The Music of Wagner in Toronto Before 1914 Carl Morey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

By Richard Wagner 1856 Ride of the Valkyries

KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER: KEY PIECES OF MUSIC 6 BY RICHARD RIDE WAGNER OF THE 1856 VALKYRIES THE STORY—well, a short snippet of it... Wotan has 9 daughters. These are the Valkyries whose task it is to recover heroes fallen in battle and bring them back to Valhalla where they will protect Wotan’s fortress. Wotan hopes for a hero who will take a ring from the dragon. Wotan has two other children who live on Earth; twins called Siegmund and Sieglinde. They grow up separately but meet one day. Siegmund plans to battle Sieglinde’s husband as she claims he forced her to marry him. Wotan believes Siegmund wants to capture and keep the ring and won’t protect him. He sends one of his Valkyrie daughters to bring him to Valhalla but he refuses to go without his sister. She tries to help him in battle against her father’s wishes but sadly he dies. Meanwhile, the Valkyries congregate on the mountain-top, each carrying a dead hero and chattering excitedly when the daughter arrives with Sieglinde. Wotan is furious and plans to punish her. Prelude An introductory piece of music. A prelude often opens an act in an opera Act A musical, play or opera is often split into acts. There is often an interval between acts THE MUSIC THE COMPOSER Ride of the Valkyries is only part of a Wagner loved the brass section and even huge major work. It is taken from a cycle invented the Wagner Tuba which looks like of 4 massive operas known as The Ring a cross between a French horn and of the Nibelungs or The Ring for short. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

Andréas Hallén's Letters to Hans

”Klappern und wieder klappern! Die Leute glauben nur was gedruckt steht.” ”Klappern und wieder klappern! Die Leute glauben nur was gedruckt steht.”1 Andréas Hallén’s Letters to Hans Herrig. A Contribution to the Swedish-German Cultural Contacts in the Late Nineteenth Century Martin Knust It is beyond question that the composer Andréas Hallén (1846–1925) never stood in the front line of Swedish musical life. Nevertheless, the ways he composed and promoted his music have to be regarded as very advanced for his time. As this study reveals, Hallén’s work as a composer and music critic may have served as a model for the next generation of composers in Sweden. Moreover, his skills as an orchestra- tor as well as his cleverness in building up networks on the Continent can hardly be overestimated. Hallén turns out to have been quite a modern composer in that he took over the latest music technologies and adapted them to a certain music market. The study of Hallén and his work exposes certain musical and cultural developments that were characteristic for Sweden at the turn of the century. Documents that just recently became accessible to research indicate that it is time to re-evaluate Hallén’s role in Swedish musical life. Correspondence between opera composers and their librettists provides us with a wealth of details about the genesis of these interdisciplinary art works and sometimes even, like the correspondence Strauss–Hofmannsthal, about the essence of opera itself. In the case of the Swedish composer Andréas2 Hallén, his first opera Harald der Wiking was not only an interdisciplinary but also an international project because he worked together with the German dramatist Hans Herrig (1845–1892). -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

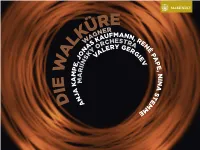

WAGNER / Рихард Вагнер DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (Conclusion) 1 Xii

lk a Waü GN r W , joNas k e e pe kY au r m iNs or f e ri C m i a a Val H k er e a m Y s N a t D j N G r N e , a r a r e G N i e é V p a p e , N i N a s t e e m m 2 Die Walküre Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР DISC 3 45’41” (1813–1883) Zweiter Aufzug – Act Two (conclusion) 1 xii. Schwer wiegt mir der Waffen Wucht / My load of armour weighs heavy on me p18 2’28” DiE WAlkÜRE 2 xiii. Dritte Szene: Raste nun hier, gönne dir Ruh’! / Scene Three: Do stop here, and take a rest p18 8’56” (ThE VAlkyRiE / ВалькиРия) 3 xiv. Wo bist du, Siegmund? / Where are you, Siegmund? p19 3’49” 4 xv. Vierte Szene: Siegmund! Sieh auf mich! / Scene Four: Siegmund, look at me p19 10’55” Siegmund / Зигмунд...................................................................................................................................Jonas KAUFMANN / Йонас Кауфман 5 xvi. Du sahst der Walküre sehrenden Blick / you have seen the Valkyrie’s searing glance p20 4’27” hunding / Хундинг................................. ..............................................................................................Mikhail PETRENKO / михаил ПетренКо 6 xvii. So jung un schön erschimmerst du mir / So young and fair and dazzling you look p20 4’58” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René Pape / рене ПаПе 7 xviii. Funfte Szene: Zauberfest bezähmt ein Schlaf / Scene Five: Deep as a spell sleep subdues p21 3’01” Sieglinde / Зиглинда........................................................................................................................................................Anja -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera. -

Wagner Operas

lONDOn PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA Orchestral excerpts frOm Wagner Operas from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1868) The London Philharmonic Orchestra has long Vladimir Jurowski was appointed the 01 10:51 Prelude established a high reputation for its versatility Orchestra’s Principal Guest Conductor in and artistic excellence. These are evident from March 2003. The London Philharmonic from Rienzi (1842) its performances in the concert hall and opera Orchestra has been resident symphony 02 13:07 Overture Orchestral excerpts frOm house, its many award-winning recordings, orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall since 1992 its trail-blazing international tours and its and there it presents its main series of concerts from Der Ring des Nibelungen Wagner Operas pioneering education work. Kurt Masur has between September and May each year. Götterdämmerung (1876) been the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor In summer, the Orchestra moves to Sussex 03 11:59 Dawn and Siegfried’s Journey to the Rhine Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, since September 2000, extending the line where it has been the resident symphony 04 10:09 Siegfried’s Funeral Music Rienzi, Götterdämmerung, of distinguished conductors who have held orchestra at Glyndebourne Festival Opera for positions with the Orchestra since its over 40 years. The Orchestra also performs Die Walküre (1870) Die Walküre, Tannhäuser foundation in 1932 by Sir Thomas Beecham. at venues around the UK and has made 05 5:08 The Ride of the Valkyries (concert version) These have included Sir Adrian Boult, Sir John numerous tours to America, Europe and Japan, Pritchard, Bernard Haitink, Sir Georg Solti, and visited India, Hong Kong, China, South 25:38 from Tannhäuser (1845) Klaus tennstedt conductor Klaus Tennstedt and Franz Welser-Möst. -

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON at PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018

THE 2018–19 CONCERT SEASON AT PEABODY Peabody Studio Orchestra Saturday, November 17, 2018 Peabody Conductors' Orchestra Tuesday, November 27, 2018 Peabody Symphony Orchestra Saturday, December 1, 2018 STEINWAY. YAMAHA. [ YOUR NAME HERE ] With your gi to the Piano Excellence Fund at Peabody, you can add your name to the quality instruments our outstanding faculty and students use for practice and performance every day. The Piano Department at Peabody has a long tradition of excellence dating back to the days of Arthur Friedheim, a student of Franz Liszt, and continuing to this day, with a faculty of world-renowned artists including the eminent Leon Fleisher, who can trace his pedagogical lineage back to Beethoven. Peabody piano students have won major prizes in such international competitions as the Busoni, Van Cliburn, Naumburg, Queen Elisabeth, and Tchaikovsky, and enjoy global careers as performers and teachers. The Piano Excellence Fund was created to support this legacy of excellence by funding the needed replacement of more than 65 pianos and the ongoing maintenance and upkeep of nearly 200 pianos on stages and in classrooms and practice rooms across campus. To learn more about naming a piano and other creative ways to support the Peabody Institute, contact: Jessica Preiss Lunken, Associate Dean for External Affairs [email protected] • 667-208-6550 Welcome back to Peabody and the Miriam A. Friedberg Concert Hall. This month’s programs show o a remarkable array of musical styles and genres especially as related to Peabody’s newly imagined ensembles curriculum, which has evolved as part of creating the Conservatory’s groundbreaking Breakthrough Curriculum. -

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) S Elise Braun Barnett

An Annotated Translation of Moriz Rosenthal) s Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections Elise Braun Barnett Introduction Otto Deri often used to discuss programs for piano recitals with me. More than once he expressed surprise that the late piano compositions of Liszt were performed only rarely. He recommended their serious study since, as he pointed out, in these pieces Liszt's conception of melody, rhythm, and harmony are quite novel and anticipate Debussy, Ravel, and Bartok. These discussions came to mind when a friend of mine, Mrs. Oscar Kanner, a relative of Moriz Rosenthal,! showed me an article by the pianist entitled "Franz Liszt, Memories and Reflections," which had appeared in a 1911 issue of the journal Die Musik,2 and also a handwritten, unpublished autobiography written in New York during the last years of Rosenthal's life, 1940 to 1946. Rosenthal's concerts in Europe and America are still remembered by the older generation. His musical conceptions, emotions projected on the piano with an amazing technique, remain an unforgettable experience. He is also remembered as having been highly cultivated, witty, and sometimes sar- castic. His skill in writing is less known, but his autobiography and essays reveal a most refined, fluent, and vivid German style. He is able to conjure up the "golden days," when unity of form and content was appreciated. It is my hope that the following annotated translation of Rosenthal's article will provide a worthy tribute to the memory of Otto Deri. Translation In October of 1876, as a youngster of thirteen, I played for Franz Liszt during one of his frequent visits to the Schottenhof in Vienna,3 and I was admitted to his much envied entourage as perhaps the youngest of his disciples.