJI MAHAL 5. KHARBUZE KA GUMBAD a walk around The Sarai Shahji Mahal is best approached from the main Geetanjali This is an interesting, yet bizarre little structure, Road that cuts through Malviya Nagar rather than from the Begumpur located within the premises of a Montessori village. The mahal (palace) and many surrounding buildings were school in the residential neighbourhood of Jahanpanah part of the Sarai Shahji village as a place for travellers to stay. Of the Delhi Metro Sadhana Enclave in Malviya Nagar. It is essentially Route 6 two Mughal buildings, the fi rst is a rectangular building with a large a small pavilion structure and gets its name from Civil Ho Ho Bus Route courtyard in the centre that houses several graves. Towards the west, is the tiny dome, carved out of solid stone and Lines a three-bay dalan (colonnaded verandah) with pyramidal roofs, which placed at its very top, that has the appearance of Heritage Route was once a mosque. a half-sliced melon. It is believed that Sheikh The other building is a slightly more elaborate apartment in the Kabir-ud-din Auliya, buried in the Lal form of a tower. The single room is entered through a set of three Gumbad spent his days under this doorways set within a large arch. The noticeable feature here is a dome and the night in the cave located SHAHJAHANABAD Red Fort balcony-like projection over the doorway which is supported by below it. The building has been dated carved red sandstone brackets. -

Surajkund Crafts a REAL MAKEOVER Kundli, Sonipat & Panipat: IDEAL

pg.14 A Times of India Presentation, DELHI, AUGUST 31, 2013 TIMES PROPERTY emergingtroika [FAST FACT] Kundli’s property market offers several options in residential and commercial properties I THE 135KM-LONG KMP EXPRESSWAY IN THE VICINITY IS NEARING COMPLETION AND WILL PROVIDE FASTER ACCESS TO THE IGI AIRPORT AND FACILITATE THE DEVELOPMENT OF A NEW COMMERCIAL CORRIDOR IN THE REGION Kundli,Kundli, SonipatSonipat && Panipat:Panipat: IDEALIDEAL INVESTMENTINVESTMENT QUICK BITES DESTINATIONDESTINATION QQ THE KUNDLI- MANESAR- PALWAL (KMP) EXPRESSWAY (ALSO KNOWN AS THE WESTERN Developers and investors are eyeing the Kundli, Sonipat, and Panipat belt as the rates here are still low, compared to the other parts of the PERIPHERAL EXPRESSWAY) NCR, and there is tremendous scope for appreciation and high returns on investment. A K TIWARY writes WHICH INTER- CONNECTS FOUR eveloping zones like ment, architecture, engineering, law, tele- crative investment opportunities with sev- shopping complexes, SCO's and commer- and recreational zones. Around 120 fami- HIGHWAYS— NH-1, NH-2, NH- Kundli, Sonipat, and Pa- com, medical, insurance and biotechnolo- eral options in residential and commer- cial spaces of various sizes to cater to the lies have moved in with another 300 ex- 8, AND NH-10 IN nipat are offering good gy. In the first phase, the education city cial properties. The area is adjacent to the entertainment and shopping needs of the pected in the next six months since Omaxe HARYANA—IS options for residential, would have the extended campuses of IIT- forthcoming KGP and KMP expressways. residents. Major brands like Bikanerwala, offered possession of villas and flats, a NEARING COMPLETION commercial, and indus- Delhi, National Law University, Bharti Apart from sale, many commercial and Mahal, Café Oz, Federal Bank, Mahin- company spokesman said. -

Delhi PEC As on 23 March 2015

SNO Centre Summary Contact Person Mobile No. A-387, Dilkhush Industrial Area, , Next To Vardhaman Plaza, G 1 T Karnal Road, Azadpur, Delhi, Model Town, North West Delhi, Satender Kumar 8595163978 Delhi - 110033 802 Second Floor, Arjun Ngar, Main Road, Kotla Mubarkpur, 2 Lovely Jain 43743101 Central Delhi, Madhya Pradesh - 110003 Shop No-28 Ist Floor, Deep Cinema Building, Adjacent To 3 Ashok Vihar Police Station, Ashok Vihar, North West Delhi, Hemant Sharma 40754707 Delhi - 110052 206, Suneja Tower-1, District Center, Janak Puri, West Delhi, 4 SHIV NARAYAN 45753900 Madhya Pradesh - 110058 S-606, Shakti Bhawan, School Block, Shakarpur, East Delhi, 5 Shiv Kumar 8447238328 Delhi - 110092 59 MM Road, Empire Business Centre, 2nd Floor, Rani Jhansi 6 Rais Ahmed 23529582 Marg, Jhandewalan, New Delhi, New Delhi, Delhi - 110055 LGF-133 World Trade Centre, Barakhamba Lane, Connaught 7 Ms. Poonam Wason 23414503 Place New Delhi, New Delhi, New Delhi, Delhi - 110001 Aadhaar Kendra, Near Mangla Puri Sabzi Mandi, F-82/3, 8 Solonki Chowk, Sadha Nagar, Palam, Palam Colony, South Ajay Kumar Kaushik 9868837335 West Delhi, Delhi - 110045 VEER BAZAR WALI GALI, FUN N FOOD, PLOY NO 1378, 9 KAPASHERA, Vasant VIHAR, South West Delhi, Delhi - HELP LINE 8130939998 110037 AADHAAR KENDRA, 691/2, KABOOL NAGAR,SHAHDRA, 10 HELP LINE 8130939998 Shahdara, North East Delhi, Delhi - 110032 Aadhaar Kendra, Near Pragati Maidan Metro Station, UIDAI 11 Regional Office Ground Floor, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Helpline 9953148006 Central Delhi, Delhi - 110001 AADHAR KENDRA, E-SR, E-SR, ALIPUR, Narela, North West 12 MOHIT WADHAWAN 9958112598 Delhi, Delhi - 110036 Shop No. -

Ammaliante Delhi Splendori E Miserie Della Capitale Indiana, Tra Vestigia Imperiali, Architetture

GreatBeauty I PALAZZI DEL POTERE Il seicentesco Lal Qila, il Forte Rosso di Old Delhi, gloria dell’epoca Moghul, è oggi patrimonio Unesco. Lal Qila, the seventeenth-century Red Fort of Old Delhi, glorious building from the Mughal era, is today included in the UNESCO Heritage list. Ammaliante Delhi Splendori e miserie della capitale indiana, tra vestigia imperiali, architetture coloniali e ambizioni future GETTY IMAGES Testo di Ilaria Simeone 86 _ ULISSE _ ottobre 2018 ULISSE _ ottobre 2018 _ 87 GreatBeauty CERCHI CONCENTRICI Connaught Place, a destra, capolavoro dell’architettura coloniale 340 inglese, è l’anima di New Delhi. Connaught Place, on right, a masterpiece sono le stanze del of British colonial architecture, Palazzo presidenziale is the soul of New Delhi. Rashtrapati Bhavan, nei cui giardini un tempo lavoravano 418 giardinieri. ahendra Pawar di- il bucato, uomini con il turbante gio- 340 are the rooms of the pinge l’intonaco cano a carte bevendo tè, le bancarelle Rashtrapati Bjavan, the presidential Palace. In con antiche fortezze di tessuti e monili si contendono lo the past, 418 gardeners M abbandonate, Rake- spazio con le botteghe dei barbieri e were employed for the sh Kumar Memrot i venditori di cibo da strada. Chandni garden’s maintenance. lo colora con fi gure Chowk s’arrampica fi no a un colosso dell’arte tribale, men- di arenaria rossa circondato per due tre Kajal Singh lo fa fi orire di segni chilometri dalle mura: è il seicentesco astratti e anonime mani lo rendono Lal Qila, il Forte Rosso, gloria dell’e- vivo con il volto del Mahatma Gan- poca Moghul e oggi Patrimonio Une- 3 dhi. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

LIST of ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No

LIST OF ORDINARY MEMBERS S.No. MemNo MName Address City_Location State PIN PhoneMob F - 42 , PREET VIHAR 1 A000010 VISHWA NATH AGGARWAL VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 98100117950 2 A000032 AKASH LAL 1196, Sector-A, Pocket-B, VASANT KUNJ NEW DELHI 110070 9350872150 3 A000063 SATYA PARKASH ARORA 43, SIDDHARTA ENCLAVE MAHARANI BAGH NEW DELHI 110014 9810805137 4 A000066 AKHTIARI LAL S-435 FIRST FLOOR G K-II NEW DELHI 110048 9811046862 5 A000082 P.N. ARORA W-71 GREATER KAILASH-II NEW DELHI 110048 9810045651 6 A000088 RAMESH C. ANAND ANAND BHAWAN 5/20 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI 110008 9811031076 7 A000098 PRAMOD ARORA A-12/2, 2ND FLOOR, RANA PRATAP BAGH DELHI 110007 9810015876 8 A000101 AMRIK SINGH A-99, BEHIND LAXMI BAI COLLEGE ASHOK VIHAR-III NEW DELHI 110052 9811066073 9 A000102 DHAN RAJ ARORA M/S D.R. ARORA & C0, 19-A ANSARI ROAD NEW DELHI 110002 9313592494 10 A000108 TARLOK SINGH ANAND C-21, SOUTH EXTENSION, PART II NEW DELHI 110049 9811093380 11 A000112 NARINDERJIT SINGH ANAND WZ-111 A, IInd FLOOR,GALI NO. 5 SHIV NAGAR NEW DELHI 110058 9899829719 12 A000118 VIJAY KUMAR AGGARWAL 2, CHURCH ROAD DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 13 A000122 ARUN KUMAR C-49, SECTOR-41 GAUTAM BUDH NAGAR NOIDA 201301 9873097311 14 A000123 RAMESH CHAND AGGARWAL B-306, NEW FRIENDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110025 989178293 15 A000126 ARVIND KISHORE 86 GOLF LINKS NEW DELHI 110003 9810418755 16 A000127 BHARAT KUMR AHLUWALIA B-136 SWASTHYA VIHAR, VIKAS MARG DELHI 110092 9818830138 17 A000132 MONA AGGARWAL 2 - CHURCH ROAD, DELHI CANTONMENT NEW DELHI 110010 9818331115 18 A000133 SUSHIL KUMAR AJMANI F-76 KIRTI NAGAR NEW DELHI 110015 9810128527 19 A000140 PRADIP KUMAR AGGARWAL DISCO COMPOUND, G.T.