Republic of Peru Joint Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review 28Th Session of the UPR Working Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Military on Peru's Predemocritization

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 The Impact of the Military on Peru's Predemocritization Michael Francis Plichta College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons, Military History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Plichta, Michael Francis, "The Impact of the Military on Peru's Predemocritization" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625614. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-n0ja-fg28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF THE MILITARY ON PERU'S REDEMOCRATIZATION A Thesis Presented to The faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Michael Francis Plichta 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts O s Michael Francis Plichta Approved, Mam 1990 Donald J iaxte Bartram S . Brown DEDICATION: To my parents whom I love dearly iii . TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION ............................ iii. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................. v . LIST OF TABLES .................................. vi . ABSTRACT ........................................ vii. INTRODUCTION .......................................... 2 CHAPTER I. APPROACHES TO DEMOCRATIZATION .......... 7 CHAPTER II. APPLYING A THEORY OF REDDEMOCRATIZATION TO P E R U .................................... -

World Heritage Patrimoine Mondial 41

World Heritage 41 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, June 2017 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-first session / Quarante-et-unième session Krakow, Poland / Cracovie, Pologne 2-12 July 2017 / 2-12 juillet 2017 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (Peru) (274) Sanctuaire historique de Machu Picchu (Pérou) (274) 22 - 25 February 2017 WHC-ICOMOS-IUCN-ICCROM Reactive Monitoring Mission to “Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu” (Peru) MISSION REPORT 22-25 February 2017 June 2017 Acknowledgements The mission would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Culture of Peru and the authorities and professionals of each institution participating in the presentations, meetings, fieldwork visits and events held during the visit to the property. This mission would also like to express acknowledgement to the following government entities, agencies, departments, divisions and organizations: National authorities Mr. Salvador del Solar Labarthe, Minister of Culture Mr William Fernando León Morales, Vice-Minister of Strategic Development of Natural Resources and representative of the Ministry of Environment Mr. -

The Evolving Transnational Crime-Terrorism Nexus in Peru and Its Strategic Relevance for the U.S

The Evolving Transnational Crime-Terrorism Nexus in Peru and its Strategic Relevance for the U.S. and the Region BY R. EVAN ELLIS1 n September, 2014, the anti-drug command of the Peruvian National Police, DIRANDRO, seized 7.6 metric tons of cocaine at a factory near the city of Trujillo. A Peruvian family-clan, Iin coordination with Mexican narco-traffickers, was using the facility to insert the cocaine into blocks of coal, to be shipped from the Pacific Coast ports of Callao (Lima) and Paita to Spain and Belgium.2 Experts estimate that Peru now exports more than 200 tons of cocaine per year,3 and by late 2014, the country had replaced Colombia as the world’s number one producer of coca leaves, used to make the drug.4 With its strategic geographic location both on the Pacific coast, and in the middle of South America, Peru is today becoming a narcotrafficking hub for four continents, supplying not only the U.S. and Canada, but also Europe, Russia, and rapidly expanding markets in Brazil, Chile, and Asia. In the multiple narcotics supply chains that originate in Peru, local groups are linked to powerful transnational criminal organizations including the Urabeños in Colombia, the Sinaloa Cartel in Mexico, and most recently, the First Capital Command (PCC) in Brazil. Further complicating matters, the narco-supply chains are but one part of an increasingly large and complex illicit economy, including illegal mining, logging, contraband merchandise, and human trafficking, mutually re-enforcing, and fed by the relatively weak bond between the state and local communities. -

LEAGUE of NATIONS. Tcominunicated to the Council D Members of the League,- ' Geneva, January 24 Th, 1933'

LEAGUE OF NATIONS. tCominunicated to the Council d Members of the League,- ' Geneva, January 24 th, 1933' COMMUNICATION FROM THE GOVERNMENT OF PERU. Note by the Secretary-General. The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate to the Council and Members of the League the following communication, dated January 20th, which he has received from the Government •f Peru, Sir, You have brought to the notice of my Government, and to the Members of the Council of the League of Nations, the letter sent you by the Colombian Government on January 2nd concerning the situation at LETICIA. In conformity with instructions just received, I have the honour to transmit to you the requisite details concerning the events which occurred in this town and the present divergencies between Peru and Colombia. The occupation of LETICIA by a group of Peruvians on September 1st, 1932» and the expulsion of the Colombian authorities is the origin of the present dispute. LETICIA, a port on the river Amazon, was founded by Peruvians more than a century ago. It has always been inhabited by Peruvians, but was ceded to Colombia under the Salamon-Lozano Treaty which, in I9 2 8 , fixed the frontier between the two countries. The accusations brought by the Colombian Government against the assailants are absolutely unfounded. The object of these (1} See Document C.2O.M.5 .I9 3 3 .VII. - 2 - || c. ecus' tiv>ns is to obscure the disinterested char a ct or of t no movement. Faced with a situation which ;vas bound to trouble the friendly and neighbourly relations between P. -

Resumen: En El Perú Tenemos Una Ley Que Establece La Cuota Para La Representación De Mujeres En Las Listas De Candidatos a Cargos Por Elección Que Establece El 30%

ISSN: 2617-619X Página 55 de 83 CONCIENCIA SOCIAL, PARTIDARIA, PARIDAD Y REPRESENTACIÓN DE PALAMENTARIAS DEL CONGRESO DE LA REPÚBLICA DEL PERÚ, 2020. LIMA. SOCIAL, PARTIAL, PARITY AND REPRESENTATION AWARENESS OF PALAMENTARIES OF THE CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC DEL PERÚ, 2020. LIMA. CONSCIÊNCIA SOCIAL, PARCIAL, DE PARIDADE E DE REPRESENTAÇÃO DE PALAMENTÁRIOS DO CONGRESSO DA REPÚBLICA DEL PERÚ, 2020. LIMA. HERNÁNDEZ AGUILAR, Zoila1 Doris SANCHEZ PINEDO 2 ISSN: 2617-619X Resumen: En el Perú tenemos una ley que establece la cuota para la representación de mujeres en las listas de candidatos a cargos por elección que establece el 30%. Se pretende la paridad, la democracia representativa paritaria que tendría su marco en la igualdad de posiciones y derechos en los poderes públicos, los agentes ambientales, económicos, políticos, jurídicos y sociales. Especialmente en los ciudadanos y ciudadanas quienes otorgarán a la igualdad no solo un valor político, social, jurídico, sino un valor democrático para lo cual es perentorio que las bases partidarias mismas concilien para llegar al acuerdo, al 1 Directora de la ONG Mujer y Sociedad. 2 Dra. en Biología. Docente invitada de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. Dra (c) en Educación, Dra (c) Ciencias Sociales. Decana de Educación del Instituto Internacional de Gobierno (IGOB) IGOBERNANZA | AÑO 3. N° 9 – 2020 ISSN: 2617-619X Página 56 de 83 pacto de que es urgente modificar las estructuras del poder para que una de las grandes brechas para tener una distribución real de democracia representativa se supere, ni más hombres, ni más mujeres sino el principio de equilibrio para un real valor democrático y una condición sine qua non de ciudadanía y existencia. -

Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean 363.1098 Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean

Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean 363.1098 Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean. R425 / Coordinated by Lucia Dammert. Santiago, Chile: FLACSO, 2007. 204p. ISBN: 978-956-205-217-7 Security; Public Safety; Defence; Intelligence Services; Security Forces; Armed Services; Latin America Cover Design: Claudio Doñas Text editing: Paulina Matta Correction of proofs: Jaime Gabarró Layout: Sylvio Alarcón Translation: Katty Hutter Printing: ALFABETA ARTES GRÁFICAS Editorial coordination: Carolina Contreras All rights reserved. This publication cannot be reproduced, partially or completely, nor registered or sent through any kind of information recovery system by any means, including mechanical, photochemical, electronic, magnetic, electro-visual, photocopy, or by any other means, without prior written permission from the editors. First edition: August 2007 I.S.B.N.: 978-956-205-217-7 Intellectual property registration number 164281 © Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO-Chile, 2007 Av. Dag Hammarskjöld 3269, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile [email protected] www.flacso.cl FLACSO TEAM RESPONSIBLE FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE REPORT ON THE SECURITY SECTOR Lucia Dammert Director of the Security and Citizenship Program Researchers: David Álvarez Patricia Arias Felipe Ajenjo Sebastián Briones Javiera Díaz Claudia Fuentes Felipe Ruz Felipe Salazar Liza Zúñiga ADVISORY COUNCIL Alejandro Álvarez (UNDP SURF LAC) Priscila Antunes (Universidad Federal de Minas Gerais – Brazil) Felipe -

Proposal Template

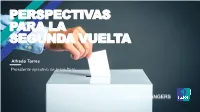

PERSPECTIVAS PARA LA SEGUNDA VUELTA Alfredo Torres Presidente ejecutivo de Ipsos Perú CONTEXTO 2 ‒ © Ipsos | Segunda vuelta y retos de la gobernabilidad Según el Ipsos Disruption Barometer (IDB) el Perú es el país con mayor riesgo sociopolítico entre los 30 que mide globalmente. Australia Cambio vs antes del COVID 28% Diciembre 2019 Subió *Arabia Saudí 28% Mejor opinión Sin cambio del consumidor *China Bajó 23% / ciudadano y estabilidad Gran Bretaña 19% sociopolítica NORMA Hungría 12% HISTÓRICA Por país Peor opinión Alemania -19% del consumidor / ciudadano y *Argentina -25% estabilidad sociopolítica Polonia -30% *Chile -41% *Perú -50% * La muestra es más urbana, por lo que las personas El IDB es una combinación de 4 variables: Evaluación de la situación general 3 ‒ © Ipsos | Nombre del documento tienden a tener un nivel educativo y de ingresos y económica del país, percepción a futuro sobre la economía en su localidad, mayor que la población en general percepción personal de situación financiera actual y a futuro, y percepción sobre seguridad laboral para el entorno cercano. El IDB de Perú empezó a caer a fines de 2019 y está ahora en su mínimo histórico Bandera verde = estabilidad económica, estabilidad sociopolítica Anuncio -Vizcarra es adelanto de Renuncia -PPK renuncia - vacado PPK elecciones Gabinete Vizcarra -Merino presidente Referéndum Congresales Zavala presidente presidente (Jul16) (Dic18) (Jul19) -Protestas Mejor -Censura a (Set17) (Mar18) -Coronavirus masivas opinión del Saavedra -Nuevo -Renuncia consumidor -Indulto -

OSAC Encourages Travelers to Use This Report to Gain Baseline Knowledge of Security Conditions in Peru

Peru 2020 Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in Lima. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in Peru. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s country-specific page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Peru at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution. Do not travel to the Colombian border area in the Loreto Region due to crime, or the area in central Peru known as the Valley of the Rivers Apurimac, Ene, and Mantaro (VRAEM) due to crime and terrorism. Overall Crime and Safety Situation Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Lima as being a CRITICAL-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. According to the Peruvian National Police (PNP), crime increased 13% in 2019. Foreign residents and visitors may be more vulnerable to crime, as criminals perceive them to be wealthier and more likely to carry large amounts of cash and other valuables on their person. However, this uptick in crime has affected Peruvians and foreigners alike. The most common types of crime in Lima and many parts of the country include armed robbery, assault, burglary, and petty theft. Crimes can turn violent quickly, and often escalate when a victim attempts to resist. -

Nuevo Folleto Planes De Gobierno Agenda Para El Desarrollo

PROPUESTAS DE PLANES DE GOBIERNO DE CANDIDATOS PRESIDENCIALES ELECCIONES GENERALES 2021 Nuestro país se apresta a elegir a sus más altas autoridades en medio de una crisis económica, inestabilidad política y emergencia sanitaria. Ello hace que el momento sea aún más apremiante de lo que siempre son unas elecciones generales para presidente y congresistas. La Agenda para el Desarrollo de Arequipa, que conforman las universidades Católica de Santa María, Católica San Pablo y Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa; no podía mantenerse al margen dado su compromiso con la solución de los problemas del país en general y de nuestra Región en particular. Entendemos que la abundancia de candidatos y organizaciones políticas que participan no contribuye a una fácil identificación con las propias convicciones; por lo que la Agenda ha elaborado un documento que permite conocer de una manera sencilla y clara las propuestas de cada candidato presidencial para cada uno de los aspectos más importantes de la vida del país. Hemos actuado con total objetividad y neutralidad, evitando interpretaciones y procurando, por el contrario, transcribir fielmente las propuestas de los documentos oficiales de cada agrupación política. Esperamos que la ciudadanía encuentre de utilidad la información presentada y le ayude a votar de manera informada. Dr. Rohel Sánchez Sánchez Rector Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa PROPUESTAS EN LA DIMENSIÓN SOCIAL PROPUESTAS EN LA DIMENSIÓN SOCIAL PARTIDO / Para la Familia Para la Educación Para la Salud Para la Pobreza CANDIDATO • Madres gestantes e hijos, desde que • Más presupuesto para la educación • Construcción del sistema único y • Creación del programa de implementación nacen, recibirán atención que permita cerrar brechas de público de salud, integración de todos de Zonas de Integración Fronteriza especializada, consejería psicológica, cobertura y calidad con un enfoque de los sistemas de salud en uno solo. -

LA CRISIS POLÍTICA En Medio De La Grave Crisis Sanitaria, Económica Y

LA CRISIS POLÍTICA En medio de la grave crisis sanitaria, económica y social ocasionada por la pandemia del COVID 19, el país se vio enfrentado a una grave crisis política por el intento del Congreso de vacar al Presidente Martín Vizcarra. En efecto, el viernes 10 de setiembre la admisión de la moción de vacancia fue votada con el siguiente resultado Como vemos en el cuadro, los impulsores de la moción de vacancia fueron Acción Popular (AP), Alianza para el Progreso (APP), Unión por el Perú (UPP) y Podemos. El origen formal de esta crisis fue la entrega de tres audios a Jorge Alarcón, Presidente de la Comisión de Fiscalización del Congreso, por parte de Karem Roca Luque, asistente administrativa de Palacio, quien trabajó con Vizcarra durante 10 años, en Moquegua y en el Ministerio de Transporte y 1 Comunicaciones y formaba parte del círculo de confianza del Presidente. Sin embargo su relación se había deteriorado por la pugna que mantenía con Mirian Morales Córdova, secretaria general de la Presidencia de la República. En los audios se nota que Karem Roca está resentida porque siente que ya no cuenta con el respaldo absoluto del Presidente Vizcarra. La credibilidad de Roca ha quedado mellada por haberse desdicho en varias afirmaciones en la última semana, como por ejemplo en la acusación que hizo a la Marina de Guerra de ser la autora del chuponeo y luego retiró. En dos de los tres se escucha al Presidente, a Karem Roca, a Miriam Morales coordinar sus respuestas frente a la investigación sobre Richard Cisneros (Swing) quien fue contratado nueve veces por el Ministerio de Cultura, entre octubre de 2018 y abril del 2020 durante las gestiones de Kuczynski y Vizcarra, por aproximadamente S/175 mil. -

UN CUERPO AMBULANTE Sergio Zevallos En El Grupo Chaclacayo

UN CUERPO AMBULANTE A WANDERING BODY Sergio Zevallos en Sergio Zevallos in el Grupo Chaclacayo the Grupo Chaclacayo (1982-1994) (1982-1994) 2 UN3 CUERPO AMBULANTE A WANDERING BODY Sergio Zevallos en Sergio Zevallos in el Grupo Chaclacayo the Grupo Chaclacayo (1982-1994) (1982-1994) Editado por / Edited by Miguel A. López PUBLICACIÓN EXPOSICIÓN AGRADECIMIENTOS AGRADECIMIENTOS DEL ARTISTA Edición Curaduría A Raúl Avellaneda y Helmut Psotta por los años Miguel A. López Miguel A. López de Lima – MALI - Coordinación editorial Coordinación Gabriela Germaná Valeria Quintana al Museo Travesti del Perú. www.mali.pe Metropolitana de Lima Concepto y diseño Fotografía Daniel Giannoni Ralph Bauer los autores Musuk Nolte Museografía Berlin Nord. Traducción los autores Nelson Munares Melanie Gallagher Flavia López de Romaña Valerie Berger Sharon Lerner ISBN 978-9972-718-39-7 Museo de Arte de Lima MALI Retoque 16 de noviembre de 2013 del Perú 23 de marzo de 2014 Impresión Centro Cultural de España – Lima 16 de noviembre de 2013 Reservados todos los 19 de enero de 2014 Wüttembergischer Kunst verein Stuttgart Alemania Museo de Arte de Lima – MALI al fondo hay sitio del Sur y VAGA. MUSEO DE ARTE DE LIMA PRESIDENTE DIRECCIÓN CURADURÍA DE EXPOSICIONES EDUCACIÓN IMAGEN Y MARKETING COLECCIONES Y PUBLICACIONES Y DE ARTE Jimena González DIRECTOR VICEPRESIDENTES GERENCIA GENERAL PRECOLOMBINO Comunicación y prensa Asistente Marilyn Lavado Primer Vicepresidente Asistente Asistente de gerencia -

Survey for Review of Chemical Management Regulatory Systems Worldwide

Survey for Review of Chemical Management Regulatory Systems Worldwide Committee on Trade and Investment (CTI) Chemical Dialogue 2018 APEC Project: CD 02 2017S Produced by Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation Сhemical-technological and Forestry Complex Department 7 Kitaigorodsky Proyezd 109074, Moscow, the Russian Federation Tel: +7-495-632-81-05 Email: [email protected] Website: www.minpromtorg.gov.ru Coordinating Informational Center of CIS member states on approximation of regulatory practices (CIS Center) 36/1 Liusinovskaya street 115093, Moscow, the Russian Federation Tel: +7- 495-745-38-00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ciscenter.org Australian Government Department of Industry and Science Industry House 10 Binara Street Canberra City ACT 2601 GPO Box 9839, Canberra ACT 2601 Tel: 61-2-6213-7821 Email: [email protected] Website: www.industry.gov.au For Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Secretariat 35 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119616 Tel: (65) 68919 600 Fax: (65) 68919 690 Email: [email protected] Website: www.apec.org 2018 APEC Secretariat CD 02 2018S ISBN/ISSN ___-__-____-_____-__ 2 CONTENT INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................8 International regulatory framework for safe handling of chemical products ........................11 1.1. Safe management of chemicals in the globalization context............................................12 1.2. Basic principles of the global agenda on safe management of chemicals .......................13 1.3. International policies for the technical regulation of chemical products .......................17 1.4. International agreements and conventions that form the bedrock of the modern system of safe management of chemicals ..................................................................................................21 1.5. International statutory regulation of chemicals in various industrial sectors ...............24 1.6.