In the Preface to the 1865 Edition of His Transcriptions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor

Minnesota Musicians ofthe Cultured Generation Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor The appeal ofAmerica 1) Early life & arrival in Minneapolis 2) Work in Minneapolis 3) Into the out-of-doors 4) Death & appraisal Robert Tallant Laudon Professor Emeritus ofMusicology University ofMinnesota 924 - 18th Ave. SE Minneapolis, Minnesota 55414 (612) 331-2710 [email protected] 2002 Heinrich Hoevel (Courtesy The Minnesota Historical Society) Heinrich Hoevel Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor A veritable barrage ofinformation made the New World seem like an answer to all the yearnings ofpeople ofthe various German States and Principalities particularly after the revolution of 1848 failed and the populace seemed condemned to a life of servitude under the nobility and the military. Many of the Forty-Eighters-Achtundvierziger-hoped for a better life in the New World and began a monumental migration. The extraordinary influx of German immigrants into America included a goodly number ofgifted artists, musicians and thinkers who enriched our lives.! Heinrich Heine, the poet and liberal thinker sounded the call in 1851. Dieses ist Amerika! This, this is America! Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Nicht die heutige, die schon Not the present-day already Europaisieret abwelkt. -- Faded Europeanized one. Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Wie sie Christoval Kolumbus Such as Christopher Columbus Aus dem Ozean hervorzog. Drew from out the depths of -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON at PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON AT PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018 Peabody Conductors' Orchestra Tuesday, November 27, 2018 Peabody Symphony Orchestra Saturday, December 1, 2018 STEINWAY. YAMAHA. [ YOUR NAME HERE ] With your gi to the Piano Excellence Fund at Peabody, you can add your name to the quality instruments our outstanding faculty and students use for practice and performance every day. The Piano Department at Peabody has a long tradition of excellence dating back to the days of Arthur Friedheim, a student of Franz Liszt, and continuing to this day, with a faculty of world-renowned artists including the eminent Leon Fleisher, who can trace his pedagogical lineage back to Beethoven. Peabody piano students have won major prizes in such international competitions as the Busoni, Van Cliburn, Naumburg, Queen Elisabeth, and Tchaikovsky, and enjoy global careers as performers and teachers. The Piano Excellence Fund was created to support this legacy of excellence by funding the needed replacement of more than 65 pianos and the ongoing maintenance and upkeep of nearly 200 pianos on stages and in classrooms and practice rooms across campus. To learn more about naming a piano and other creative ways to support the Peabody Institute, contact: Jessica Preiss Lunken, Associate Dean for External Affairs [email protected] • 667-208-6550 Welcome back to Peabody and the Miriam A. Friedberg Concert Hall. This month’s programs show o a remarkable array of musical styles and genres especially as related to Peabody’s newly imagined ensembles curriculum, which has evolved as part of creating the Conservatory’s groundbreaking Breakthrough Curriculum. -

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) S Elise Braun Barnett

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) s Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections Elise Braun Barnett Introduction Otto Deri often used to discuss programs for piano recitals with me. More than once he expressed surprise that the late piano compositions of Liszt were performed only rarely. He recommended their serious study since, as he pointed out, in these pieces Liszt's conception of melody, rhythm, and harmony are quite novel and anticipate Debussy, Ravel, and Bartok. These discussions came to mind when a friend of mine, Mrs. Oscar Kanner, a relative of Moriz Rosenthal,! showed me an article by the pianist entitled "Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections," which had appeared in a 1911 issue of the journal Die Musik,2 and also a handwritten, unpublished autobiography written in New York during the last years of Rosenthal's life, 1940 to 1946. Rosenthal's concerts in Europe and America are still remembered by the older generation. His musical conceptions, emotions projected on the piano with an amazing technique, remain an unforgettable experience. He is also remembered as having been highly cultivated, witty, and sometimes sar- castic. His skill in writing is less known, but his autobiography and essays reveal a most refined, fluent, and vivid German style. He is able to conjure up the "golden days," when unity of form and content was appreciated. It is my hope that the following annotated translation of Rosenthal's article will provide a worthy tribute to the memory of Otto Deri. Translation In October of 1876, as a youngster of thirteen, I played for Franz Liszt during one of his frequent visits to the Schottenhof in Vienna,3 and I was admitted to his much envied entourage as perhaps the youngest of his disciples. -

Amy Fay and Her Teachers in Germany

AMY FAY AND HER TEACHERS IN GERMANY A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree The University of Memphis Judith Pfeiffer May 2008 UMI Number: 3310124 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3310124 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Judith Pfeiffer entitled "Amy Fay and her Teachers in Germany." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts with a major in Music. Gilbert, M.M. ijor Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jatiet K. Page, Ph.D. ip LAX'.~MedA, Kamran Ince, D.M.A. U^ andal Rushing, D.M,Ar Accepted for the Council: V^ UjMlkriJidk KarenlD. Weddle-West, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate Programs ABSTRACT Pfeiffer, Judith. DMA. The University of Memphis. -

The a Lis Auth Szt P Hen Pian Ntic No T Cho Trad Opin Diti N an on Nd

THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 1 2 THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION 3 4 THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 5 Published in 2008 by Wensleydale Press ABN 30 628 090 446 165/137 Victoria Street, Ashfield NSW 2131 Tel +61 2 9799 4226 Email [email protected] Designed and printed in Australia by Wensleydale Press, Ashfield Copyright © Gerard Carter 2008 All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. ISBN 978-0-9805441-2-1 This publication is sold and distributed on the understanding that the publisher and the author cannot guarantee that the contents of this publication are accurate, reliable, complete or up to date; they do not take responsibility for any loss or damage that happens as a result of using or relying on the contents of this publication and they are not giving advice in this publication. 6 7 8 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ... 11 Chapter 2: Chopin and Liszt as composers ...19 Chapter 3: Chopin and Liszt as pianists and teachers ... 29 Chapter 4: Chopin tradition through Mikuli ... 55 Chapter 5: Liszt tradition through Stavenhagen and Kellermann .. -

October 1926) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 10-1-1926 Volume 44, Number 10 (October 1926) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 44, Number 10 (October 1926)." , (1926). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/739 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 MUSIC STUDY EXALTS LIFE MVSIC *dte ETVDE MAG A Z INE Price 25 Cents OCTOBER 1926 $2.00 a Year BEETHOVEN DISCOVERING HIS DEAFNESS Special Enlarged Issue ^ A Remarkable Master Lessonon Beethoven’s “Sonata Pathetique” by the Great Pianist, Wilhelm Bachaus ^ Don’ts for Artists by Cyril Scott ^ Marvels of the Human Voice by Oscar Saenger How to be a Drum Major by J. B. Cragun & Queer Notation by F. Berger. _.. ____ _ . OCTOBER 1926 Page 707 The Schirmer Catalogs COMPLETE CATALOG FOR THE STUDENT MELODYLAND r By J- Lawrence Erl, By C. W. Krogmann By ] 3fS-S“^£ri?T Pment8M3U2SiC f°r Wlnd and Str,n« Instru- Tfie DILLER and QUAILE HAZEL GERTRUDE BOOKS KINSCELLA’S WORKS GERANIUM SEWING CLUB 5K"! By Matfulde Bilbro ‘her-. -

111036-37 Bk Fledermaus

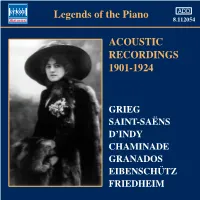

112054 bk Legends EU 4/5/10 08:33 Page 5 Princess Marcelina Czartoryska. Here, Janotha plays For Liszt and pedagogues like Theodor Leschetizky and pupil, Friedheim became Liszt’s teaching assistant, Friedheim, born in St Petersburg. Twice offered the ADD from Chopin’s own manuscript of a Bach-inspired Anton Rubinstein, the piano was a one-piece orchestra, personal secretary, and confidant. He was probably the directorship of the New York Philharmonic, honoured at Legends of the Piano youthful work (with Chopin’s handwritten notations) the synthesizer of its time, to be “conducted” for a full closest student of all to Liszt, both in piano technique the Taft White House and the courts of Europe, 8.112054 given her by the princess. Even in an age of range of colour and effect through rubato, individual (the sweeping “grand manner”) and general Friedheim was banned from the concert stage and eccentricity, Mme Janotha stood apart: as Mark accentuations, and pedal artistry. In the twentieth temperament (intensely philosophical, with spiritual reduced overnight to playing for the silent movies and Hambourg observed, her concerts were always adorned century, these two approaches survived in the mellow overtones), even sharing a physical resemblance. the vaudeville circuit. His combustible reading of by “a magnificent black cat, without which she declared singing line of Artur Rubinstein, protégé of Joseph “Friedheim’s recital,” to one newspaper critic in 1922, Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, says a 1915 review in that it was impossible for her to play a single note, and Joachim, the great violinist and intimate of Brahms and “was more of a séance”. -

Liszt' S Technical Studies: a Methodology for the Attainment of Pianistic Virtuosity

LISZT' S TECHNICAL STUDIES: A METHODOLOGY FOR THE ATTAINMENT OF PIANISTIC VIRTUOSITY BY NEIL GOODCHILD THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC (RESEARCH) THE SCHOOL OF ENGLISH, MEDIA AND PERFORMING ARTS MUSIC AND MUSIC EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES OCTOBER 2007 ABSTRACT In 1970, the Hungarian publishing firm Editio Musica Budapest began a long term project, ending in 2005, that endeavored to compile and publish all Liszt's works in a complete edition titled, The New Liszt Edition (NLE). Through the efforts of this firm, Liszt' s Technical Studies were published in the way that he had originally intended for the first time in 1983. Yet, although the eminent Liszt-scholar Michael Saffle has stated that 'Pedagogy is one of the most thoroughly-mined veins of Liszt material ever uncovered', academic discussions on Liszt's Technical Studies (Walker, 2005), his definitive pedagogical work for piano, are scarce. What it was that Liszt set out as being fundamental to the acquisition of pianistic virtuosity in the Technical Studies and the nature of its trajectory is generally unknown. Through an examination of the didactic instruction Liszt supplied in the Preface of the autograph manuscript to the Technical Studies and specific technical commentaries written by Mme. Auguste Boissier in her Liszt pedagogue, I will argue that the Technical Studies are built on six artistic and mechanical principles, exemplified by Liszt in the exercises, written to help the pianist acquire technical virtuosity. The methodical divisions of the work into sections that deal with specific mechanical objectives are illustrated with musical examples and their technical trajectory defined. -

Franz Liszt and the Seven Rays

Spring 2014 Franz Liszt and the Seven Rays Celeste Jamerson Franz Liszt, Portrait by Ary Scheffer1 Abstract the soul, personality, mind, emotions and phys- ical body. Although a detailed analysis of he purpose of this article is to study the Liszt’s astrological chart is beyond the scope T influence of the seven rays in the life of of the present article, some consideration also the great Romantic composer Franz Liszt. The will be given to the rays as they influence Liszt first part of this article will give a short synop- through planets and points in his chart. Specu- sis of Liszt’s life and work and the important lation will also be given as to a possible past- role he played in the history of classical mu- life ray influence. sic.2 A brief explanation of the seven rays will _____________________________________ follow. Each ray then will be described in terms of its influence on the life and work of About the Author Liszt. Liszt’s life, his music, his relationships, Celeste Jamerson is a soprano and teacher of sing- and his prose writings will be examined for ing in the New York metropolitan area. She has a signs of the influence of the rays. An effort BM in voice performance from Oberlin Conserva- will be made to determine which rays condi- tory, a BA in German Studies from Oberlin Col- tion Liszt on various levels. These are the same lege, an MM in voice performance (with distinc- levels which were used by the Tibetan Master tion) from Indiana University, and a DMA in voice performance from the University of North Carolina Djwhal Khul, hereafter referred to simply as at Greensboro. -

Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’S Marche Hongroise D’Après Schubert

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Loya, S. (2016). Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’s Marche hongroise d’après Schubert. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 69(2), pp. 409-476. doi: 10.1525/jams.2016.69.2.409 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15059/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/jams.2016.69.2.409 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Recomposing National Identity: Four Transcultural Readings of Liszt’s Marche hongroise d’après Schubert SHAY LOYA A Curious Attachment Sometime in 1882, past his seventieth year, Liszt decided that an old piece of his deserved another revision. This resulted in the last of many arrange- ments of the Marche hongroise d’après Schubert, a work that originally took form as the second movement of the Mélodies hongroises d’après Schubert of 1838–39 (S.