Popular Images of Bankers Re'ected in Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audition Packet Anything Goes

Audition Packet – Mary Poppins Jr – Twelve Corners Middle School Auditions for Twelve Corners Middle School’s production of “Mary Poppins Jr” are Monday March 5, 3-4:30pm OR Tuesday March 6, 3-4:30pm in the TCMS Small Gym. You should ONLY ATTEND ONE DAY. Callbacks, if needed, will be Friday March 9, 3-4:30pm. You will receive an email if you are needed at callbacks. At the auditions you will be asked to: • Read one scene from the audition packet • Sing a song segment from the audition packet. If you are interested in a character who has a solo in the show, you will be asked to sing by yourself. If you do not want a solo, you can sing in a group of people. • Perform a short dance number in a group. Script and song selections for auditions can be found in this packet. Please look over all the scenes and the music. Have your parents and friends help you! Read through the scenes several times before the audition. YOU MUST HAVE A COMPLETED AUDITION FORM WHEN YOU ARRIVE AT AUDITIONS. Tracks for rehearsal can be downloaded from Dropbox using the addresses below. Note you do not need a DropBox account to download these. Vocal Tracks: https://goo.gl/LXXFDC Non-Vocal Tracks: https://goo.gl/Dop9oV (note that case matters, type it in exactly!) If you have questions, please call John Barthelmes (Director) at 585-305-4767 or email [email protected]. ==================================================================================================== Rehearsals, Performances Rehearsals will generally be: Mondays 3-5pm, Tuesdays 3-5pm, Thursdays 3-5pm, Fridays 3-5pm. -

Mary Poppins Jr. Full Synopsis from Mtishows.Com

Mary Poppins Jr. Full Synopsis From mtishows.com Bert, a man of many trades, introduces the audience to the unhappy Banks family: father George, mother Winifred, and children Jane and Michael (Prologue). The family; the housekeeper, Mrs. Brill; and the houseboy, Robertson Ay, are shocked when Katie Nanna quits and storms out in frustration. George muses about what he expects from the household - the nanny, in particular ("Cherry Tree Lane - Part 1"). Though Jane and Michael insist upon their own requirements for their caregiver ("The Perfect Nanny"), George dismisses their requests ("Cherry Tree Lane - Part 2"). As if summoned, Mary Poppins appears, offering her services as a nanny. She fits the children's requirements exactly ("Practically Perfect / Practically Perfect - Playoff" ). She then takes the children to the park, where they meet Bert, who describes how wonderful everyday life can be when spending time with Mary ("Jolly Holiday"). At first, the children are not convinced, but when Mary Poppins brings to life a park statue named Neleus, Jane and Michael are in awe of her. The children return home and gush to their father about the nanny, but George is preoccupied ("Winds Do Change"). A few weeks later, the household is preparing for Winifred's party, and Jane and Michael make a mess of the house. Despite Mary's magic ("A Spoonful of Sugar"), the party is ruined when no one attends ("Spoonful - Playoff"). Later, Mary takes the children on a visit to George's workplace, the bank ("Precision and Order - Part 1"). While Clerks are bustling about and clients are trying to convince George to grant them loans, the children burst into the bank ("Precision and Order - Part 2"). -

Mary Poppins JR Character Descriptions.P

Disney and Cameron Mackintosh’s Mary Poppins JR CHARACTER BREAKDOWN MALES Bert, the narrator of the story, is a good friend to Mary Poppins. An everyman, Bert is a chimney sweep and a sidewalk artist, among many other occupations. With a twinkle in his eye and skip in his step, Bert watches over the children and the goings-on around Cherry Tree Lane. He is a song-and-dance man with oodles of charm who is wise beyond his years. We are looking for a very strong singer, dancer and actor for this role. Songs: Prologue Practically Perfect (Playoff) Jolly Holiday Winds Do Change Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Twists and Turns Playing the Game/Chim Chim Cher-ee Let’s Go Fly a Kite Step in Time Step in Time (Playoff) A Spoonful of Sugar (Reprise) George Banks, husband to Winifred and father to Jane and Michael, is a banker to the very fiber of his being. Demanding “precision and order” in his household, he is a pipe-and-slippers man who doesn’t have much to do with his children, and believes that Miss Andrew, his cruel, strict, childhood nanny, gave him the perfect upbringing. George’s emotional armor, however off-putting, conceals a sensitive soul. A baritone (lower singer), George may also speak-sing and should be a very strong actor. Songs: Cherry Tree Lane (Part 1) Cherry Tree Lane (Part 2) Precision and Order (speaking) A Man Has Dreams Cherry Tree Lane (Reprise) Give Us the Word Anything Can Happen (Part 2) Anything Can Happen (Finale) Michael Banks is the cheeky son of Mr. -

“Mary Poppins Jr.” Scenes & Song

“Mary Poppins Jr.” Scenes & Song Scenes Songs ACT ONE Scene/Setting Scene 1A PROLOGUE Pgs. 1-3 #1“Prologue” Chimney Sweeps CAST: CS, B, GB,WB, J+M Scene 1B Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 4-12 #2 “Cherry Tree Lane”(Part 1) #3 “The Perfect Nanny” #4 “Cherry Tree Lane”(Part 2) CAST: KN, MB, RA, GB,WB, J+M, MP Scene 2 Cherry Tree Lane, Nursery Pgs. 13-18 #8 “Practically Perfect” CAST: J+M, MP Scene 3 PARK w/Statues Pgs. 19-29 #9 “Practically Perfect”(Playoff) #10 “Jolly Holiday” #11 “But How?” CAST: CS, B, J+M, MP, N & S, Park Strollers Scene 4A Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 30-31 CAST: GB,WB, J+M, MP Scene 4B Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pg. 32 #12 “Winds Do Change” CAST : B Scene 4C Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 33-35 CAST: MB, RA, WB, J+M, MP Scene 4D Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 36-41 #13“A Spoonful of Sugar” CAST: MB, RA, WB, J+M, MP, Bees Scene 4E Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pg. 41 #14“Spoonful Playoff” CAST: MB, WB Scene 5A Inside the Bank Pgs. 42-45 #15 “Precision and Order” (Part 1) #16 “Precision and Order” (Part 2) CAST: J+M, MP, GB, Mr. O, MS, Clerks, VH Scene 5B Inside the Bank Pgs. 45-48 #16 “Precision and Order” (Part 2) #17 “Precision and Order” (Part 3) CAST: J+M, MP, GB, NB Scene 5C Inside the Bank Pg. 48-49 #18 “A Man Has Dreams” CAST: GB, NB Scene 6 Outside the Cathedral Pgs. -

MP Program V4

Directed by Mark Edwards Scenic design: Jeremy Woods | Music: Ellen Shuler Choreography: Cynthia Collins Cast Mary Poppins.............................................................................Ellie Leverett Bert.....................................................................................Charles Cushman Mrs. Brill...................................................................................Ella Villeneuve George Banks...................................................................Andrew Bechthold Winifred Banks......................................................................Lauren Glusman Birdwoman.........................................................................................Lexi Lee Katie Nanna.......................................................................Scanlon Mellowes Jane...................................................................................Anna Fitzsimmons Michael...................................................................................Kush Daruwala Policeman.................................................................................Henry Osberg Miss Lark..............................................................................Gabrielle Fellenz Admiral Boom.................................................................................Wali Amin Robertson Ay................................................................................Liam Grady Park Keeper.................................................................................Henry Stone Neleus..................................................................................Tyler -

Mary Poppins Program

The Aerospace Players’ production of Disney & Cameron Mackintosh’s A Musical based on the stories of P. L. Travers and the Walt Disney Film Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman Book by Julian Fellowes New Songs and Additional Music and Lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe Co-Created by Cameron Mackintosh James Armstrong Theatre Torrance, California July 20-22 & 26-28, 2018 Flying by Foy Concessions Snacks and beverages are available in the lobby at intermission. 50/50 Drawing The winner receives 50% of the money collected at each performance. The winning number will be posted in the lobby at the end of each performance. Actor/Orchestra-Grams: $1 each “Wish them Luck for only a Buck” All proceeds support The Aerospace Players’ production costs – Enjoy the Show! Director’s Note On behalf of our cast and crew, I’m very excited to welcome you to The Aerospace Players’ production of Mary Poppins! The cast has been in rehearsals for almost three months now, and is thrilled to bring the show to stage, and to share it with you. Mary Poppins, despite the popularity of the 1964 movie, is only a relatively recent arrival to stage, having made its stage debut in London in 2004, then opening on Broadway in 2006, where it ran for 2,619 performances over seven years. Featuring the classic music and characters of the movie, it nonetheless reinvented and deepened the story of the Banks family, adding interesting new characters and heartfelt new music. And since no one could imagine Mary Poppins without a little “magic,” it also seems includes some special treats for the audience. -

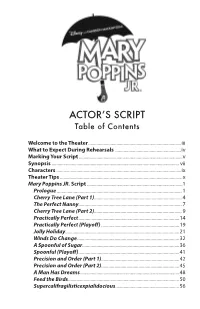

Actor's Script

ACTOR’S SCRIPT Table of Contents Welcome to the Theater ...............................................................................iii What to Expect During Rehearsals ........................................................iv Marking Your Script ........................................................................................v Synopsis ............................................................................................................ vii Characters ..........................................................................................................ix Theater Tips ........................................................................................................x Mary Poppins JR. Script .................................................................................1 Prologue ........................................................................................................1 Cherry Tree Lane (Part 1) .........................................................................4 The Perfect Nanny ......................................................................................7 Cherry Tree Lane (Part 2) .........................................................................9 Practically Perfect ....................................................................................14 Practically Perfect (Playoff) .................................................................19 Jolly Holiday ...............................................................................................21 Winds Do Change -

Study Guide ORIGINAL MUSIC and LYRICS by RICHARD M

©Disney/CML A MUSICAL BASED ON THE STORIES OF P.L. TRAVERS AND THE WALT DISNEY FILM study guide ORIGINAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD M. SHERMAN AND ROBERT B. SHERMAN Prepared by Disney Theatrical group Education Department BOOK BY JULIAN FELLOWES NEW SONGS AND ADDITIONAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY GEORGE STILES AND ANTHONY DREWE CO-CREATED BY CAMERON MACKINTOSH intro - welcome Anything can happen if we recognize In Mary Poppins, the factory owner John Northbrook tells Michael that money has a worth (for example, one dollar or, in London, one the magic of everyday life. Author P.L. Travers pound) but it also has a value (or what the money can do to help understood this special kind of magic when she published her first others). Mary Poppins teaches the Banks family (and the audience!) book, Mary Poppins, in 1934. The tale of the mysterious nanny who to value the important things in life: family, friendship and teaches a troubled family to appreciate the important things in life imagination. In Mary Poppins, Mary sings, Anything can happen if went on to become one of the most recognized and beloved stories you let it. Mary Poppins is about discovering the extraordinary world of all time. Thirty years later, Walt Disney released the film based around us, even when things look bleak. This guide is designed to on Travers' stories: a unique mixture of animation and live action help you explore the extraordinary world of Mary Poppins. that has become a classic. Now Mary Poppins flies over audiences and lands on a Disney BROADEN YOUR HORIZON Broadway stage, complete with new songs and breathtaking theatrical magic. -

Dec. 11, 2014 ***** MARY POPPINS ***** V10. 6 CAST Mary Poppins Bert Mr

Dec. 11, 2014 ***** MARY POPPINS ***** v10. 6 CAST Mary Poppins Bert Mr. George Banks Mrs. Winifred Banks Jane Banks Michael Banks Ellen: Maid Mrs. Brill: Cook Katie Nanna, Nannies Constable Jones Admiral Boom & Mates Uncle Albert The Bird Woman Mr. Dawes, Sr. & Bankers: Mr. Dawes, Jr.; Mr. Grubbs; Mr. Tomes Penguin Waiters & Animals (1520); Supercal band (6): 1 scene Chimneysweeps (2025): 1 scene London Choir (13): on floor and 1 number on stage Lullaby Chorus: 68 Girls: Stay Awake; Feed the Birds SCENES SCENE 1: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: Sister, The Life I Lead, Advertisement SCENE 2: Next Morning: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: The Interview SCENE 3: Nursery: Spoonful SCENE 4: In the Park SCENE 5: Jolly Holiday: Penguin Dance, Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious SCENE 6: Nursery: Stay Awake SCENE 7: Next Morning: Out of Sorts SCENE 8: Uncle Albert SCENE 9: Parlor: A British Bank SCENE 10: Nursery: Feed the Birds SCENE 11: The Bank: Fidelity Fiduciary Bank SCENE 12: Chimney Sweeps: Chimchimeree, Step in Time SCENE 13: Parlor: That Poppins Woman: A Man Has Dreams SCENE 14: The Bank: Sacked SCENE 15: Parlor & Street: Go Fly a Kite MUSICAL NUMBERS All songs written and composed by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman. Mary Poppins (Original Soundtrack) No. Title Performer(s) Length 1. "Overture" (Instrumental) 3:01 2. "Sister Suffragette" Mrs Banks/Maids 1:45 3. "The Life I Lead" Mr Banks 2:01 4. "The Perfect Nanny" Jane & Michael 1:39 5. "A Spoonful of Sugar" Mary P 4:09 1 of 53 Dec. 11, 2014 7. -

Mary Poppins Characters and Synopsis.Pdf

Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman Book by Julian Fellowes New Songs and Additional Music and Lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe Co-Created by Cameron Mackintosh A Musical based on the stories of P.L. Travers and the Walt Disney Film Character List CHARACTERS: DESCRIPTIONS: (ages listed are suggested character age, not actor age) ENSEMBLE MARY POPPINS features a large ensemble of singers and dancers in a variety of supporting roles. MARY POPPINS includes a number of dance styles, including tap, ballet, jazz and other genres. Ensemble roles may not be needed at call-backs. ENSEMBLE ROLES INCLUDE: ANNIE, FANNIE, VALENTINE, TEDDY BEAR, MR. PUNCH, DOLL, TOYS, CHIMNEY SWEEPS, PARKGOERS, MISS SMYTHE, VON HUBBLER, NORTHBROOK, POLICEMAN, BANK EMPLOYEES BERT Bert is a Chimney Sweep and Jack-of-all-Trades. Charming and charismatic. Must move well. Late 20s to mid 30s. Baritone to G. Callback Music: Let’s Go Fly a Kite, Chim-Chiminey & Jolly Holiday MARY POPPINS Jane and Michael’s Nanny, Mary Poppins is a dazzling personality and a force to be reckoned with. Mid 20s. Mezzo Soprano with a strong top. Callback Music: Practically Perfect & Jolly Holiday MR. GEORGE BANKS A bank manager, Mr. Banks is father to Jane and Michael. He tries to be a good provider, but often forgets how to be a good father. Late 30s to Early 40s, Baritone. Callback Music: Precision and Order & Good for Nothing MRS. WINIFRED BANKS A former actress, Mrs. Banks is very busy trying to live up to her husband’s expectations. -

You Have Been Asked to Participate in a Callback Audition for SFE's Winter

October 23, 2019 Dear , Congratulations! You have been asked to participate in a callback audition for SFE’s Winter Musical—Mary Poppins, Jr. As stated in the information packet, callback auditions will be held on Thursday, October 24 from 4:00pm-6:00pm on the stage. You must stay for the entire time. In order to prepare for this callback, you will be asked to learn new speaking lines and songs. The new speaking lines and songs do not have to be memorized, but do come prepared and practiced. Callbacks are performed in front of and with all callback auditionees. Though you might not get to sing every song provided, or speak every line provided, please have ALL of the following materials practiced and ready for performance on the stage: FEMALES: NEW song: “Practically Perfect”- Mary Poppins—memorized or learned NEW song: “Brimstone & Treacle”- Miss Andrew—memorized or learned NEW Selection #1: Jane & Michael—memorized or learned NEW Selection #2: Mary Poppins, Jane, Mrs. Corry—memorized or learned NEW Selection #3: Northbrook—memorized or learned NEW Selection #4: Winifred, Miss Andrew, Mrs. Brill, Jane—memorized or learned NEW Selection #5: Winifred, Mrs. Brill—memorized or learned MALES: NEW song: “A Man Has Dreams”- George—memorized or learned NEW song: “Jolly Holiday”- Michael—memorized or learned NEW Selection #1: Bert & Michael—memorized or learned NEW Selection #2: Bert & Michael—memorized or learned NEW Selection #3: Von Hussler, George, Northbrook—memorized or learned NEW Selection #4: Michael—memorized or learned NEW Selection #5: Robertson Ay—memorized or learned Please practice this material and come as prepared as possible! Remember, the more you practice, the stronger your callback will be. -

Mary Poppins *****

***** MARY POPPINS ***** CAST Mary Poppins Bert Mr. George Banks Mrs. Winifred Banks Jane Banks Michael Banks Ellen: Maid Mrs. Brill: Cook Katie Nanna, Nannies Constable Jones Admiral Boom & Mates Uncle Arthur The Bird Woman Mr. Dawes, Sr. & Bankers: Mr. Dawes, Jr.; Mr. Grubbs; Mr. Tomes Penguin Waiters & Animals (15-20); Supercal band (6): 1 scene Chimneysweeps (20-25): 1 scene London Choir (20-30): on floor and 1 number on stage Lullaby Chorus: 6-8 Girls: Stay Awake; Feed the Birds SCENES SCENE 1: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: Sister, The Life I Lead, Advertisement ................. 2 SCENE 2: Next Morning: 17 Cherry Tree Lane: The Interview .............................. 11 SCENE 3: Nursery: Spoonful ................................................................................... 14 SCENE 4: In the Park ............................................................................................... 17 SCENE 5: Jolly Holiday: Supercal ........................................................................... 19 SCENE 6: Nursery: Stay Awake .............................................................................. 23 SCENE 7: Next Morning: Out of Sorts .................................................................... 25 SCENE 8: Uncle Arthur ............................................................................................ 27 SCENE 9: Parlor: A British Bank ............................................................................. 30 SCENE 10: Nursery: Feed the Birds .......................................................................