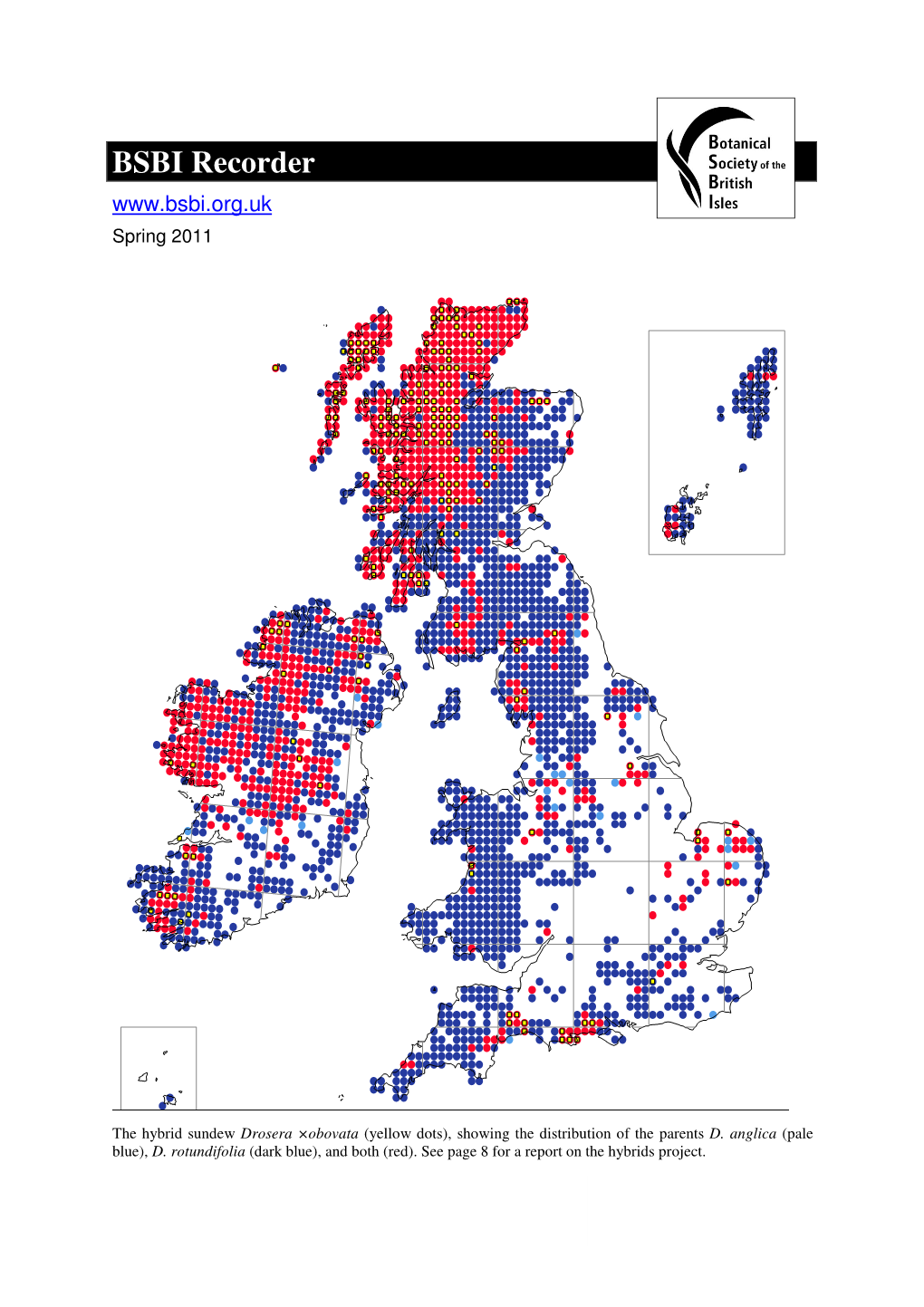

Recorder 15 (Spring 2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

Watsonia 3, 228-232

A NEW BRITISH SPECIES OF SENECIO By EFFIE M. RossER The Manchester Museum, The University, Manchester In September 1953 specimens of a large, radiate groundsel were received from Mr. H . E. Green, who had seen similar plants, growing by a roadside in Flintshire, since 1948. They could not be assigned to any described European species of Senecio and though they bore some resemblance to the hybrid S. X baxteri Druce (S. squalidus L. X S. vulgaris L.) were more robust, with larger heads and a high percentage of fertile fruits. When, in 1954, a chromosome count was made from root tips of plants grown from the Flintshire seed they were found to have the chromosome number 2n = 60; in the same year Professor S. C. Harland and Miss A. Haygarth Jackson produced a similar plant by colchicine treatment of the synthetic hybrid S . squalidus X vulgaris (2n = 30). This evidence confirmed us in the view that the plant should be described as a new species. A description follows. Senecio cambr£:nsis Rosser, sp. novo Herba (annua vel) perennis, ad 50 cm. altitudine. Caulis erectus, basi sublignosus saepe parte media dense ramosa et foliosa. Folia inferiora petiolata, superiora sessilia, auriculata; omnia alte et irregulariter pinnatifida, cum lobis distantibus, majoribus liguli formibus, minoribus lanceolatis, marginibuS" dentatis vd quandoque lobulatis; folia iuvenescentia tomentosa praesertim subtus, glabrescentia, cum axillis foliorum maturorum lanuginosis. Inflorescentia foliosa, imprimis dense corymbosa postea ramis florentibus longioribus, pedunculis tempore fructescendi longius extensis. Capitula imprimis late cylindracea (ca. 10·0 X 6·0 mm.) tempore florendi flosculorum radii nonnihil campanulata (ca. -

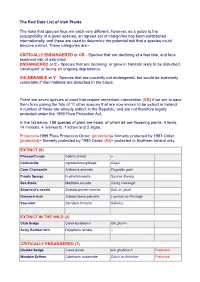

The Red Data List of Irish Plants

The Red Data List of Irish Plants The risks that species face are each very different, however, as a guide to the susceptibility of a given species, an agreed set of categories has been established internationally, and these are used to determine the potential risk that a species could become extinct. These categories are:- CRITICALLY ENDANGERED or CR - Species that are declining at a fast rate, and face imminent risk of extinction. ENDANGERED or E - Species that are declining, or grow in habitats likely to be disturbed, 'developed' or facing an ongoing degradation. VULNERABLE or V - Species that are currently not endangered, but would be extremely vulnerable if their habitats are disturbed in the future. There are seven species of plant that require immediate intervention (CR) if we are to save them from joining the fate of 11 other species that are now known to be extinct in Ireland. A number of these are already extinct in the Republic, and are not therefore legally protected under the 1999 Flora Protection Act. In the list below, 188 species of plant are listed, of which 64 are flowering plants, 4 ferns, 14 mosses, 4 liverworts, 1 lichen and 2 algae. Protected=1999 Flora Protection Order; (protected)= formerly protected by 1987 Order; {protected}= formerly protected by 1980 Order; (NI)= protected in Northern Ireland only. EXTINCT (9) Pheasant's-eye Adonis annua -- Corncockle Agrostemma githago Cogal Corn Chamomile Anthemis arvensis Fíogadán goirt Purple Spurge Euphorbia peplis Spuirse dhearg Sea Stock Matthiola sinuata Tonóg chladaigh -

Lowland Calcareous Grassland (Uk Bap Priority Habitat)

LOWLAND CALCAREOUS GRASSLAND (UK BAP PRIORITY HABITAT) Summary These are unimproved grasslands on base-rich soils in the southern and eastern Scottish lowlands. They consist of mixtures of grasses growing with a rich array of herbs including small base-tolerant herbs. These grasslands typically occur as small patches among mosaics with acid and neutral grasslands (including agriculturally improved grasslands), scrub and rock outcrops, and are most common on southerly aspects. Their total extent in Scotland was estimated in 2004 to be only 46 hectares. They are of high conservation value in being small patches of very concentrated high diversity within larger landscapes dominated by intensively managed farmland. They are home to some uncommon plant species and are an important food source for grazing mammals, invertebrates and birds. They are produced and maintained by grazing, which is needed to keep larger, more vigorous plants in check and thereby maintain high botanical diversity. What is it? Lowland calcareous grasslands are communities of thin, dry, base-rich mineral soils derived from rocks such as limestone, various igneous rocks and some sandstones. They are notable for being generally rich in species, including several small, low-grown herbs. Low shoots or mats of wild thyme Thymus polytrichus are invariably present and serve to distinguish the vegetation from neutral and acid grasslands. Some stands also contain similar low mats of common rockrose Helianthemum nummularium. The main sward is short and made up mainly of the grasses sheep’s fescue Festuca ovina, red fescue F. rubra, crested hair-grass Koeleria cristata, meadow oat-grass Helictotrichon pratense, quaking grass Briza media, spring sedge Carex caryophyllea and glaucous sedge C. -

Purple Milk-Vetch Astragalus Danicus Purple Milk-Vetch Is a Low-Growing Hairy Herb of the Pea Family (Fabaceae)

Species fact sheet Purple Milk-vetch Astragalus danicus Purple milk-vetch is a low-growing hairy herb of the pea family (Fabaceae). The pinnate leaves 3-7 cm in length are typical of the family, with hairy leaflets 5-12 mm in length. Bluish-purple pea-like flowers that are 15 mm long are gathered in short compact racemes that look like a compact flower head with stalks much thicker than the leaf stalk. Swollen seed pods are dark brown with obvious white hairs. Members of the pea family are known to provide a good nectar resource for pollinating insects. © Christian Koppitz under Creative Commons BY licence Lifecycle Purple milk-vetch is a perennial plant flowering mainly in June and July. Very little is known about its seed longevity, but the plant has reappeared on land cleared of coniferous plantation in the Norfolk Brecklands suggesting quite significant seed dormancy capacity. Habitat Its main habitats are species-rich short, dry and infertile calcareous grassland, on both limestone and chalk. The plant is also found on coastal sand-dunes and in the Brecks on inland calcareous sands. It appears to be physically rather than chemically restricted to calcareous soils and will grow on moderately acid sands/gravels as long as competition from other species is kept low, primarily by adequate grazing and maintenance of low soil nutrient status. In Scotland purple milk-vetch is also present on old red sandstone sea cliffs and machair grassland. Distribution Purple milk-vetch has inland populations in southern England in Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, the Chilterns and on the Brecklands of Norfolk and Suffolk. -

THE IRISH RED DATA BOOK 1 Vascular Plants

THE IRISH RED DATA BOOK 1 Vascular Plants T.G.F.Curtis & H.N. McGough Wildlife Service Ireland DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE 1988 ISBN 0 7076 0032 4 This version of the Red Data Book was scanned from the original book. The original book is A5-format, with 168 pages. Some changes have been made as follows: NOMENCLATURE has been updated, with the name used in the 1988 edition in brackets. Irish Names and family names have also been added. STATUS: There have been three Flora Protection Orders (1980, 1987, 1999) to date. If a species is currently protected (i.e. 1999) this is stated as PROTECTED, if it was previously protected, the year(s) of the relevant orders are given. IUCN categories have been updated as follows: EN to CR, V to EN, R to V. The original (1988) rating is given in brackets thus: “CR (EN)”. This takes account of the fact that a rare plant is not necessarily threatened. The European IUCN rating was given in the original book, here it is changed to the UK IUCN category as given in the 2005 Red Data Book listing. MAPS and APPENDIX have not been reproduced here. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are most grateful to the following for their help in the preparation of the Irish Red Data Book:- Christine Leon, CMC, Kew for writing the Preface to this Red Data Book and for helpful discussions on the European aspects of rare plant conservation; Edwin Wymer, who designed the cover and who, as part of his contract duties in the Wildlife Service, organised the computer applications to the data in an efficient and thorough manner. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Abaimov, A.P., 2010: Geographical Distribution and Ackerly, D.D., 2009: Evolution, origin and age of Genetics of Siberian Larch Species. In Osawa, A., line ages in the Californian and Mediterranean flo- Zyryanova, O.A., Matsuura, Y., Kajimoto, T. & ras. Journal of Biogeography 36, 1221–1233. Wein, R.W. (eds.), Permafrost Ecosystems. Sibe- Acocks, J.P.H., 1988: Veld Types of South Africa. 3rd rian Larch Forests. Ecological Studies 209, 41–58. Edition. Botanical Research Institute, Pretoria, Abbadie, L., Gignoux, J., Le Roux, X. & Lepage, M. 146 pp. (eds.), 2006: Lamto. Structure, Functioning, and Adam, P., 1990: Saltmarsh Ecology. Cambridge Uni- Dynamics of a Savanna Ecosystem. Ecological Stu- versity Press. Cambridge, 461 pp. dies 179, 415 pp. Adam, P., 1994: Australian Rainforests. Oxford Bio- Abbott, R.J. & Brochmann, C., 2003: History and geography Series No. 6 (Oxford University Press), evolution of the arctic flora: in the footsteps of Eric 308 pp. Hultén. Molecular Ecology 12, 299–313. Adam, P., 1994: Saltmarsh and mangrove. In Groves, Abbott, R.J. & Comes, H.P., 2004: Evolution in the R.H. (ed.), Australian Vegetation. 2nd Edition. Arctic: a phylogeographic analysis of the circu- Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, pp. marctic plant Saxifraga oppositifolia (Purple Saxi- 395–435. frage). New Phytologist 161, 211–224. Adame, M.F., Neil, D., Wright, S.F. & Lovelock, C.E., Abbott, R.J., Chapman, H.M., Crawford, R.M.M. & 2010: Sedimentation within and among mangrove Forbes, D.G., 1995: Molecular diversity and deri- forests along a gradient of geomorphological set- vations of populations of Silene acaulis and Saxi- tings. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 02 April 2020 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Walter, Greg M. and Abbott, Richard J. and Brennan, Adrian C. and Bridle, Jon R. and Chapman, Mark and Clark, James and Filatov, Dmitry and Nevado, Bruno and Ortiz Barrientos, Daniel and Hiscock, Simon J. (2020) 'Senecio as a model system for integrating studies of genotype, phenotype and tness.', New phytologist., 226 (2). pp. 326-344. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16434 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2020 The Authors. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Review Tansley review Senecio as a model system for integrating studies of genotype, phenotype and fitness Authors for correspondence: Greg M. Walter1 , Richard J. Abbott2 , Adrian C. Brennan3 , Greg M. -

Extrazonal Steppes of Forest Belt on Eastern Macroslope of the Urals

BIO Web of Conferences 16, 00043 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20191600043 Results and Prospects of Geobotanical Research in Siberia Extrazonal steppes of forest belt on eastern macroslope of the Urals Natalya Zolotareva1, , Andrey Korolyuk2 1Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology UB RAS, 620144, 8 Marta Str., 202, Ekaterinburg, Russia 2Central Siberian botanical garden SB RAS, 630090, Zolotodolinskaya Str., 101, Novosibirsk, Russia Abstract. Extrazonal steppes of forest belt on eastern macroslope of the Middle and South Urals have small coenotic diversity. The most part of studied communities are petrophytic steppes on outcrops, which determine regional features of plant cover and provide habitats to rare, endemic and relict plant species. Petrophytic steppes correspond to order Helictotricho- Stipetalia, meadow steppes and xeric meadows, shrub thickets correspond to order Brachypodietalia pinnati (class Festuco-Brometea). Extrazonal steppe is characteristic vegetation element of forest belt of the Middle and South Urals. In the Middle Urals the steppes occur on basic and ultrabasic outcrops till the southern boundary of middle taiga. In boreal zone of the South Urals the steppes are found mainly on the hyperbasites of the eastern mountain ranges. The main part of studied communities are petrophytic steppes on outcrops and a little part are meadow steppes and xeric meadows on gentle slopes. The information about steppes of forest belt of the Urals is fragmentary [1, 2, 3]. The aim of our research was to investigate the diversity of extrazonal steppe communities of forest belt of the Urals on the territory of Sverdlovsk and Chelyabinsk Regions. The dataset includes 595 relevés collected in the forest belt of the Middle and South Urals. -

II: the Origin of S

Received 20 September 1991 Heredity 69 (1992) 112—121 Genetical Society of Great Britain Molecular systematics of the genus Seneclo L. II: The origin of S. vulgar/s L. STEPHEN A. HARRIS & RUTH INGRAM Department of Biology and Predilnical Medicine, Sir Harold Mitchell Building. University of St Andrews, St Andrews, Fife KY16 9TH, Scotland Theorigin of Senecio vulgaris L. and the relationship of its two subspecies, ssp. vulgaris and ssp. denticulatus (0. F. Muell.) P. D. Sell, are examined using nuclear ribosomal and chioroplast DNA analyses. No evidence was found to support either an allopolyploid or an autopolyploid origin of S. vulgaris, although it would appear that S. vernalis Waldst. & Kit, is not one of the progenitor taxa. Two results of particular interest were found: (i) the apparent identity of the chioroplast genomes of S. vulgaris ssp. vulgaris and S. squalidus L. and (ii) the divergence of the chloroplast genomes of ssp. vulgaris and Ainsdale ssp. denticulatus by at least eight site mutations. These results are discussed in the light of evidence derived from morphological, cytological and allozyme studies. Keywords:Asteraceae,molecular variation, Senecio vulgaris ssp. vulgaris, S. vulgaris ssp. denti- culatus. Introduction characteristically spathulate leaf shape (Allen, 1967; Kadereit, 1984b). Seneciovulgaris L., the common groundsel, is one of Within Senecio vulgaris ssp. vulgaris, two varieties the most widespread annual/ephemeral species in are recognized: var. vulgaris, the more frequent non- Britain. Taxonomically two subspecies are recognized, radiate variety and var. hibernicus, an inland radiate which differ ecologically. Senecio vulgaris ssp. vu/guns variety which has increased in frequency in recent is the common weedy groundsel associated with dis- years. -

Plant Communities with Naturalized Elaeagnus Angustifolia L. As a New

Acta Biologica Sibirica 7: 49–61 (2021) doi: 10.3897/abs.7.e58204 https://abs.pensoft.net RESEARCH ARTICLE Plant communities with naturalized Elaeagnus angustifolia L. as a new vegetation element in Altai Krai (Southwestern Siberia, Russia) Alena A. Shibanova1, Natalya V. Ovcharova1 1 Altai State University, 61 Lenina Prospect, Barnaul, 656049, Russia Corresponding author: Alena A. Shibanova ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. German | Received 1 September 2020 | Accepted 29 January 2021 | Published 13 April 2021 http://zoobank.org/1B70B70D-7F9C-4CEB-907A-7FA39D1446A1 Citation: Shibanova AA, Ovcharova NV (2021) Plant communities with naturalized Elaeagnus angustifolia L. as a new vegetation element in Altai Krai (Southwestern Siberia, Russia). Acta Biologica Sibirica 7: 49–61 https://doi. org/10.3897/abs.7.e58204 Abstract Elaeagnus angustifolia L. (Russian olive) is a deciduous small tree or large multi-stemmed shrub that becomes invader in different countries all other the world. It is potentially invasive in some regions of Russia. In the beginning of 20th century, it was introduced to the steppe region of Altai Krai (Rus- sia, southwestern Siberia) to prevent wind erosion. During last 20 years, Russian olive starts to create its own natural stands and to influence on native vegetation. This article presents the results of eco- coenotic survey of natural plant communities dominated by Elaeagnus angustifolia L. first described for Siberia and the analysis of their possible syntaxonomic position. The investigation conducted during summer season 2012 in the steppe region of Altai Krai allows revealing one new for Siberia association Elytrigio repentis–Elaeagnetum angustifoliae and no-ranged community Bromopsis inermis–Elae- agnus angustifolia which were included to the Class Nerio–Tamaricetea, to the Order Tamaricetalia ramosissimae. -

Using Genomic Techniques to Investigate Interspecific Hybridisation and Genetic Diversity in Senecio

Using genomic techniques to investigate interspecific hybridisation and genetic diversity in Senecio Matt Hegarty, Aberystwyth University Why are hybridisation and polyploidy important? • Hybridisation can serve as a source of genetic novelty. • This can result in adaptive divergence and thus speciation. • It is predicted that ~70% of higher plants have undergone at least one round of genome duplication over their evolutionary history. • Approximately 15% of speciation events involve a change in ploidy. • It is estimated that the majority of polyploid species are the result of interspecific hybridisation. • Many of the world's most successful crop species are polyploids (bread wheat, coffee, cotton, sugarcane, maize) and often significantly outperform their diploid relatives. Hybrid speciation in Senecio: the homoploid origin of Senecio squalidus Senecio aethnensis 2n = 20 X Senecio squalidus 2n = 20 Abbott et al. (2000) Senecio chrysanthemifolius Watsonia 23: 123-138 2n = 20 Hybrid speciation in Senecio: the allopolyploid origin of S. cambrensis X Senecio squalidus Senecio vulgaris Diploid, SI Tetraploid, SC Senecio x baxteri Known to have Triploid, sterile occurred at least Chromosome doubling TWICE Senecio cambrensis Hexaploid, fertile, SC Previous work - transcriptomic analysis of interspecific hybrids • Constructed cDNA libraries from capitulum and mature flower buds for each of the parental and hybrid species (excl. S. x baxteri). • 1056 clones per library used to create custom cDNA microarrays for gene expression comparisons. • Libraries sequenced via Sanger sequencing - 11K sequences stored at http://www.seneciodb.org. • Expression analysis performed to compare parents with both natural and resynthesised hybrids. • Results show extreme changes to gene expression in a nonadditive manner - that is, hybrids are not merely the average of their parents.