OECD/DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION and SCIENCE, IRELAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Independent

gjj Dan O'Brien The Irish are becoming EXCLUSIVE ‘I was hoping he’d die,’ Jill / ungovernable. This Section, Page 18Meagher’s husband on her murderer. Page 20 9 6 2 ,0 0 0 READERS Vol. 109 No. 17 CITY FINAL April 27,2014 €2.90 (£1.50 in Northern Ireland) lMELDA¥ 1 1 P 1 g§%g k ■MAY ■ H l f PRINCE PHILIP WAS CHECKING OUT MY ASS LIFE MAGAZINE ALL IS CHANGING, CHANGING UTTERLY. GRAINNE'SJOY ■ Voters w a n t a n ew political p arty Poll: FG gets MICHAEL McDOWELL, Page 24 ■ Public demands more powers for PAC SHANE ROSS, Page 24 it in the neck; ■ Ireland wants Universal Health Insurance -but doesn'tbelieve the Governmentcan deliver BRENDAN O'CONNOR, Page 25 ■ We are deeply suspicious SF rampant; of thecharity sector MAEVE SHEEHAN, Page 25 ■ Royal family are welcome to 1916 celebrations EILISH O'HANLON, Page 25 new partycall LOVE IS IN THE AIR: TV presenter Grainne Seoige and former ■ ie s s a Childers is rugbycoach turned businessman Leon Jordaan celebrating iittn of the capital their engagement yesterday. Grainne's dress is from Havana EOGHAN HARRIS, Page 19 in Donnybrookr Dublin 4. Photo: Gerry Mooney. Hayesfaces defeat in Dublin; Nessa to top Full Story, Page 5 & Living, Page 2 poll; SF set to take seat in each constituency da n ie l Mc Connell former minister Eamon Ryan and JOHN DRENNAN (11 per cent). MillwardBrown Our poll also asked for peo FINE Gael Junior Minister ple’s second preference in Brian Hayes is facing a humil FULL POLL DETAILS AND ANALYSIS: ‘ terms of candidate. -

1. the Politics of Legacy

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Succeeding in politics : dynasties in democracies Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1dv7f7bb Authors Smith, Daniel Markham Smith, Daniel Markham Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Succeeding in Politics: Dynasties in Democracies A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Daniel Markham Smith Committee in charge: Professor Kaare Strøm, Chair Professor Gary W. Cox Professor Gary C. Jacobson Professor Ellis S. Krauss Professor Krislert Samphantharak Professor Matthew S. Shugart 2012 ! Daniel Markham Smith, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Daniel Markham Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION To my mother and father, from whom I have inherited so much. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature page……………………………………………………………………………iii Dedication………………………………………………………………………………...iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………….v List of Abbreviations………………………….………………………………………....vii List of Figures……………………………...……………………………………………viii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………...x Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………….xii Vita………………………………………………………………………………………xv Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….xvi 1. The -

State Involvement in the Magdalene Laundries

This redacted version is being made available for public circulation with permission from those who submitted their testimonies State involvement in the Magdalene Laundries JFM’s principal submissions to the Inter-departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalene Laundries Compiled by1: Dr James M. Smith, Boston College & JFM Advisory Committee Member Maeve O’Rourke, JFM Advisory Committee Member 2 Raymond Hill, Barrister Claire McGettrick, JFM Co-ordinating Committee Member With Additional Input From: Dr Katherine O’Donnell, UCD & JFM Advisory Committee Member Mari Steed, JFM Co-ordinating Committee Member 16th February 2013 (originally circulated to TDs on 18th September 2012) 1. Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) is a non-profit, all-volunteer organisation which seeks to respectfully promote equality and advocate for justice and support for the women formerly incarcerated in Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries. Many of JFM’s members are women who were in Magdalene Laundries, and its core coordinating committee, which has been working on this issue in an advocacy capacity for over twelve years, includes several daughters of women who were in Magdalene Laundries, some of whom are also adoption rights activists. JFM also has a very active advisory committee, comprised of academics, legal scholars, politicians, and survivors of child abuse. 1 The named compilers assert their right to be considered authors for the purposes of the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000. Please do not reproduce without permission from JFM (e-mail: [email protected]). 2 Of the Bar of England and Wales © JFM 2012 Acknowledgements Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) gratefully acknowledges The Ireland Fund of Great Britain for its recent grant. -

Report of the Forum on Parliamentary Privilege

Report of the Forum on Parliamentary Privilege As made to the Ceann Comhairle, Mr Seán Ó Fearghaíl TD 21st December 2017 Table of Contents Membership of Forum 2 Chair’s introduction 3 1. Summary of recommendations 4 2. Background to the Forum 6 3. The Forum’s Work Programme 7 4. Themes from submissions received 9 5. The Constitution 11 6. Parliamentary privilege in other jurisdictions 14 7. Forum’s recommendations 16 8. Matters not recommended for change by the Forum 21 Appendix A – Procedure in other parliaments 22 Appendix B – Parliaments examined 23 Appendix C – Draft guidelines on the use by members of their constitutional privilege of freedom of debate 24 Appendix D – Standing Order 61 25 Appendix E – Standing Order 59 29 Appendix F – Summary of rules in parliaments examined 30 Appendix G – Forum terms of reference, advertisement, data protection policy, etc. 36 Appendix H – Submissions 42 1. Mr Kieran Fitzpatrick 42 2. Dr Jennifer Kavanagh 51 3. Deputies Clare Daly and Mick Wallace 53 4. Mr Kieran Coughlan 58 5. Deputy Mattie McGrath 65 6. Deputy Josepha Madigan 67 7. Sinn Féin 69 8. Deputy Catherine Murphy 70 9. Deputy Danny Healy Rae 71 10. Solidarity-People Before Profit 72 11. Deputy Lisa Chambers 77 12. Deputy Brendan Howlin, Labour Party leader 79 13. Deputy Eamon Ryan 83 14. Fianna Fáil 85 15. Association of Garda Sergeants and Inspectors 88 16. Fine Gael 95 1 Membership of Forum Membership of Forum on Parliamentary Privilege1 David Farrell, academic (Chair) Professor David Farrell holds the Chair of Politics at UCD where he is Head of Politics and International Relations. -

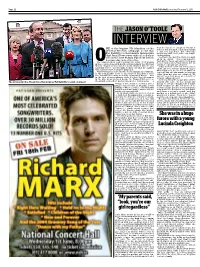

INTERVIEW That She Had Been Adopted

Page 22 Irish Daily Mail, Saturday, February 12, 2011 THE JASON O’TOOLE INTERVIEW that she had been adopted. ‘It’s when NE of the biggest PR blunders of the you’re a kid, you kind of half understand General Election campaign so far was it and you half don’t. But obviously Pat Rabbitte’s chauvinistic insinuation my parents said, “look, you’re our daugh- that Averil Power was only offered a key ter regardless”. role in the new Fianna Fáil front bench ‘And that’s the way it is. You’re brought up in the family — that’s my parents, because she was attractive. that my brothers and sister. I suppose OThe former Labour leader managed to insult every woman it’s not talked about that much, but an in the country along with Averil, with his remark that Micheál awful lot of people are adopted. Martin ‘might as well wander down Grafton Street’ and ‘I was born in 1978 and if you had a randomly select ‘good-looking women’ for what he claimed child and you weren’t married, that’s was a ‘stunt for photographic purposes’. what happened. So, there’s an awful lot What Pat may not have known, before making his comment, of people my age and maybe a few years is the remarkable story of an adopted daughter’s swift older than me who are adopted. We rise through the ranks in a male dominated world — and haven’t been very good, as a society, of in the face of extraordinary odds. Or that the tall woman actually talking about it.’ in the blue dress, pictured beside the Fianna Fáil leader on Averil’s political life began while still in The woman in blue: The picture that inspired Pat Rabbitte’s sexist comment the plinth of the Dáil, had grown up in a loving home — a Trinity. -

The Irish Jewish Museum

2009 Learning from the past ~ lessons for today The Holocaust Memorial Day Committee in association with the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform; Dublin City Council; Dublin Maccabi Charitable Trust and the Jewish Representative Council of Ireland The Crocus International Project The Holocaust Educational Trust of Ireland invites school children to plant yellow crocuses in memory of one and a half million Jewish children and thousands of other children who were murdered during the Holocaust. Crocuses planted in the shape of a star of David by pupils of St Martin’s Primary School, Garrison, Co Fermanagh, Northern Ireland Holocaust Memorial Day 2009 National Holocaust Memorial Day Commemoration Sunday 25 January 2009 Mansion House, Dublin Programme MC: Yanky Fachler Voice: Moya Brennan Piper: Mikey Smith • Introductory remarks: Yanky Fachler • Words of welcome: Lord Mayor of Dublin, Councillor Eibhlin Byrne • Keynote address: President of Ireland, Mary McAleese • The Stockholm Declaration: Swedish Ambassador to Ireland, Mr Claes Ljungdahl Musical interlude: Moya Brennan • The Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform: Sean Aylward, General Secretary • HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR: TOMI REICHENTAL • The Holocaust: Conor Lenihan TD, Minister for Integration • The victims of the Holocaust: Niall Crowley, former CEO of the Equality Authority • Book burning: Professor Dermot Keogh, University College Cork • The Évian Conference: Judge Catherine McGuinness, President of the Law Reform Commission • Visa appeals on behalf of Jews in Europe: -

Women As Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems*

Women as Executive Leaders: Canada in the Context of Anglo-Almerican Systems* Patricia Lee Sykes American University Washington DC [email protected] *Not for citation without permission of the author. Paper prepared for delivery at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference and the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences, Concordia University, Montreal, June 1-3, 2010. Abstract This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women as a group. Various positions of executive leadership provide a range of opportunities to investigate and analyze the experiences of women – as prime ministers and party leaders, cabinet ministers, governors/premiers/first ministers, and in modern (non-monarchical) ceremonial posts. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo- American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage. Placing Canada in this context reveals that its female executives face the same challenges as women in other Anglo countries, while Canadian women also encounter additional obstacles that make their environment even more challenging. Sources include parliamentary records, government documents, public opinion polls, news reports, leaders’ memoirs and diaries, and extensive elite interviews. This research identifies the obstacles and opportunities women as executives encounter and explores when, why, and how they might engender change by advancing the interests and enhancing the status of women. Comparative analysis indicates that the institutions, ideology, and evolution of Anglo-American democracies tend to put women as executive leaders at a distinct disadvantage. -

Thesis Title Page Vol 2

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) National self image: Celtic mythology in primary education in Ireland, 1924-2001 dr. Frehan, P.G. Publication date 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): dr. Frehan, P. G. (2011). National self image: Celtic mythology in primary education in Ireland, 1924-2001. Eigen Beheer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:24 Sep 2021 Chapter 4. Appendix I. Ministers of Education 1919 – 2002. 66 8 Feb ‘33 Council (C/6) Minister Dates Time in Office Comment 9 Mar ’32 – 2 Jan ’33. 1. John J. O Kelly 26 Aug ’21 – 4 ½ months Non -Cabinet Minister / 2 nd 11. Thomas Derrig 8 Feb ’33 – 4 years & 5 8th Dail / 7th Executive (Sceilg) 9 Jan ‘22 Dail / 21 July ‘37 months Council (C/7) 1st Ministry (Pre-Treaty) 8 Feb ’33 – 14 June ’37. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 709 Wednesday, No. 3 19 May 2010 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Wednesday, 19 May 2010. Leaders’ Questions ……………………………… 529 Ceisteanna—Questions Taoiseach ………………………………… 535 Requests to move Adjournment of Dáil under Standing Order 32 ……………… 543 Order of Business ……………………………… 544 Issue of Writ: Waterford By-election ………………………… 556 Euro Area Loan Facility Bill 2010: Second Stage (resumed)………………… 563 Message from Select Committee ………………………… 570 Ceisteanna—Questions (resumed) Minister for Tourism, Culture and Sport Priority Questions …………………………… 570 Other Questions …………………………… 580 Adjournment Debate Matters …………………………… 591 Euro Area Loan Facility Bill 2010: Second Stage (resumed) …………………………… 592 Committee and Remaining Stages ……………………… 617 Private Members’ Business Constitutional Amendment on Children: Motion (resumed) ……………… 632 Adjournment Debate Job Losses ………………………………… 654 Drug Treatment Programme ………………………… 656 Energy Resources ……………………………… 657 Schools Building Projects …………………………… 659 Questions: Written Answers …………………………… 663 DÁIL ÉIREANN ———— Dé Céadaoin, 19 Bealtaine 2010. Wednesday, 19 May 2010. ———— Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 10.30 a.m. ———— Paidir. Prayer. ———— Leaders’ Questions. Deputy Enda Kenny: We cannot have a sound economy without small businesses. Three years ago, 800,000 people worked in the small business sector, in tourism, services and manufac- turing. That number has declined to 700,000 and on current projections is likely to further decrease to 600,000 next year. The banking strategy set out by the Government has failed in so far as small businesses are concerned. The Taoiseach said that we will write whatever cheques are necessary. Those cheques have thus far amounted to €74 billion in taxpayers’ money. When the guarantee scheme was introduced, the Minister for Finance stated that the Government is deeply embed- ded in the banking sector and, as such, would bring leverage to it. -

Summer's Wreath

Summer’s wreath A celebration of 2010 William ButlerYeats National Library of Ireland Kildare Street, Dublin 2 01 603 0277 [email protected] www.nli.ie NEWS Number 40: Summer 2010 National Library of Ireland WilliamJune 2Butlernd - 30 Yeatsth 201 0was born in June 1865 into one of Ireland’s great artistic families. This year, his creativity and Admission free legacy is again celebrated in Summer’s Wreath, a month-long public programme of events run in conjunction with the Library’s current exhibition Yeats: the life and works of William Butler Yeats. The programme will feature lunchtime readings and reflections on his life and his poetry, evening lectures, recitals and music by leading names as well as a one-day course on Yeats’ poetry. The evening series of events began on Wednesday 2 June when award-winning actress and director Anjelica Huston discussed her life-long love affair with Yeats’ poetry with broadcaster John Kelly. It will be followed on Tuesday 15 June by ‘From Ballads to Byzantium’, readings and recitals by the author and Abbot of Glenstal Abbey Mark Patrick Hederman and internationally acclaimed spiritual singer Nóirín Ní Ríain. On Monday 21 June, Cerys Matthews, former lead singer with the Welsh rock band Catatonia, will reflect on her love for the magic found in Celtic poetry and song, including the poetry of WB Yeats. On Wednesday 23 June, Professor Germaine Greer will give a lecture entitled Yeats and Women : D esire and Dread. On Monday 28 June, jazz vocalist Christine Tobin will give a performance Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann featuring the poetry of Yeats set to music. -

Directory of Local Studies Articles and Book Chapters in Dún Laoghaire

Directory of Local Studies Articles and Book Chapters in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown Compiled by: Nigel Curtin, Local Studies Librarian, dlr Library Service This publication lists articles, book chapters and websites published on subjects relating to the county of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown. It is based primarily on material available in dlr Libraries Local Studies Collection. It does not represent an exhaustive listing but should be considered as a snapshot of material identified by the Local Studies Librarian from 2014 to 2021. Its purpose is to assist the researcher in identifying topics of interest from these resources in the Collection. A wide ranging list of monographs on the topics covered in the Directory can also be found by searching dlr Libraries online catalogue at https://libraries.dlrcoco.ie/ Directory of Local Studies Articles and Book Chapters in Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown dlr Local Studies, 5th Floor dlr LexIcon, Haigh Terrace, First published 2021 by Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council Moran Park, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin E: [email protected] T: 01 280 1147 Compiled by Nigel Curtin W: https://libraries.dlrcoco.ie ISBN 978-0-9956091-3-6 Book and cover design by Olivia Hearne, Concept 2 Print Printed and bound by Concept 2 Print dlrlibraries @dlr_libraries Libraries.dlr https://bit.ly/3up3Cy0 3 Contents PAGE Journal Articles 5 Book Chapters 307 Web Published 391 Reports, Archival Material, 485 Unpublished Papers, Manuscripts, etc. Temporary bridge over Marine Road, Kingstown, 31 August 1906. The bridge connected Town Hall with the Pavilion on the occasion of the Atlantic 3 Fleet Ball. 5 Directory of Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown Local Studies YEAR BOOK TITLE CHAPTER or reference AUTHOR WEBLINKS or notes Journal Articles Bullock Harbour, 1860s. -

JOURNAL of CROSS BORDER STUDIES in IRELAND No

THE JOURNAL OF CROSS BORDER STUDIES IN IRELAND No. 4 with information about the CENTRE FOR CROSS BORDER STUDIES (including 2008 annual report) Spring 2009 - Year 10 featuring an interview with Northern Ireland First Minister Peter Robinson 1 JOURNAL OF CROSS BORDER STUDIES IN IRELAND No.4 THE JOURNAL OF CROSS BORDER STUDIES IN IRELAND Cartoon by Martyn Turner The Centre is part-financed by the European Union’s European Regional Development Fund through the INTERREG IVA Cross-border Programme managed by the Special EU Programmes Body Editor: Andy Pollak ISBN: 978-1-906444-22-8 3 JOURNAL OF CROSS BORDER STUDIES IN IRELAND No.4 The Minister for Education and Science, Ms Mary Hanafin TD, launches the 2008 ‘Journal of Cross Border Studies in Ireland’. From left to right: Mr Niall Holohan, Southern Deputy Joint Secretary, North/South Ministerial Council; Professor Ferdinand von Prondzynski, President, Dublin City University; Ms Hanafin; HE David Reddaway, British Ambassador to Ireland; Ms Mary Bunting, Northern Joint Secretary, North/South Ministerial Council; Dr Chris Gibson, CCBS Chairman; Mr Michael Kelly, Chairman, Higher Education Authority. CONTENTS A word from the Chairman 05 Chris Gibson “Business to be done and benefits to be gained”: The views 11 of Northern Ireland’s First Minister, Peter Robinson, on North-South cooperation What role for North-South economic cooperation in 19 a time of recession? Interviews with six business leaders and economists Andy Pollak and Michael D’Arcy Cross-border banking in an era of financial crisis: