Religious Landscape and Sacred Ground

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-2019 National History Bowl Round 6

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2018-2019 Bowl Round 6 Bowl Round 6 First Quarter (1) This program was aided by the studies of research teams under Bill Moyers and Richard Goodwin. This program was first described in a speech at Ohio University, where it was claimed that \no child will go unfed, and no youngster will go unschooled." Poll taxes were outlawed under this program's Voting Rights Act. Medicaid and Medicare were established under, for ten points, what set of domestic welfare programs under Lyndon B. Johnson? ANSWER: Great Society (2) This event produced a list of banned books known as the Index Librorum Prohibitorum and defined the Canon of the Bible to include the whole of the Vulgate and exclude Third and Fourth Maccabees. The papal bull Benedictus Deus upheld the doctrines produced by this meeting, which was presided over by both Julius III and Pius IV. This meeting set the number of sacraments at 7 and condemned the 95 Theses of Martin Luther. For ten points, name this 16th century church council that denounced the Protestant Reformation. ANSWER: Council of Trent (3) Description acceptable. Planners decided to use this type of construction for Kansai International Airport to avoid noise complaints and the hassles of eminent domain. The Palm Jumeirah is this type of construction in the Persian Gulf, found near similar constructions in the shape of the countries of the world on the Dubai coastline. The Chinese \Great Wall of Sand" plans to use, for ten points, what process to build additional ports and runways in the South China Sea? ANSWER: artificial islands (accept descriptions related to \they were built on man-made islands"; accept land dredging or any other description of how an island might be built) (4) This war escalated when the desecration of the Hiera Orgas led to the passing of the harsh Megarian Decree. -

TUBERCULOSIS in GREECE an Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country by J

TUBERCULOSIS IN GREECE An Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country By J. B. McDOUGALL, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P. (Ed.), F.R.S.E.; Late Consultant in Tuberculosis, Greece, UNRRA INTRODUCTION In Greece, we follow the traditions of truly great men in all branches of science, and in none more than in the science of medicine. Charles Singer has rightly said - "Without Herophilus, we should have had no Harvey, and the rise of physiology might have been delayed for centuries. Had Galen's works not survived, Vesalius would have never reconstructed anatomy, and surgery too might have stayed behind with her laggard sister, Medicine. The Hippo- cratic collection was the necessary and acknowledged basis for the work of the greatest of modern clinical observers, Sydenham, and the teaching of Hippocrates and his school is still the substantial basis of instruction in the wards of a modern hospital." When we consider the paucity of the raw material with which the Father of Medicine had to work-the absence of the precise scientific method, a population no larger than that of a small town in England, the opposition of religious doctrines and dogma which concerned themselves largely with the healing art, and a natural tendency to speculate on theory rather than to face the practical problems involved-it is indeed remarkable that we have been left a heritage in clinical medicine which has never been excelled. Nearly 2,000 years elapsed before any really vital advances were made on the fundamentals as laid down by the Hippocratic School. -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Infrastructure & Transport

Kifissia M ETHNIKI ODOS t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e LYKOVRYSI l ANO LIOSIA i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli PL.DIMOKRATIAS LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION OTE PYRGOS NERANTZIOTISSA AG.NIKOLAOS LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN VASSILISSIS LINE 4,TENDERED NEA IONIA Maroussi PETROUPOLI IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Ionia Vrilissia OLYMPIAKO Parking Facility - Attiko Metro ILION Aghioi Anargyri STADIO Operating Parking Facility NEA NEA IONIA "®P PERISSOS FILADELFIA "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PALATIANI Nea Halkidona SIDERA SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO PATISSIA Gerakas Filothei ®P Suburban Railway o Halandri " "®P e AGHIOS Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro l HALANDRI ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU "®P Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E PARASKEVI PERISTERI KATO PATISSIA GALATSI Aghia . Paraskevi t Haidari Peristeri Psyhiko "®P M AGHIOS ELIKONOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo Psihiko HOLARGOS PALLINI Pikermi KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ATTIKI ETHNIKI AMYNA "®P AGHIA MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA PANORMOU KATEHAKI Aghia Varvara EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS "®P AGHIA VARVARA ALEXANDRAS "®P ELEONAS Papagou EXARHIA AMBELOKIPI Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA Korydallos Glyka Nera PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea Zografou SYNTAGMA ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI Rentis PETRALONA PANEPISTIMIOUPOLI NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX "®P KALITHEA TAVROS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata NEOS KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas MOSCHATO IOANNIS Peania Moschato Dafni Ymittos Kallithea Drapetsona PIRAEUS DAFNI ANO ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea Smyrni o s o I Ilioupoli AGHIOS o DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS t t THEATRO (AL. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

School Fees 2016-2017

School Fees 2016-2017 Annual Tuition Fees Year Group Total Annual Advance Due Due Due September 2016 December 2016 March 2017 Nursery & Reception €6.450 €1.200 €1.750 €1.750 €1.750 Key Stage 1 €8.600 €1.200 €2.500 €2.450 €2.450 (Years 1 & 2) Key Stage 2 €8.900 €1.200 €2.600 €2.550 €2.550 (Years 3, 4, 5 & 6) Key Stage 3 €9.900 €1.200 €2.900 €2.900 €2.900 (Years 7, 8 & 9) Key Stage 4 €10.500 €1.200 €3.100 €3.100 €3.100 (Years 10 & 11) Sixth Form €11.550 €1.200 €3.450 €3.450 €3.450 (Years 12 & 13) Mid-Year Registrations Reduced fees are charged when a pupil enters the school mid-year. Fees for mid-year registrations are calculated as follows. The percentages are charged on the full fees for the academic year. Registration In: Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% Additional Fees Registration Fee This is a one-off, non-refundable payment which guarantees the pupil’s place €1.000 in school Transportation Fees Zone A Gerakas, Pallini, Penteli, Vrilissia, Melissia, Halandri €1.700 (until Nomismatokopio), Agia Paraskevi, Maroussi Zone B Halandri (after Nomismatokopio), Maroussi (after Kifissias), € 1.850 Full transportation fees Pefki, Kifissia, Kefalari, Filothei, Psychico, Papagou, Holargos, are charged even in Likovrisi instances when one- Zone C Nea Erithrea, Politia, Ekali, Drossia, Anoixi, Krioneri, €2.000 way service is required. Metamorphosi, Patissia, Iraklio, Galatsi, Athens, Zografou, Ambelokipi Zone D Kallithea, Nea Smyrni, Faliro, Glyfada, Voula, Loutsa, €2.200 Ag. -

10Th SKIF World Championship 2009 Athens - Greece July 20 to 26, 2009 Sef Stadium ( Peace & Friendsip Staduim) N.Faliro

10th SKIF World Championship 2009 Athens - Greece July 20 to 26, 2009 Sef Stadium ( Peace & Friendsip Staduim) N.Faliro Travel Agent PHONE : +301 2109515423 AEGIS HOLIDAYS FAX : +301 2109515424 36 SIVITANIDOY STR Email : [email protected] 17676 KALLITHEA-ATHENS Web : www.agishld.gr AEGIS HOLIDAYS acting exclusive as travel partner of the Greek karate federation (SKIF.gr), has reserved rooms in several hotels in Athens , all located at a nearby walking distances to Metro and Tram stations with direction to the SEF Stadium were the games will take place. Hotels booked are of three categories : 5* , 4*SUP , 4* , 3* and accordingly room rates are applicable Depending on requests and preferences. The following rates are hereby provided: PACKAGE FOR 7 DAYS / 6 NIGHTS ON BB BASIS HOTEL RATES PER PERSON EXTRA NIGHT PER PERSON SINGLE DOUBLE TRIPLE SINGLE DOUBLE TRIPLE CAT 5* EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO 1.050.- 645.- -N/A 155.- 95.- CAT 4sup* EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO 756.- 510.- 465.- 120.- 75.- 65.- CAT 4 * EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO EURO 660.- 450.- 420.- 128.- 66.- 57.- CAT 3* EURO EURO EURO EURO 600.- 360.- 90.- 55.- Rates include • Meet and assist at Airport • Round trip transfers Airport – Hotel – Airport • Accommodation 7 days / 6 nights on Bread and Breakfast Basis WALK.DISTANCE 200-250 METERS LIST OF HOTELS BOOKED IN ATHENS SEPERATED BY REGION 100-120 METRS WALKING DISTANCES TO METRO/TRAM STATION RELEVANT HOTEL NAME AREA CAT (ABBREV ST) STATION PALACE GLYFADA 4 PARALIA 1 ST –TRAM 30-60 METERS GOLDEN SUN GLYFADA 3 PARALIA 1 ST –TRAM -

Athens Metro Lines Development Plan and the European Union Transport and Networks

Kifissia M t . P e Zefyrion Lykovrysi KIFISSIA n t LEGEND e l i Metamorfosi KAT METRO LINES NETWORK Operating Lines Pefki Nea Penteli LINE 1 Melissia PEFKI LINE 2 Kamatero MAROUSSI LINE 3 Iraklio Extensions IRAKLIO Penteli LINE 3, UNDER CONSTRUCTION NERANTZIOTISSA OTE AG.NIKOLAOS Nea LINE 2, UNDER DESIGN Filadelfia NEA LINE 4, UNDER DESIGN IONIA Maroussi IRINI PARADISSOS Petroupoli Parking Facility - Attiko Metro Ilion PEFKAKIA Nea Vrilissia Ionia ILION Aghioi OLYMPIAKO "®P Operating Parking Facility STADIO Anargyri "®P Scheduled Parking Facility PERISSOS Nea PALATIANI Halkidona SUBURBAN RAILWAY NETWORK SIDERA Suburban Railway DOUK.PLAKENTIAS Anthousa ANO Gerakas PATISSIA Filothei "®P Suburban Railway Section also used by Metro o Halandri "®P e AGHIOS HALANDRI l P "® ELEFTHERIOS ALSOS VEIKOU Kallitechnoupoli a ANTHOUPOLI Galatsi g FILOTHEI AGHIA E KATO PARASKEVI PERISTERI GALATSI Aghia . PATISSIA Peristeri P Paraskevi t Haidari Psyhiko "® M AGHIOS NOMISMATOKOPIO AGHIOS Pallini ANTONIOS NIKOLAOS Neo PALLINI Pikermi Psihiko HOLARGOS KYPSELI FAROS SEPOLIA ETHNIKI AGHIA AMYNA P ATTIKI "® MARINA "®P Holargos DIKASTIRIA Aghia PANORMOU ®P KATEHAKI Varvara " EGALEO ST.LARISSIS VICTORIA ATHENS ®P AGHIA ALEXANDRAS " VARVARA "®P ELEONAS AMBELOKIPI Papagou Egaleo METAXOURGHIO OMONIA EXARHIA Korydallos Glyka PEANIA-KANTZA AKADEMIA GOUDI Nera "®P PANEPISTIMIO MEGARO MONASTIRAKI KOLONAKI MOUSSIKIS KORYDALLOS KERAMIKOS THISSIO EVANGELISMOS ZOGRAFOU Nikea SYNTAGMA ANO ILISSIA Aghios PAGRATI KESSARIANI Ioannis ACROPOLI NEAR EAST Rentis PETRALONA NIKEA Tavros Keratsini Kessariani SYGROU-FIX KALITHEA TAVROS "®P NEOS VYRONAS MANIATIKA Spata KOSMOS Pireaus AGHIOS Vyronas s MOSCHATO Peania IOANNIS o Dafni t Moschato Ymittos Kallithea ANO t Drapetsona i PIRAEUS DAFNI ILIOUPOLI FALIRO Nea m o Smyrni Y o Î AGHIOS Ilioupoli DIMOTIKO DIMITRIOS . -

EFQM Forum Page 07 and Friends

Index Welcome Committees page 03 Dear Colleagues Organising Bodies page 04/05 About the EFQM Forum page 07 and Friends, EFQM Forum Programme page 08 Each one of us works in a business environment full of challenges and obstacles. Regardless of our specific industries, we face the common pressure for performance - the desire and the need to be the leaders in our market, to surpass Keynote Speakers page 10 our competitors, to achieve the results we seek. How does one organisation stands out among others? The EFQM Forum 2007 will address the need for high Spyros Description of Sessions page 16 performance. What does the High Performing organisation of the future look like? It is an organisation that turns its strategy into a competitive advantage by being first to the market, it provides a meaningful brand, it successfully connects its strategic Dessyllas Award Ceremony & Gala Dinner page 18 initiatives with front-line thinking, it creates flexible operations and understands the importance of the entire supply chain. Konstantinos Venues page 19 The EFQM Forum is the annual prestigious event for Business Excellence in which over 800 business leaders congregate to learn, interact and network. The Forum Lambrinopoulos focuses on the most relevant and current business topics and culminates in a gala A Few Words About Athens page 20 celebration to recognise the annual winners of the EFQM Excellence Award. This year, we have the pleasure of hosting this event in Greece where we will present top speakers and interactive sessions from a diverse and international perspective of Proposed Hotels page 22 business today. -

Poets-Garden.Pdf

SPIROS K. KARAMOUNTZOS POET’S GARDEN SPIROS K. KARAMOUNTZOS POET’S GARDEN Translation by Zacharoula Gaitanaki Poetic circle - 2 Argolikos Archival Library History & Culture Argos 2013 “POETS’ GARDEN”, poems Greek title: Σπύρος Κ. Καραμούντζος «Ο ΚΗΠΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΠΟΙΗΤΗ», ποιήματα SPIROS K. KARAMOUNTZOS 3, Asklipiou str. 15127 Melissia Attica Greece Tel.: 030-210-6134499 Mobile: 6942647461 E-mail: [email protected] English translation by Zacharoula Gaitanaki E-mail: [email protected] Cover Design - Editing of the Book: Anastasios G. Tsagos Copyright © Argolikos Archival Library History & Culture – Spiros K. Karamountzos 1st Edition: Argos, August 2013 Cover’s picture: Gustav Klimt – Farm Garden with Sunflow- ers, c. 1905 ISBN 978-960-9650-08-3 Argolikos Archival Library of History & Culture Civil no-Profiteering Society 9-11, Vas. Kontasntinou str. 21200 Argos Greece Tel: 27510 61315 – 6942 517714 www.argolikivivliothiki.gr E-mail: [email protected] Preface by Zacharoula Gaitanaki WHEN POETRY BECOMES A BEAUTIFUL GARDEN OPEN TO ALL THE PEOPLE… “Blessed poet, now and for ever, your garden is in flower, your mind creates…”. SPIROS K. KARAMOUNTZOS is a famous and charis- matic Greek poet and writer. His poetry is an open window to the world and all the people. His garden is a beautiful place too. Wan- dering in it (reading his poem by the same title), we can see a lot of trees and flowers: sunflowers, basils, carnations, geraniums, dahlia, violets, daisies, chrysanthemums, cyclamens, pomegran- ate trees, roses, vines, fir trees, almond tress, olive trees, walnut trees, fig trees, bay… “Poet’s garden is a small heaven on earth…” The harmony of colours in nature calms us, a wealth of words, feelings, memories and pictures gains our estimation. -

School Fees 2018-2019

School Fees 2018-2019 Annual Tuition Fees Year Group Total Annual Advance Due Due Due April 2018 September 2018 December 2018 March 2019 Nursery & Reception €6.450 €1.200 €1.750 €1.750 €1.750 Key Stage 1 €8.600 €1.200 €2.500 €2.450 €2.450 (Years 1 & 2) Key Stage 2 €8.900 €1.200 €2.600 €2.550 €2.550 (Years 3, 4, 5 & 6) Key Stage 3 €9.900 €1.200 €2.900 €2.900 €2.900 (Years 7, 8 & 9) Key Stage 4 €10.500 €1.200 €3.100 €3.100 €3.100 (Years 10 & 11) Sixth Form €11.550 €1.200 €3.450 €3.450 €3.450 (Years 12 & 13) Mid-Year Registrations Reduced fees are charged when a pupil enters the school mid-year. Fees for mid-year registrations are calculated as follows. The percentages are charged on the full fees for the academic year. Registration In: Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% Additional Fees Registration Fee This is a one-off, non-refundable payment which guarantees the pupil’s place €1.000 in school Transportation Fees Zone A AGIA PARASKEVI, NEA PENTELI, MELISSIA, MAROUSI €1.700 [PARADISOS, NEA LESVOS, ANAVRITA], CHALANDRI [UNTIL NOMISMATOKOPIO] Full transportation fees Zone B ALSOUPOLI, ELLINOROSON, PAPAGOU, PSYCHICO, CHOLARGOS, €1.850 are charged even in FILOTHEI, CHALANDRI [AFTER NOMISMATOKOPIO], MAROUSI, instances when one- LIKOVRISI, PEFKI, KIFISIA way service is required. Zone C ATHENS, AMPELOKIPI, NEA ERITHREA, EKALI, POLITIA, €2.000 DIONYSOS, DROSIA, ANOIXI, AGIOS STEFANOS, KRIONERI, GALATSI, METAMORFOSI, NEA IONIA, IRAKLIO, PATISSIA, ZOGRAFOU Zone D ILIOUPOLI, ARGIROUPOLI, ELLINIKO, GLYFADA, VOULA, VARI, €2.200 VARKIZA, KALLITHEA, MOSCHATO, NEA SMIRNI, NEO FALIRO, PALEO FALIRO, PIRAEUS Zone E GERAKAS, DOUKISSIS PLAKENTIAS, PATIMA CHALANDRIOU, €800 PALIA PENTELI, VRILISSIA Terms and Conditions of Payment Additional Charges The above tuition fee charges do not include: examination fees for external examinations, i.e. -

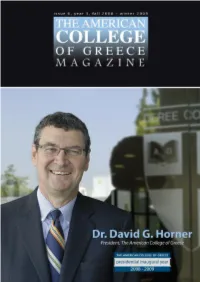

An Innovator on Campus President David G

contents An Innovator on Campus President David G. Horner, who took the reins of The American College of Greece on July 1, 2008, has made a big difference at all the institutions he has served. Now, five months into his presidency, he is on his way to doing 4 the same thing at ACG. In an interview with ACG Magazine, Dr. Horner dis - cussed the circumstances that brought him from Boston to Athens and how he views the role of the president at an institution like ACG. Literature’s Aims Dr. Ruth J. Simmons, president of Brown University in Provi - dence, Rhode Island, urged the hundreds of members of the graduating classes of Deree College, Junior College, and the Graduate School of The American College of Greece to make 12 great literature a part of their lives and use it as a source of in - spiration as they try to chart their course in the world. 21 Preventing Fire s Over the past several years, The American College of Greece has taken major steps to protect its campus and the surrounding forest of Mt. Hymettus from fire. During a recent exercise, Greek firefighters also reminded members of the College community of some of the fundamentals of fire prevention and suppression. 10 news 24 athletics 28 careers 30 culture 33 faculty notes 49 reunions 60 class notes 72 closing thoughts Searching for the Writer in You Alumnus Yorgos Kasfikis (DC‘04) returns to campus as an instructor 53 with the School of Continuing and Professional Studies THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GREECE MAGAZINE E is published biannually by the Office of Institutional Advancement and N is distributed free of charge to members of I From the Editor The American College of Greece community.