The Prudence of Avoiding a Constitutional Decision in Snyder V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sticks and Stones: IIED and Speech After Snyder V. Phelps

Missouri Law Review Volume 76 Issue 4 Fall 2011 Article 7 Fall 2011 Sticks and Stones: IIED and Speech after Snyder v. Phelps Heath Hooper Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Heath Hooper, Sticks and Stones: IIED and Speech after Snyder v. Phelps, 76 MO. L. REV. (2011) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol76/iss4/7 This Notes and Law Summaries is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hooper: Hooper: Sticks and Stones NOTE Sticks and Stones: IED and Speech After Snyder v. Phelps Snyder v. Phelps, 131 S. Ct. 1207 (2011). HEATH HOOPER* 1. INTRODUCTION On March 3, 2006, Marine Lance Corporal Matthew Snyder died while serving a tour of duty in Iraq.] After hearing of his funeral, members of the Kansas-based Westboro Baptist Church attended and protested the Maryland ceremony bearing graphic photos and signs declaring "Thank God for IEDs" and "Thank God for Dead Soldiers." 2 The church members did so in reflec- tion of their religious belief that God has doomed America and its military missions because of the country's tolerance for homosexuality. 3 Following the protest, Matthew Snyder's father, Albert Snyder, sued the Westboro Bap- tist Church for a variety of civil wrongs, including intentional infliction of emotional distress,4 thus setting up a conflict pitting free speech against tort liability that ultimately reached the United States Supreme Court. -

U.S. Supreme Court Holds First Amendment Shields Westboro Baptist Military Funeral Protesters from Tort Liability

LESBIAN/GAY LAW NOTES April 2011 49 U.S. SUPREME COURT HOLDS FIRST AMENDMENT SHIELDS WESTBORO BAPTIST MILITARY FUNERAL PROTESTERS FROM TORT LIABILITY A majority of the Supreme Court of the dismissed Snyder’s claims for defama- public matters was intended to mask an at- United States has held that members of tion and publicity given to private life, and tack on Snyder over a private matter.” Rob- the Westboro Baptist Church, who regu- held a trial on the remaining claims. A jury erts held that Westboro’s message “cannot larly protest military funerals holding found for Snyder on the remaining claims be restricted simply because it is upsetting signs bearing slogans expressing their dis- and held Westboro liable for $2.0 million or arouses contempt” and concluded that approval of America’s tolerance of homo- in compensatory damages and $8.0 mil- the jury verdict imposing tort liability on sexuality, such as “God Hates Fags,” “Fag lion in punitive damages; the trial court Westboro for intentional infliction of emo- Troops,” “Thank God for Dead Soldiers,” later remitted the punitive damages award tional distress must be set aside. and “America is Doomed,” was shielded by to $2.1 million. Westboro appealed to the Justice Roberts also rejected Snyder’s ar- the First Amendment from tort liability for 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, which held gument that he was “a member of a captive causing extreme emotional distress to the that Westboro was entirely shielded from audience at his son’s funeral,” stating that father of an Iraq war veteran when they liability by the First Amendment. -

Reader's Guide

South Dakota Humanities Council South Dakota Humanities Council Presents the Presents the South Dakota Humanities Council South Dakota Humanities Council South2020 Dakota ONEPresents Humanities BOOK the Council SD 2020 ONEPresents BOOK the SD 2020 ONEPresents BOOK the SD - READER’S2020 ONE BOOK GUIDE SD - TABLE of CONTENTS About the One Book SD Program & South Dakota Festival of Books . 1 About the 2020 One Book, Unfollow . 3 About the Author, Megan Phelps-Roper. 5 Introduction . 7 Discussion Questions . 11 Praise for the Book . .. 14 Thank You to Sponsors & Board . 16 About the One Book Program, South Dakota Festival of Books Contact [email protected] or call 605-688-6113 with any questions. Festival of Books: ‘Bringing Readers and Writers Together’ The 2020 Festival of Books will be held Oct. 2–4 in Brookings, featuring authors and illustrators participating in readings, lectures, workshops, panel discussions and book signings. South Dakota’s premier annual literary event, the Festival includes more than 40 exhibitors and draws more than 5,000 session attendees, with an additional 5,000 students meeting children’s/YA authors and illustrators. Most Festival events are free, but each year there are a handful of ticketed events that can be purchased on our website. Since its inception in 2003, the South Dakota Festival of Books has featured award-winning authors in all genres: fiction authors Jane Smiley, Louise Erdrich, William Kent Krueger, and Tim O’Brien; children’s authors Gene Luen Yang and Kate DiCamillo; non-fiction authors Timothy Egan and Denise Kiernan, and many more. The event is produced by the South Dakota Humanities Council, a statewide non-profit whose sole purpose is to provide humanities programs for South Dakotans. -

42 Kansas History Assembling a Buckle of the Bible Belt: from Enclave to Powerhouse by Jay M

Immanuel Baptist Church, with its towering cross, in downtown Wichita, Kansas. Courtesy of Jay M. Price. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 41 (Spring 2018): 42-61 42 Kansas History Assembling a Buckle of the Bible Belt: From Enclave to Powerhouse by Jay M. Price n Sunday, July 14, 1991, Bob Knight, mayor of Wichita, Kansas, had just delivered a talk at a local church when Chief of Police Rick Stone came up and warned him that “we’re going to have some very difficult circumstances tomorrow.” Operation Rescue, an antiabortion organization, intended to picket local abortion facilities. In particular, Operation Rescue leaders such as Randall Terry wanted to organize local and national antiabortion efforts to focus national attention on abortion providers such as George Tiller. Stone noted that “they’ll Oblock, they’ll protest, first of all, but they’ve been known to block entrances.” Knight responded that these actions “shouldn’t be insurmountable to enforce our laws.” If there were arrests, he presumed that ordinary law enforcement channels would suffice. The next morning, July 15, Knight received a call from Ryder Truck Rental concerned that protesters who had gathered outside Tiller’s office were being arrested and loaded into the company’s rented vehicles. In the days that followed, the arrests did not dissuade the protesters. In fact, the protests grew, and police efforts included helicopters flying overhead and blocking Kellogg Avenue. Initially, the protesters had envisioned a week-long series of events, including rallies and training in how to blockade the entrances to abortion clinics and intercept women going to the clinics. -

Rainbow Connection the Save the Date for Oct

The Rainbow Connection the Save the date for Oct. 7 Town Rainbow Connection Hall Meeting on marriage continued from page 2 … A Publication of the Advocacy Council for Human Rights September 2004 equality "I don't know why a company would go out of its way to lend sup- A town hall meeting on marriage equal- port to candidates who are that far out of the mainstream," Porter says. Calendar of Events ity is set for 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 7 in the Community Room of the Normal "If they want to have customers who are diverse and hold diverse politi- Every Wednesday Phelps Family pickets six B/N Public Library, 206 W. College Ave. cal views, it's unclear why they would want to support candidates who 7 p.m. churches, business The meeting will consist of a panel dis- are not indicative of that diverse mainstream nature." ISU PRIDE (student organization) cussion featuring gay couples, legal experts, Student Services Building Room 375 a social services specialist, and a local reli- The Human Rights Campaign, the nation's largest gay advocacy Members of Topeka's Westboro Baptist Church headed by the Rev. gious official. The discussion will center on group, gave Circuit City a low Corporate Equality Index score of 29 out Every Wednesday Fred Phelps journeyed to Bloomington Aug. 21 and 22 to picket six local 8:30 p.m. the social, religious, and legal aspects of of a possible 100. According to the survey, Circuit City does have a churches and the corporate headquarters for Electrolux. -

Long Journey Of

Photography by Brent Mykytyshyn The long journey of by Marcello Di Cintio Decades after he fled his childhood home and church, the son of America’s most controversial preacher has found a life—if not all the answers—in Calgary. God hates fags. According to the Westboro Baptist Church in To- peka, Kansas, God also hates America, Canada, and Islam. God hates Barack Obama—who, as it turns out, is the Antichrist. He hates Paul McCartney and Justin Timberlake (“The fags love him, and he them. His filth justifies their filth,” says the WBC). But God hates fags most of all. God also hates Nathan Phelps. At least that is what Nate thought on his 18th birthday in 1976, back when he still believed that God exists. At the stroke of midnight—the precise moment he legally became an adult and couldn’t be dragged back—Nate stepped out the door of his family’s Topeka compound and left the Westboro Baptist Church behind. Nate loaded a few belongings into the old Rambler he’d bought secretly for $350 and drove away. “I left there believ- ing with the same certainty that the sun is going to rise in the east that around the year 2000 Christ would come and I was going to hell,” Nate said. “I knew I would suffer for an eternity.” Nate had already suffered. For the first 18 years of his life, Nate cowered under the tyranny of his father, Fred Phelps, the extremist Calvinist preacher and disbarred lawyer who founded Westboro Baptist Church in 1955. -

Snyder V. Phelps Note

SNYDER V. PHELPS NOTE Snyder v. Phelps: Finding the Light at the End of the Tort Brendan Mackesey* I. INTRODUCTION Perplexing. This word aptly describes First Amendment jurisprudence surrounding tort claims. A number of indeterminable standards masquerade as doctrine for such claims: Is the plaintiff a public or private party? What of the defendant? Does the speech at issue regard a matter of public concern? Is it an assertion of fact? Was the plaintiff in a “public place?” Was he or she part of a “captive audience?” In Snyder v. Phelps,1 the Supreme Court has a chance to clarify some of these benchmarks. However, the Court must be wary of the influx of tort litigation its holding could trigger. Snyder presents three questions for the Supreme Court: (1) Does Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell2 apply to a private person versus another private person concerning a private matter? (2) Does the First Amendment’s freedom of speech tenet trump the First Amendment’s freedom of religion and peaceful assembly? (3) Does an individual attending a family member’s funeral constitute a captive audience who is entitled to state protection from unwanted communication?3 Analyzing these issues, the Court will determine whether a father is entitled to damages from a religious fundamentalist group that picketed with anti‐homosexual propaganda outside his son’s funeral.4 Specifically, the Court’s ruling will dictate whether a religious group may be held liable for such picketing * Brendan Mackesey is a law student at the University of Miami and winner of the 2010 University of Miami Law Review Writing Competition. -

When Bad Speech Does Good

Essay When Bad Speech Does Good Mary Anne Franks* Defenses of offensive speech typically include a distancing disclaimer, highlighting the separation between the person offering the defense and the offensive content itself.1 Consider, for example, the well-worn quotation widely misattributed to Voltaire: “I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”2 In this view, it is the principle, not the substance, of the speech that deserves respect. This view may be grounded in the belief, or some combination of beliefs, that one person’s “bad” speech is another person’s “good” speech;3 that even avowedly bad speech helps produce, or at least sharpen, good speech;4 that because the line between bad and good speech is a difficult one to draw, censorship is likely to stifle or chill good speech as well as bad speech;5 and/or that even if lines * Associate Professor of Law, University of Miami Law School; J.D., Harvard Law School; D. Phil., Oxford University. I am grateful to Michael Froomkin and Arden Rowell for helpful feedback. 1. See generally ANTHONY LEWIS, FREEDOM FOR THE THOUGHT WE HATE: A BIOGRAPHY OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT (2007) (discussing First Amendment protections of offensive speech). See also Justice Scalia’s denouncement of the expressive act protected by the First Amendment in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul: “Let there be no mistake about our belief that burning a cross in someone’s front yard is reprehensible.” R.A.V. v. City of St. -

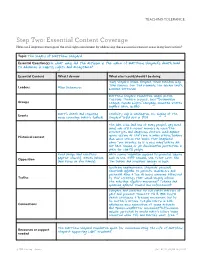

Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: The legacy of Matthew Shepard Essential Question(s): In what ways did the activism in the wake of Matthew Shepard’s death lead to advances in LGBTQ rights and acceptance? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Judy Shepard, Dennis Shepard, Jason Marsden, Rep. Leaders John Conyers, Sen. Ted Kennedy, Sen. Gordon Smith, Ellen DeGeneres Romaine Patterson Matthew Shepard Foundation, Angel Action, Groups Tectonic Theatre Project, Anti-Defamation League, Human Rights Campaign, Mountain States Against Hate, GLAAD Events Matt’s death and resulting Celebrity vigil in Washington, D.C. Signing of the news coverage. Matt’s funeral. Shepard-Byrd Act in 2009. The AIDS Crisis (and loss of many people’s gay loved ones) was still a recent memory —as were the stereotypes and dangerous rhetoric used against Historical context queer victims at the time. In many states, sodomy laws were still on the books that illegalized same-sex intimacy. As it is now, many states did not have housing or job discrimination protections in place for LGBTQ people. Fred Phelps (and Westboro Hate crimes legislation opposed by powerful figures Opposition Baptist Church), James Dobson such as Sen. Jeff Sessions, Sen. Trent Lott, Sen. (and Focus on the Family). Jim DeMint and President George W. Bush. Speaking engagements. Shepards’ personal, emotional appeals to parents, lawmakers and Tactics potential allies— a “we all know someone affected by this” strategy that would largely inform the marriage equality movement. -

America Hates the Westboro Baptist Church: the Battle to Preserve the Funerals of Fallen Soldiers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations Anthropology, Department of 12-2011 America Hates the Westboro Baptist Church: The Battle to Preserve the Funerals of Fallen Soldiers Kendra L. Suesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses Part of the Anthropology Commons Suesz, Kendra L., "America Hates the Westboro Baptist Church: The Battle to Preserve the Funerals of Fallen Soldiers" (2011). Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations. 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AMERICA HATES THE WESTBORO BAPTIST CHURCH: THE BATTLE TO PRESERVE THE FUNERALS OF FALLEN SOLDIERS By Kendra L. Suesz A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Anthropology Under the Supervision of Professor Martha McCollough Lincoln, Nebraska December 2011 AMERICA HATES THE WESTBORO BAPTIST CHURCH: THE BATTLE TO PRESERVE THE FUNERALS OF FALLEN SOLDIERS Kendra L. Suesz, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Martha McCollough The Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) has gained national attention over the past several years with their fiery protests at the funerals of soldiers killed in action. Citizens outraged by the actions of the WBC pressured the lawmakers in 45 states to enact legislation curtailing the protesters‟ access to funerals. -

Responding to the Westboro Baptist Church

Responding to the Westboro Baptist Church The Westboro Baptist Church, a small virulently homophobic, anti-Semitic hate group, regularly stages protests around the country against institutions and individuals they think support homosexuality or otherwise subvert what they believe is God's law. Targets include schools the group deems to be accepting of homosexuality; Catholic, Lutheran, and other Christian denominations that Westboro feels are heretical; and funerals for people murdered or killed in accidents like plane crashes. The organization also became well known, starting in 2005, for picketing the funerals of soldiers killed during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. While Westboro has protested against Jewish institutions over the years, they were not a major focus of the group until April 2009. Starting that year, Westboro targeted dozens of Jewish institutions, from ADL offices to Israeli consulates to synagogues to JCCs, around the country and distributed anti-Semitic fliers to announce planned protests at these sites. Westboro has also sent volumes of faxes and emails, with anti- Semitic and anti-gay messages to various Jewish institutions and individuals. Westboro’s protests at Jewish institutions began to die down a few years later but these institutions remain a target of the group. WHAT IS THE WESTBORO BAPTIST CHURCH? Based in Topeka Kansas, Westboro considers itself an “Old School” (or “Primitive”) Baptist Church. The group has no official affiliation with mainstream Baptist organizations. Most Westboro congregants are related to the group’s late founder Fred Phelps. Several of his children and his grandchildren constitute the majority of its members. Over the years, a number of the Phelps family members have left the group and denounced its hateful views. -

Westboro Baptist Church

Westboro Baptist Church This document is an archived copy of an older ADL report and may not reflect the most current facts or developments related to its subject matter. The Topeka, Kansas-based Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) is a small virulently homophobic, anti-Semitic hate group that regularly stages protests around the country, often several times a week. The group pickets institutions and individuals they think support homosexuality or otherwise subvert what they believe is God’s law. Incorporated in 1967 as a not-for-profit organization, WBC considers itself an “Old School (or Primitive)” Baptist Church. WBC’s leader is Fred Phelps and several of his children and dozens of his grandchildren appear to constitute the majority of the group’s members. WBC has no official affiliation with mainstream Baptist organizations. While WBC members have protested at Jewish institutions over the years, such institutions were not a major focus for the group until April 2009. Since then, WBC has targeted dozens of Jewish institutions around the country, from Israeli consulates to synagogues to Jewish community centers, distributing anti-Semitic fliers to announce planned protests at these sites. WBC has also been sending volumes (in some cases dozens over the course of a week) of faxes and emails with anti-Semitic and anti-gay messages to various Jewish institutions and individuals. In addition, in April 2010, the group began mailing a virulently anti-Semitic DVD to Jewish organizations and leaders. The DVD also attacks President Obama, describing him as the anti- Christ, and is filled with anti-gay and anti-Catholic vitriol.