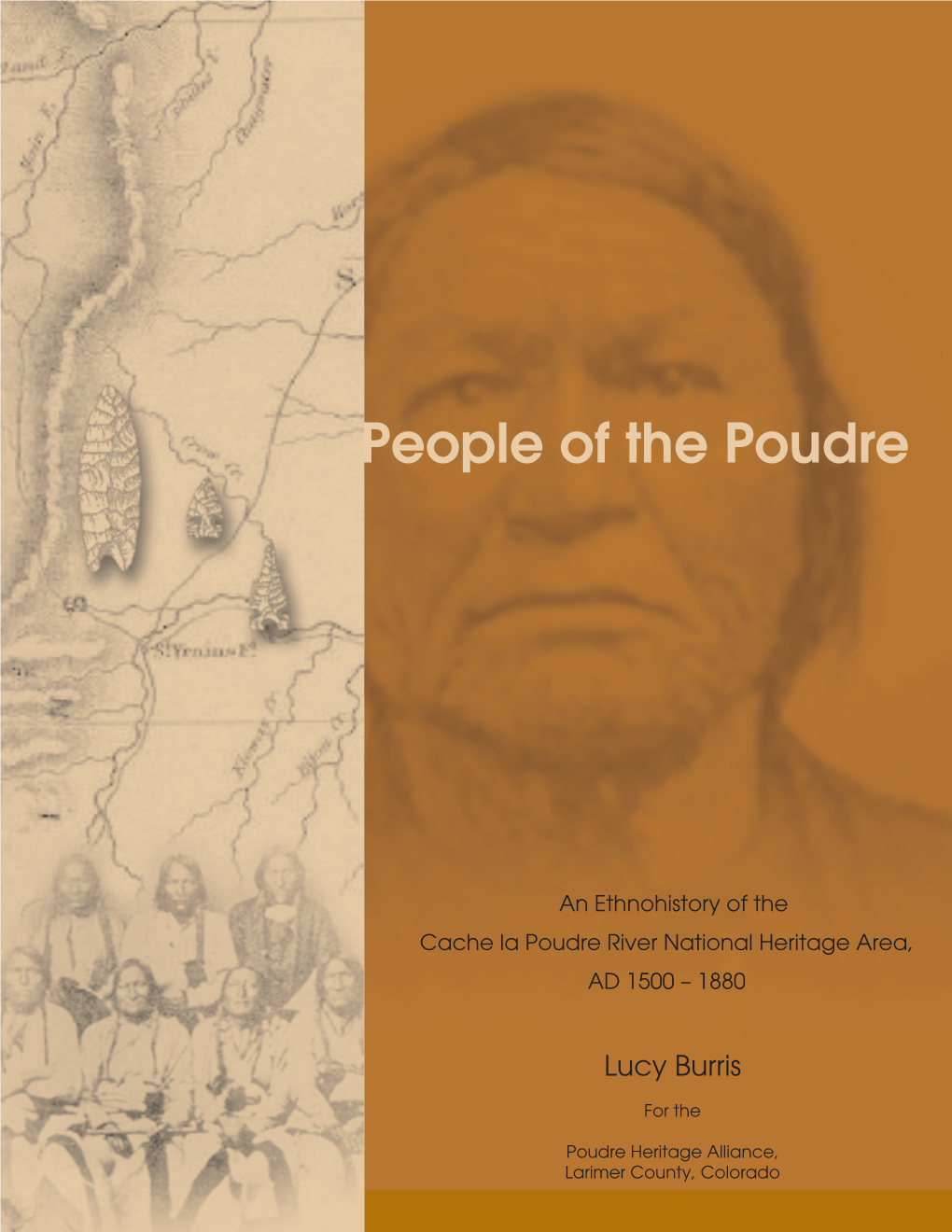

People of the Poudre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado History Chronology

Colorado History Chronology 13,000 B.C. Big game hunters may have occupied area later known as Colorado. Evidence shows that they were here by at least 9200 B.C. A.D. 1 to 1299 A.D. Advent of great Prehistoric Cliff Dwelling Civilization in the Mesa Verde region. 1276 to 1299 A.D. A great drought and/or pressure from nomadic tribes forced the Cliff Dwellers to abandon their Mesa Verde homes. 1500 A.D. Ute Indians inhabit mountain areas of southern Rocky Mountains making these Native Americans the oldest continuous residents of Colorado. 1541 A.D. Coronado, famed Spanish explorer, may have crossed the southeastern corner of present Colorado on his return march to Mexico after vain hunt for the golden Seven Cities of Cibola. 1682 A.D. Explorer La Salle appropriates for France all of the area now known as Colorado east of the Rocky Mountains. 1765 A.D. Juan Maria Rivera leads Spanish expedition into San Juan and Sangre de Cristo Mountains in search of gold and silver. 1776 A.D. Friars Escalante and Dominguez seeking route from Santa Fe to California missions, traverse what is now western Colorado as far north as the White River in Rio Blanco County. 1803 A.D. Through the Louisiana Purchase, signed by President Thomas Jefferson, the United States acquires a vast area which included what is now most of eastern Colorado. While the United States lays claim to this vast territory, Native Americans have resided here for hundreds of years. 1806 A.D. Lieutenant Zebulon M. Pike and small party of U.S. -

Indian Trust Asset Appendix

Platte River Endangered Species Recovery Program Indian Trust Asset Appendix to the Platte River Final Environmental Impact Statement January 31,2006 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Denver, Colorado TABLE of CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 The Recovery Program and FEIS ........................................................................................ 1 Indian trust Assets ............................................................................................................... 1 Study Area ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Indicators ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Background and History .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview - Treaties, Indian Claims Commission and Federal Indian Policies .................. 5 History that Led to the Need for, and Development of Treaties ....................................... -

Includes Tribal Court Decision

4:07-cv-03101-RGK-CRZ Doc # 82 Filed: 02/14/13 Page 1 of 3 - Page ID # 598 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEBRASKA THE VILLAGE OF PENDER, NEBRASKA, ) Case No. 4:07-cv-03101 RICHARD M. SMITH, DONNA SMITH, ) DOUG SCHRIEBER, SUSAN SCHRIEBER, ) RODNEY A. HEISE, THOMAS J. WELSH, ) JAY LAKE, JULIE LAKE, KEITH ) BREHMER, and RON BRINKMAN, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) JOINT STATUS REPORT AND MOTION ) FOR STATUS CONFERENCE MITCHELL PARKER, In his official ) WITH DISTRICT JUDGE capacity as Member of the Omaha Tribal ) Council, BARRY WEBSTER, In his official ) capacity as Vice-Chairman of the Omaha ) Tribal Council, AMEN SHERIDAN, In his ) official capacity as Treasurer of the Omaha ) Tribal Council, RODNEY MORRIS, In his ) official capacity as Secretary of the Omaha ) Tribal Council, TIM GRANT, In his official ) capacity as Member of the Omaha Tribal ) Council, STERLING WALKER, In his ) official capacity as Member of the Omaha ) Tribal Council, and ANSLEY GRIFFIN, In ) his official capacity as Chairman of the ) Omaha Tribal Council and as the Omaha ) Tribe’s Director of Liquor Control. ) ) Defendants. ) Plaintiffs and Defendants file this Joint Status Report pursuant to the court’s Memorandum and Order dated October 4, 2007. 1. Cross motions for summary judgment were heard by the Omaha Tribal Court on September 10, 2012. 2. On February 4, 2013, the Omaha Tribal Court issued a “Memorandum Opinion and Order,” ruling in favor of Defendants, on the parties’ cross motions for summary judgment. See Ex. 1. 4:07-cv-03101-RGK-CRZ Doc # 82 Filed: 02/14/13 Page 2 of 3 - Page ID # 599 3. -

Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany

Kindscher, L. Yellow Bird, M. Yellow Bird & Sutton Yellow M. Bird, Yellow L. Kindscher, Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany This book describes the traditional use of wild plants among the Arikara (Sahnish) for food, medicine, craft, and other uses. The Arikara grew corn, hunted and foraged, and traded with other tribes in the northern Great Plains. Their villages were located along the Sahnish (Arikara) Missouri River in northern South Dakota and North Dakota. Today, many of them live at Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, as part of the MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) Ethnobotany Nation. We document the use of 106 species from 31 plant families, based primarily on the work of Melvin Gilmore, who recorded Arikara ethnobotany from 1916 to 1935. Gilmore interviewed elders for their stories and accounts of traditional plant use, collected material goods, and wrote a draft manuscript, but was not able to complete it due to debilitating illness. Fortunately, his field notes, manuscripts, and papers were archived and form the core of the present volume. Gilmore’s detailed description is augmented here with historical accounts of the Arikara gleaned from the journals of Great Plains explorers—Lewis and Clark, John Bradbury, Pierre Tabeau, and others. Additional plant uses and nomenclature is based on the field notes of linguist Douglas R. Parks, who carried out detailed documentation of the Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany tribe’s language from 1970–2001. Although based on these historical sources, the present volume features updated modern botanical nomenclature, contemporary spelling and interpretation of Arikara plant names, and color photographs and range maps of each species. -

Chapter 3 Arapaho Ethnohistory and Historical

Chapter 3 Arapaho Ethnohistory and Historical Ethnography ______________________________________________________ 3.1 Introduction The Arapaho believe they were the first people created on earth. The Arapaho called themselves, the Hinanae'inan, "Our Own Kind of People.”1 After their creation, Arapaho tradition places them at the earth's center. The belief in the centrality of their location is no accident. Sociologically, the Arapaho occupied the geographical center among the five ethnic distinct tribal-nations that existed prior to the direct European contact.2 3.2 Culture History and Territory Similar to many other societies, the ethnic formation of the Arapaho on the Great Plains into a tribal-nation was a complex sociological process. The original homeland for the tribe, according to evidence, was the region of the Red River and the Saskatchewan River in settled horticultural communities. From this original homeland various Arapaho divisions gradually migrated southwest, adapting to living on the Great Plains.3 One of the sacred objects, symbolic of their life as horticulturalists, that they carried with them onto the Northern Plains is a stone resembling an ear of corn. According to their oral traditions, the Arapaho were composed originally of five distinct tribes. 4 Arapaho elders remember the Black Hills country, and claim that they once owned that region, before moving south and west into the heart of the Great Plains. By the early nineteenth century, the Arapaho positioned themselves geographically from the two forks of the Cheyenne River, west of the Black Hills southward to the eastern front 87 of the central Rocky Mountains at the headwaters of the Arkansas River.5 By 1806 the Arapaho formed an alliance with the Cheyenne to resist against further intrusion west by the Sioux beyond the Missouri River. -

Merciad Writer "Hangs Out" with Yamato Page 8 Hurst Soccer I

THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF MERCYHURST COLLEGE SINCE 1929 ARTS& Hurst ENTERTAINMENT soccer I Merciad writer teams head "hangs out" with to playoffs Yamato page 8 page 12 Vol 75 No. 7 Mercyhurst College 501 E. 38th St. Erie, Pa. 16546 November 8; 2001 Anthrax threat turns out to be hoax By Annie DeMeo Staff writer The "Mercyworld" bubble was de- cidedly popped Tuesday. Oct. 30 when a Mercyhurst employee opened an envelope postmarked Cairo, Egypt containing a suspicious white pow- der. * The Federal Bureau of Investiga- tion notified the college at about 2 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 2 with test re- sults revealing that the powder was not anthrax. Despite the fact that the letter was a hoax, it was successful in upsetting the routine of the college. Thirty seven individuals that c a m e in closest contact with the letter were quarantined immediately. F ™ t* About 500 students, faculty, staff; and administrators that were believed to be at risk of exposure were in- structed to undergo testing and, in most cases, prescribed to take the an- Annie Sitter/Merciad photographer tibiotic Cipro as a preventative mea- Effects of the national crisis touched Mercyhurst College Tuesday October 31 after a letter, threatening that it contained anthrax, was sure. * received in the admissions office. The letter, postmarked Cairo* Egypt, was later determined to be a hoax, testing negative for anthrax. Classes in Old Main were cancelled for both Wednesday and Thursday, 'The staff acted very quickly as blocked off. ing they were wearing as well as any dents through both the Cohen Student further disrupting the campus. -

On Our Drive Back Through Utah from Rocky Mountain National Park, We Had a Couple of Hours to Stop at the Dinosaur National Monu

DINOSAUR NATIONAL MONUMENT: QUARRY EXHIBIT HALL, SPLIT MOUNTAIN VIEWPOINT, AND SWELTER SHELTER ! PETROGLYPHS AND PICTOGRAPHS On our drive back through Utah from Rocky Mountain National Park, we had a couple of hours to stop at the Dinosaur National Monument after driving out of RMNP through the Trail Ridge Road. Best known for the huge wall of dinosaur fossils, protected by a large and enclosed building, which visitors can see by taking a shuttle bus from the main visitors center, this national monument also has a surprising collection of amazing rock formations. Unfortunately, we did not have time to see much of the monument, but there are many paved, dirt, and 4WD access roads to overlooks of the Green and Yampa Rivers, petroglyphs and pictographs, slot canyons, and historical cabins. After visiting the Quarry Exhibit Hall, we briefly checked out the Fossil Discovery Trail, then continued on to an overlook of Split Mountain and the Green River. We had considered continuing along this road to see more overlooks on the way to the Josie Morris Cabin, but we didn't have enough time, and therefore only were able to stop at the Swelter Shelter petroglyphs and !pictographs. The views from Trail Ridge Road on our drive out of Rocky Mountain National Park were a little different on such a clear day; this is Sundance Mountain pictured below: ! ! There was still quite a bit of snow on the peaks, making for good photography again: ! ! Looking over towards the Gorge Lakes (in the valley to the left, with Arrowhead Lake visibly iced over and Highest -

2018NABI Teams.Pdf

TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE TEAM NAME COACH TRIBE STATE 1 ALASKA (D1) S. Craft Unalakleet, Akiachak, Akiak, Qipnag, Savoonga, Iqurmiut AK 33 THREE NATIONS (D1) G. Tashquinth Tohono O'odham, Navajo, Gila River AZ 2 APACHE OUTKAST (D1) J. Andreas White Mountain Apache AZ 34 TRIBAL BOYZ (D1) A. Strom Colville, Mekah, Nez Perce, Quinault, Umatilla, Yakama WA 3 APACHES (D1) T. Antonio San Carlos Apache AZ 35 U-NATION (D1) J. Miller Omaha Tribe of Nebraska NE 4 AZ WARRIORS (D1) R. Johnston Hopi, Dine, Onk Akimel O'odham, Tohono O'odham AZ 36 YAQUI WARRIORS (D1) N. Gorosave Pascua Yaqui AZ Pima, Tohono O'odham, Navajo, White Mountain Apache, 5 BADNATIONZ (D1) K. Miller Sr. Prairie Band Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Yakama KS 1 21ST NATIVES (D2) R. Lyons AZ Chemehuevi, Hualapai 6 BIRD CITY (D1) M. Barney Navajo AZ 2 AK-CHIN (D2) T. Carlyle Ak-Chin AZ 7 BLUBIRD BALLERZ (D1) B. Whitehorse Navajo UT 3 AZ FUTURE (D2) T. Blackwater Akimel O'odham, Dine, Hopi AZ 8 CHAOS (D1) D. Kohlus Cheyenne River Sioux, Standing Rock Sioux SD 4 AZ OUTLAWS (D2) S. Amador Mohave, Navajo, Chemehuevi, Digueno AZ CHEYENNEARAPAHO 9 R. Island Cheyenne Arapaho Tribes Of Oklahoma OK 5 AZ SPARTANS (D2) G. Pete Navajo AZ (D1) 10 FLIGHT 701 (D1) B. Kroupa Arikara, Hidatsa, Sioux ND 6 DJ RAP SQUAD (D2) R. Paytiamo Navajo NM 11 FMD (D1) Gerald Doka Yavapai, Pima, CRIT AZ 7 FORT YUMA (D2) D. Taylor Quechan CA 12 FORT MOJAVE (D1) J. Rodriguez Jr. Fort Mojave, Chemehuevi, Colorado River Indian Tribes CA 8 GILA RIVER (D2) R. -

AN INDEX to SONS of COLORADO 1906 - 1908 Volumes I and II

AN INDEX TO SONS OF COLORADO 1906 - 1908 Volumes I and II “A.E. Pierce’s Circulating Library”: estab. In Denver, II, #6, p. 4; “An Act”: photostat of bill est. Colorado Day, I, #10, p. 27; Abbie, G.H.: constable, (Den. Pct.), Arapahoe Co., K.T., II, #4, p. 8; Adair, Isaac (Fort Collins): obituary, II, #5, p. 21; Adams, James Barton: “The Dust of The Overland Trail,” (poem), I, #10, p. 21; “A Colorado Morning,” (poem), #11, p. 12; “The Slaughter of The Cotonwoods,” II, #1, p. 11; “It’s Easy,” (poem), #2, p. 22; “Only One Denver,” (poem), #8, p. 11; “Our Brave Old Pioneers,” (poem), #12, p. 21; Address of Welcome: by Elihu Root, at Rio de Janeiro, (reprint), I, #8, p. 17-19; “Admission Day”: celebrations, I, #2, p. 20; II, #3, p. 15-18; plans for, (ed. Den. Repub.), I, #2, p. 21; “Advertisers”: in first issue RMN, II, #6, p. 7-8; “Advertisements: misc., I, #1, p. 16; professional, #2, p. 36; #3, p. 28; “After The Verdict”: illust., I, #12, p. 37; Agriculture: dry farming methods, I, #4, p. 11-16; D.K. Wall’s experiments in, #12, p. 16; Akin, Charles B. (Denver): obituary, I, #11, p. 23-24; Akin, Capt. Thomas A.: sketch, I, #11, p. 23-24; Alford, Hon. N.C.: State rep. II, #8, p. 7; speaks at pioneer cel. (Ft. Collins); sketch, #9, p. 15; “Allegorical Cartoon”: pub. In Den. Mirror, by S.G. Fowler (ed); desc. II, #2, p. 9-10; Allen, Capt. Asaph: on school bd. -

SPIDER in the RIVER: a COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY of the IMPACT of the CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED on CHEYENNES and EURO- AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History Spring 4-21-2015 SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO- AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John J. Buchkoski University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Buchkoski, John J., "SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880" (2015). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 83. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880 By John J. Buchkoski A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Katrina L. Jagodinsky Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2015 SPIDER IN THE RIVER: A COMPARATIVE ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF THE IMPACT OF THE CACHE LA POUDRE WATERSHED ON CHEYENNES AND EURO-AMERICANS, 1830-1880 John Buchkoski, M.A. -

The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Final Draft Elizabeth Michell July 31 2009 An abbreviated version intended as guide for visitors OYL/iJ INTRODUCTION On late spring day visitor stands on slight rise on the banks of Big Sandy Creek from where across Cheyenne chief Black Kettles village once stood whole lot of he nothing comments laconically It is quiet place its peacefulness giving it timeless But quality the visitor is wrong and the timelessness is deceptive You can never visit the past again The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is in southeastern fifteen Colorado about miles northeast of the small town of Eads This is high plains country dusty and flat the drab greens of grass and scrub melding into the relentless browns of desiccated vegetation sand and soil The surrounding landscape is crisscrossed dirt by trails and fence lines dotted with windmills outbuildings and stock watering tanks At the site groves of cottonwoods tower along the gently sloping banks of Big Sandy Creek in fact it would be difficult to follow the stream course without the line of trees For most of the year water does not flow and the creek bed is choked with sand sagebrushes and other the site dry prairie species Though is part of shortgrass most of the land is prairie actually sandy bottomland that may eventually become It in Black Kettles tallgrass prairie was dry time and it is still dry evident by how much more sagebrush species there are now -

Update September 2018 Colorado/Cherokee Trail Chapter News and Events

Update September 2018 Colorado/Cherokee Trail Chapter News and Events Welcome New and Returning Members Bill and Sally Burr Jack and Jody Lawson Emerson and Pamela Shipe John and Susie Winner . Chapter Members Attending the 2018 Ogden, Utah Convention L-R: Gary and Ginny Dissette, Bruce and Peggy Watson, Camille Bradford, Kent Scribner, Jane Vander Brook, Chuck Hornbuckle, Lynn and Mark Voth. Photo by Roger Blair. Preserving the Historic Road Conference September 13-16 Preserving the Historic Road is the leading international conference dedicated to the identification, preservation and management of historic roads. The 2018 Conference will be held in historic downtown Fort Collins and will celebrate twenty years of advocacy for historic roads and look to the future of this important heritage movement that began in 1998 with the first conference in Los Angeles. The 2018 conference promises to be an exceptional venue for robust discussions and debates on the future of historic roads in the United States and around the globe. Don't miss important educational sessions showcasing how the preservation of historic roads contributes to the economic, transportation, recreational, and cultural needs of your community. The planning committee for Preserving the Historic Road 2018 has issued a formal Call for Papers for presentations at the September 13-16, 2018 conference. Interested professionals, academics and advocates are encouraged to submit paper abstracts for review and consideration by the planning committee. The planning committee is seeking paper abstracts that showcase a number of issues related to the historic road and road systems such as: future directions and approaches for the identification, preservation and management of historic roads to identify priorities for the next twenty years of research, advocacy and action.