Feasibility Study Implementation of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

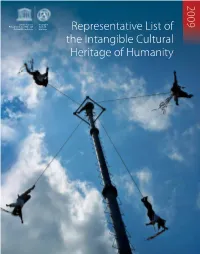

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Of

RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 2 2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity RL cover [temp]:Layout 1 1/6/10 17:35 Page 5 Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Intangible Cultural Heritage Domains

Intangible Cultural Heritage Domains Intangible Cultural Heritage 172 Intangible cultural dinand de Jong r UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible e o © F hot Cultural Heritage proposes five broad ‘domains’ in which intangible P cultural heritage is manifested: I Oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; tsev I Performing arts; o © A.Bur hot P LL The Kankurang, I Social practices, rituals and festive events; Manding Initiatory Rite, Senegal and Gambia I Knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; L The Olonkho, Yakut Heroic Epos, Russian Federation I Traditional craftsmanship. J The Carnival of Binche, Belgium heritage domains Instances of intangible cultural heritage are not might make minute distinctions between , limited to a single manifestation and many variations of expression while another group itage include elements from multiple domains. Take, considers them all diverse parts of a single form. ultural Her for example, a shamanistic rite. This might adagascar e of M tment of C involve traditional music and dance, prayers and While the Convention sets out a framework for ultur epar songs, clothing and sacred items as well as ritual identifying forms of intangible cultural heritage, y of C o © D inistr hot P and ceremonial practices and an acute the list of domains it provides is intended to be M awareness and knowledge of the natural world. inclusive rather than exclusive; it is not Similarly, festivals are complex expressions of necessarily meant to be ‘complete’. States may aiapi intangible cultural heritage that include singing, use a different system of domains. -

The Poetic Power of Place

The PoeTic Power of Place comparative perspectives on austronesian ideas of locality The PoeTic Power of Place comparative perspectives on austronesian ideas of locality edited by James J. fox a publication of the department of anthropology as part of the comparative austronesian project, research school of pacific studies the australian national university canberra ACT australia Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published in Australia by the Department of Anthropology in association Australian National University, Canberra 1997. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry The poetic power of place: comparative perspectives on Austronesian ideas of locality. Bibliography. Includes Indeex ISBN 0 7315 2841 7 (print) ISBN 1 920942 86 6 (online) 1. Place (Philosophy). 2. Sacredspace - Madagascar. 3. Sacred space - Indonesia. 4. Sacred space - Papua New Guinea. I. Fox, James J., 1940-. II. Australian National University. Dept. of Anthropology. III. Comparative Austronesian Project. 291.35 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Typesetting by Margaret Tyrie/Norma Chin, maps and drawings by Keith Mitchell/Kay Dancey Printed at National Capital Printing, Canberra © The several authors, each in respect of the paper presented, 1997 This edition © 2006 ANU E Press Inside Austronesian Houses Table of Contents Acknowledgements ix Chapter 1. Place and Landscape in Comparative Austronesian Perspective James J. Fox 1 Introduction 1 Current Interest in Place and Landscape 2 Distinguishing and Valorizing Austronesian Spaces 4 Situating Place in a Narrated Landscape 6 Topogeny: Social Knowledge in an Ordering of Places 8 Varieties, Forms and Functions of Topogeny 12 Ambiguities and Indeterminacy of Place 15 References 17 Chapter 2. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, 2009; 2010

2009 United Nations Intangible Educational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 1 2009 Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 2 © UNESCO/Michel Ravassard Foreword by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO UNESCO is proud to launch this much-awaited series of publications devoted to three key components of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding, the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and the Register of Good Safeguarding Practices. The publication of these first three books attests to the fact that the 2003 Convention has now reached the crucial operational phase. The successful implementation of this ground-breaking legal instrument remains one of UNESCO’s priority actions, and one to which I am firmly committed. In 2008, before my election as Director-General of UNESCO, I had the privilege of chairing one of the sessions of the Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, in Sofia, Bulgaria. This enriching experience reinforced my personal convictions regarding the significance of intangible cultural heritage, its fragility, and the urgent need to safeguard it for future generations. Rep List 2009 2.15:Layout 1 26/5/10 09:25 Page 3 It is most encouraging to note that since the adoption of the Convention in 2003, the term ‘intangible cultural heritage’ has become more familiar thanks largely to the efforts of UNESCO and its partners worldwide. -

Dwelling in Political Landscapes Contemporary Anthropological Perspectives

Dwelling in Political Landscapes Contemporary Anthropological Perspectives Edited by Anu Lounela, Eeva Berglund and Timo Kallinen Studia Fennica Anthropologica Studia Fennica Anthropologica 4 The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia Fennica Editorial Board Editors-in-chief Pasi Ihalainen, Professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Timo Kallinen, Professor, University of Eastern Finland Laura Visapää, Title of Docent, University Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Riikka Rossi, Title of Docent, University Researcher, University of Helsinki, Finland Katriina Siivonen, Title of Docent, University Teacher, University of Turku, Finland Lotte Tarkka, Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Deputy editors-in-chief Anne Heimo, Title of Docent, University of Turku, Finland Saija Isomaa, Professor, University of Tampere, Finland Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, Title of Docent, Researcher, University of Tampere, Finland Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, Postdoctoral Researcher, Dr. Phil., University of Helsinki, Finland Salla Kurhila, Title of Docent, University Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Kenneth Sillander, Adjunct Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. -

Special Section "Anthropology in the Museum"

ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE MUSEUM Intramuction Three years ago the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford .celebrated its hundredth anniversary, an occasion marked by JASOwith a Special Issue CV olume XIV, no. 2) and the publication of 'lhe Genera Z ' s Gift: A Celebration of the Pitt Rivers Museum Centenaray 1884-1984 [JASO Occasianal Papers no. 4]. Last year saw the opening of the Balfour Building, the first stage of the new Pitt Rivers Museum, named after its benefactor, the son of the Museum's. first curator. The Balfour Building has provided limited but much-needed addi tional space for the display of the Pitt Rivers collections. The new space is given over to two exhibitions, one devoted to musical instruments and the other to hunter-gatherer material. To mark this important development in ~ford anthropology these exhibi tions are reviewed here (see below pp. 64-7 and 67-9) by Margaret Birley and P.L. Carter, specialist museum curatorial staff with first-hand experience of organising such displays. Exhibitions of ethnographic material, such as those reviewed below, have many possible purposes, publics to reach, and demands to fulfil, as well as presenting rather different problems to their organisers from those faced by anthropologists when writing academic articles and books. An exhibitian such as Making Light W~k at the Pitt Rivers Museum develops an aspect of the Museum's permanent collection and the use made of it by a contemporary artist. The account of the exhibition given here (pp. 60-3) by the exhibition's organiser, Linda Cheetham, throws light on the way in which such a display comes about, as a concept 'and in prac tice, and on the way in which ideas are reflected in and thrown up by it. -

Download Entire Issue

Inter Gentes Cover Editorial Team The cover image was taken by Arian Zwegers at Alicia Blimkie Madeleine Macdonald (Associate Editor 2016-2017) (Associate Editor 2016-2017) Yogyakarta, a city on the island of Java in Indonesia. It depicts Wayang Kulit, which is a traditional form of Abbie Buckman Dayeon Min (Associate Editor 2016-2017) (Associate Editor 2014-2015; Senior Editor theatre originated in Java and spread to other parts of 2015-2016; 2016-2017) Southeast Asia. This cultural art form was inscribed in Amélia Couture 2008 on UNESCO’s Representative List of the (Senior Editor 2015-2016) Amelia Philpott Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (originally Emilie de Haas (Associate Editor (Associate Editor 2016-2017) proclaimed in 2003). UNESCO reports that this art 2015-2016; Senior Editor 2016-2017) Kevin Pinkoski form, which uses flat shadow puppets made of leather, Didem Dogar (Senior Editor 2016-2017) is believed to have survived in part because of its (Associate Editor 2015-2016) Maria Rodriguez significance in criticizing social and political issues in Sara Espinal (Associate Editor 2014-2015; 2015-2016) addition to telling stories. We hope that this thematic (Senior Editor 2014-2015; 2015-2016) Shaké Sarkhanian issue contributes to encouraging dialogue on tangible Élodie Fortin (Associate Editor 2015-2016; Editorial Chair and intangible ownership that has impacted people (Associate Editor 2016-2017) 2016-2017) worldwide such as this one. Brianna Gorence Jeelan Syed (Associate Editor 2015-2016; (Executive Editor 2014-2015; 2015-2016) Executive Editor 2016-2017) Anna Wettstein L'image de couverture a été prise par Arian Zwegers à Isabelle Jacovella Rémillard (Associate Editor 2014-2015; Yogyakarta, une ville sur l'île de Java en Indonésie. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (As of 2018)

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (As of 2018) 2018 Art of dry stone walling, knowledge and techniques Croatia – Cyprus – France – Greece – Italy – Slovenia – Spain – Switzerland As-Samer in Jordan Jordan Avalanche risk management Switzerland – Austria Blaudruck/Modrotisk/Kékfestés/Modrotlač, resist block printing Austria – Czechia – and indigo dyeing in Europe Germany – Hungary – Slovakia Bobbin lacemaking in Slovenia Slovenia Celebration in honor of the Budslaŭ icon of Our Lady (Budslaŭ Belarus fest) Chakan, embroidery art in the Republic of Tajikistan Tajikistan Chidaoba, wrestling in Georgia Georgia Dondang Sayang Malaysia Festivity of Las Parrandas in the centre of Cuba Cuba Heritage of Dede Qorqud/Korkyt Ata/Dede Korkut, epic Azerbaijan – culture, folk tales and music Kazakhstan – Turkey Horse and camel Ardhah Oman Hurling Ireland Khon, masked dance drama in Thailand Thailand La Romería (the pilgrimage): ritual cycle of 'La llevada' (the Mexico carrying) of the Virgin of Zapopan Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa, knowledge and China practices concerning life, health and illness prevention and treatment among the Tibetan people in China Međimurska popevka, a folksong from Međimurje Croatia Mooba dance of the Lenje ethnic group of Central Province of Zambia Zambia Mwinoghe, joyous dance Malawi Nativity scene (szopka) tradition in Krakow Poland Picking of iva grass on Ozren mountain Bosnia and Herzegovi na Pottery skills of the women of Sejnane Tunisia Raiho-shin, ritual visits of deities in masks -

Les Premiers Hommes: Conte Pour Enfant D'origine Malgache PDF TÉLÉCHARGER

Les premiers hommes: Conte pour enfant d'origine Malgache PDF TÉLÉCHARGER TÉLÉCHARGER LIRE ENGLISH VERSION DOWNLOAD READ Les premiers hommes: Conte pour enfant d'origine Malgache PDF TÉLÉCHARGER Description Il n'y avait qu'un seul homme sur terre et il ne lui manquait de rien jusque que Dieu lui envoie des amies, après tous changent Continuons cette genèse de la langue malgache. La phrase malgache « mihinan-kanina aho » a pour origine trois langues ; MIHIN hébreu, AKAL assyrien et. 29 avr. 2017 . Pour le monde africain, l'enjeu est géopolitique. de son histoire falsifiée et de la manipulation médiatique : guerres, pauvreté, . Les origines des Malgaches paraissent simples au premier abord. Sur le continent on trouve Mwana-Mambo chez les hommes fils de chefs et doivent assumer la régence. C'est la raison pour laquelle, continue la légende, on se tourne vers l'Est . La légende doit son origine à la tentative d'expliquer les différences d'état . D'après d'autres, Dieu donna aux premiers hommes d'avoir à choisir d'habiter sans enfants . dans le (9) Conte analogue dans A. DAHLE et J. SIMS, Anganon'ny Ntaolo. laisser partir et s'enfuir ses enfants ? Quelle politique . sur l'histoire de la « colonisation » et la prise . frontaient sur l'origine des Malgaches : la . giques pour déterminer les premiers ancêtres . d'hommes, possédaient des ancêtres indo-. Un des premiers essais de composition poétique et musicale dans . “L'enfant qui s'enquiert de la mort, un conte malgache entre écrit et oral”, in .. “L'Arche de Noé dans l'Océan Indien, un thème d'origine de l'homme dans les contes .