“Perpetual Check” by Samara Kanegis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules & Regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE

Rules & regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship cycle 2012-2014 1. Organisation 1. 1 The Candidates Tournament to determine the challenger for the 2014 World Chess Championship Match shall be organised in the first quarter of 2014 and represent an integral part of the World Chess Championship regulations for the cycle 2012- 2014. Eight (8) players will participate in the Candidates Tournament and the winner qualifies for the World Chess Championship Match in the first quarter of 2014. 1. 2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1. 3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the Candidates Tournament, including internet rights. These rights can be transferred to the organiser upon agreement. 1. 4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 1. 5 At any time in the course of the application of these Regulations, any circumstances that are not covered or any unforeseen event shall be referred to the President of FIDE for final decision. 2. Qualification for the 2014 Candidates Tournament The players who qualify for the Candidates Tournament are determined according to the following, in order of priority: 2. 1 World Championship Match 2013 - The player who lost the 2013 World Championship Match qualifies. 2. 2 World Cup 2013 - The two (2) top winners of the World Cup 2013 qualify. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

An Arbiter's Notebook

Fifty-move Confusion Visit Shop.ChessCafe.com for the largest selection of chess books, sets, and clocks in Question Hello, Geurt. Nowadays there is no specific rule for a draw by North America: perpetual check. Yet somehow I remember there being one; where you could claim a draw by showing the arbiter that you could keep checking whatever the opponent did against any legal move. My memory is that the rule was scrapped just a few years ago, because threefold repetition and the fifty-move rule are good enough. After a bit of Googling around, I noticed firstly that the rule was removed much earlier than I could possibly remember (in the fifties?) and secondly that nobody seems to know when exactly it happened. Do you know when the rule was An Arbiter’s removed from the Laws of Chess? Are there older versions of the Laws available online somewhere? Thank you very much, Remco Gerlich Notebook (The Netherlands) Answer I am not sure whether perpetual check was ever included in the Chess Informant 85 Geurt Gijssen Laws of Chess. Kazic’s The Chess Competitor’s Handbook, published in Only .99 cents! 1980, does not mention it. But there is a very interesting item in this Handbook, which was dates back to 1958: FIDE INTERPRETATION ART 12.4 (1958A) Question: Can a player lose the game by exceeding the time-limit when the position is such that no mate is possible, whatever continuation the players may employ (this concerns Part II of the Laws)? Answer: The Commission declares that the Laws must be interpreted in such a way that in this case, as in the case of perpetual check, a draw cannot be decreed against the will of one of the players before the situation in Article 12.4 is attained. -

The Truth About Chess Rating 1 the Rating Expectation Function

The Truth about Chess Rating Vladica Andreji´c University of Belgrade, Faculty of Mathematics, Serbia email: [email protected] 1 The Rating Expectation Function The main problem of chess rating system is to determine the f function, which assigns probability to rating difference i.e. to the expected result. It actually means that if the player A whose rating is RA plays N games against the player B whose rating is RB, one can expect that A will score N · f(RA − RB) points i.e. final ratio of points in the match where A plays against B will be f(RA − RB): f(RB − RA), where f(RB − RA) = 1 − f(RA − RB). Behaviour of chess rating depends on the f function whose features can be observed in the simplest nontrivial case of extensive series of games played between three players A, B and C. In case that we know the final score of the match between A and B as well as the score of the match where B plays against C, will it be possible to predict the score of the match where A plays against C? One of potential hypotheses is that the nature of rating system preserves established ratios. It actually means that if A and B play, and the result is consistent with a : b ratio, and B and C play and the result is consistent with b : c ratio, we expect A and C to play so that the result is consistent with a : c ratio. If we introduce x and y to respectively denote the rating difference between A and B, and B and C, the hypothesis could be expressed as the following functional equation (f(x + y)) : (1 − f(x + y)) = (f(x)f(y)) : ((1 − f(x))(1 − f(y))); (1) that is valid for each real x and y. -

Art. I.—On the Persian Game of Chess

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— On the Persian Game of Chess. By K BLAND, ESQ., M.R.A.S. [Read June 19th, 1847.] WHATEVER difference of opinion may exist as to the introduction of Chess into Europe, its Asiatic origin is undoubted, although the question of its birth-place is still open to discussion, and will be adverted to in this essay. Its more immediate design, however, is to illustrate the principles and practice of the game itself from such Oriental sources as have hitherto escaped observation, and, especially, to introduce to particular notice a variety of Chess which may, on fair grounds, be considered more ancient than that which is now generally played, and lead to a theory which, if it should be esta- blished, would materially affect our present opinions on its history. In the life of Timur by Ibn Arabshah1, that conqueror, whose love of chess forms one of numerous examples among the great men of all nations, is stated to have played, in preference, at a more complicated game, on a larger board, and with several additional pieces. The learned Dr. Hyde, in his valuable Dissertation on Eastern Games2, has limited his researches, or, rather, been restricted in them by the nature of his materials, to the modern Chess, and has no further illustrated the peculiar game of Timur than by a philological Edited by Manger, "Ahmedis ArabsiadEe Vitae et Rernm Gestarum Timuri, qui vulgo Tamerlanes dicitur, Historia. Leov. 1772, 4to;" and also by Golius, 1736, * Syntagma Dissertationum, &c. Oxon, MDCCJ-XVII., containing "De Ludis Orientalibus, Libri duo." The first part is " Mandragorias, seu Historia Shahi. -

Akela Chess Classic Tournament Format, Operation, and Rules

AKELA CHESS CLASSIC TOURNAMENT FORMAT, OPERATION, AND RULES Format and Brackets. The tournament is a five-round tournament in two brackets – Tiger/Wolf and Bear/Webelos/Arrow of Light. Brackets are determined by a scout’s “rising” rank, the rank the scout is earning or has earned within the school year of the tournament. Scouts will only compete against other scouts within their own bracket. Knowledge of Rules. Scouts are expected to know the complete rules of chess, including but not limited to: set-up, movement and capture-movement of the pieces and pawns, castling, en passant capture, pawn promotion, check and checkmate, and draws (see below for conditions). No instruction is provided at the tournament. Conditions for Draws. Consistent with the rules of chess, a draw may be declared: o If the position is a stalemate (on his move, the scout’s king is not in check but the scout may not legally move, because his pieces and pawns are blocked from moving, and/or he would expose his king to check). o If neither side has sufficient material to force checkmate. o If the same position on the board recurs three times (this provision includes but is not limited to perpetual check). o If 50 consecutive moves have been made by each side with neither a capture nor a pawn move. o Both sides agree to an offered draw, after at least 30 moves have been played by each side. This condition is subject to the Proctor’s review; see below. Touch-Move. The tournament is a touch-move tournament. -

Example of a Checkmate Position Xiangqi Is a Traditional Board Game with Many Similarities to the International Chess

Introduction to Xiangqi World Xiangqi Federation (象棋, Chinese Chess, пиньинь) Email:[email protected] Example of a Checkmate Position Xiangqi is a traditional board game with many similarities to the international chess. Liubo, a kind of predecessor dates back more than 2000 years and the board and pieces used nowadays existed already The following position arises after advancing Red’s Pawn one step towards Black’s King at the end of the Song Dynasty at about 1200. The Board (opening position) The Pieces The basic Rules The Board: 1. the board is set up by 8x8 squares, however, the pieces are positioned on the lines 2. the board is horizontally separated by a “River” 3. on both sides is an area of 2x2 squares marked with a diagonal cross, the “Palace” The aim of the game: Set the King of the opponent checkmate or stalemate King: The King can move only one step in either horizontal or vertical line. He cannot move outside the Palace. As in international chess he is not permitted to step on a position which is under impact of an opponent’s piece. The Kings may not face each other in the same file! Therefore, a King might exert a similar long range power as a Rook. Rook: The Rook moves –as in international chess- along horizontal or vertical lines as long as the path is Explanation: not occupied by a piece; if the blocking piece belongs to the opponent it might be captured, whereas the own piece cannot be removed. Black’s King is attacked by Red’s Pawn (check) Cannon: The Cannon moves similar as the Rook on horizontal and vertical lines. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

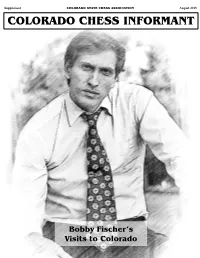

Bobby Fischer's Visits to Colorado – Colorado Chess Informant

Supplement COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION August 2018 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Bobby Fischer’s Visits to Colorado Supplement Colorado Chess Informant August 2018 COLORADO CHESS HISTORY - BOBBY FISCHER’S VISITS by National Master Todd Bardwick This supplement to the Informant is an attempt to give a detailed historical account of Bobby Fischer’s visits to Colorado for current and future generations. I have written many articles about it in the Rocky Mountain News over the 17 years I wrote for the newspaper. (To find thoses articles, you can go to www.ColoradoMasterChess.com and click on the Articles link.) This became a much bigger project that I originally anticipated as the list of people to talk to grew. It became a real life “Searching for Bobby Fischer”, just 47 years later. My research on the subject started back in the early to mid 1990s while visiting John Howell. John’s contributions to Colorado chess as an organizer where monumental. I realized that the stories he told were of huge historical significance to the history of Colorado chess. Today, I wish my notes of our conversations were even more detailed and, looking back, there is a lot more I would like to ask him. John passed away on March 7, 2000 at the age of 88. Cathy Howell, John’s daughter, recently helped me to fill in some of the blanks, provided a copy of some of the notes from John’s diaries (he kept a detailed diary for most days of his adult life!), and gave me chess articles and photos from his files dating back into the 1960s which are posted on the History Section of the Colorado State Chess Association website. -

An Algorithm for the Detection of Move Repetition Without the Use of Hash-Keys

Yugoslav Journal of Operations Research 17 (2007), Number 2, 257-274 DOI: 10.2298/YUJOR0702257V AN ALGORITHM FOR THE DETECTION OF MOVE REPETITION WITHOUT THE USE OF HASH-KEYS Vladan VUČKOVIĆ, Đorđe VIDANOVIĆ Faculty of Electronic Engineering Faculty of Philosophy University of Niš, Serbia Received: July 2006 / Accepted: September 2007 Abstract: This paper addresses the theoretical and practical aspects of an important problem in computer chess programming – the problem of draw detection in cases of position repetition. The standard approach used in the majority of computer chess programs is hash-oriented. This method is sufficient in most cases, as the Zobrist keys are already present due to the systemic positional hashing, so that they need not be computed anew for the purpose of draw detection. The new type of the algorithm that we have developed solves the problem of draw detection in cases when Zobrist keys are not used in the program, i.e. in cases when the memory is not hashed. Keywords: Theory of games, algorithms in computer chess, repetition detection. 1. INTRODUCTION The solution to the problem of move repetition detection is important for the creation of a computer chess playing program that follows and implements all official rules of chess in its search [2], [5]. Namely, in accordance with the official rules of chess there are two major types of positions in which a draw is proclaimed: (a) when the position in which the same side to move has been repeated three times in the course of a game and (b) when no capture has been made or no pawns have been moved during the last fifty consecutive moves. -

Chess Has Been Around for About 1500 Years

Chess Rules! An Ancient Game Chess was invented somewhere in India or the Middle East 1500- 2000 years ago. It was already an old, OLD game during the times of the castles, kings, and knights in Europe. A thousand years ago, Arabians brought a version of chess to Europe. The rules were different then, and it took several days to play a single game! It took another 500 years for the game to slowly change into the version we play now. In the past 500 years, the rules have hardly changed at all. A Great Game There's a reason why it has survived so long—it's a great game! Chess has way more strategy than most games. A well-played game is a work of art. To play the game well requires planning, creativity, thinking ahead, logic, calculation, and patience. Playing chess is a fun way to exercise your brain muscles. The Chessboard A game of chess is a battle of 8 minds fought on a battlefield with an 8 8 array of light and dark 7 squares. Each square has a name 6 that tells you where it is on the board. For example, the square b3 5 is on the b-file and the third rank. Can you locate the e5 and f2 4 squares? 3 b3 Most of the time when you play 2 games of chess, you won't be 1 thinking about the names of the squares, but you will need to a b c d e f g h know them if you want to talk about and learn about chess. -

12 Puzzles Per Page (Sometimes Less Because of a Drawing) – 1 Reminder

Workbook: Learning Chess Step 6 112 pages: 110 different exercises – 12 puzzles per page (sometimes less because of a drawing) – 1 reminder Contents 1 Step 6 57 Bishop endings (same coloured) / Technique: A 2 Attacking the king / King in the middle: A 58 Bishop endings (opposite coloured) / Passed pawn: A 3 Attacking the king / King in the middle: B 59 Bishop endings (opposite coloured) / Defending: A 4 Endgame / Passed pawn: A 60 Bishop endings (same coloured) / Defending: A 5 Endgame / Passed pawn: B 61 Defending / Defending against an attack on the king: A 6 Middlegame / Passed pawn: A 62 Defending / Defending against an attack on the king: B 7 Endgame / Pawn against knight: A 63 Defending / Piece against a passed pawn ( ): A 8 Endgame / Pawn against bishop: A 64 Defending / Defending against tactics: A 9 Strategy / Mini plan: A 65 Rook endings / Activity and vulnerability: A 10 Strategy / Mini plan: B 66 Rook endings / Passed pawn: A 11 Strategy / Mini plan: C 67 Rook endings / Passed pawn: B 12 Strategy / Mini plan: D 68 Rook endings / Technique: A 13 Mobility / Trapping: A 69 Rook endings / Technique: B 14 Mobility / Trapping: B 70 Rook endings / Rook in front of the pawn: A 15 Mobility / Trapping (queen b2/b7): C 71 Search and solving strategies 16 Mobility / Trapping (double attack): D 72 Mate / Mating patterns ( ): A 17 Draw / Perpetual check: A 73 Mate / Mating patterns ( ): B 18 Draw / Stalemate: A 74 Mate / Mating patterns ( ): C 19 Draw / Defending against a passed pawn: A 75 Mate / Mating patterns (back rank): D 20 Draw