Download Published Versionadobe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Add Your Voice If You Want a Choice

Who Are We Mr Nick GOIRAN PERTH UPPER Unit 2, 714 Ranford Road, Go Gentle Go Gentle Australia, founded by Andrew Denton, is an SOUTHERN RIVER WA 6110 Australia expert advisory and health promotion charity for a better HOUSE MEMBERS Ph: (08) 9398 3800 Mr Simon O’BRIEN conversation around death, dying and end of life choices. North Metropolitan 904 Canning Highway, Our campaigning efforts in Victoria in 2017 provided Mr Peter COLLIER CANNING BRIDGE WA 6153, or Shop 23A, Warwick Grove Corner Beach PO Box 919, CANNING BRIDGE WA 6153 IF YOU WANT critical assistance to those in the Victorian parliament Road and Erindale Road, WARWICK WA E: [email protected] who fought for and ultimately succeeded in the historic 6024, or PO Box 2606, WARWICK WA 6024 Ph: (08) 9364 4277 E: [email protected] passing of Voluntary Assisted Dying legislation. Mr Aaron STONEHOUSE A CHOICE, Ph: (08) 9203 9588 Level 1, Sterling House, In Western Australia, we are supporting a campaign to Ms Alannah MacTIERNAN 8 Parliament Place, Unit 1, 386 Wanneroo Road, WEST PERTH WA 6005 see parliament pass a Voluntary Assisted Dying law WESTMINSTER WA 6061 E: [email protected] ADD YOUR VOICE similar to Victoria’s. E: [email protected] Ph: (08) 9226 3550 Ph: (08) 6552 6200 Mr Pierre YANG Please help us to be heard Mr Michael MISCHIN Unit 1, 273 South Street, HILTON WA TELL YOUR MPs YOU WANT THEM TO SUPPORT Unit 2, 5 Davidson Terrace, 6163 or PO Box 8166, Hilton WA 6163 THE VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING BILL. -

P5425b-5431A Hon Kate Doust; Hon Robin Chapple; Hon Peter Collier

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Tuesday, 18 August 2015] p5425b-5431a Hon Kate Doust; Hon Robin Chapple; Hon Peter Collier ELECTION OF SENATORS AMENDMENT BILL 2015 Second Reading Resumed from 26 March. HON KATE DOUST (South Metropolitan — Deputy Leader of the Opposition) [5.48 pm]: On behalf of the opposition, I am pleased to say a few words in support of the Election of Senators Amendment Bill 2015. The bill was read into the house in March this year. It is a relatively simple bill with only four clauses, one of which provides the change. I know that the minister responsible is probably very keen to expeditiously get this bill through today. Given that we are not too sure about the federal government’s election timetable, it may be that we need to ensure that the bill is passed a lot faster than originally planned. However, I do not want to disturb the minister and have him think that I have not paid appropriate attention to this legislation or have him accuse me at a later stage of not spending enough time on the bill, so I will go through a few things and provide a little background for members as to why this piece of legislation is in front of us. As I said, it is a fairly straightforward bill with only four clauses and deals with the election of senators. The original bill was introduced into this Parliament in 1903 and assented to on 11 December in the same year. I am sure Hon Jim Chown will recall it; he was probably around at that time! I will go into some of the history. -

![[COUNCIL — Wednesday, 12 May 2021] P448b-455A Hon Robin Scott; Hon Robin Chapple Became a Key Player in My Team](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0243/council-wednesday-12-may-2021-p448b-455a-hon-robin-scott-hon-robin-chapple-became-a-key-player-in-my-team-3280243.webp)

[COUNCIL — Wednesday, 12 May 2021] P448b-455A Hon Robin Scott; Hon Robin Chapple Became a Key Player in My Team

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 12 May 2021] p448b-455a Hon Robin Scott; Hon Robin Chapple became a key player in my team. Both these ladies went above and beyond their duties and never complained when I asked them to work late or to pop into the office when I needed help at the weekend. Thanks, girls. I will not forget the support you gave me and all the times you picked me up and dropped me off at the airport. Mr David Modolo, my electorate officer, travelled everywhere in the electorate with me—from Norseman to Kalumburu and everywhere in between. On some of our flights, we spent three or four hours in the air, with the worst inflight service you could imagine. We could only eat and drink what we brought along, but not once did he complain. Being newly married, he never kicked up when I asked him to bring a suitcase because we were going to the bush for a while. During the flights, we spent much of our time discussing the reasons for the trip. When we landed, I was always full bottle on the issues and where we stood on the issues. David was a great electorate officer for me. He had had a similar role in federal politics, and I was the one who gained from all his experience. He will always be a good friend. My family know that I was never put on this earth to be a good father or a papa or a brother or even a husband. My role was as a worker and provider. -

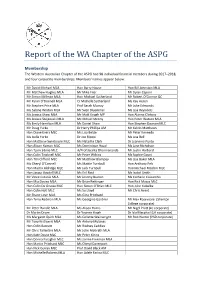

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Western Australian Chapter of the ASPG had 98 individual financial members during 2017–2018, and four corporate memberships. Members’ names appear below: Mr David Michael MLA Hon Barry House Hon Bill Johnston MLA Mr Matthew Hughes MLA Mr Mike Filer Mr Dylan Caporn Mr Simon Millman MLA Hon Michael Sutherland Mr Robert O’Connor QC Mr Kyran O’Donnell MLA Cr Michelle Sutherland Ms Kay Heron Mr Stephen Price MLA Prof Sarah Murray Mr Luke Edmonds Ms Sabine Winton MLA Mr Sven Bluemmel Ms Lisa Reynders Ms Jessica Shaw MLA Mr Matt Keogh MP Hon Alanna Clohesy Ms Jessica Stojkovski MLA Mc Mihael McCoy Hon Peter Watson MLA Ms Emily Hamilton MLA Mr Daniel Shaw Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Mr Doug Yorke Dr Harry Phillips AM Mr Kelvin Matthews Hon Diane Evers MLC Ms Lisa Belde Mr Peter Kennedy Ms Izella Yorke Dr Joe Ripepi Ms Lisa Bell Hon Matthew Swinbourn MLC Ms Natasha Clark Dr Jeannine Purdy Hon Alison Xamon MLC Ms Dominique Hoad Ms Jane Nicholson Hon Tjorn Sibma MLC A/Prof Jacinta Dharmananda Mr Justin Harbord Hon Colin Tincknell MLC Mr Peter Wilkins Ms Sophie Gaunt Hon Tim Clifford MLC Mr Matthew Blampey Ms Lisa Baker MLA Ms Cheryl O’Connell Ms Mattie Turnbull Hon Anthony Fels Hon Martin Aldridge MLC Mr Jack Turnbull Hon Michael Mischin MLC Hon Jacqui Boydell MLC Ms Eril Reid Ms Isabel Smith Mr Vince Catania MLA Mr Jeremy Buxton Ms Catharin Cassarchis Hon Mia Davies MLA Mr Brian Rettinger Hon Rick Mazza MLC Hon Colin De Grussa MLC Hon Simon O’Brien MLC Hon John Kobelke Hon Colin Holt MLC Ms Su Lloyd -

South Metropolitan Region

2021 WA Election – Legislative Council Tickets SOUTH METROPOLITAN REGION 35 H 1 Steven Tonge SFF Group A - Independent - WEST 36 H 2 Paul Bedford SFF 37 E 1 Samantha Vinci Great Australian Party Grp/Order Candidate Party 38 E 2 Susan Hoddinott Great Australian Party 39 S 1 Cam Tinley No Mandatory Vacc. 1 A 1 Graham West Independent 40 S 2 Michael Joseph Fletcher No Mandatory Vacc. 2 A 2 Liam Strickland Independent 41 S 3 Greg Bell No Mandatory Vacc. 3 M 1 Aaron Stonehouse Liberal Democrats 42 O 1 Moshe Bernstein Legalise Cannabis WA 4 M 2 Harvey Smith Liberal Democrats 43 O 2 Scott Shortland Legalise Cannabis WA 5 M 3 Jared Neaves Liberal Democrats 44 T 1 Philip Scott One Nation 6 M 4 Ivan Tomshin Liberal Democrats 45 T 2 Bradley Dickinson One Nation 7 M 5 Laurentiu Zamfirescu Liberal Democrats 46 F 1 Brad Pettitt The Greens 8 M 6 Peter Leech Liberal Democrats 47 F 2 Lynn MacLaren The Greens 9 Q 1 Dave Glossop Independent 48 F 3 Daniel Garlett The Greens 10 Q 2 Lewis Christian Butto Independent 49 G 1 Nick Goiran Liberal Party 11 Y 1 Leon Hamilton Independent 50 G 2 Michelle Hofmann Liberal Party 12 Z 1 Larry Foley Independent 51 G 3 Ka-ren Chew Liberal Party 13 C 1 Jourdan Kestel Independent 52 G 4 Robert Reid Liberal Party 14 C 2 Lee Herridge Independent 53 G 5 Nitin Vashisht Liberal Party 15 V 1 Glen Michael Leslie Independent 54 G 6 Scott Stirling Liberal Party 16 V 2 Stephen Yarwood Independent 55 L 1 Sue Ellery WA Labor 17 J 1 Mark Rowley Independent 56 L 2 Kate Doust WA Labor 18 J 2 Marlie Touchell Independent 57 L 3 Klara Andric -

Presidents of the Legislative Council May 2016

PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA History Notes: Presidents of the Legislative Council May 2016. Updated June 2021. Presidents of the LC Chainman to president Sir Thomas Cockburn‐Campbell was born in 1845 in Exeter, England. He was the second son of Sir Alexander Cockburn‐Campbell and his second wife, Grace Spence. When he was 19 years old, Cockburn‐Campbell migrated to Australia and worked as a chainman (surveyor’s assistant) in Queensland. He moved to WA and farmed near Mt Barker. In 1870, he married Lucy Anne Trimmer of Pootenup. Governor Frederick Weld nominated him to the part elecve Legislave Council in 1872. He then won the seat of Plantagenet (Albany) in 1874. Cockburn‐Campbell wrote for the Western Australian Times and in 1879 he gave up farming to become manager and part owner of the newspaper which was renamed The West Australian. In 1890, Governor Robinson appointed him to the new nominated Legislave Council and he was elected as the first President. Tragically on 27 September 1892, Cockburn‐Campbell died in the Legislave Council building from a chlorodyne overdose, taken to induce sleep. “Doubtless the mining resources of the colony were among its richest treasures and their development must be a maer of the utmost importance” Sir Thomas Cockburn‐ Campbell Inaugural speech, Parliament of Western Australia Tuesday 1 July 1873 William Hancock and others Thomas Cockburn‐Campbell is seated in the middle, c1895 Photograph courtesy of State Library of WA (BA1886/425) The Hon Kate Doust MLC: First Woman President Catherine Esther Doust was born Western Australia graduang year. -

Western Australian State Election 2013

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN STATE ELECTION 2013 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS by Antony Green for the Western Australian Parliamentary Library and Information Services Election Papers Series No. 1/2013 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, Western Australian Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the Western Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Australian Parliamentary Library. Western Australian Parliamentary Library Parliament House Harvest Terrace Perth WA 6000 ISBN 978-0-9875969-0-1 May 2013 Related Publications 2011 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2011. Western Australian State Election 2008 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2009. 2007 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2007 Western Australian State Election 2005 - Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2005. 2003 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2003. Western Australian State Elections 2001 by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2001. Western Australian State Elections -

Hon Kate Doust MLC

Hon Kate Doust MLC 22 October 2020 Dr Andrew Robertson CSC PSM Chief Health Officer Department of Health PO Box 8172 Perth Business Centre Perth WA 6849 Via email: [email protected] Dear Dr Robertson Sittings of the Legislative Council - COVID-19 Pandemic Phase 4 (modified) I note the modifications to the WA Roadmap Phase 4 restrictions announced by the State Government on 19 October 2020 that, with effect from 24 October 2020, will now allow exemptions to the 2 square metre rule at selected venues that primarily hold seated events, including theatres, concert halls, auditoriums, amphitheatres, cinemas, comedy lounges and performing arts centres. Consequently, I seek your advice regarding arrangements made for sittings of the Legislative Council from 3 November 2020. Since 31 March 2020, Members and staff working in the Legislative Council chamber have operated under modified seating and speaking arrangements, and procedures to ensure social distancing that minimise the risk presented by the COVID-19 pandemic. I enclose plans of the Legislative Council chamber showing its dimensions and pre-COVID-19 and current seating plans together with a list of COVID-19 measures in place for chamber operations. The Legislative Council will undertake its examination of the 2019- 20 estimates of revenue and expenditure in November in the Legislative Council chamber. This will involve numerous public servants being required to attend in the chamber to assist their relevant minister. PAR LI AM EN T OF WEST ER N AUSTRA LIA PARLIAMENT H OUSE. HARVEST TERRA C E. PERTH WA 6000 TELEPHONE: ( 08) 9222 72 11 FACSIMILE: (08) 9222 7814 In addition, there is also a possibility that the two Houses of the Parliament of Western Australia will meet at a joint sitting to choose a Senator for Western Australia arising from an expected vacancy in representation that will occur on 30 October 2020. -

«Hon» «Preferred Name» «Surname»

Hon Martin Aldridge, MLC Hon Ken Baston, MLC Hon Liz Behjat, MLC Member for Agricultural Member for Mining and Pastoral Member for North Metropolitan Level 1, Sterling House PO Box 1452 Suite 1, 43 Cedric Street 8 Parliament Place BROOME WA 6725 STIRLING WA 6021 WEST PERTH WA 6005 Hon Jacqui Boydell, MLC Hon Paul Brown, MLC Hon Robin Chapple, MLC Member for Mining and Pastoral Member for Agricultural Member for Mining and Pastoral Level 1, Sterling House Unit 3, 5 Chapman Road PO Box 94 8 Parliament Place GERALDTON WA 6530 WEST PERTH WA 6872 WEST PERTH WA 6005 Hon Jim Chown, MLC Hon Alanna Clohesy, MLC Hon Peter Collier, MLC Member for Agricultural Member for East Metropolitan Member for North Metropolitan 5 Harvest Terrace 62 Eighth Avenue PO Box 2606 WEST PERTH WA 6005 MAYLANDS WA 6051 WARWICK WA 6024 Hon Stephen Dawson, MLC Hon Kate Doust, MLC Hon Phil Edman, MLC Member for Mining and Pastoral Member for South Metropolitan Member for South Metropolitan PO Box 2440 PO Box 577 PO Box 7029 SOUTH HEDLAND WA 6722 VICTORIA PARK WA 6979 SAFETY BAY WA 6169 Hon Sue Ellery, MLC Member for South Metropolitan Hon Brian Ellis, MLC Hon Donna Faragher, MLC Shop 20, Southlands Boulevard Shopping Member for Agricultural Member for East Metropolitan Centre, Cnr Burrendah Boulevard and PO Box 231 Ground Floor, 108 Swan Street Pine Tree Gully Road GERALDTON WA 6531 GUILDFORD WA 6055 WILLETTON WA 6155 Hon Adele Farina, MLC Hon Nick Goiran, MLC Hon Dave Grills, MLC Member for South West Member for South Metropolitan Member for Mining and Pastoral PO Box -

Souvenir Program

SOUVENIR PROGRAM The Office of the Auditor General acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and their cultures, and to Elders both past and present. Auditor General’s message Dear colleagues and special guests diverse backgrounds. As our cultural fabric continues to evolve, we gain perspective I am delighted to welcome you to our through our diversity. All of us seek to celebration of 190 years of the Auditor further strengthen governance by drawing General for Western Australia. on all available knowledge systems, So important is the oversight of government including from the most ancient of cultures. expenditure, Captain Stirling established From the introduction of typewriters and a Board of Counsel and Audit before even comptometers to the use of laptops and landing on shore to build the Swan River smartphones, from auditing only cash Colony. This represented a significant and cheques to now auditing full financial change in the system of governance from statements and entity performance, the that of the first people, the traditional list of changes goes on. We must be custodians of the land. responsive as the needs and expectations From its beginnings as a Board with 3 of our Parliament and the community commissioners (the Harbour Master, continue to evolve. Surveyor-General and Registrar) to a I hope you will enjoy reading more about position now supported by over 170 the history of the Auditor General and the employees and a large number of contract Office in this souvenir program. -

No. 4 Legislative Council Western Australia

Submission No 4 INQUIRY INTO PROCEDURAL FAIRNESS FOR INQUIRY PARTICIPANTS Organisation: Legislative Council Western Australia Name: Hon Kate Doust MLC Date received: 3 November 2017 Appendix 1 — Witnesses Entitlements Access to relevant documents 1.1 A witness has access to any relevant documents in a committee’s possession which are directly relevant to the witness’s evidence to the committee. This entitlement is subject to any order of the committee that a document be kept confidential (e.g. if the document is given a private status). A witness’s general entitlement to access does not prevail over specific orders of the committee in relation to private evidence. The committee is not required to inform a witness of the existence of private evidence. 1.2 If the relevant documents in question are private and if a witness is aware of the document they may request the committee to review any refusal to provide a private document or to make an order to facilitate access. This provision presupposes that the documents in question are not readily available, and that they have not been previously published. In considering whether to grant access to a relevant document, a committee will need to consider a number of matters, which may include but are not limited to the following: • whether provision of a document would breach any undertaking given by the committee in relation to maintaining its confidentiality; • whether provision of a document would breach any applicable law. • the effects of providing a document on a person’s privacy, security, commercial interests, or legal interests of any person; • whether the withholding of a document would unfairly prejudice a person’s capacity to rebut allegations made against them; • whether there are other methods of providing access. -

P6421b-6425A Hon Donna Faragher; Hon Liz Behjat; Hon Kate Doust; Hon Stephen Dawson; Hon Peter Collier; Hon Robyn Mcsweeney; Hon Michael Mischin

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 16 September 2015] p6421b-6425a Hon Donna Faragher; Hon Liz Behjat; Hon Kate Doust; Hon Stephen Dawson; Hon Peter Collier; Hon Robyn McSweeney; Hon Michael Mischin Standing Committee on Legislation — Twenty-eighth Report — “Demise of the Crown” Resumed from 13 August. Motion Hon DONNA FARAGHER: I move — That the report be noted. I was a member of the committee that participated in the twenty-eighth report, “Demise of the Crown”, and I would just like to make a few comments. By way of background and to remind members, the committee was referred this inquiry as a result of a report by the Standing Committee on Uniform Legislation and Statutes Review, which recommended that legislation be introduced specifically to deal with the demise of the Crown. That report was in response to the referral of the Succession to the Crown Bill 2014 to the Standing Committee on Uniform Legislation and Statutes Review. Members may recall that when the report was returned to the house and debate ensued in respect of that particular bill, there were perhaps diverging opinions on whether or not such legislation was actually required. To assist the consideration of that bill, it was determined that the matter be referred to the legislation committee. Can I say, as a member of that committee, that we deal with interesting pieces of legislation and this was particularly so; it was not something that we would ordinarily deal with, but for members who have not read this very good report, the committee identified that — Imperial law, if it applied in Western Australia, would have the effect of requiring Parliament to prorogue within six months of the demise of the Crown.