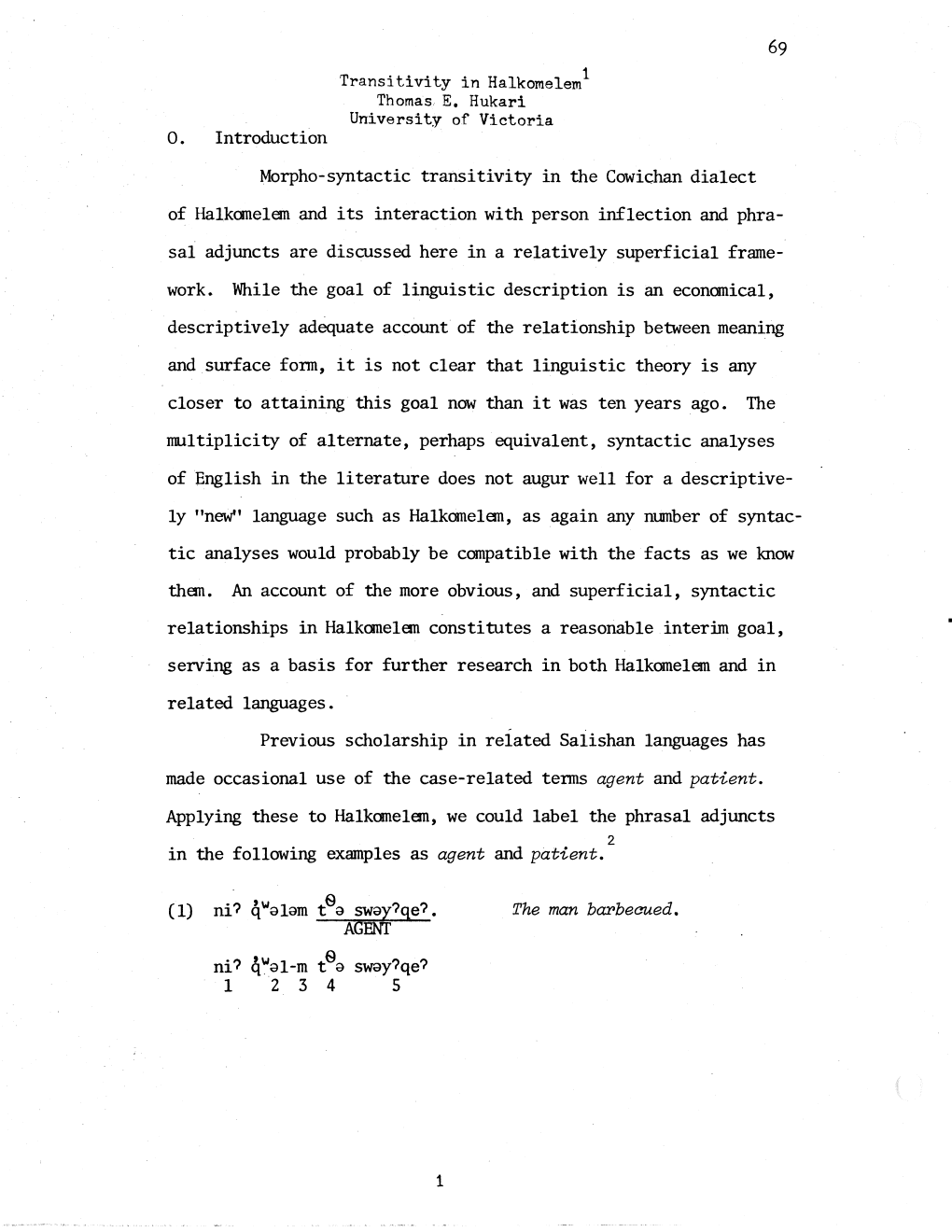

O. Introduction Morpho-Syntactic Transitivity in the Cowichan Dialect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Corpus Study of Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Diglossic Speech in Cairene Arabic

CORPUS STUDY OF TENSE, ASPECT, AND MODALITY IN DIGLOSSIC SPEECH IN CAIRENE ARABIC BY OLA AHMED MOSHREF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Elabbas Benmamoun, Chair Professor Eyamba Bokamba Professor Rakesh M. Bhatt Assistant Professor Marina Terkourafi ABSTRACT Morpho-syntactic features of Modern Standard Arabic mix intricately with those of Egyptian Colloquial Arabic in ordinary speech. I study the lexical, phonological and syntactic features of verb phrase morphemes and constituents in different tenses, aspects, moods. A corpus of over 3000 phrases was collected from religious, political/economic and sports interviews on four Egyptian satellite TV channels. The computational analysis of the data shows that systematic and content morphemes from both varieties of Arabic combine in principled ways. Syntactic considerations play a critical role with regard to the frequency and direction of code-switching between the negative marker, subject, or complement on one hand and the verb on the other. Morph-syntactic constraints regulate different types of discourse but more formal topics may exhibit more mixing between Colloquial aspect or future markers and Standard verbs. ii To the One Arab Dream that will come true inshaa’ Allah! عربية أنا.. أميت دمها خري الدماء.. كما يقول أيب الشاعر العراقي: بدر شاكر السياب Arab I am.. My nation’s blood is the finest.. As my father says Iraqi Poet: Badr Shaker Elsayyab iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I’m sincerely thankful to my advisor Prof. Elabbas Benmamoun, who during the six years of my study at UIUC was always kind, caring and supportive on the personal and academic levels. -

Serial Verb Constructions: Argument Structural Uniformity and Event Structural Diversity

SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTIONS: ARGUMENT STRUCTURAL UNIFORMITY AND EVENT STRUCTURAL DIVERSITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Melanie Owens November 2011 © 2011 by Melanie Rachel Owens. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/db406jt2949 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Beth Levin, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Joan Bresnan I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Vera Gribanov Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Abstract Serial Verb Constructions (SVCs) are constructions which contain two or more verbs yet behave in every grammatical respect as if they contain only one. -

Syntactic Change and the Rise of Transitivity

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2017 Syntactic Change and the Rise of Transitivity James Lavine Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Lavine, James. "Syntactic Change and the Rise of Transitivity." Studies in Polish Linguistics (2017) : 173-198. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studies in Polish Linguistics vol. 12,11, 2017,2016, issue 3, pp. 173–198 doi:10.4467/23005920SPL.17.009.720110.4467/23005920SPL.17.006.7199 www.ejournals.eu/SPL James E. Lavine Bucknell University Syntactic Change and the Rise of Transitivity: The Case of the Polish and Ukrainian -no/-to Construction1 Abstract This paper analyzes the historical divergence of predicates marked with old passive neuter -no/-to in Polish and Ukrainian. It is argued that the locus of change leading to the rise of the transitivity property involved a rearrangement of morphologically-eroded voice mor- phology. Despite the surface similarity of the Polish and Ukrainian constructions, their di- vergent distribution in the modern languages indicates that grammaticalization of the old passive morpheme proceeded along different pathways, implicating the internal structure of vP, and creating new accusative case-assigning possibilities. Keywords syntactic change, voice, passive, -no/-to construction, v-heads, accusative, natural force causers, Polish, Ukrainian Streszczenie Artykuł przedstawia analizę różnic w rozwoju form predykatów z wykładnikami strony biernej w rodzaju nijakim -no/-to w języku polskim i ukraińskim. -

Problems in Defining a Prototypical Transitive Sentence Typologically

PROBLEMS IN DEFINING A PROTOTYPICAL TRANSITIVE SENTENCE TYPOLOGICALLY Seppo Kittilei Department of General Linguistics Horttokuja 2 20014 University of Turku FINLAND Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is trying to show that the concept of the prototypical transitive sentence is very useful in the study of transitivity, but is as such not so unproblematic as has often been assumed. This is achieved by presenting examples from different languages that show the weaknesses of the "traditional" prototype. The prototype proposed here remains, however, a tentative one, because there are so many properties that cannot be described typologically because of their language-specific nature. 1. INTRODUCTION Transitivity has been defined in many different ways during the history of linguistics. Traditionally transitivity was understood to be a semantic phenomenon: Transitive sentences were sentences which describe events that involve a transfer of energy from subject to object (e.g. 'he killed the man'). Structurally these are mostly sentences with a grammatical subject and a direct (accusative) object (at least in the languages that were the targets of description). In the golden era of formal grammars transitivity became a purely formal concept: Verbs (or more rarely sentences) with a direct object were classified as transitive and those without one as intransitive without taking their semantics into account (see e.g. Jacobsen 1985:89 [4]). Formal definitions very rarely allow any intermediate forms, i.e. every transitive sentence is equally prototypical (because there are no adequate criteria by means of which the prototypicality could be measured). Therefore, the concept of a prototypical transitive sentence is irrelevant in the formal descriptions. -

Transitivity and Transitivity Alternations in Rawang and Qiang Randy J

Workshop on Tibeto-Burman Languages of Sichuan November 21-24, 2008 Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica Transitivity and transitivity alternations in Rawang and Qiang Randy J. LaPolla La Trobe University [email protected] 1. Introduction This paper is more about presenting phenomena and questions related to the concept of transitivity in Tibeto-Burman languages that I hope will stimulate discussion, rather than presenting strong conclusions. Sections 2 and 3 present alternative analyses of transitivity and questions about transitivity in two Tibeto-Burman languages I have worked on. In Section 4 I discuss some general issues about transitivity. 2. Rawang 2.1 Introduction • Rawang (Rvwang [r'w]): Tibeto-Burman language spoken in far north of Kachin State, Myanmar. Data from the Mvtwang (Mvt River) dialect.1 (Morse 1962, 1963, 1965; LaPolla 2000, 2006, to appear a, to appear b; LaPolla & Poa 2001; LaPolla & Yang 2007). • Verb-final, agglutinative, both head marking and dependent marking. • Verbs can take hierarchical person marking, aspect marking, directional marking (which also marks aspect in some cases), and tense marking. • All verbs clearly distinguished (even in citation) by their morphology in terms of what has been analysed as transitivity, and there are a number of different affixes for increasing or decreasing valency (see LaPolla 2000 on valency-changing derivations). Citation form is third person non- past affirmative/declarative: • Intransitives: non-past affirmative/declarative particle () alone in the non past (e.g. ngø 'to cry') and the intransitive past tense marker (-ı) in past forms (with third person argument); they can be used transitively only when they take valency-increasing morphological marking (causative, benefactive). -

Transitivity and Its Reflections on Some Areas of Grammar Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi

A. Can / Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi XXI (1), 2008, 43-68 Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi http://kutuphane. uludag. edu. tr/Univder/uufader. htm Transitivity and its Reflections on Some Areas of Grammar Abdullah Can Uludağ Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi [email protected] Abstract. Traditionally verbs can be classified into transitive and intransitive verbs according to complementation and consistent with this classification, verbs that do not require an obligatory object complement while forming clauses are labeled as intransitive verbs. In early 1980s, as a further classification, intransitive verbs were divided into separate sub- classes on the basis of their semantic and syntactic aspects. This study briefly explores the distinctive characteristics of two sub-classes of intransitive verbs, namely unergatives (e.g. “walk”, “smile”, “dream”, “swim”) and unaccusatives (e.g., “appear”, “emerge”, “exist”, “occur”) by comparing and contrasting their “Lexical-Semantic Representations” and “Argument Structures”, and examines how these differences between two sub-classes of intransitives affect various areas of grammar such as formation of -er nominals, adjectives and interpretation of pronoun “they”. At the end of the review, the findings are connected with grammar teaching briefly within the framework of Ausubel’s Meaningful Learning Theory. Key Words: Transitivity, unaccusative verbs, English Grammar. Özet. Fiiller geleneksel biçimde, aldıkları tamamlayıcılara göre geçişli ve geçişsiz olarak sınıflandırılırken, zorunlu tamamlayıcı olarak nesne almadan -

Conjugation Class and Transitivity in Kipsigis Maria Kouneli, University of Leipzig [email protected]

April 22nd, 2021 Workshop on theme vowels in V(P) structure and beyond University of Graz Conjugation class and transitivity in Kipsigis Maria Kouneli, University of Leipzig [email protected] 1 Introduction • Research on conjugation classes and theme vowels has mostly focused on Indo- European languages, even though they are not restricted to this language family (see Oltra-Massuet 2020 for an overview). • The goal of this talk is to investigate the properties of inflectional classes in Kip- sigis, a Nilotic language spoken in Kenya: – in the nominal domain, the language possesses a variety of thematic suffixes with many similarities to Romance theme vowels; the theory in Oltra-Massuet & Arregi (2005) can account for their distribution – in the verbal domain, the language has two conjugation classes, which I will argue spell out little v, and are closely related to argument structure, espe- cially the causative alternation • Recent syntactic approaches to the causative alternation treat it as a Voice alterna- tion: – the causative and anticausative variants have the same vP (event) layer, but differ in the presence vs. absence of an external argument-introducing Voice head (e.g., Marantz 2013, Alexiadou et al. 2015, Wood 2015, Kastner 2016, 2017, 2018, Wood & Marantz 2017, Nie 2020, Tyler 2020). (1) a. The cup broke. Anticausative b. Mary broke the cup. Causative • I show that the causative alternation in Kipsigis cannot be (just) a Voice alterna- tion: (in)transitivity in the language is calculated at the little v level for most verbs that participate in the alternation. Roadmap: 2: Inflectional classes in Kipsigis 3: Theories of the causative alternation (with a focus on morphology) 4: More on the causative alternation in Kipsigis 5: The challenge for Voice theories 6: Conclusion 1 Maria Kouneli Theme vowels in VP structure 2 Inflectional classes in Kipsigis 2.1 Language background • Kipsigis is the major variety of Kalenjin, a dialect cluster of the Southern Nilotic branch of Nilo-Saharan. -

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity

Process Type of Angkola Language Transitivity Husniah Ramadhani Pulungan1, Riyadi Santosa1, Djatmika1, Tri Wiratno1 1Universitas Sebelas Maret, Jl. Ir. Sutami No. 36A Surakarta 57126, Indonesia Keywords: process, type, transitivity, angkola, language Abstract: Angkola language is one of the Batak language subgroups in South Tapanuli, North Sumatera, in Indonesia. This article aims to know the process type of Angkola language transitivity. It is a part of experiential meaning in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). The objectives are to find out the forms and the idiosyncratic in it. The research methodology uses Spradely method based on spoken data that is Parhuta-huta Film because this film can present language in society daily life. The finding shows that the Angkola language has six process types, namely: material process, mental process, verbal process, behavioral process, relational process, and existential process. Besides, the idiosyncratic found some unique formation clauses called in Angkola language clause. Moreover, there are some different process positioning types in each Angkola language. Some of the process is located at the beginning of the clause and that looks like a cultural habit in the society.The different process positioning shows that the Angkola people have a direct conversation culture therefore the research like this must be explored more to complete the literature in similar study. 1 INTRODUCTION name Angkola comes from the name of the river in Angkola, which is the river (stem) of Angkola. Angkola is one of Batak subgroups in South According to the story, the river named by Rajendra Tapanuli Regency, North Sumatera Province, Kola (Chola) I, ruler of the Chola Kingdom (1014- Indonesia as Batak language is divided into six 1044M) in South India when it entered through types, namely: Angkola, Karo, Mandailing, Pakpak, Padang Lawas. -

Case, Valency and Transitivity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Case, Valency and Transitivity Edited by Leonid Kulikov Leiden University Andrej Malchukov PeterdeSwart Radboud University Nijmegen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Case, Valency and Transitivity / edited by Leonid Kulikov, Andrej Malchukov and Peter de Swart. p. cm. (Studies in Language Companion Series, issn 0165–7763 ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. 1. Grammar, Comparative and general--Case. 2. Grammar, Comparative and general--Transitivity. 3. Dependency grammar. 4. Semantics. I. Kulikov, L.I. II. Mal’chukov, A.L. (Andrei L’vovich). III. Swart, Peter de. IV. Series. P240.6.C37 2006 415’.5--dc22 2006040572 isbn 90 272 3087 0 (Hb; alk. paper) © 2006 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Introduction 1. Case,valencyandtransitivity Thepresentselectionofpapersdealingwithcase,valency,andtransitivity,originated fromaconferenceonthesimilartopicheldattheUniversityofNijmegeninJune2003. -

Aspect, Modality, and Tense in Badiaranke

Aspect, Modality, and Tense in Badiaranke by Rebecca Tamar Cover A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair Professor Lev Michael Professor Alan Timberlake Spring 2010 Aspect, Modality, and Tense in Badiaranke © 2010 by Rebecca Tamar Cover 1 Abstract Aspect, Modality, and Tense in Badiaranke by Rebecca Tamar Cover Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Line Mikkelsen, Chair Most formal analyses of the semantics of tense, aspect, and modality (TAM) have been developed on the basis of data from a small number of well-studied languages. In this dissertation, I describe and analyze the TAM system of Badiaranke, an Atlantic (Niger- Congo) language spoken in Senegal, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau, which manifests several cross-linguistically unusual features. I develop a new semantic proposal for Badiaranke TAM that explains its distinctive properties while also building on the insights of earlier analyses of TAM in more commonly studied languages. Aspect in Badiaranke has two initially surprising features. First, the perfective is used to talk not only about past events (as expected), but also about present states (not expected). Second, the imperfective is used to talk not only about ongoing or habitually recurring eventualities (as expected), but also about future and epistemically probable eventualities, as well as in consequents of conditionals and counterfactuals (not expected). I develop a modal explanation of these patterns, relying on the distinction between settled pasts and branching futures (Dowty 1977, Kaufmann et al. -

Rp 4: Transitivity

RP 4: TRANSITIVITY Presented by : 陳筑婷 江姿儀 招彥甫 張若梅 1. What’s transitivity? What is its role in language? Why is it important? 5. What does the study of transitivity tell us about language universals? Presented by : 陳筑婷 What is transivity? Syntactic definition of the transitive clause: zTransitive verbs: verbs (and clauses) that have a direct object Mary cut her hair. We shouldn’t laugh at the poor. Semantic definition of the prototype transitive clause: z Agentivity the subjectÆ deliberately acting agent (volitional) ex. He built a house. zAffectedness the direct objectÆ concrete, visibly affected patient ex. She cut her hair. zPerfectivity/completeness Vt.Æ codes a bounded terminated, fast-changing event (action) that took place in real time ex. She cuts her hair. vs. She cut her hair. Non-prototypical transitive verbs are: zConforming to the syntactic structure Æ A direct object is needed. zSemantically less prototypical What is its role in language? Two arguments zTransitivity is a crucial relationship in language with a number of universally predicable consequences in grammar. zThe defining properties of transitivity are discourse-determined. Æp.290 in RP 4: The correlation of foregrounding with the maximally Transitive sentence-type is complete: all foregrounded clauses are realis and perfective; and if…. (to be continued) zThe defining properties of transitivity are discourse-determined. Æp.294 (Summary and Conclusion): … the foci of high Transitivity and low Transitivity correlate with the independent discourse notions of foregrounding and backgrounding respectively. Why is it important? zTransitivity is traditionally understood as a global property of an entire clause, such that an activity is “transferred” from an agent to a patient.