Parry, LA, Vinther, J., & Edgecombe, GD (2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambrian Explosion: a Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals

The Cambrian Explosion A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Very suddenly, and at about the same horizon the world over, life showed up in the rocks with a bang. For most of Earth’s early history, there simply was no fossil record. Only recently have we come to discover otherwise: Life is virtually as old as the planet itself, and even the most ancient sedimentary rocks have yielded fossilized remains of primitive forms of life. NILES ELDREDGE, LIFE PULSE, EPISODES FROM THE STORY OF THE FOSSIL RECORD The Cambrian Explosion: A Big Bang in the Evolution of Animals Our home planet coalesced into a sphere about four-and-a-half-billion years ago, acquired water and carbon about four billion years ago, and less than a billion years later, according to microscopic fossils, organic cells began to show up in that inert matter. Single-celled life had begun. Single cells dominated life on the planet for billions of years before multicellular animals appeared. Fossils from 635,000 million years ago reveal fats that today are only produced by sponges. These biomarkers may be the earliest evidence of multi-cellular animals. Soon after we can see the shadowy impressions of more complex fans and jellies and things with no names that show that animal life was in an experimental phase (called the Ediacran period). Then suddenly, in the relatively short span of about twenty million years (given the usual pace of geologic time), life exploded in a radiation of abundance and diversity that contained the body plans of almost all the animals we know today. -

The Secrets of Fossils Lesson by Tucker Hirsch

The Secrets of Fossils Lesson by Tucker Hirsch Video Titles: Introduction: A New view of the Evolution of Animals Cambrian Explosion Jenny Clack, Paleontologist: The First Vertebrate Walks on Land Des Collins, Paleontologist: The Burgess Shale Activity Subject: Assessing evolutionary links NEXT GENERATION SCIENCE STANDARDS and evidence from comparative analysis of the fossil MS-LS4-1 Analyze and interpret data for patterns record and modern day organisms. in the fossil record that document the existence, diversity, extinction, and change of life forms Grade Level: 6 – 8 grades throughout the history of life on Earth under the Introduction assumptions that natural laws operate today as In this lesson students make connections between in the past. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis fossils and modern day organisms. Using the is on finding patterns of changes in the level of information about the Cambrian Explosion, they complexity of anatomical structures in organisms explore theories about how and why organisms diversified. Students hypothesize what evidence and the chronological order of fossil appearance might be helpful to connect fossil organisms to in the rock layers.] [Assessment Boundary: modern organisms to show evolutionary connections. Assessment does not include the names of Students use three videos from shapeoflife.org. individual species or geological eras in the fossil record.] Assessments Written MS-LS4-2 Apply scientific ideas to construct an Time 100-120 minutes (2 class periods) explanation for the anatomical similarities and Group Size Varies; single student, student pairs, differences among modern organisms and between entire class modern and fossil organisms to infer evolutionary relationships. [Clarification Statement: Emphasis Materials and Preparation is on explanations of the evolutionary relationships • Access to the Internet to watch 4 Shape of Life videos among organisms in terms of similarity or • Video Worksheet differences of the gross appearance of anatomical • “Ancient-Modern” Activity. -

The Fossil Record of the Cambrian “Explosion”: Resolving the Tree of Life Critics As Posing Challenges to Evolution

Article The Fossil Record of the Cambrian “Explosion”: 1 Resolving the Tree of Life Keith B. Miller Keith B. Miller The Cambrian “explosion” has been the focus of extensive scientifi c study, discussion, and debate for decades. It has also received considerable attention by evolution critics as posing challenges to evolution. In the last number of years, fossil discoveries from around the world, and particularly in China, have enabled the reconstruction of many of the deep branches within the invertebrate animal tree of life. Fossils representing “sister groups” and “stem groups” for living phyla have been recognized within the latest Precambrian (Neoproterozoic) and Cambrian. Important transitional steps between living phyla and their common ancestors are preserved. These include the rise of mollusks from their common ancestor with the annelids, the evolution of arthropods from lobopods and priapulid worms, the likely evolution of brachiopods from tommotiids, and the rise of chordates and echinoderms from early deuterostomes. With continued new discoveries, the early evolutionary record of the animal phyla is becoming ever better resolved. The tree of life as a model for the diversifi cation of life over time remains robust, and strongly supported by the Neoproterozoic and Cambrian fossil record. he most fundamental claim of bio- (such as snails, crabs, or sea urchins) as it logical evolution is that all living does to the fi rst appearance and diversi- T organisms represent the outer tips fi cation of dinosaurs, birds, or mammals. of a diversifying, upward- branching tree This early diversifi cation of invertebrates of life. The “Tree of Life” is an extreme- apparently occurred around the time of ly powerful metaphor that captures the the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary over essence of evolution. -

The Origin of Animal Body Plans: a View from Fossil Evidence and the Regulatory Genome Douglas H

© 2020. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2020) 147, dev182899. doi:10.1242/dev.182899 REVIEW The origin of animal body plans: a view from fossil evidence and the regulatory genome Douglas H. Erwin1,2,* ABSTRACT constraints on the interpretation of genomic and developmental The origins and the early evolution of multicellular animals required data. In this Review, I argue that genomic and developmental the exploitation of holozoan genomic regulatory elements and the studies suggest that the most plausible scenario for regulatory acquisition of new regulatory tools. Comparative studies of evolution is that highly conserved genes were initially associated metazoans and their relatives now allow reconstruction of the with cell-type specification and only later became co-opted (see evolution of the metazoan regulatory genome, but the deep Glossary, Box 1) for spatial patterning functions. conservation of many genes has led to varied hypotheses about Networks of regulatory interactions control gene expression and the morphology of early animals and the extent of developmental co- are essential for the formation and organization of cell types and option. In this Review, I assess the emerging view that the early patterning during animal development (Levine and Tjian, 2003) diversification of animals involved small organisms with diverse cell (Fig. 2). Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) (see Glossary, Box 1) types, but largely lacking complex developmental patterning, which determine cell fates by controlling spatial expression -

Ontogeny, Morphology and Taxonomy of the Softbodied Cambrian Mollusc

[Palaeontology, 2013, pp. 1–15] ONTOGENY, MORPHOLOGY AND TAXONOMY OF THE SOFT-BODIED CAMBRIAN ‘MOLLUSC’ WIWAXIA by MARTIN R. SMITH1,2,3 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G5, Canada 2Palaeobiology Section, Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 2C6, Canada 3Current address: Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EQ, UK; e-mail: [email protected] Typescript received 26 September 2012; accepted in revised form 25 May 2013 Abstract: The soft-bodied Cambrian organism Wiwaxia sclerites. I recognize a digestive tract and creeping foot in poses a taxonomic conundrum. Its imbricated dorsal scleri- Wiwaxia, solidifying its relationship with the contemporary tome suggests a relationship with the polychaete annelid Odontogriphus. Similarities between the scleritomes of worms, whereas its mouthparts and naked ventral surface Wiwaxia, halkieriids, Polyplacophora and Aplacophora hint invite comparison with the molluscan radula and foot. 476 that the taxa are related. A molluscan affinity is robustly new and existing specimens from the 505-Myr-old Burgess established, and Wiwaxia provides a good fossil proxy for Shale cast fresh light on Wiwaxia’s sclerites and scleritome. the ancestral aculiferan – and perhaps molluscan – body My observations illuminate the diversity within the genus plan. and demonstrate that Wiwaxia did not undergo discrete moult stages; rather, its scleritome developed gradually, with Key words: halwaxiids, scleritomorphs, Aculifera, Mollusca, piecewise addition and replacement of individually secreted evolution, Cambrian explosion. T HE slug-like Cambrian organism Wiwaxia perennially Nevertheless, Butterfield (2006, 2008) identified char- resists classification, in part due to its unusual scleritome acters that could place these taxa deeper within of originally chitinous scales and spines. -

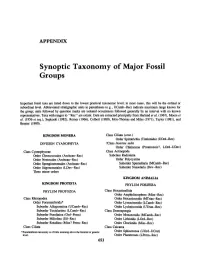

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Phylogeny of Hallucigenia

Phylogeny of Hallucigenia By Annette Hilton December 4th, 2014 Invertebrate Paleontology Cover artwork from: http://people.ds.cam.ac.uk/ms609/ 2 Abstract Hallucigenia is an extinct genus from the lower-middle Cambrian. A small worm-like organism with dorsal spines, Hallucigenia is rare in fossil history, and its identity and morphology have often been confounded. Since its original discovery in the Burgess Shale by Walcott, Hallucigenia has since become an iconic fossil. Its greater systematics and place in the phylogenetic tree is controversial and not completely understood. New evidence and the discovery of additional species of Hallucigenia have contributed much to the understanding of this genus and its broader relations in classification and evolutionary history. Introduction Hallucigenia is a genus that encompasses three known species that lived during the Cambrian period—Hallucigenia sparsa, Hallucigenia fortis, and Hallucigenia hongmeia (Ma et al., 2012). Hallucigenia’s taxonomy in figure 1. Kingdom Animalia Phylum Onychophora (Lobopodia) Class Xenusia Order Scleronychophora Genus Hallucigenia Figure 1. Taxonomy of Hallucigenia species. Collectively, all Hallucigenia specimens are rare, with a portion of specimens incomplete. The understanding of Hallucigenia and its life mode has been confounded since the 3 original discovery of H. sparsa, but subsequent species discoveries has shed light on some of its mysteries (Conway Morris, 1998). Even more information concerning Hallucigenia is currently being unearthed—its classification into the phylum Onychophora and wider relations to other invertebrate groups like Arthropoda and the poorly understood Lobopodian group (Campbell et al., 2011). Hallucigenia, an iconic fossil of the Burgess Shale, demonstrates the well-known diversity of the Cambrian period, its morphology providing increasing numbers of clues to its connection into the greater systematic system. -

Sepkoski, J.J. 1992. Compendium of Fossil Marine Animal Families

MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions . In BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 83 March 1,1992 A Compendium of Fossil Marine Animal Families 2nd edition J. John Sepkoski, Jr. MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions . In BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 83 March 1,1992 A Compendium of Fossil Marine Animal Families 2nd edition J. John Sepkoski, Jr. Department of the Geophysical Sciences University of Chicago Chicago, Illinois 60637 Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology Rodney Watkins, Editor (Reviewer for this paper was P.M. Sheehan) This publication is priced at $25.00 and may be obtained by writing to the Museum Gift Shop, Milwaukee Public Museum, 800 West Wells Street, Milwaukee, WI 53233. Orders must also include $3.00 for shipping and handling ($4.00 for foreign destinations) and must be accompanied by money order or check drawn on U.S. bank. Money orders or checks should be made payable to the Milwaukee Public Museum. Wisconsin residents please add 5% sales tax. In addition, a diskette in ASCII format (DOS) containing the data in this publication is priced at $25.00. Diskettes should be ordered from the Geology Section, Milwaukee Public Museum, 800 West Wells Street, Milwaukee, WI 53233. Specify 3Y. inch or 5Y. inch diskette size when ordering. Checks or money orders for diskettes should be made payable to "GeologySection, Milwaukee Public Museum," and fees for shipping and handling included as stated above. Profits support the research effort of the GeologySection. ISBN 0-89326-168-8 ©1992Milwaukee Public Museum Sponsored by Milwaukee County Contents Abstract ....... 1 Introduction.. ... 2 Stratigraphic codes. 8 The Compendium 14 Actinopoda. -

• Every Major Animal Phylum That Exists on Earth Today, As Well As A

• Every major animal phylum that exists on Earth today, as well as a few more that have since become ex:nct, appeared within less than 10 million years during the early Cambrian evolu:onary radiaon, also called the Cambrian explosion. Bristleworm • Phylum Annelida is represented by over 22,000 modern species of marine, freshwater, and terrestrial annelids, or segmented worms, including bristleworms, earthworms, and leeches. Earthworm These worms are classified separately from the roundworms in Phylum Nematoda and the flatworms in Phylum Platyhelminthes. Leech • The annelids may be further subdivided into Class Polychaeta, which includes the bristleworms (polychaetes), and Class Clitellata, which includes the earthworms (oligochaetes) and leeches (hirudineans). • The polychaetes, or bristleworms, are PlanKtonic Tomopteris the largest group of annelids and are mostly marine. They include species that live in the coldest ocean temperatures of the abyssal plain, to forms which tolerate the extreme high temperatures near hydrothermal vents. Polychaetes occur throughout the oceans at all depths, from planKtonic species such as Tomopteris that live near the surface to an unclassified benthonic form living at a depth of nearly 11,000 m at the boLom of the Challenger Deep in the Benthic sp. 1,200 m Mariana Trench. • Although many polychaetes are pelagic or benthic, others have adapted to burrowing, boring or tube-dwelling, and parasi:sm. • Each segment of a polychaete bears a pair of paddle-liKe and highly vascularized parapodia, which are used for locomo:on and, in many species, act as the worm’s primary respiratory surfaces. Bundles of chi:nous bristles, called chaetae, project from the parapodia. -

SKELETAL MICROSTRUCTURE INDICATES CHANCELLORIIDS and HALKIERIIDS ARE CLOSELY RELATED by SUSANNAH M

[Palaeontology, Vol. 51, Part 4, 2008, pp. 865–879] SKELETAL MICROSTRUCTURE INDICATES CHANCELLORIIDS AND HALKIERIIDS ARE CLOSELY RELATED by SUSANNAH M. PORTER Department of Earth Science, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; e-mail: [email protected] Typescript received 7 November 2005; accepted in revised form 7 September 2007 Abstract: Chancelloriids are problematic, sac-like animals and siphogonuchitid sclerites are homologous. The difference whose sclerites are common in Cambrian fossil assemblages. in chancelloriid and halkieriid body plans can be resolved in They look like sponges, but were united with the slug-like two ways. Chancelloriids either represent a derived condition halkieriids in the group Coeloscleritophora Bengtson and exhibiting complete loss of bilaterian characters or they repre- Missarzhevsky, 1981 based on a unique mode of sclerite con- sent the ancestral condition from which the bilaterally sym- struction. Because their body plans are so different, this pro- metric halkieriids, and the Bilateria as a whole, derived. The posal has never been well accepted, but detailed study of their latter interpretation, proposed by Bengtson (2005), implies sclerite microstructure presented here provides additional that coeloscleritophoran sclerites (‘coelosclerites’) are a plesi- support for this grouping. Both taxa possess walls composed omorphy of the Bilateria, lost or transformed in descendent of a thin, probably organic, sheet overlying a single layer of lineages. Given that mineralized coelosclerites appear in the aragonite fibres orientated parallel to the long axis of the fossil record no earlier than c. 542 Ma, this in turn implies sclerite. In all halkieriids and in the chancelloriid genus Archi- either that the Ediacaran record of bilaterians has been misin- asterella Sdzuy, 1969, bundles of these fibres form inclined terpreted or that coelosclerite preservability increased at the projections on the upper surface of the sclerite giving it a beginning of the Cambrian Period. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

THE BURGESS SHALE: A CAMBRIAN MIRROR FOR MODERN EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY by Keynyn Alexandra Ripley Brysse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Keynyn Alexandra Ripley Brysse (2008) Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44745-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44745-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Fossil Record and the Cambrian “Explosion”: an Update

THE FOSSIL RECORD AND THE CAMBRIAN “EXPLOSION”: AN UPDATE Keith B. Miller Department of Geology Kansas State University Saturday, July 20, 2013 Crown Groups, Stem Groups, and Sister Groups Saturday, July 20, 2013 Cambrian “Explosion” Timeline Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Doushantuo - 580 my Demosponges Presence of sponges extended to 700 my by biomarkers Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Hexactinellid Sponges Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Cnidaria (?) “Jellyfish-like” Organisms Mawsonites Nemaia 600 my Saturday, July 20, 2013 Neoproterozoic Cnidarian (Anthozoan) polyps and stalks Octocoral? Zoantharian? Saturday, July 20, 2013 Sinotubulites and Cloudinia Ediacaran Calcified Metazoans Namacalathus Sinocyclocyclicus Saturday, July 20, 2013 Early Cambrian Anemone-like Anthozoans Eolympia Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Algal Mats Wrinkled Microbial Mat Mat Ground with Vendian Fossils Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Bilaterian Spriggina Marywadea Saturday, July 20, 2013 Yorgia and Dickinsonia Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran Stem Mollusk Kimberella with grazing tracks Saturday, July 20, 2013 Ediacaran horizontal burrows Helminthopsis, Helminthoidichnites and Gordia Saturday, July 20, 2013 Below-mat Miners: Oldhamia Saturday, July 20, 2013 Trepichnus pedum basal Cambrian burrows Saturday, July 20, 2013 Cambrian Priapulid worms Saturday, July 20, 2013 Palaeoscolecid Worms Saturday, July 20, 2013 Stem Mollusks, Annelids Halkieria and Sister Taxa Canadia Wiwaxia Odontogriphus Orthozanclus Saturday, July 20, 2013 Mollusk Classes Helcionelloids