'CIVIL-BASED' LUNAR CALENDAR Rolf Krauss the Days of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moons Phases and Tides

Moon’s Phases and Tides Moon Phases Half of the Moon is always lit up by the sun. As the Moon orbits the Earth, we see different parts of the lighted area. From Earth, the lit portion we see of the moon waxes (grows) and wanes (shrinks). The revolution of the Moon around the Earth makes the Moon look as if it is changing shape in the sky The Moon passes through four major shapes during a cycle that repeats itself every 29.5 days. The phases always follow one another in the same order: New moon Waxing Crescent First quarter Waxing Gibbous Full moon Waning Gibbous Third (last) Quarter Waning Crescent • IF LIT FROM THE RIGHT, IT IS WAXING OR GROWING • IF DARKENING FROM THE RIGHT, IT IS WANING (SHRINKING) Tides • The Moon's gravitational pull on the Earth cause the seas and oceans to rise and fall in an endless cycle of low and high tides. • Much of the Earth's shoreline life depends on the tides. – Crabs, starfish, mussels, barnacles, etc. – Tides caused by the Moon • The Earth's tides are caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon. • The Earth bulges slightly both toward and away from the Moon. -As the Earth rotates daily, the bulges move across the Earth. • The moon pulls strongly on the water on the side of Earth closest to the moon, causing the water to bulge. • It also pulls less strongly on Earth and on the water on the far side of Earth, which results in tides. What causes tides? • Tides are the rise and fall of ocean water. -

The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars

Heavenly Mathematics: The Mathematics of the Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Gregorian Calendars Helmer Aslaksen Department of Mathematics National University of Singapore [email protected] www.math.nus.edu.sg/aslaksen/ www.chinesecalendar.net 1 Public Holidays There are 11 public holidays in Singapore. Three of them are secular. 1. New Year’s Day 2. Labour Day 3. National Day The remaining eight cultural, racial or reli- gious holidays consist of two Chinese, two Muslim, two Indian and two Christian. 2 Cultural, Racial or Religious Holidays 1. Chinese New Year and day after 2. Good Friday 3. Vesak Day 4. Deepavali 5. Christmas Day 6. Hari Raya Puasa 7. Hari Raya Haji Listed in order, except for the Muslim hol- idays, which can occur anytime during the year. Christmas Day falls on a fixed date, but all the others move. 3 A Quick Course in Astronomy The Earth revolves counterclockwise around the Sun in an elliptical orbit. The Earth ro- tates counterclockwise around an axis that is tilted 23.5 degrees. March equinox June December solstice solstice September equinox E E N S N S W W June equi Dec June equi Dec sol sol sol sol Beijing Singapore In the northern hemisphere, the day will be longest at the June solstice and shortest at the December solstice. At the two equinoxes day and night will be equally long. The equi- noxes and solstices are called the seasonal markers. 4 The Year The tropical year (or solar year) is the time from one March equinox to the next. The mean value is 365.2422 days. -

Phases of the Moon by Patti Hutchison

Phases of the Moon By Patti Hutchison 1 Was there a full moon last night? Some people believe that a full moon affects people's behavior. Whether that is true or not, the moon does go through phases. What causes the moon to appear differently throughout the month? 2 You know that the moon does not give off its own light. When we see the moon shining at night, we are actually seeing a reflection of the Sun's light. The part of the moon that we see shining (lunar phase) depends on the positions of the sun, moon, and the earth. 3 When the moon is between the earth and the sun, we can't see it. The sunlit side of the moon is facing away from us. The dark side is facing toward us. This phase is called the new moon. 4 As the moon moves along its orbit, the amount of reflected light we see increases. This is called waxing. At first, there is a waxing crescent. The moon looks like a fingernail in the sky. We only see a slice of it. 5 When it looks like half the moon is lighted, it is called the first quarter. Sounds confusing, doesn't it? The quarter moon doesn't refer to the shape of the moon. It is a point of time in the lunar month. There are four main phases to the lunar cycle. Four parts- four quarters. For each of these four phases, the moon has orbited one quarter of the way around the earth. -

The Determination of Longitude in Landsurveying.” by ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc

316 DOWNES ON LONGITUDE IN LAXD SUIWETISG. [Selected (Paper No. 3027.) The Determination of Longitude in LandSurveying.” By ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc. M. Inst. C.E. THISPaper is presented as a sequel tothe Author’s former communication on “Practical Astronomy as applied inLand Surveying.”’ It is not generally possible for a surveyor in the field to obtain accurate determinationsof longitude unless furnished with more powerful instruments than is usually the case, except in geodetic camps; still, by the methods here given, he may with care obtain results near the truth, the error being only instrumental. There are threesuch methods for obtaining longitudes. Method 1. By Telrgrcrph or by Chronometer.-In either case it is necessary to obtain the truemean time of the place with accuracy, by means of an observation of the sun or z star; then, if fitted with a field telegraph connected with some knownlongitude, the true mean time of that place is obtained by telegraph and carefully compared withthe observed true mean time atthe observer’s place, andthe difference between thesetimes is the difference of longitude required. With a reliable chronometer set totrue Greenwich mean time, or that of anyother known observatory, the difference between the times of the place and the time of the chronometer must be noted, when the difference of longitude is directly deduced. Thisis the simplest method where a camp is furnisl~ed with eitherof these appliances, which is comparatively rarely the case. Method 2. By Lunar Distances.-This observation is one requiring great care, accurately adjusted instruments, and some littleskill to obtain good results;and the calculations are somewhat laborious. -

Understanding and Observing the Moon's Phases and Eclipses

Because of the Moon’s trek around the sky, from time to time it passes near or even Understanding drifts over other celestial objects. Close approaches are known as conjunctions , whereas covering another object is called an occultation and Observing or eclipse, depending on whether a night time object or the Sun is covered. Tight groupings of the Moon with bright planets or stars are striking sights and make excellent photographs, particularly if a scenic The Moon, earthly foreground is included. Use a camera tripod to make sure your camera stays steady during the time exposure. Depending on your choice of camera, exposures of about ¼ its Phases to a few seconds should give useable results. Don’t forget to experiment with subtle foreground lighting for dramatic effects. and Lunar Phases Eclipses A common misconception is that lunar phases are somehow caused by the shadow of the Earth falling onto the Moon. In The Moon is Earth’s closest companion in reality, the Moon’s phases are the result of space. Though well studied, to many people, our changing viewing angle of the Moon as it Earth’s rocky ‘sibling’ represents an orbits the Earth. unknown entity. This brochure will become apparent in the evening sky shortly About 7 days after New Moon, the shadow introduce you to lunar phases and motions Understanding the Moon’s phases cannot after sunset. Because the Moon is now line separating the lit as well as explain the basics of eclipses. really be done without also understanding surrounded by darker sky, the faintly and unlit portions of how the Moon’s position in the sky varies luminous shaded part of the Moon (known as Lunar Motions throughout the lunar month. -

The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the Concept of Adhik-Maas

Volume -3, Issue-3, July 2013 The Indian Luni-Solar Calendar and the giving rise to alternative periods of light and darkness. All human and animal life has evolved accordingly, Concept of Adhik-Maas (Extra-Month) keeping awake during the day-light but sleeping through the dark nights. Even plants follow a daily rhythm. Of Introduction: course some crafty beings have turned nocturnal to take The Hindu calendar is basically a lunar calendar and is advantage of the darkness, e.g., the beasts of prey, blood– based on the cycles of the Moon. In a purely lunar sucker mosquitoes, thieves and burglars, and of course calendar - like the Islamic calendar - months move astronomers. forward by about 11 days every solar year. But the Hindu calendar, which is actually luni-solar, tries to fit together The next natural clock in terms of importance is the the cycle of lunar months and the solar year in a single revolution of the Earth around the Sun. Early humans framework, by adding adhik-maas every 2-3 years. The noticed that over a certain period of time, the seasons concept of Adhik-Maas is unique to the traditional Hindu changed, following a fixed pattern. Near the tropics - for lunar calendars. For example, in 2012 calendar, there instance, over most of India - the hot summer gives way were 13 months with an Adhik-Maas falling between to rain, which in turn is followed by a cool winter. th th August 18 and September 16 . Further away from the equator, there were four distinct seasons - spring, summer, autumn, winter. -

Lunar Sourcebook : a User's Guide to the Moon

3 THE LUNAR ENVIRONMENT David Vaniman, Robert Reedy, Grant Heiken, Gary Olhoeft, and Wendell Mendell 3.1. EARTH AND MOON COMPARED fluctuations, low gravity, and the virtual absence of any atmosphere. Other environmental factors are not The differences between the Earth and Moon so evident. Of these the most important is ionizing appear clearly in comparisons of their physical radiation, and much of this chapter is devoted to the characteristics (Table 3.1). The Moon is indeed an details of solar and cosmic radiation that constantly alien environment. While these differences may bombard the Moon. Of lesser importance, but appear to be of only academic interest, as a measure necessary to evaluate, are the hazards from of the Moon’s “abnormality,” it is important to keep in micrometeoroid bombardment, the nuisance of mind that some of the differences also provide unique electrostatically charged lunar dust, and alien lighting opportunities for using the lunar environment and its conditions without familiar visual clues. To introduce resources in future space exploration. these problems, it is appropriate to begin with a Despite these differences, there are strong bonds human viewpoint—the Apollo astronauts’ impressions between the Earth and Moon. Tidal resonance of environmental factors that govern the sensations of between Earth and Moon locks the Moon’s rotation working on the Moon. with one face (the “nearside”) always toward Earth, the other (the “farside”) always hidden from Earth. 3.2. THE ASTRONAUT EXPERIENCE The lunar farside is therefore totally shielded from the Earth’s electromagnetic noise and is—electro- Working within a self-contained spacesuit is a magnetically at least—probably the quietest location requirement for both survival and personal mobility in our part of the solar system. -

Lunar Motion Motion A

2 Lunar V. Lunar Motion Motion A. The Lunar Calendar Dr. Bill Pezzaglia B. Motion of Moon Updated 2012Oct30 C. Eclipses 3 1. Phases of Moon 4 A. The Lunar Calendar 1) Phases of the Moon 2) The Lunar Month 3) Calendars based on Moon b). Elongation Angle 5 b.2 Elongation Angle & Phase 6 Angle between moon and sun (measured eastward along ecliptic) Elongation Phase Configuration 0º New Conjunction 90º 1st Quarter Quadrature 180º Full Opposition 270º 3rd Quarter Quadrature 1 b.3 Elongation Angle & Phase 7 8 c). Aristarchus 275 BC Measures the elongation angle to be 87º when the moon is at first quarter. Using geometry he determines the sun is 19x further away than the moon. [Actually its 400x further !!] 9 Babylonians (3000 BC) note phases are 7 days apart 10 2. The Lunar Month They invent the 7 day “week” Start week on a) The “Week” “moon day” (Monday!) New Moon First Quarter b) Synodic Month (29.5 days) Time 0 Time 1 week c) Spring and Neap Tides Full Moon Third Quarter New Moon Time 2 weeks Time 3 weeks Time 4 weeks 11 b). Stone Circles 12 b). Synodic Month Stone circles often have 29 stones + 1 xtra one Full Moon to Full Moon off to side. Originally there were 30 “sarson The cycle of stone” in the outer ring of Stonehenge the Moon’s phases takes 29.53 days, or ~4 weeks Babylonians measure some months have 29 days (hollow), some have 30 (full). 2 13 c1). Tidal Forces 14 c). Tides This animation illustrates the origin of tidal forces. -

Free Lunar Phases Interactive Organizer

Free Lunar Phases Interactive Organizer Created by Gay Miller © Gay Miller Page 1 Lunar Phases MS-ESS1-1. Develop and use a model of the Earth-sun-moon system to describe the cyclic patterns of lunar phases, eclipses of the sun and moon, and seasons. This is a sample from Earth’s Place in the Universe Interactive Organizers The pattern and directions for creating the Lunar Phases organizer may be found on page 4 with the answer key on page 5. Notice that each flap lifts up so students can visualize how the moon would look from the angle of Earth. © Gay Miller Page 2 Lunar Phases Full Moon Day 15 Waning Gibbous Days 16-21 Waxing Gibbous Days 9-14 1st Quarter rd 3 Quarter Days 7-8 Day 22 Waning Crescent Waxing Crescent Days 23-28 Days 2-6 New Moon Days 1 & 29 s u n l i g h t Lunar Phases © Gay Miller Page 3 MS-ESS1-1 Instructions: 1) On each of the eight tabs, write the moon phase above the circle shape and the days this phase takes place in the lunar cycle under the circle shape. Using a black crayon, shade each circle so that it accurately shows the amount of the moon visible from Earth during its phase. 2) Cut out the organizer and glue the middle portion only onto your organizer notebook so that the tabs may be lifted up to view the moon. On your organizer notebook page, draw the sun and write a title for your page. © Gay Miller Page 4 Full Moon Day 15 Waning Gibbous Waxing Gibbous Days 16-21 Days 9-14 1 Day st Quarter 22 s 7 s Quarter - Day 8 rd 3 Waning Crescent Waxing Crescent Days 23-28 Days 2-6 New Moon Days 1 & 29 On this answer key words could not be typed onto the tabs without losing clarity. -

Phases of the Moon

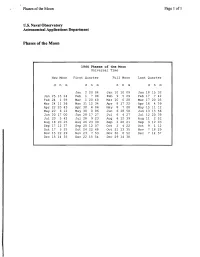

Phases ofthe Moon Page 1 of 1 u.s. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department Phases of the Moon 1944 Phases of the Moon Universal Time New Moon First Quarter Full Moon Last Quarter d h m d h m d h m d h m Jan 2 20 04 Jan 10 10 09 Jan 18 15 32 Jan 25 15 24 Feb 1 7 08 Feb 9 5 29 Feb 17 7 42 Feb 24 1 59 Mar 1 20 40 Mar 10 0 28 Mar 17 20 05 Mar 24 11 36 Mar 31 12 34 Apr 8 17 22 Apr 16 4 59 Apr 22 20 43 Apr 30 6 06 May 8 7 28 May 15 11 12 May 22 6 12 May 30 0 06 Jun 6 18 58 Jun 13 15 56 Jun 20 17 00 Jun 28 17 27 Jul 6 4 27 Jul 12 20 39 Jul 20 5 42 Jul 28 9 23 Aug 4 12 39 Aug 11 2 52 Aug 18 20 25 Aug 26 23 39 Sep 2 20 21 Sep 9 12 03 Sep 17 12 37 Sep 25 12 07 Oct 2 4 22 Oct 9 1 12 Oct 17 5 35 Oct 24 22 48 Oct 31 13 35 Nov 7 18 29 Nov 15 22 29 Nov 23 7 53 Nov 30 0 52 Dec 7 14 57 Dec 15 14 35 Dec 22 15 54 Dec 29 14 38 Phases ofthe Moon and Percent ofthe Moon Illuminated Page 1 of4 U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department Phases of the Moon and Percent of the Moon Illuminated Ac,",<OO'______________________________"',',,',', (For Moon phase information specific to a particular date, see Phases of the Moon or Complete Sun and Moon Data for One Day or fraction of the Moon ILLuminated in Data Services.) From any location on the Earth, the Moon appears to be a circular disk which, at any specific time, is illuminated to some degree by direct sunlight. -

Calendars from Around the World

Calendars from around the world Written by Alan Longstaff © National Maritime Museum 2005 - Contents - Introduction The astronomical basis of calendars Day Months Years Types of calendar Solar Lunar Luni-solar Sidereal Calendars in history Egypt Megalith culture Mesopotamia Ancient China Republican Rome Julian calendar Medieval Christian calendar Gregorian calendar Calendars today Gregorian Hebrew Islamic Indian Chinese Appendices Appendix 1 - Mean solar day Appendix 2 - Why the sidereal year is not the same length as the tropical year Appendix 3 - Factors affecting the visibility of the new crescent Moon Appendix 4 - Standstills Appendix 5 - Mean solar year - Introduction - All human societies have developed ways to determine the length of the year, when the year should begin, and how to divide the year into manageable units of time, such as months, weeks and days. Many systems for doing this – calendars – have been adopted throughout history. About 40 remain in use today. We cannot know when our ancestors first noted the cyclical events in the heavens that govern our sense of passing time. We have proof that Palaeolithic people thought about and recorded the astronomical cycles that give us our modern calendars. For example, a 30,000 year-old animal bone with gouged symbols resembling the phases of the Moon was discovered in France. It is difficult for many of us to imagine how much more important the cycles of the days, months and seasons must have been for people in the past than today. Most of us never experience the true darkness of night, notice the phases of the Moon or feel the full impact of the seasons. -

Lab Experiment

Lab 2 Observing the Sky 2.1 Introduction Early humans were fascinated by the order and harmony they observed in the celestial realm, the regular, predictable motions of Sun, Moon, planets, and “fixed” stars (organized into patterns called constellations). They watched stars rise in the east, their height (or altitude) above the horizon steadily increasing with each passing hour of the night. After they reached a high point, at culmination, they were observed to slowly set in the west. Other stars never rose or set, but rotated once a day around a fixed point in the sky (the celestial pole). The ancients recognized seven objects that moved slowly with respect to the fixed stars. These were the Sun, the Moon, and five bright planets (from the Greek word for “wandering star”). The Sun and Moon moved steadily eastward through a band of twelve constellations located above the Earth’s equator called the zodiac. As people spent a lot of time outdoors without artificial lighting, changes in the appearance of the Moon were obvious to them. They tracked the Moon’s phase (fractional illumination) from night to night, as it grew from new to full and back to new each month (or “moonth”). The Sun moves more slowly through the sky. Its journey once around the zodiac takes a full year, and its changing position heralds seasonal changes. The ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Mayans, Chinese and other civilizations designed calendars based on their ob- servations of the Sun and Moon, and carefully watched the skies. In New Mexico, ancient pueblo peoples used celestial patterns to determine when to plant crops in spring, when to prepare irrigation ditches for summer rains, and how to orient buildings to maximize solar heating in winter.