Ru Ncie E Lec Ctur Re

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

YVES CONGAR's THEOLOGY of LAITY and MINISTRIES and ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION in the UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to Th

YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Alan D. Mostrom UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2018 YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. APPROVED BY: ___________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ___________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Timothy R. Gabrielli, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader, Seton Hill University ___________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ___________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Alan D. Mostrom All rights reserved 2018 iii ABSTRACT YVES CONGAR’S THEOLOGY OF LAITY AND MINISTRIES AND ITS THEOLOGICAL RECEPTION IN THE UNITED STATES Name: Mostrom, Alan D. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. Yves Congar’s theology of the laity and ministries is unified on the basis of his adaptation of Christ’s triplex munera to the laity and his specification of ministry as one aspect of the laity’s participation in Christ’s triplex munera. The seminal insight of Congar’s adaptation of the triplex munera is illumined by situating his work within his historical and ecclesiological context. The U.S. reception of Congar’s work on the laity and ministries, however, evinces that Congar’s principle insight has received a mixed reception by Catholic theologians in the United States due to their own historical context as well as their specific constructive theological concerns over the laity’s secularity, or the priority given to lay ministry over the notion of a laity. -

Winning New Haydn Style Arrangement of Haydn's Seven Last Words by José Peris Lacasa

Winning new Haydn style arrangement of Haydn’s Seven Last Words by José Peris Lacasa ByMICHAELWHITE But Benedictdoes like to have his own musicalestablishment in the Vaticanal- The Henschel temporary RomanCatholic liturgy. around him. He has a German, Ingrid ternatelygrew Quartet VATICAN CITY and shrankduring the l5th "If you stand close to him." Mr. von Stampa,running his household.And be- stands for applause T had beena tougir week for PopeBen- and l6th centuries,sometimes waning to Kempissaid, "you seeon his facewhen fore Ms. Stamparan the papalhousehold, from Pope Benedict he edict XVI. Accusations about child the point where it was far smaller than doesn'tlike something.Four shewas a professorof music:a strange XVI, his Slearsago, on abusewithin the churchcontinued to ca- those privately maintained by individual brother and his first trip to Latin pope, reer shift but one that signals America as multiply. The focus of attack turned another cardinals.And its status rose or fell ac- the rest of the therewas a popular people thing Benedictlikes having chantthat kept personal,with claimsof cover-upsand qui- aroundhim in cordingly. audience in the Sala singing wherever theVatican. he went, and it made et interventionsin the Munich archdiocese One barometer beyond the sphere of him very uncomfortable, Benedictis deeplymusical Clementina, in the as though he decadesago, when the pope- thenknown and always purely liturgicalmusic was the fate of the wantedto run away." has been.He expresseshis conservative papal apartments. as JosephRatzinger - was its archbishop. Tor di Nona Theater,which ClementIX PopeBenedict is plain- tastes- Bach,Haydn, Mozart in sur- comfortablewith And if that weren't enough, there were - and QueenChristina of Swedenjointly es- chant and the unaccompanied prisinglyheartfelt terms. -

G:\ADULT Quizaug 2, 2020.P65

‘TEST YOUR FAITH ’ QUIZ FOR ADULTS August 2, 2020 “ O F P O P E S A ND C A R D I N A L S” Msgr. Pat Stilla (Scroll down to pages 2 & 3 for the correct answers ) T F 1. “The Vatican ” is an Italian City under the jurisdiction of the City of Rome. T F 2. St. Peter is buried under the central Papal altar in St. Peter’s Basilica. T F 3. “Roman Pontiff”, which is one of the Pope’s titles literally means, “Roman Bridge Builder”. T F 4. The Pope, who is sometimes called, the “Vicar of Christ”, is always dressed in white, because Christ wore a white robe when He walked the earth. T F 5. When one is elected Pope, his new name is chosen by the Cardinals. T F 6. After St. Peter, the name, “Peter” has never been chosen as a Pope’s name. T F 7. The name most frequently chosen by a Pope after his election, has been “Benedict”, used 16 times. T F 8. Since the Pope is not only the “Holy Father” of the entire world but also the Bishop of Rome, it is his obligation to care for the Parishioners, Bishops, Diocesan Priests and Parish Churches of the Diocese of Rome. T F 9. The Pope’s Cathedral as Bishop of Rome is St. Peter’s Basilica. T F 10. One little known title of the Pope is, “Servant of the servants of God”. T F 11. “Cardinal“ comes from a Greek word which means, a “Prince of the Church”. -

Ministry to Families Must Meet Their Real Needs, Pope Says

Ministry to families must meet their real needs, pope says VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The Catholic Church cannot claim to safeguard marriage and family life if it simply repeats its traditional teaching without supporting, encouraging and caring for real families, especially when they struggle to live up to that teaching, Pope Francis said. “It’s not enough to repeat the value and importance of doctrine if we don’t safeguard the beauty of the family and if we don’t compassionately take care of its fragility and its wounds,” the pope said March 19 in a message to a Rome conference marking the fifth anniversary of Amoris Laetitia, his 2016 exhortation of marriage and family life. The conference, sponsored by the Dicastery for Laity, the Family and Life, the Diocese of Rome and the Pontifical John Paul II Theological Institute for the Sciences of Marriage and Family, kicked off celebrations of the “Amoris Laetitia Family Year,” which will conclude June 26, 2022, at the World Meeting of Families in Rome. Pope Francis told conference participants, most of whom were watching online, that his exhortation was meant to give a starting point for a “journey encouraging a new pastoral approach to the family reality.” “The frankness of the Gospel proclamation and the tenderness of accompaniment,” he said, must go hand in hand in the Church’s pastoral approach. The task of the Church, the pope said, is to help couples and families understand “the authentic meaning of their union and their love” as a “sign and image of Trinitarian love and the alliance between Christ and his church.” The Church’s message, he said, “is a demanding word that aims to free human relationships from the slaveries that often disfigure them and render them instable: the dictatorship of emotions; the exaltation of the provisional, which discourages lifelong commitments; the predominance of individualism; (and) fear of the future.” Marriage is a part of God’s plan for individuals, is the fruit of God’s grace and is a call “to be lived with totality, fidelity and gratuity,” the pope said. -

Mustang Daily, April 6, 2007

ANGD ig\6 C A L I F C ■ POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY 2007 Today’s weather Poly drops Big West home opener The Mustang Daily asks students what V to CSUN, 8-7 Easter means to them Partly sunny IN SPO RTS, 8 Low 50° High 69‘ IN SPOTLIGHT, 4 Volume LXX, Number 113 Friday, April 6, 2007 w w w .m ustan3daiiy.com MEXA m arches in Vv. m em oiy Wq o f Chavez ■ / rfifi „ ■ -. i ■ *. » ■ PATRICK TRAUTFIELD MUSTANG DAILY To celebrate the Cesar Chavez V Honorary March, students from V Cal Poly’s Movimiento Estudiantil Xicana/o de Azdan (MEXA) walked from Dexter Lawn to the University Union on Thursday. The marchers held signs and chanted in support of immigration reform and set up a display in the UU. Scooters, motoicydes a means of saving California Senate leader seeks Taylor Moore $6,(XK) and runs approximately 70 miles to the gallon. out-of-Iraq voter initiative MUSTANG DAILY Many used cars can have the same price as a new Vespa, but Wilmore said the typical car only gets 20 miles Marcus Wohlsen With gas prices now over $3 per gallon and campus to the gallon. ASStX:iATEI) PRESS parking lots crowded, many students are now looking at ”1 save roughly $180 a month on gas using my bike,” [f else alternate modes of transporution like motorcycles and Cuesta College junior Gene Daik said. BERKELEY, Calif.— The state motor scooters. Baik owns both a sport utility vehicle and a motorcy Senate leader on Thursday worlcs, then Students who ride their motorcycles to campus ben cle and drives roughly 200 miles a week for work and announced plans for an advisory efit with closer parking spaces and $90 annual parking school. -

Treaty Between the Holy See and Italy

TREATY BETWEEN THE HOLY SEE AND ITALY IN THE NAME OF THE MOST HOLY TRINITY Whereas: The Holy See and Italy have recognized the desirability of eliminating every existing reason for dissension between them by arriving at a definitive settlement of their reciprocal relations, one which is consistent with justice and with the dignity of the two Parties and which, by assuring to the Holy See in a permanent manner a position in fact and in law which guarantees it absolute independence for the fulfilment of its exalted mission in the world, permits the Holy See to consider as finally and irrevocably settled the “Roman Question”, which arose in 1870 by the annexation of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy under the Dynasty of the House of Savoy; Since, in order to assure the absolute and visible independence of the Holy See, it is required that it be guaranteed an indisputable sovereignty even in the international realm, it has been found necessary to create under special conditions Vatican City, recognizing the full ownership and the exclusive and absolute power and sovereign jurisdiction of the Holy See over the same; His Holiness the Supreme Pontiff Pius XI and His Majesty Victor Emanuel III King of Italy have agreed to conclude a Treaty, appointing for that purpose two Plenipotentiaries, namely, on behalf of His Holiness, His Eminence Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, his Secretary of State, and on behalf of His Majesty, His Excellency Sir Benito Mussolini, Prime Minister and Head of Government; which persons, having exchanged their respective full powers, which were found to be in due and proper form, have agreed upon the following articles: Art. -

Christopher White Table of Contents

Christopher White Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Peter the “rock”? ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Churches change over time ...................................................................................................................... 6 The Church and her earthly pilgrimage .................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 The Apostle Peter (d. 64?) : First Bishop and Pope of Rome? .................................................. 11 Peter in Rome ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Yes and No .............................................................................................................................................. 13 The death of Peter .................................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2 Pope Sylvester (314-335): Constantine’s Pope ......................................................................... 16 Constantine and his imprint .................................................................................................................... 17 “Remembering” Sylvester ...................................................................................................................... -

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear?

How Do Cardinals Choose Which Hat to Wear? By Forrest Wickman March 12, 2013 6:30 PM A cardinal adjusts his mitre cap. Photo by Alessia Pierdomenico/Reuters One-hundred-fifteen Roman Catholic cardinals locked themselves up in the Vatican today to select the church’s next pope. In pictures of the cardinals, they were shown wearing a variety of unusual hats. How do cardinals choose their hats? To suit the occasion, to represent their homeland, or, sometimes, to make a personal statement. Cardinals primarily wear one of three different types. The most basic hat is a skullcap called the zucchetto (pl. zucchetti), which is a simple round hat that looks like a beanie or yarmulke. Next is the collapsible biretta, a taller, square-ridged cap with three peaks on top. There are certain times when it’s customary to put on the biretta, such as when entering and leaving church for Mass, but it’s often just personal preference. Cardinals wear both of these hats in red, which symbolizes how each cardinal should be willing to spill his blood for the church. (The zucchetto is actually worn beneath the biretta.) Some cardinals also wear regional variations on the hat, such as the Spanish style, which features four peaks instead of three. On special occasions, such as when preparing to elect the next leader of their church, they may also wear a mitre, which is a tall and usually white pointed hat. The mitre is the same style of cap commonly worn by the pope, and it comes in three different styles with varying degrees of ornamentation, according to the occasion. -

A Christian's Pocket Guide to the Papacy.Indd

1 WE HAVE A POPE! HABEMUS PAPAM! THE PAPAL OFFICE THROUGH HIS TITLES AND SYMBOLS ‘Gaudium Magnum: Habemus Papam!’ Th ese famous words introduce a new Pope to the world. Th ey are spoken to the throng that gathers in St. Peter’s Square to celebrate the occasion. Th e Pope is one of the last examples of absolute sovereignty in the modern world and embodies one of history’s oldest institutions. Th e executive, legislative, and juridical powers are all concentrated in the Papal offi ce. Until the Pope dies or resigns, he remains the Pope with all his titles and privileges. Th e only restriction on A CChristian'shristian's PPocketocket GGuideuide ttoo tthehe PPapacy.inddapacy.indd 1 22/9/2015/9/2015 33:55:42:55:42 PPMM 2 | A CHRISTIAN’S POCKET GUIDE TO THE PAPACY his power is that he cannot choose his own successor. In other words, the papacy is not dynastic. Th is task belongs to the College of electing Cardinals, that is, cardinals under eighty years old. Th ey gather to elect a new Pope in the ‘Conclave’ (from the Latin cum clave, i.e. locked up with a key), located in the Sistine Chapel. If the Pope cannot choose his own successor he can, nonetheless, choose those who elect. A good starting point for investigating the signifi cance of the Papacy is the 1994 Catechism of the Catholic Church. It is the most recent and comprehensive account of the Roman Catholic faith. Referring to the offi ce of the Pope, the Catechism notes in paragraph 882 that ‘the Roman Pontiff , by reason of his offi ce as Vicar of Christ, and as pastor of the entire Church has full, supreme, and universal power over the whole Church, a power which he can always exercise unhindered.’3 Th is brief sentence contains an apt summary of what the history and offi ce of the papacy are all about. -

Selecting a Pontiff

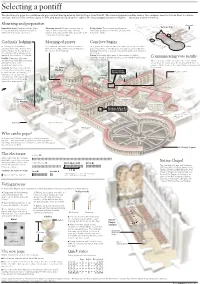

Selecting a pontiff The election of a pope is a centuries-old process that was updated in 1996 by Pope John Paul II. The church’s highest-ranking clerics, the cardinals, meet to vote in what is called a conclave. Selection by conclave dates to 1271, and was instituted as the result of the longest papal vacancy in history — two years and nine months. Mourning and preparation City wall Vatican City Immediate steps: Cardinals initiate plans Mourning period: Funeral rites are said for Voting starts: The conclave must begin no for the funeral and then the conclave to each of nine consecutive days after the fewer than 15 and no more than 20 days after determine the pope’s successor. funeral; they may provide hints about the state the pope’s death. of the church and its needs. Cardinals’ lodging Morning of prayer Conclave begins In a change from tradition, The cardinals assemble on the conclave’s As a group, the cardinals swear an oath of secrecy. Each then Detailed cardinals will not be locked in the first day for a Mass that is closely watched places his hands on the Gospels and adds a personal promise. Sistine Chapel for the duration of for clues to their thinking. Secrecy: The room is cleared of nonparticipants and entrances the conclave. They will spend the are sealed. nights at the House of St. Martha. Voting: May begin right away. If the number of eligible Communicating vote results Facility: Five-story, 131-room cardinals voting is divisible by three, a two-thirds majority plus residence hall with 108 suites and one vote is required. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1.