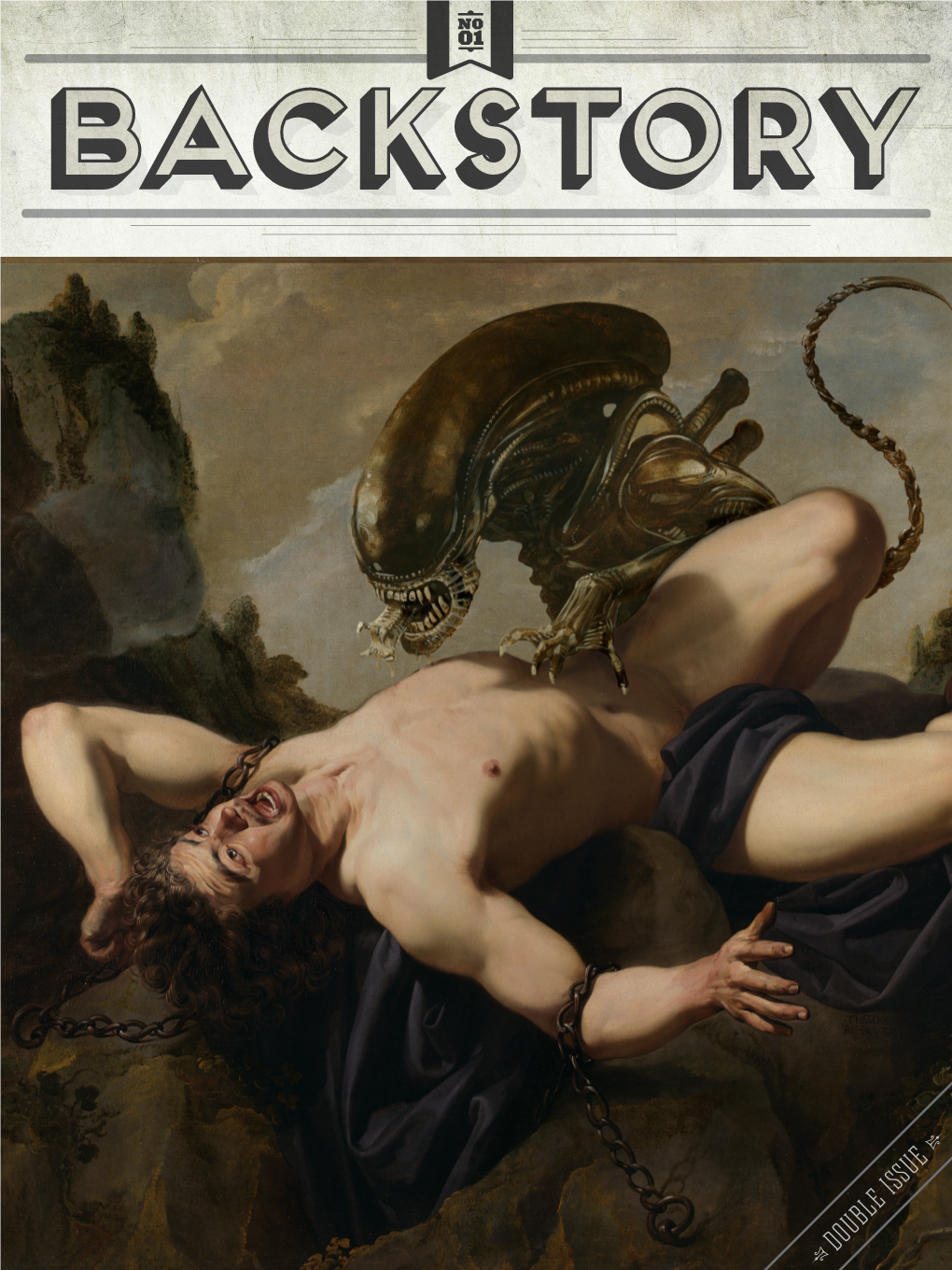

DOUBLE ISSUE ! (Touch Each Picture to Read the Story)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Pl

SAG/AFTRA FILM (Partial List) Scare Package Supporting/ “Officer Ragen” Paper Street Pictures/ Aaron B. Koontz Dir. Human Play Lead/ “James” Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Little Woods Supporting/ "Man" Buffalo Picture House/ Nia DaCosta Dir. Elephone Man Lead/ "Bobby" Global Films/ Magarditch Halvadjian Dir. The Cable Men Starring/ "Barney" McShane Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Bitch (Short) Supporting/ "Will" Edgen Films/ Robin Conly Dir. Small Packages (Short) Starring/ "Porter" Grade A Films/ Anthony Faust Dir. An American In Texas Lead/ "Earl Doonan" Film Exchange/ Anthony Pedone Dir. Overcast (Short) Lead/ "Paulie" Atomic Productions/ Ben Adams Dir. Bomb City Supporting/ "Officer Chuck" 3rd Identity Films/ Jamie Brooks Dir. As Far As The Eye Can See Supporting/ "Bob Tanner" AFATECS LLC/ David Franklin Dir. Entity Starring/ "Eugene" Screengage LLC/ Michael Yurinko Dir. Human Play Lead/ "James" Paper Street Pictures/ Mathieu Ricordi Dir. Hard Reset 3-D Lead/ "Det. Wright" Buk Films/ Deepak Chetty Dir. The Doo Dah Man Supporting/ "Frank" Flatiron Pictures/ Claude Green Dir. Adventures of Pepper and Paula Lead/ "Ricky" The Nations/ Kevin & Robin Nations Dir. Sin City 2 Supporting/ "Tourist" Troublemaker/ Robert Rodriguez Dir. TELEVISION The Pact (Mini Series) Lead/ ”Drummer” Katara Studios/ Michael Phillips EP. Three Knee Deep (Mini Series) Lead/ "Jack" Luna/Luca Bercovichi Dir. The Leftovers Recurring/ "Sam" HBO/ Damon Lindelof EP. Queen of the South Co-Star/ "Donald Henry" USA/ Matthew Penn EP. From Dusk Til Dawn Co-Star/ "Chester" El Rey/ Eduardo Sanchez Dir. In An Instant Starring/ "Pete Soulis" ABC/ Todd Cobery Dir. American Crime Co-Star/ "Patrol Officer" ABC/ John Ridley Dir. -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

2012 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contacts: January 28, 2012 Casey De La Rosa 310.360.1981 [email protected] 2012 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES AWARDS The House I Live In, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Law in These Parts and Violeta Went to Heaven Earn Grand Jury Prizes Audience Favorites Include The Invisible War, The Surrogate, SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN and Valley of Saints Sleepwalk With Me Receives Best of NEXT <=> Audience Award Park City, UT — Sundance Institute this evening announced the Jury, Audience, NEXT <=> and other special awards of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival at the Festival‘s Awards Ceremony, hosted by Parker Posey in Park City, Utah. An archived video of the ceremony in its entirety is available at www.sundance.org/live. ―Every year the Sundance Film Festival brings to light exciting new directions and fresh voices in independent film, and this year is no different,‖ said John Cooper, Director of the Sundance Film Festival. ―While these awards further distinguish those that have had the most impact on audiences and our jury, the level of talent showcased across the board at the Festival was really impressive, and all are to be congratulated and thanked for sharing their work with us.‖ Keri Putnam, Executive Director of Sundance Institute, said, ―As we close what was a remarkable 10 days of the 2012 Sundance Film Festival, we look to the year ahead with incredible optimism for the independent film community. As filmmakers continue to push each other to achieve new heights in storytelling we are excited to see what‘s next.‖ The 2012 Sundance Film Festival Awards presented this evening were: The Grand Jury Prize: Documentary was presented by Charles Ferguson to: The House I Live In / U.S.A. -

The Black List New Zealand Project Guidelines for Applicants

Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga New Zealand Film Commission in partnership with The Black List New Zealand Project Script Development Workshop with the Black List and NZFC Development Financing Guidelines for Applicants January 2021 You are encouraged to read these guidelines carefully as they are intended to help you deliver the strongest application possible. Please also read the relevant information sheets on the NZFC website (Development Grant Agreement Information Sheet and New Zealand Content Information Sheet) Please feel free to get in touch before making an application, as we can offer helpful advice and guidance – [email protected] The New Zealand Film Commission Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga (NZFC) is committed to ensuring New Zealand has a successful screen industry. We are here to help people in the industry make films that are high impact, authentic and culturally significant. We want to support a diverse range of narrative feature films that will attract audiences here and overseas and further the careers of the filmmakers and the production companies behind them. The NZFC has partnered with the Black List™ to introduce the Black List New Zealand Project (BLNZP). This is a one-off fund, designed to foster the creative relationship between writers and producers and stimulate international opportunities for New Zealand feature films. Additionally, the NZFC hopes to cast a wide net for screenwriting talent and connect with projects at various stages of development. BLNZP will support the development of six quality, unique and exciting feature film scripts, with the potential of attracting the US and global market. The Black List will review all scripts submitted to the BLNZP and compile a shortlist of 20 scripts based on the assessment criteria outlined in these guidelines. -

Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic

SOFIA COPPOLA AND THE SIGNIFICANCE OF AN APPEALING AESTHETIC by LEILA OZERAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Leila Ozeran for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2016 Title: Sofia Coppola and the Significance of an Appealing Aesthetic Approved: r--~ ~ Professor Priscilla Pena Ovalle This thesis grew out of an interest in the films of female directors, producers, and writers and the substantially lower opportunities for such filmmakers in Hollywood and Independent film. The particular look and atmosphere which Sofia Coppola is able to compose in her five films is a point of interest and a viable course of study. This project uses her fifth and latest film, Bling Ring (2013), to showcase Coppola's merits as a filmmaker at the intersection of box office and critical appeal. I first describe the current filmmaking landscape in terms of gender. Using studies by Dr. Martha Lauzen from San Diego State University and the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media to illustrate the statistical lack of a female presence in creative film roles and also why it is important to have women represented in above-the-line positions. Then I used close readings of Bling Ring to analyze formal aspects of Sofia Coppola's filmmaking style namely her use of distinct color palettes, provocative soundtracks, car shots, and tableaus. Third and lastly I went on to describe the sociocultural aspects of Coppola's interpretation of the "Sling Ring." The way the film explores the relationships between characters, portrays parents as absent or misguided, and through film form shows the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Sofia Coppola has given Bling Ring has a central ii message, substance, and meaning: glamorous contemporary celebrity culture can have dangerous consequences on unchecked youth. -

May 1 9 1Qqa

CRIMINAL BRANCH (213) 485-5452 CIVIL BRANCH (213) 485-6370 of tke Tag cAttermg ffire WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL (213)485-5403 7El:1e cAngrle, alifurttia NUMBER JAMES K. HAHN CITY ATTORNEY 09 0 7 5 REPORT NO. MAY 1 9 1QQA REPORT RE POSSIBLE REVISIONS TO THE CITY'S LIVING WAGE ORDINANCE CONCERNING THE COVERAGE OF CITY TENANTS The Honorable City Council City of Los Angeles Room 607, City Hall 200 N. Main Street Los Angeles, CA 90012 [Council File 96-1111-S1 not transmitted but referred to] Honorable Members: THE COVERAGE OF CITY TENANTS UNDER THE LIVING WAGE ORDINANCE. The City's Living Wage Ordinance ("LWO"), Los Angeles Administrative Code §§ 10.37 et seq:, has beep)op,erative since May 5, 1997. While a number of questions have arisen about the interpretation or application of this legislation in the past year, perhaps of greatest interest recently have been questions raised concerning the extent to which activities of City tenants have been and should be covered. In § 10.37.1(h) the LWO defines "service contract" so as to cover those leases and licenses issued by City departments under which "services are rendered for the City" where it has been determined that "but for" such lease or license the "services to be rendered probably would otherwise be rendered by City employees." The meaning of this ordinance AN EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY - AFFIRMATIVE ACTION EMPLOYER EIGHTEENTH FLOOR, CITY HALL EAST • 200 N. MAIN STREET • LOS ANGELES CA 90012-4131 Recyclable and made from recycled waste TeK:9 The City Council City of Los Angeles Page 2 language has been center stage most prominently in connection with disputes over whether the LWO should apply to certain airline leases let by the Department of Airports.' The purpose of this report is to offer the Mayor and City Council an opportunity to clarify and possibly modify the LWO in regard to City tenants. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY of ENGLISH USE in COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROWS MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 PARASITIC MIRATIVITY OF ENGLISH USE IN COLIN TREVORROW’S MOVIE “JURASSIC WORLD” Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Humaniora in English and Literature Department of Faculty of Adab and Humanities of UIN Alauddin Makassar By MUJI RETNO Reg. No. 40300111080 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2016 i MOTTO “EDUCATION IS WHAT REMAINS AFTER ONE HAS FORGOTTEN WHAT ONE HAS LEARNED IN SCHOOL.” (Albert Eistein) “EDUCATION IS A PROGRESSIVE DISCOVERY OF OUR OWN IGNORENCE.” (Charlie Chaplin) “EVERY THE LAST STEP INEVITABLY HAS THE FIRST STEP” (Muji Retno) ii ACKNOWLEDGE All praises to Allah who has blessed, guided and given the health to the researcherduring writing this thesis. Then, the researcherr would like to send invocation and peace to Prophet Muhammad SAW peace be upon him, who has guided the people from the bad condition to the better life. The researcher realizes that in writing and finishing this thesis, there are many people that have provided their suggestion, advice, help and motivation. Therefore, the researcher would like to express thanks and highest appreciation to all of them. For the first, the researcher gives special gratitude to her parents, Masir Hadis and Jumariah Yaha who have given their loves, cares, supports and prayers in every single time. -

Cistercian Preparatory School: the First 50 Year

CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS 1962 2012 David E. Stewart Headmasters CISTercIAN PreparaTORY SCHOOL 1962 - 2012 Fr. Damian Szödényi, 1962 - 1969 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1969 - 1974 Fr. Henry Marton 1974 - 1975 Fr. Denis Farkasfalvy, 1975 - 1981 Fr. Bernard Marton, 1981 - 1996 Fr. Peter Verhalen ’73, 1996 - 2012 Fr. Paul McCormick, 2012 - Fr. Damian Szödényi Fr. Henry Marton Headmaster, 1962 - 1969 Headmaster, 1974 - 1975 (b. 1912, d. 1998) (b. 1925, d. 2006) Pictured on the cover (l-r): Fr. Bernard Marton, Abbot Peter Verhalen ’73, Fr. Paul McCormick, and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy. Cover photo by Jim Reisch CISTERCIAN PREPARATORY SCHOOL THE FIRST 50 YEARS David E. Stewart ’74 Thanks and acknowledgements The heart of this book comes from over ten years of stories published in The Continuum, the alumni magazine for Cistercian Prep School. Thanks to Abbot Peter Verhalen and Abbot Emeritus Denis Farkasfalvy and many other monks, faculty members, staff, alumni, and parents for their trust and willingness to share so much in the pages of the magazine and this book. Christine Medaille contributed her time and talent to writing Chapter 8 and Brian Melton ’71 contributed mightily to Chapter 11. Thanks to Jim Reisch for his outstanding photography throughout this book, and especially for the cover shot. Priceless moments from the sixties were captured by or provided by Jane Bret and Fr. Melchior Chladek. Thanks to Rodney Walter for collecting the yearbook photographs used in the book and identifying the students in them. Thanks to Fr. Bernard Marton, Sylvia Najera, and Bridgette Gimenez for their help in editing and proofing.