William Roblin: the Last Man Hanged in Pembrokeshire (1821)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

Item 5 - Report on Planning Applications

Item 5 - Report on Planning Applications Application Ref: NP/19/0665/FUL Case Officer Kate Attrill Applicant Mr & Mrs J & C Evans Agent Mr A Vaughan-Harries, Hayston Development & Planning Proposal Change of use of Linked Granny Annexe to Holiday Let Site Location Red Houses, The Rhos, Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, SA62 4AN Grid Ref 99751465 Date Valid 11-Dec-2019 Target Date 10-Jun-2020 This application was originally brought to Committee due to the Officer's recommendation differing to that of the Community Council. A cooling-off period was invoked following the vote at the 29th January 2020 Development Management Committee as approval of the application would be contrary to the adopted Local Development Plan The application was placed on the agenda for the committee meeting of 18th March 2020, which was cancelled due to Covid19. Since that time, the Inspector's final report on LDP2 has been received from Welsh Government and is now a material consideration. However LDP 1 remains the current adopted Local Development Plan until such time LDP2 is formally adopted. The report has been amended to reflect updates and further information received since 18th March 2020. Consultee Response Uzmaston, Boulston & Slebech C C: Supporting - At their 19th September 2019 meeting, and subsequent after resubmission, Uzmaston Boulston Slebech Community Council agreed to support this application. This support is in regard to economic grounds, benefits to the community and recognition that The Rhos is a centre for tourist destination. Members noted that: This particular application is fully accessible for people with disabilities, which is in short supply locally and throughout Pembrokeshire. -

The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2011 No. 683 (W.101) LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WALES The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011 Made - - - - 7 March 2011 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales has, in accordance with sections 54(1) and 58(1) of the Local GovernmentAct 1972(1), submitted to the Welsh Ministers a report dated April 2010 on its review of, and proposals for, communities within the County of Pembrokeshire. The Welsh Ministers have decided to give effect to those proposals with modifications. More than six weeks have elapsed since those proposals were submitted to the Welsh Ministers. The Welsh Ministers make the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred on the Secretary of State by sections 58(2) and 67(5) of the Local Government Act 1972 and now vested in them(2). Title and commencement 1.—(1) The title of this Order is The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011. (2) Articles 4, 5 and 6 of this Order come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on 15 October 2011; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2012. (3) For all other purposes, this Order comes into force on 1 April 2011, which is the appointed day for the purposes of the Regulations. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “existing” (“presennol”), in relation to a local government or electoral area, means that area as it exists immediately before the appointed day; “Map A” (“Map A”), “Map B” (“Map B”), “Map C” (“Map C”), “Map D” (“Map D”), “Map E” (“Map E”), “Map F” (“Map F”), “Map G” (“Map G”), “Map H” (“Map H”), “Map I” (“Map (1) 1972 c. -

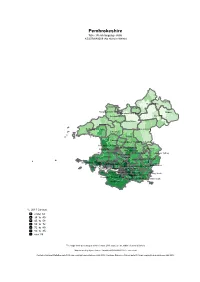

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St. -

Existing Electoral Arrangements

COUNTY OF PEMBROKESHIRE EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP Page 1 2012 No. OF ELECTORS PER No. NAME DESCRIPTION ELECTORATE 2012 COUNCILLORS COUNCILLOR 1 Amroth The Community of Amroth 1 974 974 2 Burton The Communities of Burton and Rosemarket 1 1,473 1,473 3 Camrose The Communities of Camrose and Nolton and Roch 1 2,054 2,054 4 Carew The Community of Carew 1 1,210 1,210 5 Cilgerran The Communities of Cilgerran and Manordeifi 1 1,544 1,544 6 Clydau The Communities of Boncath and Clydau 1 1,166 1,166 7 Crymych The Communities of Crymych and Eglwyswrw 1 1,994 1,994 8 Dinas Cross The Communities of Cwm Gwaun, Dinas Cross and Puncheston 1 1,307 1,307 9 East Williamston The Communities of East Williamston and Jeffreyston 1 1,936 1,936 10 Fishguard North East The Fishguard North East ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,473 1,473 11 Fishguard North West The Fishguard North West ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,208 1,208 12 Goodwick The Goodwick ward of the Community of Fishguard and Goodwick 1 1,526 1,526 13 Haverfordwest: Castle The Castle ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,651 1,651 14 Haverfordwest: Garth The Garth ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,798 1,798 15 Haverfordwest: Portfield The Portfield ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,805 1,805 16 Haverfordwest: Prendergast The Prendergast ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,530 1,530 17 Haverfordwest: Priory The Priory ward of the Community of Haverfordwest 1 1,888 1,888 18 Hundleton The Communities of Angle. -

JOSEPH MATTHIAS of HAVERFORDWEST, PEMBROKESHIRE, 1771-1835) Luke Millar

JOSEPH MATTHIAS OF HAVERFORDWEST, PEMBROKESHIRE, 1771-1835) Luke Millar Although furniture making was the defining activity of the cabinet maker, many regional firms in fact provided a wide range of services to their communities, varying according to the size and location of the firm and the enterprise and skills of its proprietor. It can be misleading to confine one’s investigations to furniture alone, because the relative quality, size and status of the firm is reflected by all its activities. The range of activities found among firms in South West Wales in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, who defined themselves primarily as cabinet makers, covers principally upholstery (including furnishings and room decorations), joinery, building, architecture to at least a minor extent, undertaking, valuing and auctioneering. Occasionally too we find wheelwright and carriage building, timber merchant, and combinations with other businesses such as inkeeper, ironmonger, or grocer. The object of this article is to study the activities of one such firm, comparing it where appropriate with others in the same district and period. Joseph Matthias is well suited for such a study because he had a high status in his community, covered a very wide range of activities including undertaking and carriage building, and worked in a town, Haverfordwest, which was wealthy and displayed high standards in its architecture and cabinet making. In addition, when he retired from cabinet making in 1830 and sold his business, he left an inventory of the whole stock of goods and materials on his premises. This is given in its entirety at the end of this article, and reference will be made to its contents as evidence of the varied nature of his work. -

(Sm 95343 15728) Archaeological Watching Brief

HAVERFORDWEST CASTLE MEMORIAL STONE, PEMBROKESHIRE (SM 95343 15728) ARCHAEOLOGICAL WATCHING BRIEF November 2009 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For: Haverfordwest Civic Society DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2010/11 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 98687 Tachwedd 2009 November 2009 HAVERFORDWEST CASTLE MEMORIAL STONE, PEMBROKESHIRE (SM 95343 15728) ARCHAEOLOGICAL WATCHING BRIEF Gan / By ANDREW SHOBBROOK Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir Gaerfyrddin SA19 The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire 6AF SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. -

1 the NAVY in the ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Submitted by Michael James

1 THE NAVY IN THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Submitted by Michael James Lea-O’Mahoney, to the University of Exeter, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in September 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned chiefly with the military role of sea power during the English Civil War. Parliament’s seizure of the Royal Navy in 1642 is examined in detail, with a discussion of the factors which led to the King’s loss of the fleet and the consequences thereafter. It is concluded that Charles I was outmanoeuvred politically, whilst Parliament’s choice to command the fleet, the Earl of Warwick, far surpassed him in popularity with the common seamen. The thesis then considers the advantages which control of the Navy provided for Parliament throughout the war, determining that the fleet’s protection of London, its ability to supply besieged outposts and its logistical support to Parliamentarian land forces was instrumental in preventing a Royalist victory. Furthermore, it is concluded that Warwick’s astute leadership went some way towards offsetting Parliament’s sporadic neglect of the Navy. The thesis demonstrates, however, that Parliament failed to establish the unchallenged command of the seas around the British Isles. -

Report No. 39/20 National Park Authority

Report No. 39/20 National Park Authority REPORT OF PERFORMANCE AND COMPLIANCE CO-ORDINATOR SUBJECT: ANNUAL REPORT ON MEETING WELL-BEING OBJECTIVES (IMPROVEMENT PLAN PART 2) 2019/20 Under the Local Government (Wales) Measure, the Authority is required to publish an Improvement Plan Part 2 by 31st October. The Well-being of Future Generations Act 2015 also places a duty on the Authority to set out its Well-being Objectives and to demonstrate how these contribute to the Welsh Government’s seven Well-being Goals. Under the legislation each year bodies must publish an annual report showing the progress they have made in meeting their objectives. They must also demonstrate how they have applied the 5 ways of working under the sustainable development principle of Long Term, Prevention, Integration, Collaboration and Involvement. This document is both the Authority’s Improvement Plan Part 2 and its annual report on progress made against its Well-being Objectives. In order to ensure equality and conservation considerations are mainstreamed across the Authority it also acts as our annual equality report and forms one element of the Authority’s reporting on how it complies with the S6 duty under the Environment (Wales) Act 2016. The report is long but this reflects the wide range of work and activities the Authority does to contribute to delivery of its Well-being objectives and its contribution to the wider Wales Well-being Goals and National Well-being Indicators. A number of data sets included in this report have previously been reported in performance reports and have been reviewed and subsequently amended where needed. -

Pembrokeshire Castles and Historic Buildings

Pembrokeshire Castles and Historic Buildings Pembrokeshire County Council Tourism Team Wales, United Kingdom All text and images are Copyright © 2011 Pembrokeshire County Council unless stated Cover image Copyright © 2011 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or part in any form First Digital Edition 2011 Digital Edition published by Count Yourself In Table of Contents Introduction SECTION 1 – CASTLES & FORTS Carew Castle & Tidal Mill Cilgerran Castle Haverfordwest Castle Llawhaden Castle Manorbier Castle Narberth Castle Nevern Castle Newport Castle Pembroke Castle Picton Castle & Woodland Gardens Roch Castle Tenby Castle Wiston Castle SECTION 2 - MUSEUMS Carew Cheriton Control Tower Castell Henllys Flying Boat Centre Gun Tower Museum Haverfordwest Museum Milford Haven Heritage & Maritime Museum Narberth Museum Scolton Manor Museum & Country Park Tenby Museum & Art Gallery SECTION 3 – ANCIENT SITES AND STANDING STONES Carreg Samson Gors Fawr standing stones Parcymeirw standing stones Pentre Ifan SECTION 4 – HISTORIC CATHEDRALS & CHURCHES Caldey Island Haverfordwest Priory Lamphey Bishop’s Palace St. Davids Bishop’s Palace St. Davids Cathedral St. Dogmaels Abbey St. Govan’s Chapel St. Mary’s Church St. Nons SECTION 5 – OTHER HISTORIC BUILDINGS Cilwendeg Shell House Hermitage Penrhos Cottage Tudor Merchant’s House Stepaside Ironworks Acknowledgements Introduction Because of its strategic position, Pembrokeshire has more than its fair share of castles and strongholds. Whether they mounted their attacks from the north or the south, when Norman barons invaded Wales after the Norman Conquest of 1066, they almost invariably ended up in West Wales and consolidated their position by building fortresses. Initially, these were simple “motte and bailey” constructions, typically built on a mound with ditches and/or wooden barricades for protection. -

“Marshal Towers” in South-West Wales: Innovation, Emulation and Mimicry

“Marshal towers” in South-West Wales: Innovation, Emulation and Mimicry “Marshal towers” in South-West Wales: Innovation, Emulation and Mimicry John Wiles THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP JOURNAL NO 27: 2013-14 181 “Marshal towers” in South-West Wales: Innovation, Emulation and Mimicry Historical context Earl William the Marshal (d. 1219) was the very flower of knighthood and England’s mightiest vassal.4 He had married the de Clare heiress in 1189 gaining vast estates that included Netherwent, with Chepstow and Usk castles, as well as the great Irish lordship of Leinster. He was granted Pembroke and the earldom that went with it at King John’s acces- sion in 1199, probably gaining possession on his first visit to his Irish lands in 1200/01.5 Although effec- tively exiled or retired to Ireland between 1207 and 1211 (Crouch, 2002, 101-115), the Marshal consoli- dated and expanded his position in south-west Wales, acquiring Cilgerran by conquest (1204) and Haver- fordwest by grant (1213), as well as gaining custody of Cardigan, Carmarthen and Gower (1214). In 1215, however, whilst the Marshal, soon to be regent, was taken up with the wars in England, a winter campaign led by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth of Gwynedd ushered in a Welsh resurgence, so that at the Marshal’s death all save the Pembroke lordship, with Haverfordwest, had been lost. Llywelyn, who had been granted cus- tody of Cardigan and Carmarthen in 1218, returned to devastate the region in 1220, again destroying many of its castles.6 Fig 1. Pembroke Castle Great Tower from the NW. -

Nicholas Bennett Records, (GB 0210 NICETT)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Nicholas Bennett Records, (GB 0210 NICETT) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/nicholas-bennett-records-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/nicholas-bennett-records-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Nicholas Bennett Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau