A Problem with No Solution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules & Regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE

Rules & regulations for the Candidates Tournament of the FIDE World Championship cycle 2012-2014 1. Organisation 1. 1 The Candidates Tournament to determine the challenger for the 2014 World Chess Championship Match shall be organised in the first quarter of 2014 and represent an integral part of the World Chess Championship regulations for the cycle 2012- 2014. Eight (8) players will participate in the Candidates Tournament and the winner qualifies for the World Chess Championship Match in the first quarter of 2014. 1. 2 Governing Body: the World Chess Federation (FIDE). For the purpose of creating the regulations, communicating with the players and negotiating with the organisers, the FIDE President has nominated a committee, hereby called the FIDE Commission for World Championships and Olympiads (hereinafter referred to as WCOC) 1. 3 FIDE, or its appointed commercial agency, retains all commercial and media rights of the Candidates Tournament, including internet rights. These rights can be transferred to the organiser upon agreement. 1. 4 Upon recommendation by the WCOC, the body responsible for any changes to these Regulations is the FIDE Presidential Board. 1. 5 At any time in the course of the application of these Regulations, any circumstances that are not covered or any unforeseen event shall be referred to the President of FIDE for final decision. 2. Qualification for the 2014 Candidates Tournament The players who qualify for the Candidates Tournament are determined according to the following, in order of priority: 2. 1 World Championship Match 2013 - The player who lost the 2013 World Championship Match qualifies. 2. 2 World Cup 2013 - The two (2) top winners of the World Cup 2013 qualify. -

Chess-Training-Guide.Pdf

Q Chess Training Guide K for Teachers and Parents Created by Grandmaster Susan Polgar U.S. Chess Hall of Fame Inductee President and Founder of the Susan Polgar Foundation Director of SPICE (Susan Polgar Institute for Chess Excellence) at Webster University FIDE Senior Chess Trainer 2006 Women’s World Chess Cup Champion Winner of 4 Women’s World Chess Championships The only World Champion in history to win the Triple-Crown (Blitz, Rapid and Classical) 12 Olympic Medals (5 Gold, 4 Silver, 3 Bronze) 3-time US Open Blitz Champion #1 ranked woman player in the United States Ranked #1 in the world at age 15 and in the top 3 for about 25 consecutive years 1st woman in history to qualify for the Men’s World Championship 1st woman in history to earn the Grandmaster title 1st woman in history to coach a Men's Division I team to 7 consecutive Final Four Championships 1st woman in history to coach the #1 ranked Men's Division I team in the nation pnlrqk KQRLNP Get Smart! Play Chess! www.ChessDailyNews.com www.twitter.com/SusanPolgar www.facebook.com/SusanPolgarChess www.instagram.com/SusanPolgarChess www.SusanPolgar.com www.SusanPolgarFoundation.org SPF Chess Training Program for Teachers © Page 1 7/2/2019 Lesson 1 Lesson goals: Excite kids about the fun game of chess Relate the cool history of chess Incorporate chess with education: Learning about India and Persia Incorporate chess with education: Learning about the chess board and its coordinates Who invented chess and why? Talk about India / Persia – connects to Geography Tell the story of “seed”. -

Benko 90 JT the Provisional Award XABCDEFGHY 8-+-+-+

Benko 90 JT The provisional award In the tournament invitation we wrote Pal Benko as judge. Unfortunately he had to hand over this role to someone else. Benko GM had temporary problems with his sight. Benko chose Richard Becker instead of himself. Richard Becker's judgment report and the award, that I published in the 6/2019 issue of Magyar Sakkvilag . (Peter Gyarmati , tournament director) "To my mind, Pal Benko straddled the chess world like a Colossus; one foot in the world of OTB chess and the other reaching to all the genres of chess composition. His endgame studies are at the highest level of our art. They are filled with novel and counter-intuitive ideas expressed with grandmasterly technique and a degree of economy that truly is pre-computer wizardry. In judging the Pal Benko-90 JT, I tried to reward deep plans and surprise moves, good technique and economy, and anything with a thematic ring to it. From among the 65 studies in anonymous form I received from Peter, I found eleven that satisfied. Upon further review, four studies fell out of competition due to serious duals. These seven remaining studies I recommend as the winners. 1st Prize Jan Timman XABCDEFGHY 8-+-+-+-( 7+-+-++-' 6--+-+-+& 5++-+-+-% 4-+-+-+-$ 3-+-+--# 2+-+-+" 1+-+-+-! xabcdefghy win 1.d1 [The reasonable looking 1.e3+? g4 2.d3 fails to 2... 2...f6! 3.xf6 e7 4.a1 g5=] 1...c1 2.e2 h3 [2...g2 3.d4+-] 3.g1+ [Not 3.c4? g2 4.c5 a3! draw] 3...h2 4.f2 [4.f1? g2=] 4...f6! 5.xf6 b2 6.c3!! [The logical try: 6.xb2 d1+! 7.xd1 a1! 8.h1+ xh1 9.xa1 h2 10.g3 g1 11.d4+ h1 12.c5 bxc5 13.f2 c4 14.b6 c3 and stalemate can no longer be avoided] 6...xc3 7.xc3 d1+ [2nd main line: 7...a1 8.xa1 (8.xa1? d1+! 9.f1 e3+ 10.f2 d1+=) 8...d1+ 9.f1 xc3 10.a5!! zz 10...d5 11.a3 c7 12.b3 d5 13.f2 and wins] 8.xd1 a1 9.h1+! xh1 [9...xh1 10.e5#] 10.xa1 h2 11.g3 g1 12.d4+ h1 13.c5! bxc5 14.f2 c4 15.b6 c3 16.b7 and mates in three. -

An Arbiter's Notebook

Fifty-move Confusion Visit Shop.ChessCafe.com for the largest selection of chess books, sets, and clocks in Question Hello, Geurt. Nowadays there is no specific rule for a draw by North America: perpetual check. Yet somehow I remember there being one; where you could claim a draw by showing the arbiter that you could keep checking whatever the opponent did against any legal move. My memory is that the rule was scrapped just a few years ago, because threefold repetition and the fifty-move rule are good enough. After a bit of Googling around, I noticed firstly that the rule was removed much earlier than I could possibly remember (in the fifties?) and secondly that nobody seems to know when exactly it happened. Do you know when the rule was An Arbiter’s removed from the Laws of Chess? Are there older versions of the Laws available online somewhere? Thank you very much, Remco Gerlich Notebook (The Netherlands) Answer I am not sure whether perpetual check was ever included in the Chess Informant 85 Geurt Gijssen Laws of Chess. Kazic’s The Chess Competitor’s Handbook, published in Only .99 cents! 1980, does not mention it. But there is a very interesting item in this Handbook, which was dates back to 1958: FIDE INTERPRETATION ART 12.4 (1958A) Question: Can a player lose the game by exceeding the time-limit when the position is such that no mate is possible, whatever continuation the players may employ (this concerns Part II of the Laws)? Answer: The Commission declares that the Laws must be interpreted in such a way that in this case, as in the case of perpetual check, a draw cannot be decreed against the will of one of the players before the situation in Article 12.4 is attained. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

The Truth About Chess Rating 1 the Rating Expectation Function

The Truth about Chess Rating Vladica Andreji´c University of Belgrade, Faculty of Mathematics, Serbia email: [email protected] 1 The Rating Expectation Function The main problem of chess rating system is to determine the f function, which assigns probability to rating difference i.e. to the expected result. It actually means that if the player A whose rating is RA plays N games against the player B whose rating is RB, one can expect that A will score N · f(RA − RB) points i.e. final ratio of points in the match where A plays against B will be f(RA − RB): f(RB − RA), where f(RB − RA) = 1 − f(RA − RB). Behaviour of chess rating depends on the f function whose features can be observed in the simplest nontrivial case of extensive series of games played between three players A, B and C. In case that we know the final score of the match between A and B as well as the score of the match where B plays against C, will it be possible to predict the score of the match where A plays against C? One of potential hypotheses is that the nature of rating system preserves established ratios. It actually means that if A and B play, and the result is consistent with a : b ratio, and B and C play and the result is consistent with b : c ratio, we expect A and C to play so that the result is consistent with a : c ratio. If we introduce x and y to respectively denote the rating difference between A and B, and B and C, the hypothesis could be expressed as the following functional equation (f(x + y)) : (1 − f(x + y)) = (f(x)f(y)) : ((1 − f(x))(1 − f(y))); (1) that is valid for each real x and y. -

OPEN CHAMPION (See P

u. S. OPEN CHAMPION (See P. 215) Volume XIX Number \I September, lt64 EDITOR: J. F. Reinhardt U. S. TEAM TO PLAY IN ISRAEL CHESS FEDERATION The United States has formally entered a team in the 16th Chess Olympiad to be played in Tel Aviv, Israel from November 2-24 . PRESIDENT Lt. Col. E. B. Edmo ndson Invitations were sent out to the country's top playcrs In order of tbeir USCF VICE·PRESIDENT David BoUrnaDn ratings. Samuel Reshevsky, Pal Benko, Arthur Bisguier. William Addison, Dr. An thony Saidy and Donald Byrne have all accepted. Grandmaster Isaac Kashdan will REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS NEW ENGLAND StaDle y Kin, accompany tbe tcam as Don-playing captain. H arold Dondl . Robert Goodspeed Unfortunately a number of our strongest players ar e missing from the team EASTERN Donald Sc hu lt ~ LewU E. Wood roster. While Lombardy, Robert Byrne and Evans were unavailable for r easons Pc)ter Berlow that had nothing to do wi th money, U. S. Cham pion Robert Fischer 's demand (or Ceoric Thoma. EII rl Clar y a $5000 fee was (ar more than the American Chess Foundation, which is raiSing Edwa rd O. S t r ehle funds for t his event, was prepared to pay. SOUTHERN Or. Noban Froe'nll:e J erry Suillyan Cu roll M. Cn lll One must assume that Fiscber, by naming 5(J large a figure and by refusing GREAT LAKES Nor bert Malthewt to compromise on it, realized full well that he was keeping himseJ! off the team Donald B. IIUdlng as surely as if be had C{)me out with a !lat "No." For more than a year Fischer "amn Schroe(ier has declined to play in international events to which he bas been invited- the NORTH CENTRAL F rank Skoff John Oane'$ Piatigorsky Tournament, the Intenonal, and now the Olympiad. -

Art. I.—On the Persian Game of Chess

JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— On the Persian Game of Chess. By K BLAND, ESQ., M.R.A.S. [Read June 19th, 1847.] WHATEVER difference of opinion may exist as to the introduction of Chess into Europe, its Asiatic origin is undoubted, although the question of its birth-place is still open to discussion, and will be adverted to in this essay. Its more immediate design, however, is to illustrate the principles and practice of the game itself from such Oriental sources as have hitherto escaped observation, and, especially, to introduce to particular notice a variety of Chess which may, on fair grounds, be considered more ancient than that which is now generally played, and lead to a theory which, if it should be esta- blished, would materially affect our present opinions on its history. In the life of Timur by Ibn Arabshah1, that conqueror, whose love of chess forms one of numerous examples among the great men of all nations, is stated to have played, in preference, at a more complicated game, on a larger board, and with several additional pieces. The learned Dr. Hyde, in his valuable Dissertation on Eastern Games2, has limited his researches, or, rather, been restricted in them by the nature of his materials, to the modern Chess, and has no further illustrated the peculiar game of Timur than by a philological Edited by Manger, "Ahmedis ArabsiadEe Vitae et Rernm Gestarum Timuri, qui vulgo Tamerlanes dicitur, Historia. Leov. 1772, 4to;" and also by Golius, 1736, * Syntagma Dissertationum, &c. Oxon, MDCCJ-XVII., containing "De Ludis Orientalibus, Libri duo." The first part is " Mandragorias, seu Historia Shahi. -

Akela Chess Classic Tournament Format, Operation, and Rules

AKELA CHESS CLASSIC TOURNAMENT FORMAT, OPERATION, AND RULES Format and Brackets. The tournament is a five-round tournament in two brackets – Tiger/Wolf and Bear/Webelos/Arrow of Light. Brackets are determined by a scout’s “rising” rank, the rank the scout is earning or has earned within the school year of the tournament. Scouts will only compete against other scouts within their own bracket. Knowledge of Rules. Scouts are expected to know the complete rules of chess, including but not limited to: set-up, movement and capture-movement of the pieces and pawns, castling, en passant capture, pawn promotion, check and checkmate, and draws (see below for conditions). No instruction is provided at the tournament. Conditions for Draws. Consistent with the rules of chess, a draw may be declared: o If the position is a stalemate (on his move, the scout’s king is not in check but the scout may not legally move, because his pieces and pawns are blocked from moving, and/or he would expose his king to check). o If neither side has sufficient material to force checkmate. o If the same position on the board recurs three times (this provision includes but is not limited to perpetual check). o If 50 consecutive moves have been made by each side with neither a capture nor a pawn move. o Both sides agree to an offered draw, after at least 30 moves have been played by each side. This condition is subject to the Proctor’s review; see below. Touch-Move. The tournament is a touch-move tournament. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

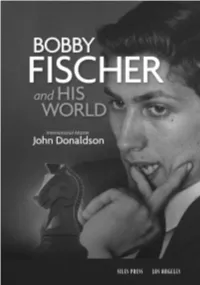

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

Example of a Checkmate Position Xiangqi Is a Traditional Board Game with Many Similarities to the International Chess

Introduction to Xiangqi World Xiangqi Federation (象棋, Chinese Chess, пиньинь) Email:[email protected] Example of a Checkmate Position Xiangqi is a traditional board game with many similarities to the international chess. Liubo, a kind of predecessor dates back more than 2000 years and the board and pieces used nowadays existed already The following position arises after advancing Red’s Pawn one step towards Black’s King at the end of the Song Dynasty at about 1200. The Board (opening position) The Pieces The basic Rules The Board: 1. the board is set up by 8x8 squares, however, the pieces are positioned on the lines 2. the board is horizontally separated by a “River” 3. on both sides is an area of 2x2 squares marked with a diagonal cross, the “Palace” The aim of the game: Set the King of the opponent checkmate or stalemate King: The King can move only one step in either horizontal or vertical line. He cannot move outside the Palace. As in international chess he is not permitted to step on a position which is under impact of an opponent’s piece. The Kings may not face each other in the same file! Therefore, a King might exert a similar long range power as a Rook. Rook: The Rook moves –as in international chess- along horizontal or vertical lines as long as the path is Explanation: not occupied by a piece; if the blocking piece belongs to the opponent it might be captured, whereas the own piece cannot be removed. Black’s King is attacked by Red’s Pawn (check) Cannon: The Cannon moves similar as the Rook on horizontal and vertical lines.