Number 14 March 2017 Price £4.50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEMBROKESHIRE © Lonelyplanetpublications Biggest Megalithicmonumentinwales

© Lonely Planet Publications 162 lonelyplanet.com PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK •• Information 163 porpoises and whales are frequently spotted PEMBROKESHIRE COAST in coastal waters. Pembrokeshire The park is also a focus for activities, from NATIONAL PARK hiking and bird-watching to high-adrenaline sports such as surfing, coasteering, sea kayak- The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Parc ing and rock climbing. Cenedlaethol Arfordir Sir Benfro), established in 1952, takes in almost the entire coast of INFORMATION Like a little corner of California transplanted to Wales, Pembrokeshire is where the west Pembrokeshire and its offshore islands, as There are three national park visitor centres – meets the sea in a welter of surf and golden sand, a scenic extravaganza of spectacular sea well as the moorland hills of Mynydd Preseli in Tenby, St David’s and Newport – and a cliffs, seal-haunted islands and beautiful beaches. in the north. Its many attractions include a dozen tourist offices scattered across Pembro- scenic coastline of rugged cliffs with fantas- keshire. Pick up a copy of Coast to Coast (on- Among the top-three sunniest places in the UK, this wave-lashed western promontory is tically folded rock formations interspersed line at www.visitpembrokeshirecoast.com), one of the most popular holiday destinations in the country. Traditional bucket-and-spade with some of the best beaches in Wales, and the park’s free annual newspaper, which has seaside resorts like Tenby and Broad Haven alternate with picturesque harbour villages a profusion of wildlife – Pembrokeshire’s lots of information on park attractions, a cal- sea cliffs and islands support huge breeding endar of events and details of park-organised such as Solva and Porthgain, interspersed with long stretches of remote, roadless coastline populations of sea birds, while seals, dolphins, activities, including guided walks, themed frequented only by walkers and wildlife. -

Welsh Bulletin

BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF THE BRITISH ISLES WELSH BULLETIN Editor: R. D. Pryce No. 64, WINTER 1998 Photocopy of specimens of Asplenium trichomanes subsp. pachyrachis al NMW. enlarged (xl.S) 10 show Ihe often haslate pinnae of Ihis subspecies. It is new 10 Brecs. (v.c.42); see Welsh Plant Records. 2 Contents . -.--~----- ------CO-N-TE-NT-S----~-·~~- Editorial ...................................................................................................................... 3 Progress with Atlas 2000 - the Welsh perspective Atlas 2000: Progress in v.c. 35 as November 1998 .................................................. .4 Atlas 2000: Recording in Glamorgan ........................................................................ .4 Atlas 2000: Breconshire (v.c. 42) .............................................................................. 5 Atlas 2000: 1998 recording in v.c. 43 .........................................................................6 Atlas 2000: Carmarthenshire - report on recording progress 1996 to 1998 .............. 7 Atlas 2000: Botanical recording in Pembrokeshire since 1995 .................................. 8 Atlas 2000: v.c. 46, Cardoganshire .......................................................................... 10 Atlas 2000: v.c. 47, Montgomeryshire ...................................................................... 10 Atlas 2000: Recording in Caernarfonshire (v.c. 49) ................................................. 11 Atlas 2000: v.c. 50, Denbighshire ........................................................................... -

Morloi Ble I Fynd, Beth I'w Wybod

Morlo bychan Seliwch gwylio yn llawer o hwyl, ond cadwch dawel felly rydym peidiwch â'u tarfu Morloi ble i fynd, beth i'w wybod Côd Ymddygiad Caiff Morloi eu hamddiffyn gan y gyfraith. Rydym yn ffodus i gael Morlo ifanc rhannu’r ardal arbennig yma â nhw. O’r tir: • Mae’n well gwylio’r morloi oddi ar lwybr yr arfordir – mae’n ddefnyddiol bod â sbienddrych gyda chi. Cymerwch ofal ar y clogwyni ac yn cadw proffil isel. • Cadwch draw o’r traethau ble fo morloi bychain • Gall cwˆn darfu’n fawr iawn ar y morloi • Cadwch mor dawel â phosibl • Cadwch draw os y sylwch ar arwyddion bod y morloi’n aflonyddu O’r dwˆr: • Dylech osgoi glanio ar draethau geni’r morloi bychain neu ar draethau ble fo morloi’n ymlacio • Dylech osgoi dod rhwng mam a’i un bach • Cadwch gyflymder eich cwch yn araf wrth gyrraedd a gadael y lan, a chofiwch sicrhau mai dim ond un cwch sy’n gwylio’r morloi ar y Oedolyn benyw tro • Cadwch o leiaf 20 metr i ffwrdd, ond yn ddelfrydol cadwch 50 metr i ffwrdd • Symudwch draw os y sylwch ar unrhyw arwyddion bod y morloi’n aflonyddu • Peidiwch â cheisio nofio gyda’r morloi na’u cyffwrdd na’u bwydo Nodiadau • Os oes morlo bychan ar ei ben ei hun ar draeth, fel arfer mae’n golygu bod ei fam yn y dwˆr gerllaw. Gwnewch yn siwˆr eich bod yn cadw’n ddigon pell i ffwrdd fel y gall ddod yn ôl at yr un bach pan fydd angen. -

900 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

900 bus time schedule & line map 900 Margam - Neath College via Sandƒelds Estate, View In Website Mode Baglan Dual Carriageway, Briton Ferry The 900 bus line Margam - Neath College via Sandƒelds Estate, Baglan Dual Carriageway, Briton Ferry has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Neath Abbey: 7:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 900 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 900 bus arriving. Direction: Neath Abbey 900 bus Time Schedule 37 stops Neath Abbey Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:45 AM Bus Station 1, Port Talbot Tuesday 7:45 AM Health Centre, Water Street Water Street, Port Talbot Wednesday 7:45 AM Council Depot, Aberavon Thursday 7:45 AM Water Street, Port Talbot Friday 7:45 AM Burgess Green, Aberavon Saturday Not Operational Addison Road, Aberavon Hospital Road, Aberavon 900 bus Info Sandown Road Shops, Aberavon Direction: Neath Abbey St. Paul's Road, Sandƒelds East Community Stops: 37 Trip Duration: 40 min Goya Place, Aberavon Line Summary: Bus Station 1, Port Talbot, Health Hogarth Place, Sandƒelds East Community Centre, Water Street, Council Depot, Aberavon, Burgess Green, Aberavon, Addison Road, Aberavon, Romney Road, Aberavon Hospital Road, Aberavon, Sandown Road Shops, Abbeyville Court, Sandƒelds East Community Aberavon, Goya Place, Aberavon, Romney Road, Aberavon, Sandy Ridge, Aberavon, Farm Drive, Sandy Ridge, Aberavon Sandƒelds, Briar Road, Sandƒelds, Western Avenue Sandy Ridge, Sandƒelds East Community School, Sandƒelds, Western Avenue -

Managing Online Communications and Feedback Relating to the Welsh Visitor Attraction Experience: Apathy and Inflexibility in Tourism Marketing Practice?

Managing online communications and feedback relating to the Welsh visitor attraction experience: apathy and inflexibility in tourism marketing practice? David Huw Thomas, BA, PGCE, PGDIP, MPhil Supervised by: Prof Jill Venus, Dr Conny Matera-Rogers and Dr Nicola Palmer Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the degree of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David. 2018 i ii DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for deposit in the University’s digital repository. Signed (candidate) Date 15.02.2018 iii iv Abstract Understanding of what constitutes a tourism experience has been the focus of increasing attention in academic literature in recent years. For tourism businesses operating in an ever more competitive marketplace, identifying and responding to the needs and wants of their customers, and understanding how the product or consumer experience is created is arguably essential. -

THE ROLE of GRAZING ANIMALS and AGRICULTURE in the CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: Recognising Key Environmental and Economic Benefits Delivered by Agriculture in Wales’ Uplands

THE ROLE OF GRAZING ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURE IN THE CAMBRIAN MOUNTAINS: recognising key environmental and economic benefits delivered by agriculture in Wales’ uplands Author: Ieuan M. Joyce. May 2013 Report commissioned by the Farmers’ Union of Wales. Llys Amaeth,Plas Gogerddan, Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, SY23 3BT Telephone: 01970 820820 Executive Summary This report examines the benefits derived from the natural environment of the Cambrian Mountains, how this environment has been influenced by grazing livestock and the condition of the natural environment in the area. The report then assesses the factors currently causing changes to the Cambrian Mountains environment and discusses how to maintain the benefits derived from this environment in the future. Key findings: The Cambrian Mountains are one of Wales’ most important areas for nature, with 17% of the land designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). They are home to and often a remaining stronghold of a range of species and habitats of principal importance for the conservation of biological diversity with many of these species and habitats distributed outside the formally designated areas. The natural environment is critical to the economy of the Cambrian Mountains: agriculture, forestry, tourism, water supply and renewable energy form the backbone of the local economy. A range of non-market ecosystem services such as carbon storage and water regulation provide additional benefit to wider society. Documentary evidence shows the Cambrian Mountains have been managed with extensively grazed livestock for at least 800 years, while the pollen record and archaeological evidence suggest this way of managing the land has been important in the area since the Bronze Age. -

Women in the Rural Society of South-West Wales, C.1780-1870

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870. Thomas, Wilma R How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Thomas, Wilma R (2003) Women in the rural society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42585 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Women in the Rural Society of south-west Wales, c.1780-1870 Wilma R. Thomas Submitted to the University of Wales in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History University of Wales Swansea 2003 ProQuest Number: 10805343 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

CCW Over Its 22 Year Existence

As the Countryside Council for Wales was completing its 2012-2013 programme of work towards targets agreed with Welsh Government, Chair, Members of Council and Directors felt that it would be appropriate to record key aspects of the work of CCW over its 22 year existence. This book is our way of preserving that record in a form that can be retained by staff and Council Members past and present. CCW has had to ‘learn while doing’, and in many instances what we understand today is the fruit of innovation over the past two decades. Little of the work of CCW has been done alone. Many of the achievements in which we take pride were made in the face of formidable difficulties. Rising to these challenges has been possible only because of the support, advice and active involvement of others who share our passion for the natural environment of Wales. They, like we, know that our ecosystems, and the goods and services that stem from their careful stewardship, are our most valuable asset: our life support system. Together with our many partners in non-governmental organisations, from local community groups of volunteers through to national and international conservation bodies as well as central and local government, we have endeavoured to conserve and protect the natural resources of Wales. We are therefore offering copies of this book to our partners as a tribute to their involvement in our work – a small token of our gratitude for their friendship, support and wise counsel. There is still a great deal to learn, and as we now pass the baton to the new single environment body, Natural Resources Wales, we recognise that the relationships with partners that have been invaluable to the Countryside Council for Wales will be equally crucial to our successor. -

The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. WELSH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2011 No. 683 (W.101) LOCAL GOVERNMENT, WALES The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011 Made - - - - 7 March 2011 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) and (3) The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales has, in accordance with sections 54(1) and 58(1) of the Local GovernmentAct 1972(1), submitted to the Welsh Ministers a report dated April 2010 on its review of, and proposals for, communities within the County of Pembrokeshire. The Welsh Ministers have decided to give effect to those proposals with modifications. More than six weeks have elapsed since those proposals were submitted to the Welsh Ministers. The Welsh Ministers make the following Order in exercise of the powers conferred on the Secretary of State by sections 58(2) and 67(5) of the Local Government Act 1972 and now vested in them(2). Title and commencement 1.—(1) The title of this Order is The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011. (2) Articles 4, 5 and 6 of this Order come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to the election of councillors, on 15 October 2011; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2012. (3) For all other purposes, this Order comes into force on 1 April 2011, which is the appointed day for the purposes of the Regulations. Interpretation 2. In this Order— “existing” (“presennol”), in relation to a local government or electoral area, means that area as it exists immediately before the appointed day; “Map A” (“Map A”), “Map B” (“Map B”), “Map C” (“Map C”), “Map D” (“Map D”), “Map E” (“Map E”), “Map F” (“Map F”), “Map G” (“Map G”), “Map H” (“Map H”), “Map I” (“Map (1) 1972 c. -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1. -

The-Pembrokeshire-Marine-Code.Pdf

1 Skomer Island 2 South Pembrokeshire (Area 1) 4 Ramsey Island 100m from island P MOD Danger Area Caution Stack Rocks sensitive area for cetaceans Caution Caution porpoise sensitive area sensitive area for cetaceans Harbour (N 51 deg 44.36’ W 5 deg 16.88’) 3 South Pembrokeshire (Area 2) You are welcome to land on Skomer in North Haven You are more likely to (on the right hand beach as you approach from encounter porpoise 1hr the sea) GR 735 095. Access up onto the Island is Access to either side of slack between 10am and 6pm every day except Mondays, Wick allowed Skomer Marine Nature Reserve water. Extra caution (bank holidays excluded). It’s free if you remain on during August only required in this the beach, £6 landing fee payable for access onto Broad Haven Beach area at these the Island. Please find a member of staff for an times introductory talk and stay on the paths to avoid the P puffin burrows. Skomer Warden: 07971 114302 Stackpole Head Church Rock 5 St Margarets & Caldey Island 6 The Smalls Access: Caldey is a private island owned by the Reformed Cistercian Community. Boat owners are reminded that landing on Caldey from craft Extreme caution other than those in the Caldey highly sensitive Pool is not permitted. Access may be granted on special porpoise area occasions by pre-arrangement. 100m from island T 01834 844453 minimum safe 8 Grassholm 11 Strumble Head navigable speed only, Access to Grassholm is on south going tide. restricted due to the island 7 Skokholm Island being the worlds third largest Caution gannet colony (RSPB). -

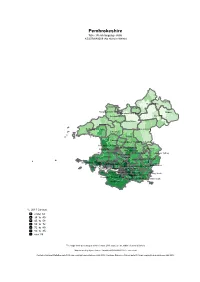

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Cilgerran St. Dogmaels Goodwick Newport Fishguard North West Fishguard North East Clydau Scleddau Crymych Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Solva Maenclochog Letterston Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Portfield Haverfordwest: Castle Narberth Martletwy Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Rural Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Johnston The Havens Llangwm Kilgetty/Begelly Amroth Milford: North Burton St. Ishmael's Neyland: West Milford: WestMilford: East Milford: Hakin Milford: Central Saundersfoot Milford: Hubberston Neyland: East East Williamston Pembroke Dock:Pembroke Market Dock: Central Carew Pembroke Dock: Pennar Penally Pembroke Dock: LlanionPembroke: Monkton Tenby: North Pembroke: St. MaryLamphey North Manorbier Pembroke: St. Mary South Pembroke: St. Michael Tenby: South Hundleton %, 2011 Census under 34 34 to 45 45 to 58 58 to 72 72 to 80 80 to 85 over 85 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Pembrokeshire Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) St. Dogmaels Cilgerran Goodwick Newport Fishguard North East Fishguard North West Crymych Clydau Scleddau Dinas Cross Llanrhian St. David's Letterston Solva Maenclochog Haverfordwest: Prendergast,Rudbaxton Wiston Camrose Haverfordwest: Garth Haverfordwest: Castle Haverfordwest: Priory Narberth Haverfordwest: Portfield The Havens Lampeter Velfrey Merlin's Bridge Martletwy Narberth Rural Llangwm Johnston Kilgetty/Begelly St. Ishmael's Milford: North Burton Neyland: West East Williamston Amroth Milford: HubberstonMilford: HakinMilford: Neyland:East East Milford: West Saundersfoot Milford: CentralPembroke Dock:Pembroke Central Dock: Llanion Pembroke Dock: Market Penally LampheyPembroke:Carew St.