The Naxos Papers, Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations Abstract There are suggestions that King Alfred’s legendary literary renaissance may have been a reaction to the efforts of the neighbouring kingdom of Mercia. According to Asser, Alfred assembled a group of literary scholars from this rival Mercian tradition at his court. But it is not clear what early literary activities these scholars could have been involved in to justify their pre-Alfredian reputation. This article tries to outline the historical and literary evidence for early Mercian text production, and the importance of this ‘other’ early literary corpus. What is our current knowledge of Mercian text production and the political and literary relationship of Mercia with Canterbury? What was the relationship of Alfred’s educational movement with its Mercian forerunner? Why is modern scholarship better informed about Alfred’s movement than any Mercian rival culture? If our current knowledge of this area is insufficient for the writing of a literary history of Mercia, a provisional list of texts and bibliography, published electronically for convenient updating, may prove useful in the meantime. Alfredian evidence for Mercian literary culture That King Alfred claims to have initiated an educational Renaissance is well known. Alfredian writings acknowledge a marked decline in learning and scholarship, at least in terms of Latin text composition and manuscript production, and at least in Wessex (Lapidge 1996, 436-439). But the same texts also suggest the existence of -

“Sitte Ge Sigewif, Sigað to Eorðe”: Settling the Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm Within Its Christian Manuscript Context

https://doi.org/10.7592/Incantatio2018_7_O’Connor “SITTE GE SIGEWIF, SIGAÐ TO EORÐE”: SETTLING THE ANGLO-SAXON BEE CHARM WITHIN ITS CHRISTIAN MANUSCRIPT CONTEXT. Patricia O’Connor The Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm is one of a select number of Old English charms that were previously described as being “strange companions” to the Old English Bede (Grant 5). Written in the outer margin of page 182 of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 41 (CCCC41), the Bee Charm accompanies a passage from Chapter XVII of Book III of the Old English Bede which narrates the consecration of a monastic site. Curiously, however, the Bee Charm’s connection to this passage of the Old English Bede and its influence on our reading of this important text has hitherto been inadequately addressed. Consequently, the objective of this article is to critically reconsider the Bee Charm within its immediate manuscript context and to highlight and evaluate the correspondences shared between the Anglo-Saxon charm and the adjacent passage of the Old English Bede. This codi- cological reassessment seeks to present a new interpretation of the Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm through encouraging a more inclusive reading experience of CCCC41, which incorporates both the margins and the central text. In doing so, this study endeavours to offer significant insights into the function of theBee Charm within Anglo-Saxon society and to contribute to our understanding of how these charms were perceived and circulated within late Anglo-Saxon England. Keywords: Marginalia, Bees, Old English Bede, New Philology, Old English Literature, Palaeography, Scribal Practices. The Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm is one of a number of interesting texts that were inserted anonymously into the margins of a well-known manuscript witness of the Old English Bede. -

Gerald Dyson

CONTEXTS FOR PASTORAL CARE: ANGLO-SAXON PRIESTS AND PRIESTLY BOOKS, C. 900–1100 Gerald P. Dyson PhD University of York History March 2016 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination and analysis of the books needed by and available to Anglo-Saxon priests for the provision of pastoral care in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Anglo-Saxon priests are a group that has not previously been studied as such due to the scattered and difficult nature of the evidence. By synthesizing previous scholarly work on the secular clergy, pastoral care, and priests’ books, this thesis aims to demonstrate how priestly manuscripts can be used to inform our understanding of the practice of pastoral care in Anglo-Saxon England. In the first section of this thesis (Chapters 2–4), I will discuss the context of priestly ministry in England in the tenth and eleventh centuries before arguing that the availability of a certain set of pastoral texts prescribed for priests by early medieval bishops was vital to the provision of pastoral care. Additionally, I assert that Anglo- Saxon priests in general had access to the necessary books through means such as episcopal provision and aristocratic patronage and were sufficiently literate to use these texts. The second section (Chapters 5–7) is divided according to different types of priestly texts and through both documentary evidence and case studies of specific manuscripts, I contend that the analysis of individual priests’ books clarifies our view of pastoral provision and that these books are under-utilized resources in scholars’ attempts to better understand contemporary pastoral care. -

Downloaded1 from Brill.Com09/28/2021 08:16:42AM Via Free Access 542 Rauer

Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 77 (�0�7) 54�–558 brill.com/abag Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations Christine Rauer University of St Andrews, UK [email protected] Abstract There are suggestions that King Alfred’s legendary literary renaissance may have been a reaction to the efforts of the neighbouring kingdom of Mercia. According to Asser, Alfred assembled a group of literary scholars from this rival Mercian tradition at his court. But it is not clear what early literary activities these scholars could have been involved in to justify their pre-Alfredian reputation. This article tries to outline the historical and literary evidence for early Mercian text production, and the impor- tance of this ‘other’ early literary corpus. What is our current knowledge of Mercian text production and the political and literary relationship of Mercia with Canterbury? What was the relationship of Alfred’s educational movement with its Mercian forerun- ner? Why is modern scholarship better informed about Alfred’s movement than any Mercian rival culture? If our current knowledge of this area is insufficient for the writ- ing of a literary history of Mercia, a provisional list of texts and bibliography, published electronically for convenient updating, may prove useful in the meantime. Keywords Old English literature – Anglo-Saxon history – ethnicity – borders – Old English dialects – text production – King Alfred – authorship * An earlier version of this paper was presented to the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists (ISAS, Glasgow, 2015). I am grateful for the feedback received from members of ISAS and the Vereniging van Oudgermanisten. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���7 | doi �0.��63/�87567�9-��34009Downloaded� from Brill.com09/28/2021 08:16:42AM via free access 542 Rauer 1 Alfredian Evidence for Mercian Literary Culture That King Alfred claims to have initiated an educational Renaissance is well known. -

Iron-Clad Evidence in Early Mediaeval Dialectology: Old English Ïsern, Ïsen, and Ïren

Iron-Clad Evidence in Early Mediaeval Dialectology: Old English ïsern, ïsen, and ïren Nearly a quarter of a century ago, Helmut Gneuss argued that the standard variety of late West Saxon Old English originated at Winchester. In discussing his methodology, he predicted the direction of future research. In the future, I think, one may confidently expect significant findings … from the study of word usage and word geography; the project of a new, comprehensive Old English dictionary, to be based on computer-made concordances of all Old English texts … is a decisive step in this direction.1 Gneuss identifies two major developments in philological and linguistic research: the exploration of ‘word usage and word geography’ and the adoption of new research methodologies and techniques. Both of these issues are relevant to the subject of this paper, an examination of the usage and geographical distribution of the three forms of the Old English word for ‘iron’: ïsern, ïsen, and ïren. The aim of the study is to provide a contribution to the canon of new dialect criteria which will become available as a result of the increasing use of electronic text searches and which may, once it has grown large enough, provide a new basis for our understanding of the Old English dialects. Although a number of early studies have looked at word dialectology in Old English, the greatest body of evidence in the philological canon is phonological and morphological.2 However, since Gneuss’ prediction, a number of tools have become or are becoming available which are set to place a new emphasis in research on the lexical history of early English. -

Liturgy As History: the Origins of the Exeter Martyrology

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Liturgy as history: the origins of the Exeter martyrology AUTHORS Hamilton, S JOURNAL Traditio: Studies in Ancient and Medieval History, Thought, and Religion DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 November 2019 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/39448 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 Liturgy as History: The Origins of the Exeter Martyrology Sarah Hamilton, University of Exeter Abstract Through an Anglo-Norman case study, this article highlights the value of normative liturgical material for scholars interested in the role which saints’ cults played in the history and identity of religious communities. The records of Anglo-Saxon cults are largely the work of Anglo-Norman monks. Historians exploring why this was the case have therefore concentrated upon hagiographical texts about individual Anglo-Saxon saints composed in and for monastic communities in the post-Conquest period. This article shifts the focus away from the monastic to those secular clerical communities which did not commission specific accounts, and away from individual cults, to uncover the potential of historical martyrologies for showing how such secular communities remembered and understood their own past through the cult of saints. Exeter Cathedral Library, Ms 3518, is a copy of the martyrology by the ninth-century Frankish monk, Usuard of Saint-Germain-des-Prés , written in and for Exeter cathedral’s canons in the mid-twelfth century. -

A Paradise Full of Monsters: India in the Old English Imagination

LATCH: A Journal for the Study of the Literary Vol. 1 Artifact in Theory, Culture, or History (2008) A Paradise Full of Monsters: India in the Old English Imagination Mark Bradshaw Busbee Florida Gulf Coast University Abstract Between the ninth and the twelfth centuries in England, the idea of India began to figure into Anglo-Saxon statecraft, religion, and literature. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that in 883, Alfred the Great promised to send emissaries to India; a sermon preached by the Anglo-Saxon priest Ælfric in the tenth century tells about the passion of Saint Thomas and his trials and eventual death in India; and Old English translations of Alexander’s Letter to Aristotle and The Wonders of the East describe the amazing riches, unusual animals, and monstrous people found in India. Scholars applying post- colonial theory to these texts see them as essentially racist. This essay argues that such reductive readings miss the deep complexities in how Anglo-Saxons imagined India or what those fantastic ideas might reveal. The many notable ambivalences appearing in descriptions of India and its people show that Anglo- Saxons regarded India as an imaginative space where fears, hopes, and desires might be entertained freely. Rather than support the notion that the Anglo-Saxon mind was inherently racist, these texts, in their expressions of fear and fascination, reveal a willingness to engage and understand a mysterious Other. Keywords India, Old English, Anglo-Saxon, manuscripts, monsters, Wonders of the East, The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle, Cotton Tiberius, Cotton Vitellius, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ælfric, Alfred the Great Old English manuscripts dating from the late ninth through the early twelfth centuries contain what may be the most neglected 51 Mark Bradshaw Busbee A Paradise Full of Monsters: pp. -

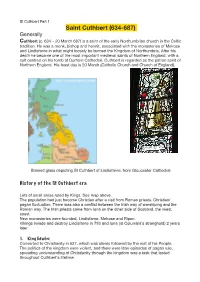

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (C

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) is a saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria. After his death he became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northern England. His feast day is 20 March (Catholic Church and Church of England), Stained glass depicting St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, from Gloucester Cathedral History of the St Cuthbert era Lots of small areas ruled by Kings. See map above. The population had just become Christian after a visit from Roman priests. Christian/ pagan fluctuation. There was also a conflict between the Irish way of worshiping and the Roman way. The Irish priests came from Iona on the other side of Scotland, the /west coast. New monasteries were founded, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Ripon. Vikings invade and destroy Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona (st Columbia’s stronghold) 2 years later. 1. King Edwin: Converted to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by the rest of his People. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-73908-5 - Monastic Life in Anglo-Saxon England, c. 600–900 Sarah Foot Index More information Index Aachen, council at in 816/17 13(n29), 35, 42, 45, Æthelbald, king of the Mercians 91, 92, 127, 60 128, 131(n241), 188, 243, 245, 326 Abba, Kentish reeve, will of 136(n269), 150, 164, Æthelberht, bishop of Hexham 292 317 Æthelberht, king of Kent 62, 77, 89 abbesses 39, 71, 139, 151, 166, 306 baptism of 62, 297--8 Abbo of Fleury 116 Æthelburh, abbess of Brie 150 abbots 39, 43, 46, 71, 82, 131, 166, 170, 185, Æthelburh, abbess of Ely 167 289 Æthelburh, daughter of comes Alfred and abbess and postulants 155, 163 of Fladbury, Twyning and Withington 95, appointment of 55, 132, 274 206, 279, 318 election of 167--8 Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred 83, 324 laymen as 58, 128, 130, 132, 159, 169 Æthelgifu, daughter of King Alfred 83, 164, priests as 176--9, 265, 272 317 Abingdon, Oxon. 13, 75, 128, 237 Æthelheah, abbot of Icanho 277 Acca, abbot and bishop of Hexham 203, 259 Æthelheard, archbishop of Canterbury 61, 134 ad Repingas 268, 272, 275 Æthelhild, abbess 106, 108 Adamnan, abbot 159 minster of 108, 181, 310, 325--6 Admonitio generalis 60, 161 Æthelred ‘the Unready’ 330 Æbba, mother of St Leoba 143 Æthelred, ealdorman of the Mercians 83, 324 Æbbe, abbess of Coldingham 325 Æthelred, king of the Mercians 264, 272--3, 275 Ædde and Æona, singers 203 Æthelric, son of ealdorman Æthelmund 84, 316 Aedeluald, bishop of Lichfield 209 Æthelstan, king of the West Saxons 12, 120, Ælberht, archbishop of York 229, 346 242, -

Towns in Anglo-Saxon England

From Dark Earth to Domesday: Towns in Anglo-Saxon England Author: David Crane Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:104070 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of History FROM DARK EARTH TO DOMESDAY: TOWNS IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND a dissertation by David D. Crane submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2014 © copyright by DAVID DANIEL CRANE 2014 Dissertation Abstract From Dark Earth to Domesday: Towns in Anglo-Saxon England David D. Crane Robin Fleming, Advisor 2014 The towns that the Norman invaders found in England in 1066 had far longer and far more complex histories than have often been conveyed in the historiography of the Anglo-Saxon period. This lack of depth is not surprising, however, as the study of the towns of Anglo-Saxon England has long been complicated by a dearth of textual sources and by the work of influential historians who have measured the urban status of Anglo-Saxon settlements using the attributes of late medieval towns as their gage. These factors have led to a schism amongst historian regarding when the first towns developed in Anglo-Saxon England and about which historical development marks the beginning of the continuous history of the English towns. This dissertation endeavors to apply new evidence and new methodologies to questions related to the development, status, and nature of Anglo-Saxon urban communities in order to provide a greater insight into their origins and their evolutionary trajectories. -

The Synthesis of Anglo-Saxon and Christian Traditions in the Old English Judith

THE SYNTHESIS OF ANGLO-SAXON AND CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS IN THE OLD ENGLISH JUDITH SARAH E. EAKIN Bachelor of Arts in English Illinois State University December 2008 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSTIY December 2013 We hereby approve this thesis for SARAH E. EAKIN Candidate for the Master of Arts in English degree for the Department of ENGLISH and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies by _________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Stella Singer _____________________________________________ Department & Date _________________________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. James Marino _____________________________________________ Department & Date _________________________________________________________________ Thesis Committee Member, Dr. David Lardner _____________________________________________ Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense: November 26, 2013 Dedicated to Joseph Zilkowski THE SYNTHESIS OF ANGLO-SAXON AND CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS IN THE OLD ENGLISH JUDITH SARAH E. EAKIN ABSTRACT The Anglo-Saxons were a people who took great pride in their heritage and culture. However, they faced various challenges in preserving the pagan traditions of their Nordic ancestors while being heavily influenced by Christianity. Many Anglo- Saxon texts demonstrate these cultural challenges, but the Book of Judith, found in the Nowell-Codex, attempts to unify the two -

Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture

139 4 Assembling and reshaping Christianity in the Lives of St Cuthbert and Lindisfarne Gospels In the previous chapter on the Franks Casket, I started to think about the way in which a thing might act as an assembly, gather- ing diverse elements into a distinct whole, and argued that organic whalebone plays an ongoing role, across time, in this assemblage. This chapter begins by moving the focus from an animal body (the whale) to a human (saintly) body. While saints, in early medieval Christian thought, might be understood as special and powerful kinds of human being – closer to God and his angels in the heavenly hierarchy and capable of interceding between the divine kingdom and the fallen world of mankind – they were certainly not abstract otherworldly spirits. Saints were embodied beings, both in life and after death, when they remained physically present and accessible through their relics, whether a bone, a lock of hair, a fingernail, textiles, a preaching cross, a comb, a shoe. As such, their miracu- lous healing powers could be received by ordinary men, women and children by sight, sound, touch, even smell or taste. Given that they did not simply exist ‘up there’ in heaven but maintained an embodied presence on earth, early medieval saints came to be asso- ciated with very particular places, peoples and landscapes, with built and natural environments, with certain body parts, materi- als, artefacts, sometimes animals. Of the earliest English saints, St Cuthbert is probably one of, if not the, best known and even today remains inextricably linked to the north-east of the country, especially the Holy Island of Lindisfarne and its flora and fauna.