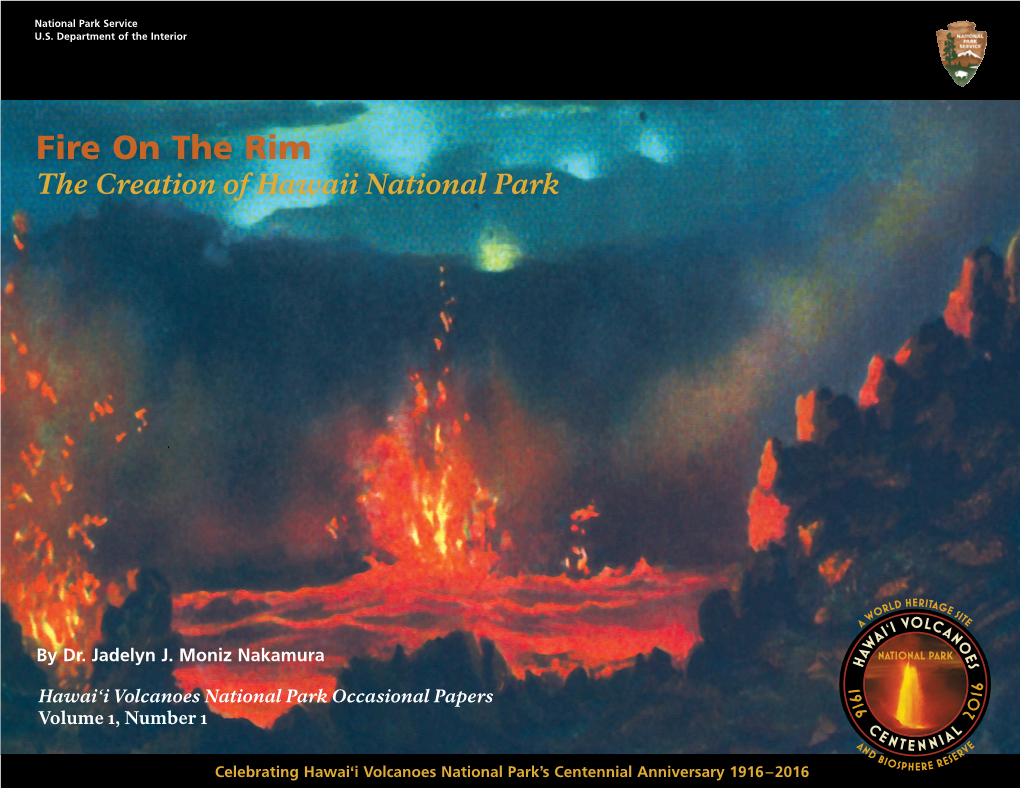

Fire on the Rim: the Creation of Hawaii National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life in Mauna Kea's Alpine Desert

Life in Mauna Kea’s by Mike Richardson Alpine Desert Lycosa wolf spiders, a centipede that preys on moribund insects that are blown to the summit, and the unique, flightless wekiu bug. A candidate for federal listing as an endangered species, the wekiu bug was first discovered in 1979 by entomologists on Pu‘u Wekiu, the summit cinder cone. “Wekiu” is Hawaiian for “topmost” or “summit.” The wekiu bug belongs to the family Lygaeidae within the order of insects known as Heteroptera (true bugs). Most of the 26 endemic Hawaiian Nysius species use a tube-like beak to feed on native plant seed heads, but the wekiu bug uses its beak to suck the hemolymph (blood) from other insects. High above the sunny beaches, rocky coastline, Excluding its close relative Nysius a‘a on the nearby Mauna Loa, the wekiu bug and lush, tropical forests of the Big Island of Hawai‘i differs from all the world’s 106 Nysius lies a unique environment unknown even to many species in its predatory habits and unusual physical characteristics. The bug residents. The harsh, barren, cold alpine desert is so possesses nearly microscopically small hostile that it may appear devoid of life. However, a wings and has the longest, thinnest legs few species existing nowhere else have formed a pre- and the most elongated head of any Lygaeid bug in the world. carious ecosystem-in-miniature of insects, spiders, The wekiu bug, about the size of a other arthropods, and simple plants and lichens. Wel grain of rice, is most often found under rocks and cinders where it preys diur come to the summit of Mauna Kea! nally (during daylight) on insects and Rising 13,796 feet (4,205 meters) dependent) community of arthropods even birds that are blown up from lower above sea level, Mauna Kea is the was uncovered at the summit. -

Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003

“Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Plan of encampment on Mauna Loa summit illustrated by C. Wilkes, Engraved by N. Gimbrede (Wilkes 1845; vol. IV:155) Prepared by Dennis Dougherty B.A., Project Director Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph. D. Principal Investigator Pacific Island Cluster Publications in Anthropology #4 National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park Department of the Interior 2004 “Giant of the Pacific” Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Prepared by Dennis Dougherty, B.A. Edited by J. Moniz-Nakamura, Ph.D. National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park P.O. Box 52 Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 November, 2004 Mauna Loa Reconnaissance 2003 Executive Summary and Acknowledgements The Mauna Loa Reconnaissance project was designed to generate archival and inventory/survey level recordation for previously known and unknown cultural resources within the high elevation zones (montane, sub-alpine, and alpine) of Mauna Loa. Field survey efforts included collecting GPS data at sites, preparing detailed site plan maps and feature descriptions, providing site assessment and National Register eligibility, and integrating the collected data into existing site data bases within the CRM Division at Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HAVO). Project implementation included both pedestrian transects and aerial transects to accomplish field survey components and included both NPS and Research Corporation University of Hawaii (RCUH) personnel. Reconnaissance of remote alpine areas was needed to increase existing data on historic and archeological sites on Mauna Loa to allow park managers to better plan for future projects. The reconnaissance report includes a project introduction; background sections including physical descriptions, cultural setting overview, and previous archeological studies; fieldwork sections describing methods, results, and feature and site summaries; and a section on conclusions and findings that provide site significance assessments and recommendations. -

THE HAWAIIAN-EMPEROR VOLCANIC CHAIN Part I Geologic Evolution

VOLCANISM IN HAWAII Chapter 1 - .-............,. THE HAWAIIAN-EMPEROR VOLCANIC CHAIN Part I Geologic Evolution By David A. Clague and G. Brent Dalrymple ABSTRACT chain, the near-fixity of the hot spot, the chemistry and timing of The Hawaiian-Emperor volcanic chain stretches nearly the eruptions from individual volcanoes, and the detailed geom 6,000 km across the North Pacific Ocean and consists of at least etry of volcanism. None of the geophysical hypotheses pro t 07 individual volcanoes with a total volume of about 1 million posed to date are fully satisfactory. However, the existence of km3• The chain is age progressive with still-active volcanoes at the Hawaiian ewell suggests that hot spots are indeed hot. In the southeast end and 80-75-Ma volcanoes at the northwest addition, both geophysical and geochemical hypotheses suggest end. The bend between the Hawaiian and .Emperor Chains that primitive undegassed mantle material ascends beneath reflects a major change in Pacific plate motion at 43.1 ± 1.4 Ma Hawaii. Petrologic models suggest that this primitive material and probably was caused by collision of the Indian subcontinent reacts with the ocean lithosphere to produce the compositional into Eurasia and the resulting reorganization of oceanic spread range of Hawaiian lava. ing centers and initiation of subduction zones in the western Pacific. The volcanoes of the chain were erupted onto the floor of the Pacific Ocean without regard for the age or preexisting INTRODUCTION structure of the ocean crust. Hawaiian volcanoes erupt lava of distinct chemical com The Hawaiian Islands; the seamounts, hanks, and islands of positions during four major stages in their evolution and the Hawaiian Ridge; and the chain of Emperor Seamounts form an growth. -

Hawaiian Hotspot

V51B-0546 (AGU Fall Meeting) High precision Pb, Sr, and Nd isotope geochemistry of alkalic early Kilauea magmas from the submarine Hilina bench region, and the nature of the Hilina/Kea mantle component J-I Kimura*, TW Sisson**, N Nakano*, ML Coombs**, PW Lipman** *Department of Geoscience, Shimane University **Volcano Hazard Team, USGS JAMSTEC Shinkai 6500 81 65 Emperor Seamounts 56 42 38 27 20 12 5 0 Ma Hawaii Islands Ready to go! Hawaiian Hotspot N ' 0 3 ° 9 Haleakala 1 Kea trend Kohala Loa 5t0r6 end Mauna Kea te eii 95 ol Hualalai Th l 504 na io sit Mauna Loa Kilauea an 509 Tr Papau 208 Hilina Seamont Loihi lic ka 209 Al 505 N 98 ' 207 0 0 508 ° 93 91 9 1 98 KAIKO 99 SHINKAI 02 KAIKO Loa-type tholeiite basalt 209 Transitional basalt 95 504 208 Alkalic basalt 91 508 0 50 km 155°00'W 154°30'W Fig. 1: Samples obtained by Shinkai 6500 and Kaiko dives in 1998-2002 10 T-Alk Mauna Kea 8 Kilauea Basanite Mauna Loa -K M Hilina (low-Si tholeiite) 6 Hilina (transitional) Hilina (alkali) Kea Hilina (basanite) 4 Loa Hilina (nephelinite) Papau (Loa type tholeiite) primary 2 Nep Basaltic Basalt andesite (a) 0 35 40 45 50 55 60 SiO2 Fig. 2: TAS classification and comparison of the early Kilauea lavas to representative lavas from Hawaii Big Island. Kea-type tholeiite through transitional, alkali, basanite to nephelinite lavas were collected from Hilina bench. Loa-type tholeiite from Papau seamount 100 (a) (b) (c) OIB OIB OIB M P / e l p 10 m a S E-MORB E-MORB E-MORB Loa type tholeiite Low Si tholeiite Transitional 1 f f r r r r r r r f d y r r d b b -

Geology, Geochemistry and Earthquake History of Lō`Ihi Seamount, Hawai`I

INVITED REVIEW Geology, Geochemistry and Earthquake History of Lō`ihi Seamount, Hawai`i Michael O. Garcia1*, Jackie Caplan-Auerbach2, Eric H. De Carlo3, M.D. Kurz4 and N. Becker1 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawai`i, Honolulu, HI, USA 2U.S.G.S., Alaska Volcano Observatory, Anchorage, AK, USA 3Department of Oceanography, University of Hawai`i, Honolulu, HI, USA 4Department of Chemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA *Corresponding author: Tel.: 001-808-956-6641, FAX: 001-808-956-5521; email: [email protected] Key words: Loihi, seamount, Hawaii, petrology, geochemistry, earthquakes Abstract A half century of investigations are summarized here on the youngest Hawaiian volcano, Lō`ihi Seamount. It was discovered in 1952 following an earthquake swarm. Surveying in 1954 determined it has an elongate shape, which is the meaning of its Hawaiian name. Lō`ihi was mostly forgotten until two earthquake swarms in the 1970’s led to a dredging expedition in 1978, which recovered young lavas. This led to numerous expeditions to investigate the geology, geophysics, and geochemistry of this active volcano. Geophysical monitoring, including a real- time submarine observatory that continuously monitored Lō`ihi’s seismic activity for three months, captured some of the volcano’s earthquake swarms. The 1996 swarm, the largest recorded in Hawai`i, was preceded by at least one eruption and accompanied by the formation of a ~300-m deep pit crater, renewing interest in this submarine volcano. Seismic and petrologic data indicate that magma was stored in a ~8-9 km deep reservoir prior to the 1996 eruption. -

Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons All Theses & Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840 Anatole Brown MA University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd Part of the Other American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Anatole MA, "Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840" (2014). All Theses & Dissertations. 62. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/62 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL ENCOUNTERS AND THE MISSIONARY POSITION: NEW ENGLAND’S SEXUAL COLONIZATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, 1778–1840 ________________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF THE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES BY ANATOLE BROWN _____________ 2014 FINAL APPROVAL FORM THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES June 20, 2014 We hereby recommend the thesis of Anatole Brown entitled “Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England’s Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778 – 1840” Be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Professor Ardis Cameron (Advisor) Professor Kent Ryden (Reader) Accepted Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been churning in my head in various forms since I started the American and New England Studies Masters program at The University of Southern Maine. -

Mission Stations

Mission Stations The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), based in Boston, was founded in 1810, the first organized missionary society in the US. One hundred years later, the Board was responsible for 102-mission stations and a missionary staff of 600 in India, Ceylon, West Central Africa (Angola), South Africa and Rhodesia, Turkey, China, Japan, Micronesia, Hawaiʻi, the Philippines, North American native American tribes, and the "Papal lands" of Mexico, Spain and Austria. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries set sail on the Thaddeus to establish the Sandwich Islands Mission (now known as Hawai‘i). Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820- 1863 - the “Missionary Period”), about 180-men and women in twelve Companies served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the ABCFM in the Hawaiian Islands. One of the earliest efforts of the missionaries, who arrived in 1820, was the identification and selection of important communities (generally near ports and aliʻi residences) as “Stations” for the regional church and school centers across the Hawaiian Islands. As an example, in June 1823, William Ellis joined American Missionaries Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop and Joseph Goodrich on a tour of the island of Hawaiʻi to investigate suitable sites for mission stations. On O‘ahu, locations at Honolulu (Kawaiahaʻo), Kāne’ohe, Waialua, Waiʻanae and ‘Ewa served as the bases for outreach work on the island. By 1850, eighteen mission stations had been established; six on Hawaiʻi, four on Maui, four on Oʻahu, three on Kauai and one on Molokai. Meeting houses were constructed at the stations, as well as throughout the district. -

Hula: Kalākaua Breaks Cultural Barriers

Reviving the Hula: Kalākaua Breaks Cultural Barriers Breaking Barriers to Return to Barrier to Cultural Tradition Legacy of Tradition Tradition Kalākaua Promotes Hula at His Thesis Tourism Thrives on Hula Shows In 1830, Queen Kaʻahumanu was convinced by western missionaries to forbid public performances of hula Coronation Hula became one of the staples of Hawaiian tourism. In the islands, tourists were drawn to Waikiki for the which led to barriers that limited the traditional practice. Although hula significantly declined, King Kalākaua David Kalākaua became king in 1874 and at his coronation on February 12, 1883 he invited several hālau (hula performances, including the famed Kodak Hula Show in 1937. broke cultural barriers by promoting public performances again. As a result of Kalākaua’s promotion of hula, schools) to perform. Kalākaua’s endorsement of hula broke the barrier by revitalizing traditional practices. its significance remains deeply embedded within modern Hawaiian society. “The orientation of the territorial economy was shifting from agribusiness to new crops of tourists...Hawaiian culture- particularly Hawaiian music and hula-became valued commodities… highly politicized, for whoever brokered the presentation of Hawaiian culture would determine the development of tourism in Hawaii.” “His Coronation in 1883 and jubilee “The coronation ceremony took place at the newly Imada, Adria. American Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 1, Mar. 2004 celebration in 1886 both featured hula rebuilt Iolani Palace on February 12, 1883. The festivities then continued for two weeks thereafter, concluding performances.” “In 1937, Fritz Herman founded the Kodak Hula Show, a performance venue feasts hosted by the king for the people and nightly "History of Hula." Ka `Imi Na'auao O Hawaii Nei Institute. -

A76-425 Rex Financial Corporation

BEFORE THE LAND USE COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF HAWAII In the Matter of the Petition ) DOCKET NO. A76-425 of REX FINANCIAL CORPORATION for a Petition to amend the district boundary of property situated at Kilauea, Island ) and County of Kauai, State of Hawaii. DECISION AND ORDER BEFORE THE LAND USE COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF HAWAII In the Matter of the Petition ) DOCKET NO. A76-425 of REX FINANCIAL CORPORATION for a Petition to amend the district boundary of property situated at Kilauea, Island and County of Kauai, State of Hawaii. DECISION THE PETITION This case arises out of a petition for amendment to the Land Use Commission district boundary classification filed pursuant to Section 205-4, Hawaii Revised Statutes, as amended, by the fee owners of the property who are requesting that their property district designation be amended from Agricultural to Urban. The property in question consists of approximately 35.72 acres and is situated at Kilauea, Island and County of Kauai, State of Hawaii. The Kauai Tax Map Key designation for the subject property is 5—2—04: por. 8. THE PROCEDURAL HISTORY The petition was originally received by the Land Use Commission on December 10, 1976. Due notice of the hearing was published in the Garden Island News and the Honolulu Advertiser on April 13, 1977. Notice of hearing was also sent by certified mail to all of the parties to this docket on April 12, 1977. A prehearing conference on this petition was held on May 13, 1977, for purposes of allowing the parties in this docket to exchange exhibits and lists of witnesses which were to be used or called during the hearing. -

Chemistry of Kilauea and Mauna Loa Lava in Space and Time

"JflK 8 B72 Branch of Chemistry of Kilauea and Mauna Loa Lava in Space and Time GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 735 Chemistry of Kilauea and Mauna Loa Lava in Space and Time By THOMAS L. WRIGHT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 735 An account of the chemical composition of lavas from Kilauea and Mauna Loa volcanoes. Hawaii, and an interpretation of the processes of partial melting and subsequent fractional crystallization that produced the chemical variability UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1971 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS G. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. A. Radlinski, A cting Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-178247 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Price 50 cents (paper.cover) Stock number 2401-1185 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ 1 Observations Continued Introduction _____________________________________ 1 Olivine-controlled lavas _________________ 16 Acknowledgments ________________________________ 2 Petrography __________ __ 16 Definitions and terminology _______________________ 2 Chemistry _______________________ 16 Tholeiite ____________________________________ 2 Differentiated lavas ______ _ ___ 23 Mineral control lines _________________________ 4 Chemical variation within Kilauea lava and differ Olivine-controlled and differentiated basalt _____ 4 ence between Kilauea and Mauna Loa lavas____ 23 Previous work ___________________________________ 5 -

Activities/Attractions Business Name Island Open/Closed Projected

Activities/Attractions Business Name Island Open/Closed Projected Reopening Air Ventures Hawaii Kaua‘i Temporarily Closed TBD Alii Kauai Air Tours & Charters Kaua‘i Open Aloha with Touch Kauai Kaua‘i Open Anaina Hou Community Park Kaua‘i Open Anara Spa Kaua‘i Open Apex Charters Kaua‘i Open Aulii Luau Kaua‘i Temporarily Closed TBD Best of Kauai Tour Kaua‘i Open Blue Dolphin Charters Kaua‘i Open Blue Hawaiian Helicopters Kaua‘i Open Blue Ocean Adventure Tours Kaua‘i Open Bubbles Below Scuba Charters Kaua‘i Open Captain Andy's Sailing Adventures Kaua‘i Open Catamaran Kahanu Kaua‘i Open CJM Country Stables, Inc. Kaua‘i Open Common Ground Kauai Kaua‘i Open CrossFit Poipu Kaua‘i Open Da Life Outdoors Kaua‘i Open Deep Sea Fishing Kauai Kaua‘i Open Dolphin Touch Wellness Center Kaua‘i Open Eco eBikes Kauai Kaua‘i Open Garden Island Chocolate Kaua‘i Open GetYourGuide Kaua‘i Open Go Fish Kauai Kaua‘i Open Grand Hyatt Kauai Luau Kaua‘i Temporarily Closed TBD Grove Farm Museum Kaua‘i Open Halele'a Spa Kaua‘i Temporarily Closed 2022 Hanalei Spirits Distillery Corp Kaua‘i Open Holo Holo Charters Kaua‘i Open Ho'opulapula Haraguchi Rice Mill Kaua‘i Temporarily Closed TBD Hunt Fish Kauai Kaua‘i Open Island Gym & Fitness Kaua‘i Open Island Helicopters Kauai, Inc. Kaua‘i Open Jack Harter Helicopters Kaua‘i Open Kauai Athletic Club-Lihue & Kapaa Kaua‘i Open Kauai ATV Kaua‘i Open Kauai Backcountry Adventures Kaua‘i Open Kauai Beach Boys Kaua‘i Open Kauai Bound Kaua‘i Open Kauai Coffee Company Visitor Center Kaua‘i Open Kauai CrossFit Kaua‘i Open Kauai Eco -

Hawaiÿi Newspaper Indexes

quick start guides Hawai ÿi Newspaper Indexes TM Subject and keyword access to news articles from the Advertiser and Star-Bulletin @ your library News stories from the staff writers of the Honolulu Advertiser and the Star-Bulletin dating back to 1929 can be identified using print and electronic indexes. The Indexes and their years of coverage ___________________________________________________ Index to the Honolulu Advertiser and Honolulu Star-Bulletin Honolulu Advertiser Home Page 1929 – 1994 1999 October – present Hawaii Newspaper Index via the Hawaii State Library Honolulu Star-Bulletin Home Page (Includes both the Advertiser and Star-Bulletin ) 1989 – present 1996 March – present Coverage by date ___________________________________________________ 1929-1988 Index to the Honolulu Advertiser and Honolulu Star-Bulletin only 1989-1994 Index to the Honolulu Advertiser and Honolulu Star-Bulletin ; Hawaii Newspaper Index 1995-1996 Feb Hawaii Newspaper Index only 1996 Mar - 1999 Sept Hawaii Newspaper Index ; Star-Bulletin Home Page 1999 Oct - Present Hawaii Newspaper Index ; Star-Bulletin Home Page ; Honolulu Advertiser Home Page Access ___________________________________________________ Index to the Honolulu Advertiser and Honolulu Star-Bulletin Hamilton Main Reference, 1 st Floor 1929 – 1994 Call number: AI21 .H6 I5 Hamilton Hawaiian, 5 th Floor Call number: AI21 .H6 I5 In a web browser, go to: Hawaii Newspaper Index http://ipac2.librarieshawaii.org:81/ 1989 – present Or start from Hawaii State Public Library System http://www.librarieshawaii.org/