Downloads/CHECK Universitaetsleitung in Deutsc Hland.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Documents of Contemporary Art: TIME Edited by Amelia Groom, the Introduction Gives an Overview of Selected Writings Addressing Time in Relation to Art

“It is important to realize that the appointment that is in question in contemporariness does not simply take place in chronological time; it is something that, working within chronological time, urges, presses and transforms it. And this urgency is the untimeliness, the anachronism that permits us to grasp our time in the form of a ‘too soon’ that is also a ‘too late’; of an ‘already’ that is also a ‘not yet.’ Moreover, it allows us to recognize in the obscurity of the present the light that, without ever being able to reach us, is perpetually voyaging towards us.” - Giorgio Agamben 2009 What is the Contemporary? FORWARD ELAINE THAP Time is of the essence. Actions speak louder than words. The throughline of the following artists is that they all have an immediacy and desire to express and challenge the flaws of the Present. In 2008, all over the world were uprisings that questions government and Capitalist infrastructure. Milan Kohout attempted to sell nooses for homeowners and buyers in front of the Bank of America headquarters in Boston. Ernesto Pujol collaborated and socially choreographed artists in Tel Aviv protesting the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Indonesian artist, Arahmaiani toured the world to share “HIS Story,” performances creating problematic imagery ending to ultimately writing on her body to shine a spotlight on the effects of patriarchy and the submission of women. All of these artists confront terrorism from all parts of the world and choose live action to reproduce memory and healing. Social responsibility is to understand an action, account for the reaction, and to place oneself in the bigger picture. -

Wallmaps.Pdf

S Prenzlauer Allee U Volta Straße U Eberswalder Straße 1 S Greifswalder Straße U Bernauer Straße U Schwartzkopff Straße U Senefelderplatz S Nordbanhof Zinnowitzer U Straße U Rosenthaler Plaz U Rosa-Luxembury-Platz Berlin HBF DB Oranienburger U U Weinmeister Straße Tor S Oranienburger S Hauptbahnhof Straße S Alexander Platz Hackescher Markt U 2 S Alexander Plaz Friedrich Straße S U Schilling Straße U Friedrich Straße U Weberwiese U Kloster Straße S Unter den Linden Strausberger Platz U U Jannowitzbrucke U Franzosische Straße Frankfurter U Jannowitzbrucke S Tor 3 4 U Hausvogtei Platz U Markisches Museum Mohren Straße U U Spittelmarkt U Stadtmitte U Heirch-Heine-Straße S Ostbahnhof Potsdamer Platz S U Potsdamer Platz 5 S U Koch Straße Warschauer Straße Anhalter Bahnhof U SS Moritzplatz U Warschauer Mendelssohn- U Straße Bartholdy-Park U Kottbusser Schlesisches Tor U U Mockernbrucke U Gorlitzer U Prinzen Straße Tor U Gleisdreieck U Hallesches Tor Bahnhof U Mehringdamm 400 METRES Berlin wall - - - U Schonlein Straße Download five Eyewitnesses describe Stasi file and discover Maps and video podtours Guardian Berlin Wall what it was like to wake the plans had been films from iTunes to up to a divided city, with made for her life. Many 1. Bernauer Strasse Construction and escapes take with you to the the wall slicing through put their lives at risk city to use as audio- their lives, cutting them trying to oppose the 2. Brandenburg gate visual guides on your off from family and regime. Plus Guardian Life on both sides of the iPod or mp3 player. friends. -

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter Utgivna Av Statsvetenskapliga Föreningen I Uppsala 194

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194 Jessica Giandomenico Transformative Power Challenged EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Brusewitzsalen, Gamla Torget 6, Uppsala, Saturday, 19 December 2015 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor David Phinnemore. Abstract Giandomenico, J. 2015. Transformative Power Challenged. EU Membership Conditionality in the Western Balkans Revisited. Skrifter utgivna av Statsvetenskapliga föreningen i Uppsala 194. 237 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554-9403-2. The EU is assumed to have a strong top-down transformative power over the states applying for membership. But despite intensive research on the EU membership conditionality, the transformative power of the EU in itself has been left curiously understudied. This thesis seeks to change that, and suggests a model based on relational power to analyse and understand how the transformative power is seemingly weaker in the Western Balkans than in Central and Eastern Europe. This thesis shows that the transformative power of the EU is not static but changes over time, based on the relationship between the EU and the applicant states, rather than on power resources. This relationship is affected by a number of factors derived from both the EU itself and on factors in the applicant states. As the relationship changes over time, countries and even issues, the transformative power changes with it. The EU is caught in a path dependent like pattern, defined by both previous commitments and the built up foreign policy role as a normative power, and on the nature of the decision making procedures. -

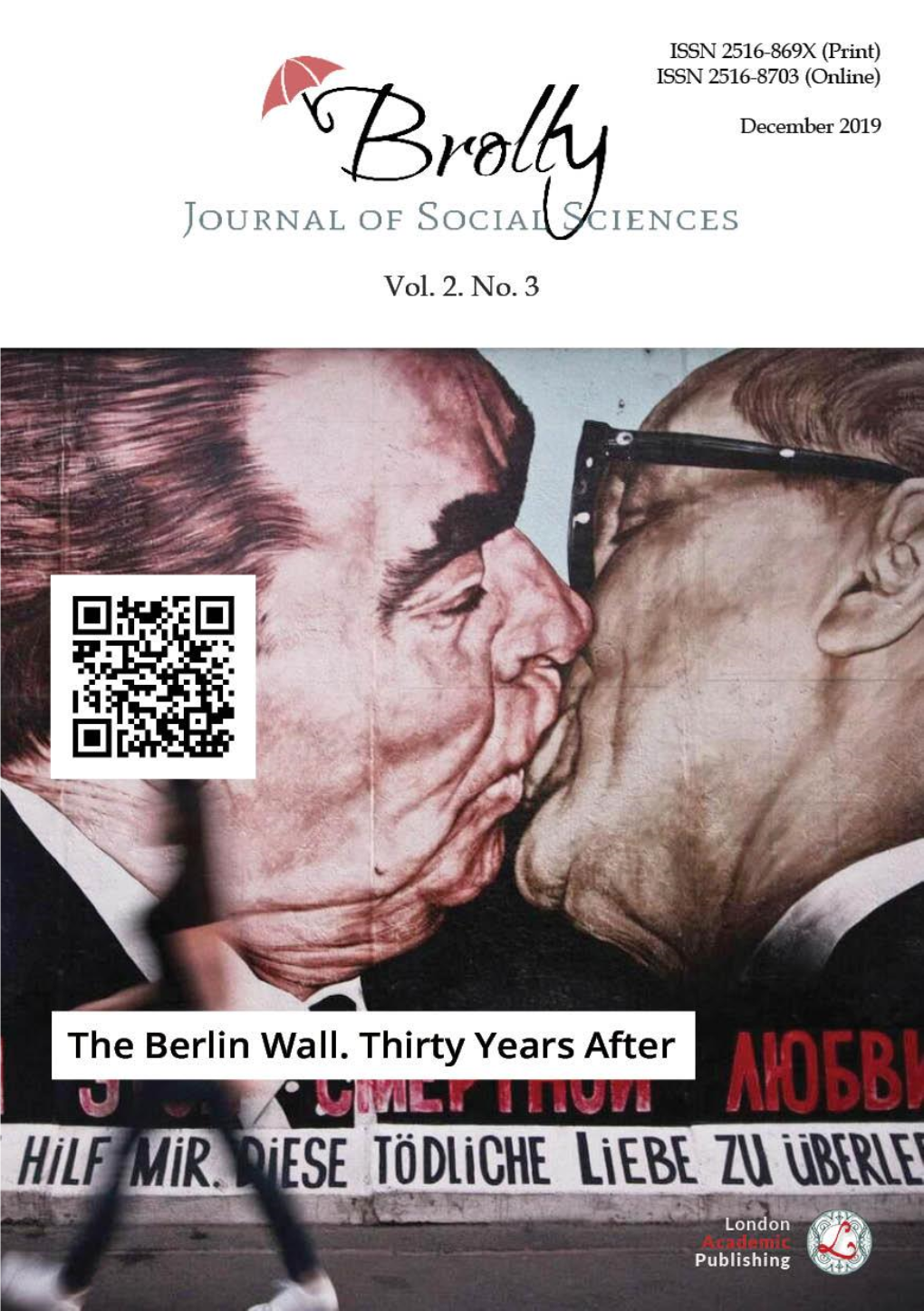

The Victims at the Berlin Wall, 1961-1989 by Hans-Hermann Hertle/Maria Nooke August 2011

Special CWIHP Research Report The Victims at the Berlin Wall, 1961-1989 By Hans-Hermann Hertle/Maria Nooke August 2011 Forty-four years after the Berlin Wall was built and 15 years after the East German archives were opened, reliable data on the number of people killed at the Wall were still lacking. Depending on the sources, purpose, and date of the studies, the figures varied between 78 (Central Registry of State Judicial Administrations in Salzgitter), 86 (Berlin Public Prosecution Service), 92 (Berlin Police President), 122 (Central Investigation Office for Government and Unification Criminality), and more than 200 deaths (Working Group 13 August). The names of many of the victims, their biographies and the circumstances in which they died were widely unknown.1 This special CWIHP report summarizes the findings of a research project by the Center for Research on Contemporary History Potsdam and the Berlin Wall Memorial Site and Documentation Center which sought to establish the number and identities of the individuals who died at the Berlin Wall between 1961 and 1989 and to document their lives and deaths through historical and biographical research.2 Definition In order to provide reliable figures, the project had to begin by developing clear criteria and a definition of what individuals are to be considered victims at the Berlin Wall. We regard the “provable causal and spatial connection of a death with an attempted escape or a direct or indirect cause or lack of action by the ‘border organs’ in the border territory” as the critical factor. In simpler terms: the criteria are either an attempted escape or a temporal and spatial link between the death and the border regime. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

The Beginning of the Berlin Wall Erin Honseler, Halie Mitchell, Max Schuetze, Callie Wheeler March 10, 2009

Group 8 Final Project 1 The Beginning of the Berlin Wall Erin Honseler, Halie Mitchell, Max Schuetze, Callie Wheeler March 10, 2009 For twenty-eight years an “iron curtain” divided East and West Berlin in the heart of Germany. Many events prior to the actual construction of the Wall caused East Germany’s leader Erich Honecker to demand the Wall be built. Once the Wall was built the cultural gap between East Germany and West Germany broadened. During the time the Wall stood many people attempted to cross the border illegally without much success. This caused a very unstable relationship between the government of the West (Federal Republic of Germany) and the government of the East (German Democratic Republic). In this paper we will discuss events leading up to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the government that was responsible for the construction of the Wall, how it divided Germany, and how some people tried to escape from the East to the West. Why the Berlin Wall Was Built In order to understand why the Berlin Wall was built, we must first look at the events leading up to the actual construction of the Wall in 1961. In the Aftermath of World War II Germany was split up into four different zones; each zone was controlled by a different country. The western half was split into three different sectors: the British sector, the American sector and the French sector. The Eastern half was controlled by the Soviet Union. Eventually, the three western occupiers unified their three zones and became what is known as the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

Chronik Band 4

Band IV Klaus Reinhold Chronik Arnstadt 704 - 2004 1300 Jahre Arnstadt 2. erweiterte und verbesserte Auflage Teil 4 (Fortsetzung) Hebamme Anna Kessel (Weiße 50) verhalf am 26.10.1942 dem viertausendstem Kind in ihrer langjährigen beruflichen Laufbahn zum Leben. 650 „ausgebombte“ Frauen und Kinder aus Düsseldorf trafen am 27.10.1942 mit einem Son- derzug in Arnstadt ein. Diamantene Hochzeit feierte am 28.10.1942 das Ehepaar Richard Zeitsch (86) und seine Ehefrau Hermine geb. Hendrich (81), Untergasse 2. In der Nacht vom Sonntag, dem 1. zum 2.11.1942, wurden die Uhren (um 3.00 Uhr auf 2.00 Uhr) um eine Stunde zurückgestellt. Damit war die Sommerzeit zu Ende und es galt wieder Normalzeit. Zum ersten Mal fand am 14.11.1942 in Arnstadt eine Hochzeit nach dem Tode statt. Die Näherin Silva Waltraud Gertrud Herzer heiratete ihren am 9.8.1941 gefallenen Verlobten, den Obergefreiten Artur Erich Hans Schubert mit dem sie ein Töchterchen namens Jutta (7 30.8.1939 in Arnstadt) hatte. Die Heirat erfolgte mit Wirkung des Tages vor dem Tode, also 8.8.1941. Die Tochter wurde „durch diese Eheschließung legitimiert“. 1943 Der Sturm 8143 des NS-Fliegerkorps baute Anfang 1943 auf dem Fluggelände Weinberg bei Arnstadt eine Segelflugzeughalle im Werte von 3500 RM. Die Stadt gewährte einen Zuschuß von 1000 RM und trat dem NS-Fliegerkorps als Fördermitglied mit einem Jahres- beitrag von 100,00 RM bei. Der fast 18-jährige Schüler Joachim Taubert (7 24.2.1925 in Arnstadt) wurde am 6.1.1943, 9.00 Uhr, in der Wohnung seiner Mutter, der Witwe Gertrud Elisabeth Taubert geb. -

Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan Mcmurry Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2018 Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan McMurry Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, Legal Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation McMurry, Keegan, "Schießbefehl and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials" (2018). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 264. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/264 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schießbefehl1 and the Issues of Retroactivity Within the East German Border Guard Trials Keegan J. McMurry History 499: Senior Seminar June 5, 2018 1 On February 5th, 1989, 20-year old Chris Gueffroy and his companion, Christian Gaudin, were running for their lives. Tired of the poor conditions in the German Democratic Republic and hoping to find better in West Germany, they intended to climb the Berlin Wall that separated East and West Berlin using a ladder. A newspaper account states that despite both verbal warnings and warning shots, both young men continued to try and climb the wall until the border guards opened fire directly at them. Mr. Gaudin survived the experience after being shot, however, Mr. -

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL FAMOUS EVENTS: What Happened

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL This week in Histor FAMOUS EVENTS: What happened on ... ? Was ist am 13. August 1961 geschehen? Building of the Berlin Wall Runners brave 160km marathon to mark fall of Berlin Wall "You have to accept that you will be moving for 24 hours," says west Berlin runner Nina Blisse, who finished both the 2014 and 2015 editions in under 26 hours and is race treasurer. The Wall's history is entwined in the race's DNA. Registration for the following year's race always opens at 18:57 (1657 GMT) on November 9 - marking the exact moment in 1989 when East Germany lifted its travel ban, triggering the Wall's demise. Each year, one Wall victim is chosen for a special tribute, their face featuring on start numbers and finisher medals, while a ceremony is held at the spot where they died. For the first race in 2011, Chris Gueffroy, the last person shot dead on the Berlin Wall, was honoured. He was killed in February 1989, eight months before the Wall fell, and on Sunday, Gueffroy's mother Karin will present medals at the finishers' ceremony. Political prisoners Last year, the Wall's youngest victim, Joerg Hartmann, a 10-year-old boy shot dead by East German border guards in 1966 while trying to visit his father in the west, was honoured. Having each been asked to carry a gift for him, last year's runners piled cuddly toys at the spot he was killed. "I still get goosebumps thinking about it," admits Ilk. For the organisers and 400 helpers, all volunteers, a sleepless night is par for the course. -

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-10

H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-10 Hope M. Harrison. After the Berlin War: Memory and the Making of the New Germany, 1989 to the Present. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019. ISBN: 9781107049314 (hardback, $34.99). 26 October 2020 | https://hdiplo.org/to/RT22-10 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse | Production Editor: George Fujii Contents Introduction by Charles Maier, Harvard University ............................................................................................................................. 2 Review by Pertti Ahonen, University of Jyvaskyla, Finland .............................................................................................................. 6 Review by Mark Fenemore, Manchester Metropolitan University ................................................................................................ 8 Review by Mary Fulbrook, University College London .................................................................................................................... 15 Review by William Glenn Gray, Purdue University ............................................................................................................................ 17 Review by Stephan Kieninger, Independent Historian ................................................................................................................... 20 Response by Hope M. Harrison, the George Washington University ......................................................................................... 23 H-Diplo Roundtable XXII-10 -

Bronx Princess

POV Community Engagement & Education Discussion GuiDe My Perestroika A Film by Robin Hessman www.pbs.org/pov PoV BLeatctkegrr foruonmd tinhefo friLmmamtaiokner Robin Hessman Photo courtesy of Red square Productions My Connection to Russia i have been curious about Russia and the soviet union for as long as i can remember. Growing up in the united states in the 1970s and early 1980s, it was impossible to miss the fact that the ussR was consid - ered our enemy and, according to movies and television, plotting to destroy the planet with its nuclear weapons. interest in the “evil empire” was everywhere. When i was seven, my second grade class made up a game: usA versus ussR. The girls were the united states, with headquarters at the jungle gym. The boys were the ussR, and were hunkered down at the sand box. And for some reason, the boys allowed me to be the only girl in the ussR. And thus, i was suddenly faced with a dilemma. My best friends were girls, but i was a curious kid, and i wanted to know what was going on in the ussR. un - able to choose between them, i became a double agent. i suppose it was my insatiable curiosity about this purportedly diabolical country that led me to beg my parents to allow me to subscribe to Soviet Life magazine at age ten. (i have no idea how i even knew it existed.) As children of the Mccarthy era in the 1950s, when thousands of Americans were accused of disloyalty and being communist sympathizers, my parents were concerned about the repercussions that the subscription to Soviet Life could have on my future.