ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON at PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON AT PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018 Peabody Conductors' Orchestra Tuesday, November 27, 2018 Peabody Symphony Orchestra Saturday, December 1, 2018 STEINWAY. YAMAHA. [ YOUR NAME HERE ] With your gi to the Piano Excellence Fund at Peabody, you can add your name to the quality instruments our outstanding faculty and students use for practice and performance every day. The Piano Department at Peabody has a long tradition of excellence dating back to the days of Arthur Friedheim, a student of Franz Liszt, and continuing to this day, with a faculty of world-renowned artists including the eminent Leon Fleisher, who can trace his pedagogical lineage back to Beethoven. Peabody piano students have won major prizes in such international competitions as the Busoni, Van Cliburn, Naumburg, Queen Elisabeth, and Tchaikovsky, and enjoy global careers as performers and teachers. The Piano Excellence Fund was created to support this legacy of excellence by funding the needed replacement of more than 65 pianos and the ongoing maintenance and upkeep of nearly 200 pianos on stages and in classrooms and practice rooms across campus. To learn more about naming a piano and other creative ways to support the Peabody Institute, contact: Jessica Preiss Lunken, Associate Dean for External Affairs [email protected] • 667-208-6550 Welcome back to Peabody and the Miriam A. Friedberg Concert Hall. This month’s programs show o a remarkable array of musical styles and genres especially as related to Peabody’s newly imagined ensembles curriculum, which has evolved as part of creating the Conservatory’s groundbreaking Breakthrough Curriculum. -

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) S Elise Braun Barnett

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) s Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections Elise Braun Barnett Introduction Otto Deri often used to discuss programs for piano recitals with me. More than once he expressed surprise that the late piano compositions of Liszt were performed only rarely. He recommended their serious study since, as he pointed out, in these pieces Liszt's conception of melody, rhythm, and harmony are quite novel and anticipate Debussy, Ravel, and Bartok. These discussions came to mind when a friend of mine, Mrs. Oscar Kanner, a relative of Moriz Rosenthal,! showed me an article by the pianist entitled "Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections," which had appeared in a 1911 issue of the journal Die Musik,2 and also a handwritten, unpublished autobiography written in New York during the last years of Rosenthal's life, 1940 to 1946. Rosenthal's concerts in Europe and America are still remembered by the older generation. His musical conceptions, emotions projected on the piano with an amazing technique, remain an unforgettable experience. He is also remembered as having been highly cultivated, witty, and sometimes sar- castic. His skill in writing is less known, but his autobiography and essays reveal a most refined, fluent, and vivid German style. He is able to conjure up the "golden days," when unity of form and content was appreciated. It is my hope that the following annotated translation of Rosenthal's article will provide a worthy tribute to the memory of Otto Deri. Translation In October of 1876, as a youngster of thirteen, I played for Franz Liszt during one of his frequent visits to the Schottenhof in Vienna,3 and I was admitted to his much envied entourage as perhaps the youngest of his disciples. -

111036-37 Bk Fledermaus

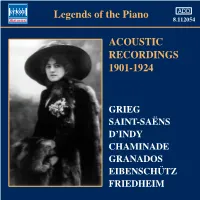

112054 bk Legends EU 4/5/10 08:33 Page 5 Princess Marcelina Czartoryska. Here, Janotha plays For Liszt and pedagogues like Theodor Leschetizky and pupil, Friedheim became Liszt’s teaching assistant, Friedheim, born in St Petersburg. Twice offered the ADD from Chopin’s own manuscript of a Bach-inspired Anton Rubinstein, the piano was a one-piece orchestra, personal secretary, and confidant. He was probably the directorship of the New York Philharmonic, honoured at Legends of the Piano youthful work (with Chopin’s handwritten notations) the synthesizer of its time, to be “conducted” for a full closest student of all to Liszt, both in piano technique the Taft White House and the courts of Europe, 8.112054 given her by the princess. Even in an age of range of colour and effect through rubato, individual (the sweeping “grand manner”) and general Friedheim was banned from the concert stage and eccentricity, Mme Janotha stood apart: as Mark accentuations, and pedal artistry. In the twentieth temperament (intensely philosophical, with spiritual reduced overnight to playing for the silent movies and Hambourg observed, her concerts were always adorned century, these two approaches survived in the mellow overtones), even sharing a physical resemblance. the vaudeville circuit. His combustible reading of by “a magnificent black cat, without which she declared singing line of Artur Rubinstein, protégé of Joseph “Friedheim’s recital,” to one newspaper critic in 1922, Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, says a 1915 review in that it was impossible for her to play a single note, and Joachim, the great violinist and intimate of Brahms and “was more of a séance”. -

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: the Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: The Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility Peter Phillips A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Historical Performance Unit Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2016 i Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Declaration I declare that the research presented in this thesis is my own original work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted to any other institution for the award of a higher degree. All illustrations, graphs, drawings and photographs are by the author, unless otherwise cited. Signed: _______________________ Date: 2___________nd July 2017 Peter Phillips © Peter Phillips 2017 Permanent email address: [email protected] ii Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Acknowledgements A pivotal person in this research project was Professor Neal Peres Da Costa, who encouraged me to undertake a doctorate, and as my main supervisor, provided considerable and insightful guidance while ensuring I presented this thesis in my own way. Professor Anna Reid, my other supervisor, also gave me significant help and support, sometimes just when I absolutely needed it. The guidance from both my supervisors has been invaluable, and I sincerely thank them. One of the greatest pleasures during the course of this research project has been the number of generous people who have provided indispensable help. From a musical point of view, my colleague Glenn Amer spent countless hours helping me record piano rolls, sharing his incredible knowledge and musical skills that often threw new light on a particular work or pianist. -

A Study of the Personality of Franz Liszt with Special

· ~ I (; A STUDY OF THE PERSONALITY OF FRANZ LISZT WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE CONTRADICTIONS IN HIS NATURE Submitted for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Rhodes University by BERYL EILEEN ENSOR-SMITH January 1984 (ii} CONTENTS Chapter I Background Page 1 CAREER CONFLICTS Chapter II Pianist/Composer Page 17 Chapter III Showman/Serious Musician Page 33 PERSONALITY CONFLICTS Chapter IV Ambiguity in Liszt's Relationships - Personal and Spiritual Page 77 Chapter V Finally- Resignation ... Dogged Perseverance . .. Hopeful Optimism Page 116 ----oooOooo---- (iii) ILLUSTRATIONS Liszt, the Child At the end of Chapter I Liszt, the Young Man At the end of Chapter II Liszt, the performer At the end of Chapter III Liszt, Strength or Arrogance? At the end of Chapter IV L'Abbe Liszt Liszt, Growing Older Liszt, the Old Man At the end of Chapter V Liszt, from the last photographs Liszt . .. The End ----oooOooo---- A STUDY OF THE PERSONALITY OF FRANZ LISZT WITH SPECIAL r~FERENCE TO THE CONTRADICTIONS IN HIS NATURE Chapter I BACKGROUND "The man who appears unable to find peace there can be no doubt that we have here to deal with the extraordinary, multiply-moved mind as well as with a mind influencing others. His own life is to be found in his music." (Robert Schumann 19.4) Even the birth of Franz Liszt was one of duality - he was a child of the borderline between Austria and Hungary. His birthplace, even though near Vienna, was on the confines of the civilized world and not far removed from the dominions of the Turk. -

Piano Mannerisms, Tradition and the Golden Ratio In

Performing mannerisms by ten celebrated pianists born in the 19th century taken from reproducing piano roll recordings of the Chopin Nocturne in F sharp major opus 15 no. 2; the mysterious tradition of the Klindworth D natural in the Liszt Sonata; and some astonishing discoveries about the golden ratio in the Chopin Etudes and the Liszt Sonata. /( ( 00 3 # 7! !<=>;=?8:@A B($*0(C-#0( !)(** !5DE DK B<:6E<KG9E< !=<66 ABN 30 628 090 446 165/137 Victoria Street, Ashfield NSW 2131 Tel +61 2 9799 4226 Email [email protected] Designed and printed in Australia by Wensleydale Press, Ashfield 1;LK=8@FM N /<=9=G 19=M<= HIIJ All rights reserved. This book is copyright. EXcept as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. "*3$ OJPQIQOJJRSJTQOQP This publication is sold and distributed on the understanding that the publisher and the author cannot guarantee that the contents of this publication are accurate, reliable, complete or up to date; they do not take responsibility for errors or missing information; they do not take responsibility for any loss or damage that happens as a result of using or relying on the contents of this publication; and they are not giving advice in this publication. 2 1%$,($,* 1. Performing mannerisms by ten celebrated pianists born in the 19th century taken from reproducing piano roll recordings of the Chopin Nocturne in F sharp major opus 15 no. -

Changing Chopin

CHANGING CHOPIN: POSTHUMOUS VARIANTS AND PERFORMANCE APPROACHES By Ho Sze-Hwei Grace A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Philosophy Department of Music University of Birmingham Birmingham, United Kingdom September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to examine Chopin’s own style of playing and to trace some of the approaches taken by 19th century pianists in interpreting Chopin. In doing so, the study hopes to challenge our assumptions about the sacrosanct nature of the text, while offering possibilities for performance. Through examining the accounts of Chopin’s playing and teaching as well as the customs that would have been familiar to him, this study offers a glimpse of the practices that is today often neglected or simply relegated to the annals of ‘historical performance practice’. Special attention is also given to exploring the aspects of Chopin’s style that might pose particular problems of interpretation, such as rubato, tempo and pedalling. In the final analysis, perhaps it is not the early interpreters who represent a ‘radical’ break from Chopin’s aesthetic, but we modern interpreters, with our more rigorous standards and stricter notion of ‘fidelity to the score’. -

In the Preface to the 1865 Edition of His Transcriptions Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Pace, I. (2006). Conventions, Genres, Practices in the Performance of Liszt’s Piano Music. Liszt Society Journal, 31, pp. 70-103. City Research Online Original citation: Pace, I. (2006). Conventions, Genres, Practices in the Performance of Liszt’s Piano Music. Liszt Society Journal, 31, pp. 70-103. Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/5296/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. CONVENTIONS, GENRES, PRACTICES IN THE PERFORMANCE OF LISZT’S PIANO MUSIC Ian Pace To Patrícia Sucena Almeida Performance Practice as an Area of Study in the Music of Liszt The very existence of performance practice as a field of scholarly research, with implications for actual performers and performances, remains a controversial area, nowhere more so than when such study involves the nineteenth-century, the period which forms the core of the standard repertoire for many musicians of all types. -

CHOPIN: the MAN and HIS MUSIC Author: James Huneker

CHOPIN: THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC Author: James Huneker TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I.--THE MAN. I. POLAND:--YOUTHFUL IDEALS II. PARIS:--IN THE MAELSTROM III. ENGLAND, SCOTLAND AND FERE LA CHAISE IV. THE ARTIST V. POET AND PSYCHOLOGIST PART II.--HIS MUSIC. VI. THE STUDIES:--TITANIC EXPERIMENTS VII. MOODS IN MINIATURE: THE PRELUDES VIII. IMPROMPTUS AND VALSES IX. NIGHT AND ITS MELANCHOLY MYSTERIES: THE NOCTURNES X. THE BALLADES: FAERY DRAMAS XI. CLASSICAL CURRENTS XII. THE POLONAISES: HEROIC HYMNS OF BATTLE XIII. MAZURKAS: DANCES OF THE SOUL XIV. CHOPIN THE CONQUEROR BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS BY JAMES HUNEKER PART I.--THE MAN I. POLAND:--YOUTHFUL IDEALS Gustave Flaubert, pessimist and master of cadenced lyric prose, urged young writers to lead ascetic lives that in their art they might be violent. Chopin's violence was psychic, a travailing and groaning of the spirit; the bright roughness of adventure was missing from his quotidian existence. The tragedy was within. One recalls Maurice Maeterlinck: "Whereas most of our life is passed far from blood, cries and swords, and the tears of men have become silent, invisible and almost spiritual." Chopin went from Poland to France--from Warsaw to Paris--where, finally, he was borne to his grave in Pere la Chaise. He lived, loved and died; and not for him were the perils, prizes and fascinations of a hero's career. He fought his battles within the walls of his soul- -we may note and enjoy them in his music. His outward state was not niggardly of incident though his inner life was richer, nourished as it was in the silence and the profound unrest of a being that irritably resented every intrusion. -

REFERENCE USE ONLY D OQD1 45L400 I43 Fi THE

This Volume is for REFERENCE USE ONLY D OQD1 45L400 I43 fi THE OF % ^ ^ THE UNITE$p'gTATES. VOLUME VIII. Season of 1890-1891. .^ BY n H. WILSON, BOSTON. PRICE, ONE BY Street, Boston, Mass, Back numbers are for sale. *Wrt volumes, bound in boards, $6,00. i BY CHA^ttB^ HAMILTON, (ijable of (gon tents. PREFACE ; . Pa#e 3 * ** TABLE OP CONTENTS . 4 " CITIES . 5-9S GENEKAL RECORD BY .] MISCELLANEOUS RECORD " 98-101 " MUSIC TEACHERS' NATIONAL ASSOCIATION . 102 NEW " AMERICAN COMPOSITIONS ., 103 " AMERICAN MUSIC PREFORMED ABROA D . 104 PUBLISHED AMERICAN WORKS - 105 ^ STANDARD CHORAL WORKS PK UFO RME.D SOLOISTS " 100-107 IMPORTANT NEW WORKS ...... u 108 RETROSPECT " 109-1U j " A DIRECTORY OF SINGERS, PLAYERS <fe JTR ACH 1C Its H5-11S ADDENDA i. "119 " INDEX OF TITLES '. 123-140 INDEX OF ADVERTISERS :~ ARTHUK P. SCHMIDT, PUBLISHER . , . 2d Page<iw^r " CINCINNATI COLLEGE OF Music . * . .3d u MASON & HAMHN PIANOS AND ORGANS . - . 4th KNABE PIANOS I*a#e 120 F. A. OLIVER, VIOLINS 121 CH. C. PARKYN, MUSICAL AGENT .... "121 NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY .... fck 122 &. SCHIRMKR, PUBLISHER , "HI BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA .... tk 142 M. STEINKHT & SONS PIANO COMPANY . "1^3 NATIONAL CONSERVATORY ...... ** 144-143 u H. B. STRVKNS fc Co., PUBLISHWKS 146 kk HENRY F. MILLER & SONS PIANO COMPANY . 147 " OLIVER DITSON COMPANY, PUBLISHERS . 14S CHICKBHING & SONS PIANOS ' HO CHICKERING HALLS 4< 150 " Bos i ON FESTIVAL ORCHKSTRA 151 NOVKLLO, EWJfiR *fe Co., PUH ALBANY, N. Y. SCHUBERT CLUB. Sixth Season. Male Chorus of 44. Bleecker Hall Conductor, AKTHUR MEISS. Dec. 4. "Gipsy Life," Schumann; "Love and Wine," Men- delssohn; Vesper Hymn, Beethoven; "By the Sea," Schubert; "Night in the Forest," Speidel; "When two fond Hearts must " "Battle from sever,*' Schwalm ; Marguerita," Jensen; Hymn" "Bienzi," Wagner Soloist, Mine.