Tamar Ron Marvin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires

Global Form and Fantasy in Yiddish Literary Culture: Visions from Mexico City and Buenos Aires by William Gertz Runyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mikhail Krutikov, Chair Professor Tomoko Masuzawa Professor Anita Norich Professor Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, University of Chicago William Gertz Runyan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3955-1574 © William Gertz Runyan 2019 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my dissertation committee members Tomoko Masuzawa, Anita Norich, Mauricio Tenorio and foremost Misha Krutikov. I also wish to thank: The Department of Comparative Literature, the Jean and Samuel Frankel Center for Judaic Studies and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for providing the frameworks and the resources to complete this research. The Social Science Research Council for the International Dissertation Research Fellowship that enabled my work in Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Tamara Gleason Freidberg for our readings and exchanges in Coyoacán and beyond. Margo and Susana Glantz for speaking with me about their father. Michael Pifer for the writing sessions and always illuminating observations. Jason Wagner for the vegetables and the conversations about Yiddish poetry. Carrie Wood for her expert note taking and friendship. Suphak Chawla, Amr Kamal, Başak Çandar, Chris Meade, Olga Greco, Shira Schwartz and Sara Garibova for providing a sense of community. Leyenkrayz regulars past and present for the lively readings over the years. This dissertation would not have come to fruition without the support of my family, not least my mother who assisted with formatting. -

Twenty Payment Life Policy the MASSACHUSETTS

II ADVERTISEMENTS A SAFE INVESTMENT FOR YOU Did you ever try to invest money safely? Experienced Financiers find this difficult: How much more so an inexperienced person. ...THE... Twenty Payment Life Policy (With its Combined Insurance and Endowment Features) ISSUED By THE MASSACHUSETTS MUTUAL LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY, OF SPRINGFIELD, MASS. is recommended to you as an investment, safe and profitable. The Policy is plain and simple and the privileges and values are stnted in plain figures that any one can read. It is a sure and systematic way of saving money for your own use or support in later years. Saving is largely a matter of habit. And the semi-compulsory feature cultivates that saving habit. Undir the contracts issued by the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insur- ance Company the protection afforded is unsurpassed. For further information address HOME OFFICE, Springfield, Mass., or New York Office, Empire Building, 71 Broadway. PHILADELPHIA OFFICE, - - - Philadelphia Bourse. BALTIMORE " 4 South Street. CINCINNATI " - Johnston Building. CHICAGO " Merchants Loan and Trust Building. ST. LOUIS " .... Century Building. ADVERTISEMENTS III 1851, 1901. The Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company, of Hartford, Connecticut, Issues Endowment Policies to either men or women, which (besides.giving Five other options) GUARANTEE when the Insured is Fifty, Sixty, or Seventy Years Old To Pay $1,500 in Cash for Every $1,000 of Insurance in force. Sample Policies, rates, and other information will be given on application to the Home Office. ¥ ¥ ¥ JONATHAN B. BUNCE, President. JOHN M. HOLCOMBE, Vice-President. CHARLES H. LAWRENCE, Secretary. MANAGERS: WEED & KENNEDY, New York. JULES GIRARDIN, Chicago. H. W. -

Columbus: Mystic, Zionist

1 COLUMBUS: MYSTIC, ZIONIST José Faur Netanya Academic College Columbus (died in Valladolid in May 20, 1506) is a man shrouded in mystery. On the one hand, he is the most important individual in modern history: single handedly he changed the face of the globe. On the other hand, little is known about his background and early life. There is a twofold reason for this mystery. First, Columbus and his contemporaries deliberately clouded highly signficant biographical data. Second, modern historians went out of their way to exclude key phrases used by Columbus and his contemporaries, and glossed over documentary evidence concerning crucial aspects of his biography and beliefs. What is commonly taught about him is neither consistent with, nor stands up to, critical investigation. The data offered by historians do not jive with the information given by Columbus about himself or with what his contemparies in Spain said. To avoid asking plain questions about the history and life of the great Discoverer, specialists perform all type of mental acrobatics. Both, the cryptic character of Columbus’ life and modern scholarship coincide in their efforts to becloud his biography; the motivation springs from a single source: prejudice. An investigation of the documentary evidence, particularly what Columbus wrote, shows that the great Discoverer came from a Jewish background. Américo Castro had shown that at the time of Columbus and throughout much of Spanish history, to acknowledge the Jewish background of anyone credited with a major contribution was anathema. Steeped in deep Mentalities/Mentalités Volume 28, Number 3, 2016 ISSN- 0111-8854 @2016 Mentalities/Mentalités All material in the Journal is subject to copyright; copyright is held by the journal except where otherwise indicated. -

Important Portuguese of the Past

Important Portuguese of the Past Vasco da Gama Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (Sines or Vidigueira, Alentejo, Portugal, around 1460 or 1469 – 24 December 1524 in Kochi, India) was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the European Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India. For a short time in 1524 he was Governor of Portuguese India under the title of Viceroy. Vasco da Gama's father was Estêvão da Gama. In the 1460s he was a knight in the household of the Duke of Viseu, Dom Fernando.[3] Dom Fernando appointed him Alcaide-Mór or Civil Governor of Sines and enabled him to receive a small revenue from taxes on soap making in Estremoz. Estêvão da Gama was married to Dona Isabel Sodré, who was the daughter of João Sodré (also known as João de Resende). Sodré, who was of English descent, had links to the household of Prince Diogo, Duke of Viseu, son of king Edward I of Portugal and governor of the military Order of Christ.[4] Little is known of Vasco da Gama's early life. It has been suggested by the Portuguese historian Teixeira de Aragão that he studied at the inland town of Évora, which is where he may have learned mathematics and navigation. It is evident that Gama knew astronomy well, and it is possible that he may have studied under the astronomer Abraham Zacuto.[5] In 1492 King John II of Portugal sent Gama to the port of Setúbal, south of Lisbon and to the Algarve to seize French ships in retaliation for peacetime depredations against Portuguese shipping - a task that Vasco rapidly and effectively performed. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

The Astronomical Navigation in Portugal in the Age of Discoveries

CAHIERS FRANÇOIS VIÈTE Série III – N° 3 201 7 History of Astronomy in Portugal Edited by Fernando B. Figueiredo & Colette Le Lay Centre François Viète Épistémologie, histoire des sciences et des techniques Université de Nantes - Université de Bretagne Occidentale Imprimerie Centrale de l'Université de Nantes Décembre 2017 Cahiers François Viète La revue du Centre François Viète Épistémologie, Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques EA 1161, Université de Nantes - Université de Bretagne Occidentale ISSN 1297-9112 [email protected] www.cfv.univ-nantes.fr Depuis 1999, les Cahiers François Viète publient des articles originaux, en français ou en anglais, d'épistémologie et d'histoire des sciences et des techniques. Les Cahiers François Viète se sont dotés d'un comité de lecture international depuis 2016. Rédaction Rédactrice en chef – Jenny Boucard Secrétaire de rédaction – Sylvie Guionnet Comité de rédaction – Delphine Acolat, Frédéric Le Blay, Colette Le Lay, Karine Lejeune, Cristiana Oghina-Pavie, David Plouviez, Pierre Savaton, Pierre Teissier, Scott Walter Comité de lecture Martine Acerra, Yaovi Akakpo, Guy Boistel, Olivier Bruneau, Hugues Chabot, Ronei Clecio Mocellin, Jean-Claude Dupont, Luiz Henrique Dutra, Fernando Figueiredo, Catherine Goldstein, Jean-Marie Guillouët, Céline Lafontaine, Pierre Lamard, Philippe Nabonnand, Karen Parshall, François Pepin, Olivier Perru, Viviane Quirke, Pedro Raposo, Anne Rasmussen, Sabine Rommevaux- Tani, Martina Schiavon, Josep Simon, Rogerio Monteiro de Siqueira, Ezio Vaccari, -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

Chinese Porcelain Ordered by Portuguese Jews in the Diaspora*

Chinese Porcelain Ordered by Portuguese Jews 473 Chapter 21 Chinese Porcelain Ordered by Portuguese Jews in the Diaspora* Roberto Bachmann For a better understanding of the subject referred to in the title, we have to look into the historical background of the Jews in Portugal and the Jewish fam- ilies that originated from there. The Jews in Portugal around the year 1500 were a minority, numbering between 80,000 and 100,000 in a population of about one million inhabitants. This number included about 40,000 Portuguese Jews and about 50,000 Jews exiled from Spain after 1391, but mainly after August 1492, the date when their expulsion was implemented by Isabel and Fernando, the “Catholic Kings,” rep- resenting around ten per cent of the total population of Portugal at the end of the fifteenth century. This Jewish minority lived in harmony with the local powers, and was to a large degree tolerated under the protection of the kings of Portugal, whom they served in the fiscal administration, in the economy and in the sciences. They contributed from the beginning with their scientific knowledge to the Portuguese discoveries, with leading figures such as Rabbi Abraham Zacuto, mathematician to the King and author of the Perpetual Almanac, his disciple, Master José Vizinho, physician and astrologer to King João II. A probable great- great grandson of Zacuto, by the name of Manuel Álvares de Távora, called Zacuto Lusitano, was a doctor of great prestige, who left an important collec- tion of writings. However, the break came in 1496 when the Edict of Expulsion of the Jews from Portuguese territory was signed in Muge (Ribatejo) by King Manuel I, supposedly for dynastic reasons, followed a year later by the decree of forced conversion of the entire Jewish population, now transmuted into “conversos,” in Portugal called New Christians, and then in 1499 when their emigration from the country was forbidden, whether as individuals or in groups. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

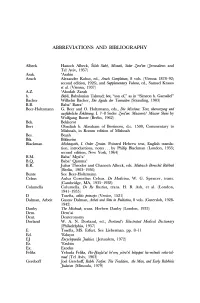

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour.