200 Marie Zimmerman When Discussing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Protección De La Intimidad Y Vida Privada En Internet La Integridad

XIX Edición del Premio Protección de Datos Personales de Investigación de la Agencia Española de Protección de Datos PREMIO 2015 Las redes sociales se han convertido en una herramienta de comu- nicación y contacto habitual para millones de personas en todo el La protección de la intimidad mundo. De hecho, se calcula que más de un 75% de las personas Amaya Noain Sánchez que se conectan habitualmente a Internet cuentan con al menos un y vida privada en internet: la perfil en una red social. La autora plantea en el texto si las empre- sas propietarias de estos servicios ofrecen una información sufi- integridad contextual y los flujos de ciente a los usuarios sobre qué datos recogen, para qué los van a información en las redes sociales utilizar y si van a ser cedidos a terceros. En una reflexión posterior, propone como posibles soluciones el hecho de que estas empresas (2004-2014) pudieran implantar directrices técnicas compartidas y una adapta- ción normativa, fundamentalmente con la privacidad desde el di- seño, la privacidad por defecto y el consentimiento informado. Así, Amaya Noain Sánchez el resultado sería un sistema de información por capas, en el que el usuario fuera conociendo gradualmente las condiciones del trata- miento de su información personal. Este libro explica el funcionamiento de una red social, comenzan- do por la creación del perfil de usuario en el que se suministran datos, y analiza cómo la estructura del negocio está basada en la monetización de los datos personales, con sistemas como el targe- ting (catalogando al usuario según sus intereses, características y predilecciones) y el tracking down (cruzando información dentro y fuera de la red). -

October 14 2010 the Facebook Story and the Future of the Social Web, Chris Hughes

October 14 2010 The Facebook story and the future of the social web, Chris Hughes The social networking site Facebook may have been one of the biggest developments in business and society in recent years, but it was just a natural outgrowth of existing Internet trends, Facebook cofounder Chris Hughes said at the World Knowledge Forum Thursday. “It was a natural extension of what was required to enable everyday people to connect and share with their friends,” Hughes said. Hughes spoke to large audience on various aspects of social media, including the genesis of Facebook, the core values that allowed it to develop, his role in Barack Obama’s online campaign, his current ‘Jumo’ project and the future of social media in general. He said the creation of Facebook was not about magic or secrets. “The birth of any cultural phenomenon almost always comes with myth- making,” Hughes said, beginning his presentation by debunking some of preconceptions about the founding of Facebook. He debunked the image of Facebook as having been founded by a lone genius who turned an idea into a multi-billion-dollar operation. “I have news - it’s not true,” he said, explaining that Facebook was founded by himself, Mark Zuckerberg and Dustin Muskovitz in a spirit of scepticism of the control that Harvard and other institutions had over the control of information. He explained that authorities at Harvard, where he was a student, shut down two earlier attempts by Hughes and his partners to start social networking sites. So the partners decided to make Facebook more independent. -

La Protección De La Intimidad Y Vida Privada En Internet La Integridad

XIX Edición del Premio Protección de Datos Personales de Investigación de la Agencia Española de Protección de Datos PREMIO 2015 Las redes sociales se han convertido en una herramienta de comu- nicación y contacto habitual para millones de personas en todo el La protección de la intimidad mundo. De hecho, se calcula que más de un 75% de las personas Amaya Noain Sánchez que se conectan habitualmente a Internet cuentan con al menos un y vida privada en internet: la perfil en una red social. La autora plantea en el texto si las empre- sas propietarias de estos servicios ofrecen una información sufi- integridad contextual y los flujos de ciente a los usuarios sobre qué datos recogen, para qué los van a información en las redes sociales utilizar y si van a ser cedidos a terceros. En una reflexión posterior, propone como posibles soluciones el hecho de que estas empresas (2004-2014) pudieran implantar directrices técnicas compartidas y una adapta- ción normativa, fundamentalmente con la privacidad desde el di- seño, la privacidad por defecto y el consentimiento informado. Así, Amaya Noain Sánchez el resultado sería un sistema de información por capas, en el que el usuario fuera conociendo gradualmente las condiciones del trata- miento de su información personal. Este libro explica el funcionamiento de una red social, comenzan- do por la creación del perfil de usuario en el que se suministran datos, y analiza cómo la estructura del negocio está basada en la monetización de los datos personales, con sistemas como el targe- ting (catalogando al usuario según sus intereses, características y predilecciones) y el tracking down (cruzando información dentro y fuera de la red). -

Privacy-Oriented Regulation of Social Media Platforms

Privacy-Oriented Regulation of Social Media Platforms by Harry Han An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2019 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Michael Posner Faculty Adviser Thesis Adviser Acknowledgements While many people have contributed to this paper, I would like to especially thank three people: • I would like to thank Professor Michael Posner for his insights, editing guidance, and passion for the subject area of human rights—especially for pushing myself and the rest of my BPE classmates during Senior Capstone to think beyond the numbers. • I would like to thank Professor Marti Subrahmanyam and everyone at the NYU Stern Office of Student Engagement for organizing the program. • Lastly, I would like to thank my friend Jennifer, who was always there for me— especially during the (rare, but) turbulent times of creating this thesis. Disclosure • This paper specifically discusses regulations as they pertain to the US. • This thesis was researched and written concurrently for another course, also in partial fulfillment of my degree. As such, some portions of this paper may overlap with the mentioned paper, titled “BPE Senior Paper: Facebook’s Broken Data Privacy,” submitted 23 December 2018. Professor Michael Posner was my advisor for both papers; and Professor Marti Subrahmanyam, the faculty advisor, was aware of this concurrent research arrangement. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements -

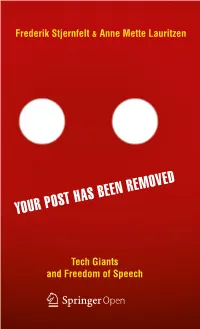

Your Post Has Been Removed

Frederik Stjernfelt & Anne Mette Lauritzen YOUR POST HAS BEEN REMOVED Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Your Post has been Removed Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Your Post has been Removed Tech Giants and Freedom of Speech Frederik Stjernfelt Anne Mette Lauritzen Humanomics Center, Center for Information and Communication/AAU Bubble Studies Aalborg University University of Copenhagen Copenhagen København S, København SV, København, Denmark København, Denmark ISBN 978-3-030-25967-9 ISBN 978-3-030-25968-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25968-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permit- ted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

The Social Network

FROM THE BLACK WE HEAR-- MARK (V.O.) Did you know there are more people with genius IQ’s living in China than there are people of any kind living in the United States? ERICA (V.O.) That can’t possibly be true. MARK (V.O.) It is. ERICA (V.O.) What would account for that? MARK (V.O.) Well, first, an awful lot of people live in China. But here’s my question: FADE IN: INT. CAMPUS BAR - NIGHT MARK ZUCKERBERG is a sweet looking 19 year old whose lack of any physically intimidating attributes masks a very complicated and dangerous anger. He has trouble making eye contact and sometimes it’s hard to tell if he’s talking to you or to himself. ERICA, also 19, is Mark’s date. She has a girl-next-door face that makes her easy to fall for. At this point in the conversation she already knows that she’d rather not be there and her politeness is about to be tested. The scene is stark and simple. MARK How do you distinguish yourself in a population of people who all got 1600 on their SAT’s? ERICA I didn’t know they take SAT’s in China. MARK They don’t. I wasn’t talking about China anymore, I was talking about me. ERICA You got 1600? MARK Yes. I could sing in an a Capella group, but I can’t sing. 2. ERICA Does that mean you actually got nothing wrong? MARK I can row crew or invent a 25 dollar PC. -

Founder Mark Zuckerberg, Eduardo Saverin, Dustin Moskovitz, Chris Hughes

Facebook Facebook, Inc. Type Private Founded Cambridge, Massachusetts[1] (2004) Founder Mark Zuckerberg, Eduardo Saverin, Dustin Moskovitz, Chris Hughes Headquarters Palo Alto, California, U.S., will be moved to Menlo Park, California, U.S. in June 2011 Area served Worldwide Mark Zuckerberg (CEO), Chris Cox (VP of Product), Sheryl Sandberg (COO), Donald E. Key people Graham (Chairman) Net income N/A Website facebook.com Type of site Social network service Registration Required Users 600 million[5][6] (active in January 2011) Launched February 4, 2004 Current status Active Facebook (stylized facebook) is a social network service and website launched in February 2004, operated and privately owned by Facebook, Inc. As of January 2011, Facebook has more than 600 million active users. Users may create a personal profile, add other users as friends, and exchange messages, including automatic notifications when they update their profile. Additionally, users may join common interest user groups, organized by workplace, school, or college, or other characteristics. The name of the service stems from the colloquial name for the book given to students at the start of the academic year by university administrations in the USA to help students get to know each other better. Facebook allows anyone who declares themselves to be at least 13 years old to become a registered user of the website. Facebook was founded by Mark Zuckerberg with his college roommates and fellow computer science students Eduardo Saverin, Dustin Moskovitz and Chris Hughes. The website's membership was initially limited by the founders to Harvard students, but was expanded to other colleges in the Boston area, the Ivy League, and Stanford University. -

US Magazine New Republic Sold After Upheaval 27 February 2016

US magazine New Republic sold after upheaval 27 February 2016 posting. "I look forward to watching their progress over the years to come." Hughes, 32, invested more than $20 million in an effort to bring The New Republic into the digital era. But in January, he acknowledged it was not working, saying, "I underestimated the difficulty of transitioning an old and traditional institution into a digital media company in today's quickly evolving climate." Hughes, a Harvard roommate of Facebook co- Facebook's co-founder Chris Hughes, who invested founder Mark Zuckerberg and part of the original more than $20 million in an effort to bring The New team at the social network, had faced friction with Republic into the digital era, announced the magazine's the editorial staff. sale Friday It turned into a full-scale revolt in 2014 when Hughes decided to shake up the top management and reconfigure the publication as a digital media US magazine The New Republic is being sold after organization. a failed four-year effort to revitalize the century-old publication by a Facebook entrepreneur, the owner In a statement, McCormack said he hoped to said Friday. maintain the magazine's traditions. Chris Hughes, the Facebook co-founder who in "The New Republic was founded in 1914 as the 2012 bought the publication that has been a organ of a modernized liberalism and then- leading left-wing voice, announced the sale to Win dominant Progressive Movement, and has McCormack, editor of the literary quarterly Tin remained true to its founding principles, under all its House and a political activist. -

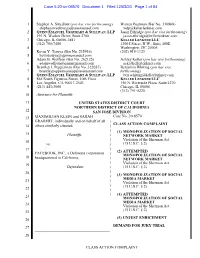

Class Action Complaint 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Case 5:20-cv-08570 Document 1 Filed 12/03/20 Page 1 of 84 1 Stephen A. Swedlow (pro hac vice forthcoming) Warren Postman (Bar No. 330869) [email protected] [email protected] 2 QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP Jason Ethridge (pro hac vice forthcoming) 191 N. Wacker Drive, Suite 2700 [email protected] 3 Chicago, IL 60606-1881 KELLER LENKNER LLC (312) 705-7400 1300 I Street, N.W., Suite 400E 4 Washington, DC 20005 Kevin Y. Teruya (Bar No. 235916) (202) 918-1123 5 [email protected] Adam B. Wolfson (Bar No. 262125) Ashley Keller (pro hac vice forthcoming) 6 [email protected] [email protected] Brantley I. Pepperman (Bar No. 322057) Benjamin Whiting (pro hac vice 7 [email protected] forthcoming) QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP [email protected] 8 865 South Figueroa Street, 10th Floor KELLER LENKNER LLC Los Angeles, CA 90017-2543 150 N. Riverside Plaza, Suite 4270 9 (213) 443-3000 Chicago, IL 60606 (312) 741-5220 10 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 12 SAN JOSE DIVISION Case No. 20-8570 13 MAXIMILIAN KLEIN and SARAH GRABERT, individually and on behalf of all ) others similarly situated, ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT 14 ) (1) MONOPOLIZATION OF SOCIAL 15 Plaintiffs, ) NETWORK MARKET ) Violation of the Sherman Act 16 vs. ) (15 U.S.C. § 2) 17 ) FACEBOOK, INC., a Delaware corporation ) (2) ATTEMPTED MONOPOLIZATION OF SOCIAL 18 headquartered in California, ) NETWORK MARKET ) Violation of the Sherman Act 19 Defendant. ) (15 U.S.C. § 2) 20 ) ) (3) MONOPOLIZATION OF SOCIAL ) MEDIA MARKET 21 Violation of the Sherman Act ) (15 U.S.C. -

November 12, 2020 the Honorable Joseph J. Simons Federal Trade

November 12, 2020 The Honorable Joseph J. Simons Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 Dear Chairman Simons: Competition is the backbone of American industry and the engine that drives our entrepreneurial spirit. Monopolies, however, cause stagnation and smother innovation. As the Commission presses forward with its ongoing antitrust investigation of Facebook, I urge that you consider interviewing former employees to target the full scope of the company’s anticompetitive conduct. I understand that Mr. Zuckerberg sat for a deposition with the Commission this summer. While that is promising, I encourage you to also speak to other Facebook executives and engineers who can reveal the company’s real agenda. Many of them fear letting Facebook’s dominance go unchecked can hold dark consequences for competitors and consumers alike. • Company co-founder Chris Hughes believes it is time to break up Facebook, which he calls a “powerful monopoly, eclipsing all of its rivals and erasing competition.” On Mr. Zuckerberg’s influence, he said, “Mark alone can decide how to configure Facebook’s algorithms to determine what people see in their News Feeds, what privacy settings they can use and even which messages get delivered.”1 • Former Chief Security Officer Alex Stamos said Mr. Zuckerberg should step down because he holds “too much power.”2 He compared Facebook to “a banana republic.”3 • Yaël Eisenstat, the former Head of Global Elections Integrity Operations, said, “Facebook profits partly by amplifying lies and -

The Social Network

The Social Network 12 - Curs 2011 Curs Cinema per a Estudiants per a Cinema The Social Network Pel·lícula recomanada per a: 3er i 4art d’ESO. Batxillerats. Cicles Formatius. Centres de Formació d’Adults Àrees del currículum: Llengua anglesa; Ciències socials; Informàtica, internet; Món contemporani. Temes: Biografia; Relacions humanes, psicologia; El món del treball, relacions laborals; Adaptació cinematogràfica d’obra literària. www.cinemaperaestudiants.cat The Social Network Direcció: David Fincher. Interpretació: Jesse Eisenberg (Mark Zuckerberg), Andrew Garfield (Eduardo Saverin), Justin Timberlake (Sean Parker), Armie Hammer (Cameron Winklevoss / Tyler Winklevoss), Max Minghella (Divya Narendra), Rooney Mara (Erica), Rashida Jones (Marylin Delpy). Guió: Aaron Sorkin; basat en el llibre “Multimilionaris per accident” de Ben Mezrich. Producció: Dana Brunetti, Ceán Chaffin, Michael De Luca i Scott Rudin. Música: Trent Reznor i Atticus Ross. Fotografia: Jeff Cronenweth. Muntatge: Kirk Baxter i Angus Wall. Disseny de producció: Donald Graham Burt. Vestuari: Jacqueline West. Gènere: Drama. País: USA. Any: 2010. Durada: 122 min. Sinopsi En aquest film, el director David Fincher i el guionista Aaron Sorkin exploren el moment de la invenció de Facebook, un dels fenòmens socials més revolucionaris del nou segle. La pel·lícula, basada en múltiples fonts, ens trasllada des dels passadissos de Harvard fins a la seu de la companyia a Palo Alto, on captura l'emoció dels inicis d’aquest fenomen que primerament va unir i després va separar un grup de joves pioners de les xarxes socials. El protagonista del film és Mark Zuckerberg, el brillant alumne de Harvard creador d’una pàgina web que sembla haver redefinit el nostre teixit social de la nit al dia. -

Conceptual Design of a Database for a Social Network Let's Turn Back Time

Conceptual Design of a database for a social network Let’s turn back time approximately 8 years. Mark Zuckerberg and his fellow students Eduardo Saverin, Dustin Moskovitz und Chris Hughes were sitting together, planning Facebook. They brainstorm the following requirements: • For every user a profile is created. There, the following data should be stored – name of the user (first, last and username) – favorite Bands (a list of Bands that the user likes) – political views – looking for (e.g. friendship, relationship, same sex relationship, open relationship,…) • A user (profile) can be friends with other users. The other user needs to agree or decline. • A user (profile) can have a pin board. There, the user can make pin board entries- either for his/herself or for other users. These entries have a text and/or a date of creation. These entries can have a photo and they can be commented. The comments have a position (order) on the pin board, depending on the time, that it was created. • When a photo is uploaded, the url through what it can be reached is stored, a description of the picture and the date and time. Users can upload a photo for their profile. • A user (profile) can create groups. These have a description and pin board entries. Groups are public (open) or not (closed). If they are not, users need to register for a membership, the creator of the group then agrees on or denies the membership. Hence, a “status” of membership (member, not replied, declined) needs to be stored. • A user (profile) can create events.