The Story of WANSFORD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Framework Revised.Vp

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology Research and Archaeology Revisited: a revised framework for the East of England edited by Maria Medlycott East Anglian Archaeology Occasional Paper No.24, 2011 ALGAO East of England EAST ANGLIAN ARCHAEOLOGY OCCASIONAL PAPER NO.24 Published by Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers East of England http://www.algao.org.uk/cttees/Regions Editor: David Gurney EAA Managing Editor: Jenny Glazebrook Editorial Board: Brian Ayers, Director, The Butrint Foundation Owen Bedwin, Head of Historic Environment, Essex County Council Stewart Bryant, Head of Historic Environment, Hertfordshire County Council Will Fletcher, English Heritage Kasia Gdaniec, Historic Environment, Cambridgeshire County Council David Gurney, Historic Environment Manager, Norfolk County Council Debbie Priddy, English Heritage Adrian Tindall, Archaeological Consultant Keith Wade, Archaeological Service Manager, Suffolk County Council Set in Times Roman by Jenny Glazebrook using Corel Ventura™ Printed by Henry Ling Limited, The Dorset Press © ALGAO East of England ISBN 978 0 9510695 6 1 This Research Framework was published with the aid of funding from English Heritage East Anglian Archaeology was established in 1975 by the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia. The scope of the series expanded to include all six eastern counties and responsi- bility for publication passed in 2002 to the Association of Local Government Archaeological Officers, East of England (ALGAO East). Cover illustration: The excavation of prehistoric burial monuments at Hanson’s Needingworth Quarry at Over, Cambridgeshire, by Cambridge Archaeological Unit in 2008. -

Catalogue Summer 2012

JONATHAN POTTER ANTIQUE MAPS CATALOGUE SUMMER 2012 INTRODUCTION 2012 was always going to be an exciting year in London and Britain with the long- anticipated Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and the holding of the Olympic Games. To add to this, Jonathan Potter Ltd has moved to new gallery premises in Marylebone, one of the most pleasant parts of central London. After nearly 35 years in Mayfair, the move north of Oxford Street seemed a huge step to take, but is only a few minutes’ walk from Bond Street. 52a George Street is set in an attractive area of good hotels and restaurants, fine Georgian residential properties and interesting retail outlets. Come and visit us. Our summer catalogue features a fascinating mixture of over 100 interesting, rare and decorative maps covering a period of almost five hundred years. From the fifteenth century incunable woodcut map of the ancient world from Schedels’ ‘Chronicarum...’ to decorative 1960s maps of the French wine regions, the range of maps available to collectors and enthusiasts whether for study or just decoration is apparent. Although the majority of maps fall within the ‘traditional’ definition of antique, we have included a number of twentieth and late ninteenth century publications – a significant period in history and cartography which we find fascinating and in which we are seeing a growing level of interest and appreciation. AN ILLUSTRATED SELECTION OF ANTIQUE MAPS, ATLASES, CHARTS AND PLANS AVAILABLE FROM We hope you find the catalogue interesting and please, if you don’t find what you are looking for, ask us - we have many, many more maps in stock, on our website and in the JONATHAN POTTER LIMITED gallery. -

Peterborough's Green Infrastructure & Biodiversity Supplementary

Peterborough’s Green Infrastructure & Biodiversity Supplementary Planning Document Positive Planning for the Natural Environment Consultation Draft January 2018 297 Preface How to make comments on this Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) We welcome your comments and views on the content of this draft SPD. It is being made available for a xxxx week public consultation. The consultation starts at on XX 2018 and closes on XX xxx 2018. The SPD can be viewed at www.peterborough.gov.uk/LocalPlan.There are several ways that you can comment on the SPD. Comments can be made by email to: [email protected] or by post to: Peterborough Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Draft SPD Consultation Sustainable Growth Strategy Peterborough City Council Town Hall Bridge Street Peterborough PE1 1HF All responses must be received by XX xxxx 2018. All comments received will be taken into consideration by the council before a final SPD is adopted later in 2018. 2 298 Contents 1 Introduction 4 Purpose, Status, Structure and Content of the SPD 4 Collaborative working 4 Definitions 5 Benefits of GI 5 Who should think about GI & Biodiversity 7 2 Setting the Scene 8 Background to developing the SPD 8 Policy and Legislation 8 3 Peterborough's Approach to Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity 11 Current Situation 11 Vision 12 Key GI Focus Areas 14 4 Making It Happen - GI Delivery 23 Priority GI Projects 23 Governance 23 Funding 23 5 Integrating GI and Biodiversity with Sustainable Development 24 Recommended Approach to Biodiversity for all Planning -

Nene Valley House

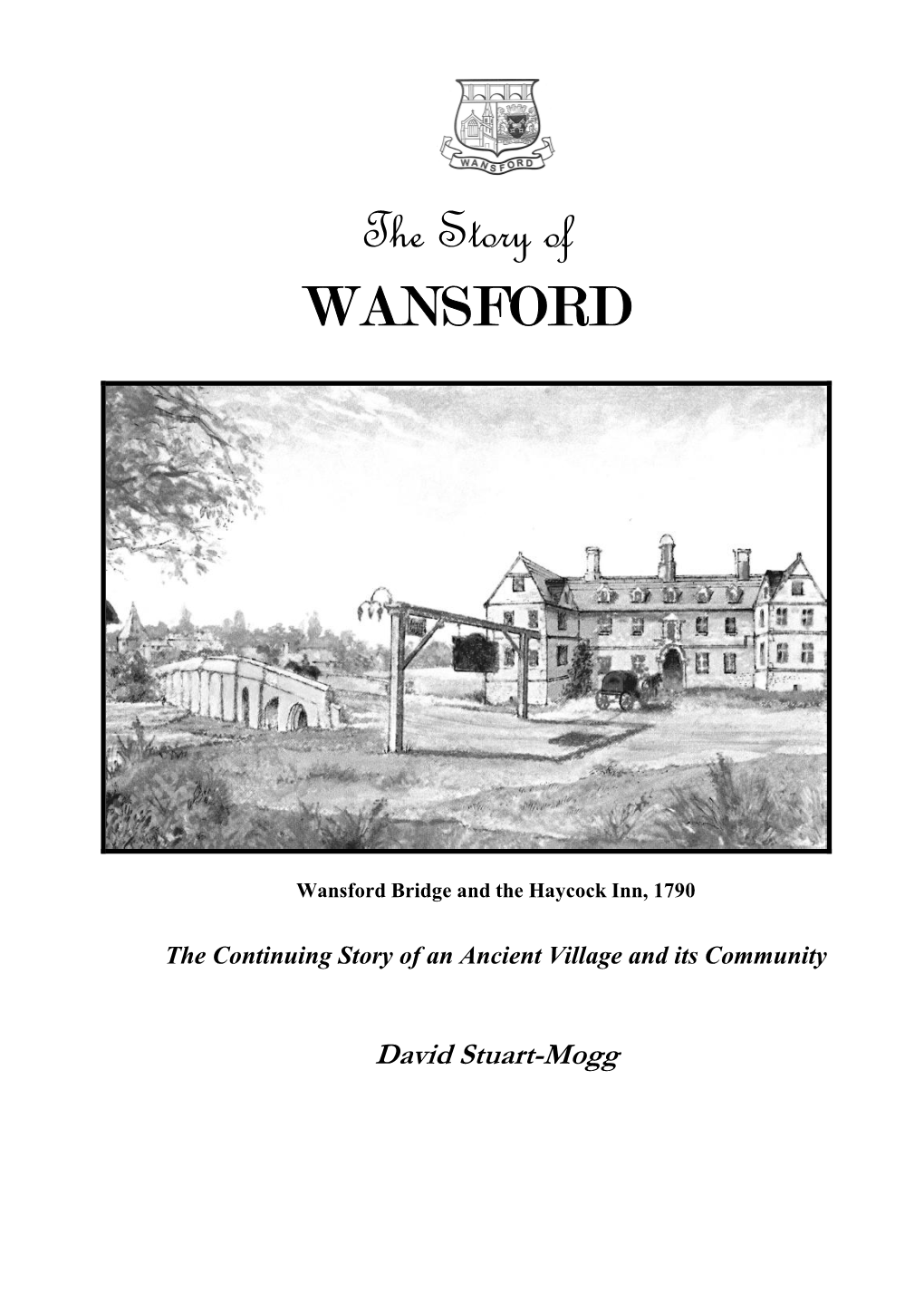

NENE VALLEY HOUSE elton road stibbington peterborough cambridgeshire pe8 6jx A SUBSTANTIAL DETACHED CONTEMPORARY RESIDENCE WITH INDOOR SWIMMING POOL AND OFFICE SUITE, EXTENSIVE GROUNDS WITH FINE VIEWS & GARAGING FOR SIX CARS. nene valley house, elton road, stibbington, peterborough, cambridgeshire, pe8 6jx Entrance & reception hallways three spacious reception rooms kitchen breakfast room principal bedroom suite with balcony & en-suite en-suite guest bedroom two further bedrooms family bathroom two room office suite Gated driveway & turning circle integral triple garage detached triple garage indoor swimming pool landscaped gardens & paddock in all 2 acres, or thereabouts Mileage Stamford 7 miles Oundle & Peterborough 9 miles (rail connections to London Kings Cross & Cambridge from 51 mins) Cambridge 37 miles The Property Constructed in 1990 and offering spacious accommodation of over 6,700 square feet of accommodation as shown on the floor plan, Nene Valley House occupies a glorious and elevated position with westerly views over the River Nene valley. Situation With a Stibbington address, Nene Valley House lies on Elton Road between Wansford (1 mile) and Elton (2.5 miles). Wansford is an attractive village with largely stone period houses, which is bypassed by the A1. The 16th century Haycock Inn is a renowned hotel restaurant, whilst the village also supports two further public houses, a village shop and post office and a doctor’s surgery with pharmacy. Elton is a delightful village with a very traditional core of largely period stone and collyweston properties. It supports a village shop, primary school, cricket club and two public houses, in addition to a Loch Fyne restaurant. -

The Land Army

Stibbington Home Front Memories Project – Part 7 Land Army the Woman’s Role THE LAND ARMY The landgirls carried out a vital role on the farms, and for many, coming from factory work or domestic service, discovering the countryside was quite an eye opener! A whole range of new skills were waiting to be mastered. Clearly, in the early days, adaptations had to be made – one article in the Stamford Mercury in November 1939 declares: ‘It Isn’t Done on the Farm Not Fair to Milk With Pointed Nails Advice For Landgirls’ In May 1940, Lady Spencer visited Sacrewell, Burghley Estate and Fotheringhay Dairy and reported just how much the girls were enjoying their work. In January 1942, the first hostel for landgirls opened in Barnack, and the following extracts give a taste of what life was like for them: [PA 30/1/42] [1] Stibbington Home Front Memories Project – Part 7 Land Army the Woman’s Role [PA 30/1/42] A second hostel for 25 Londoners opened in Newborough later that year, and the previously empty Rectory at Thornhaugh was taken over to house another 26 girls. The girls get a couple of other mentions in the press, once when the Barnack Hostel presented Cinderella, ‘a delightful show’, and again when Evelyn Gamble and Maisie Peacock from Thornhaugh were each fined 2s 6d (12½p) at Norman Cross Court for riding two on one bicycle at Stibbington! OTHER ROLES FOR WOMEN Well before war was declared, women were being prepared for voluntary roles. In June 1939, for example, there was a report of a rally of women drivers at Woodcroft Castle, Etton ‘tests in wheel changing and driving wearing a respirator this week, map reading classes next week’ There were calls in 1940 for women who could ride a bicycle to act as messengers for parachute patrols; details of the Peterborough House WiVeS Service were published, encouraging those women unavailable to volunteer for Civil Defence Services who would however be able to offer help to neighbours in their immediate locality in the event of a raid. -

Agenda December 2020

AILSWORTH PARISH COUNCIL Hibbins Cottage, The Green, Ketton, Stamford. PE9 3RA Email; [email protected] Dear Councillors, Due to the continuing pandemic situation and following a recent change in legislation, Parish Council meetings are permitted to be held remotely. You are therefore requested to remotely “attend” the Parish Council meeting of Ailsworth Parish Council on Monday 21st December 2020 at 7.30pm. A link will be sent via email on the day for you to join the meeting by video conferencing/Zoom. Id 89309456164 passcode 532664 Yours sincerely, Jenny Rice Jenny Rice, Clerk and Responsible Finance Officer A G E N D A 20/128 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE To receive and note apologies received by the Clerk. 20/129 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive all declarations of interest under the Council’s Code of Conduct related to business on the agenda. (Members should disclose any interests (pecuniary, personal or other) in the business to be discussed and are reminded that the disclosure of a Dis- closable Pecuniary Interest will require that the member withdraws from the meeting during the transaction of that item of business). 20/130 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION A maximum of 15 minutes is permitted for members of the public to address the meeting. IF A MEMBER OF THE PUBLIC WISHES TO ATTEND THE MEETING, PLEASE USE THE DETAILS ON THE WEBSITE AND ABOVE TO JOIN VIA ZOOM AND/OR CONTACT THE CLERK FOR HELP OR TO RECEIVE A PHONE CALL TO JOIN VIA PHONE OR SUBMIT ANY QUESTIONS VIA EMAIL BY 7PM ON THE DAY. 20/131 MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING on 16th November 2020 (previously circulated) 20/132 MATTERS ARISING: To note defibrillator process notice put in board and on facebook, general training ses- sion needed when able to do so as confusion over scheme exists. -

Just Dogs Live, East of England Showground, Peterborough, Pe2 6Xe

Present British Flyball Association 48 Team LIMITED OPEN SANCTIONED TOURNAMENT at JUST DOGS LIVE, EAST OF ENGLAND SHOWGROUND, PETERBOROUGH, PE2 6XE on Saturday 10th and Sunday 11th July 2010 Closing date for entries: 10th June 2010 For further information contact: Ellen Schofield Telephone: 01353 659950 / 07725 904831 Address: 43 Briars End, Witchford, Ely, Cambs, CB6 2GB E-mail: [email protected] This tournament is being held alongside the Just Dogs Live Event on the 9th/10th/11th July 2010. Just Dogs Live incorporates the East of England Championship Dog Show and will include the traditional Crufts qualifier showing classes. The show, now in its second year, will also feature additional attractions, including demonstrations and competitions to ensure the event is a fantastic day out for all dog lovers, young and old. Just a selection of the demos, have-a-gos and competitions that are happening are… Laines Shooting School & Mullenscote Gundogs Essex Dog Display Team Canine Partners Pets As Therapy Prison Dog Display Scurry Bandits For more information please see their website - http://www.justdogslive.co.uk/ The area of the showground that is covered by the BFA sanctioned tournament is not part of UK Kennel Club Licensed show, and you are free to come and go within this area as you please. If you wish to visit the main show you are also free to do so, and we will supply you with wrist bands to enable you to enter the show FOC. However, if you wish to take your dog into the KC area of the showground, you will be required to sign a declaration form in accordance with the KC rules. -

The History of Cartography, Volume 3

THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Volume Three Editorial Advisors Denis E. Cosgrove Richard Helgerson Catherine Delano-Smith Christian Jacob Felipe Fernández-Armesto Richard L. Kagan Paula Findlen Martin Kemp Patrick Gautier Dalché Chandra Mukerji Anthony Grafton Günter Schilder Stephen Greenblatt Sarah Tyacke Glyndwr Williams The History of Cartography J. B. Harley and David Woodward, Founding Editors 1 Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean 2.1 Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies 2.2 Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies 2.3 Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies 3 Cartography in the European Renaissance 4 Cartography in the European Enlightenment 5 Cartography in the Nineteenth Century 6 Cartography in the Twentieth Century THE HISTORY OF CARTOGRAPHY VOLUME THREE Cartography in the European Renaissance PART 1 Edited by DAVID WOODWARD THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS • CHICAGO & LONDON David Woodward was the Arthur H. Robinson Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2007 by the University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2007 Printed in the United States of America 1615141312111009080712345 Set ISBN-10: 0-226-90732-5 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90732-1 (cloth) Part 1 ISBN-10: 0-226-90733-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90733-8 (cloth) Part 2 ISBN-10: 0-226-90734-1 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90734-5 (cloth) Editorial work on The History of Cartography is supported in part by grants from the Division of Preservation and Access of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Geography and Regional Science Program and Science and Society Program of the National Science Foundation, independent federal agencies. -

The Official Magazine for RAF Wittering and the A4 Force W in Ter

Winter 2019 Winter WitteringThe official magazine for RAF Wittering and the A4 Force View WINTER 2019 WITTERING VIEW 1 Features: In the Spotlight - Community Support Future • Accommodation Model • Fighting Ovarian Cancer 2 WITTERING VIEW WINTER 2019 WINTER 2019 WITTERING VIEW 3 Editor Welcome to the Winter edition of Foreword the Wittering View. With Autumn now a distant It has been a busy first few memory, and as our thoughts turn months for me. But I wanted to Christmas, we can’t quite believe to start simply by saying thank how quickly this year has gone! you for all the support that RAF Wittering is an incredibly you have given me, as well as to say thank you to all of our busy Station but despite this incredible personnel who have everyone has still found time continued to support both the throughout the year to send in their Station and the A4 (Logistics and articles for which we are grateful. As Engineering) Force Elements. a result, this issue features a good Some of the recent highlights cross-section of the activities taking have included; place here at Wittering. • The Annual Formal Visit by Air From the recent Annual Formal Officer Commanding (AOC) 38 Visit (page 6) and Annual Reception Group, Air Vice-Marshal Simon (page 8) to the various exercises Ellard. The AOC spent 30 hours that Station personnel have been on Station and was able to see involved with (Exercise COBRA the tremendous work that our WARRIOR – page 12 and Exercise personnel from across the Whole JOINT SUPPORTER – page 9), it does Force conduct on a daily basis. -

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials the CD Has Photographs of Almost 90% of the Memorials Plus Information on Their Current Location

PDFHS CD/Download Overview 100 Local War Memorials The CD has photographs of almost 90% of the memorials plus information on their current location. The Memorials - listed in their pre-1970 counties: Cambridgeshire: Benwick; Coates; Stanground –Church & Lampass Lodge of Oddfellows; Thorney, Turves; Whittlesey; 1st/2nd Battalions. Cambridgeshire Regiment Huntingdonshire: Elton; Farcet; Fletton-Church, Ex-Servicemen Club, Phorpres Club, (New F) Baptist Chapel, (Old F) United Methodist Chapel; Gt Stukeley; Huntingdon-All Saints & County Police Force, Kings Ripton, Lt Stukeley, Orton Longueville, Orton Waterville, Stilton, Upwood with Gt Ravely, Waternewton, Woodston, Yaxley Lincolnshire: Barholm; Baston; Braceborough; Crowland (x2); Deeping St James; Greatford; Langtoft; Market Deeping; Tallington; Uffington; West Deeping: Wilsthorpe; Northamptonshire: Barnwell; Collyweston; Easton on the Hill; Fotheringhay; Lutton; Tansor; Yarwell City of Peterborough: Albert Place Boys School; All Saints; Baker Perkins, Broadway Cemetery; Boer War; Book of Remembrance; Boy Scouts; Central Park (Our Jimmy); Co-op; Deacon School; Eastfield Cemetery; General Post Office; Hand & Heart Public House; Jedburghs; King’s School: Longthorpe; Memorial Hospital (Roll of Honour); Museum; Newark; Park Rd Chapel; Paston; St Barnabas; St John the Baptist (Church & Boys School); St Mark’s; St Mary’s; St Paul’s; St Peter’s College; Salvation Army; Special Constabulary; Wentworth St Chapel; Werrington; Westgate Chapel Soke of Peterborough: Bainton with Ashton; Barnack; Castor; Etton; Eye; Glinton; Helpston; Marholm; Maxey with Deeping Gate; Newborough with Borough Fen; Northborough; Peakirk; Thornhaugh; Ufford; Wittering. Pearl Assurance National Memorial (relocated from London to Lynch Wood, Peterborough) Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough (£10) This CD contains a record and index of all the readable gravestones in the Broadway Cemetery, Peterborough. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Alwalton Hall, Alwalton, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire

ALWALTON HALL, ALWALTON, PETERBOROUGH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE ALWALTON HALL CHURCH STREET, ALWALTON, PETERBOROUGH, CAMBRIDGESHIRE An impressive village house believed to have been built for the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam; this Grade II listed property has beautiful proportions and is accompanied by mature gardens, former paddock land and stables extending in all, to approximately 4.05 acres. APPROXIMATE MILEAGES: A1 dual carriageway 0.4 miles • Peterborough train station 5 miles • Stamford 11 miles • Huntingdon train station 17 miles ACCOMMODATION IN BRIEF: Entrance hall, drawing room, sitting room, dining room, TV room, kitchen, breakfast room, snooker room, office, study, utility, inner hall, extensive cellars and stores. Master bedroom with separate dressing room and ensuite bathroom, guest suite with dressing area and shower room, 7 further bedrooms and 3 further shower rooms. Swimming pool, Jacuzzi, pool room with changing rooms, bar and WCs, plant room, house boiler room, gardener’s WC, hobbies room and gym, stores, garaging for up to 4 cars, 3 stables and a tack room. Beautifully maintained gardens to the front and rear of the house extending to an immaculately kept former paddock edged with a conifer shelter belt. In all the property extends to approximately 4.05 acres (1.64 ha). Stamford office London office 9 High Street 17-18 Old Bond Street St. Martins London W1S 4PT Stamford PE9 2LF t 01780 484696 [email protected] SITUATION Alwalton lies to the west of the Cathedral city of Peterborough and to the east of the A1 dual carriageway, which is easily accessible. Th e village benefits from a Church, a public house serving food (Th e Cuckoo), a post office/village shop and a village hall.