Minucius Felix from T.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colin Mcallister Regnum Caelorum Terrestre: the Apocalyptic Vision of Lactantius May 2016

Colin McAllister Regnum Caelorum Terrestre: The Apocalyptic Vision of Lactantius May 2016 Abstract: The writings of the early fourth-century Christian apologist L. Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius have been extensively studied by historians, classicists, philosophers and theologians. But his unique apocalyptic eschatology expounded in book VII of the Divinae Institutiones, his largest work, has been relatively neglected. This paper will distill Lactantius’s complex narrative and summarize his sources. In particular, I investigate his chiliasm and the nature of the intermediate state, as well as his portrayal of the Antichrist. I argue that his apocalypticism is not an indiscriminate synthesis of varying sources - as it often stated - but is essentially based on the Book of Revelation and other Patristic sources. +++++ The eminent expert on all things apocalyptic, Bernard McGinn, wrote: Even the students and admirers of Lactantius have not bestowed undue praise upon him. To Rene Pichon [who wrote in 1901 what is perhaps still the seminal work on Lactantius’ thought] ‘Lactantius is mediocre in the Latin sense of the word - and also a bit in the French sense’; to Vincenzo Loi [who studied Lactantius’ use of the Bible] ‘Lactantius is neither a philosophical or theological genius nor linguistic genius.’ Despite these uneven appraisals, the writings of the early fourth-century Christian apologist L. Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius [c. 250-325] hold, it seems, a little something for everyone.1 Political historians study Lactantius as an important historical witness to the crucial transitional period from the Great Persecution of Diocletian to the ascension of Constantine, and for insight into the career of the philosopher Porphyry.2 Classicists and 1 All dates are anno domini unless otherwise indicated. -

The Protrepticus of Clement of Alexandria: a Commentary

Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui THE PROTREPTICUS OF CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA: A COMMENTARY to; ga;r yeu'do" ouj yilh'/ th'/ paraqevsei tajlhqou'" diaskedavnnutai, th'/ de; crhvsei th'" ajlhqeiva" ejkbiazovmenon fugadeuvetai. La falsedad no se dispersa por la simple comparación con la verdad, sino que la práctica de la verdad la fuerza a huir. Protréptico 8.77.3 PREFACIO Una tesis doctoral debe tratar de contribuir al avance del conocimiento humano en su disciplina, y la pretensión de que este comentario al Protréptico tenga la máxima utilidad posible me obliga a escribirla en inglés porque es la única lengua que hoy casi todos los interesados pueden leer. Pero no deja de ser extraño que en la casa de Nebrija se deje de lado la lengua castellana. La deuda que contraigo ahora con el español sólo se paliará si en el futuro puedo, en compensación, “dar a los hombres de mi lengua obras en que mejor puedan emplear su ocio”. Empiezo ahora a saldarla, empleándola para estos agradecimientos, breves en extensión pero no en sinceridad. Mi gratitud va, en primer lugar, al Cardenal Don Gil Álvarez de Albornoz, fundador del Real Colegio de España, a cuya generosidad y previsión debo dos años provechosos y felices en Bolonia. Al Rector, José Guillermo García-Valdecasas, que administra la herencia de Albornoz con ejemplar dedicación, eficacia y amor a la casa. A todas las personas que trabajan en el Colegio y hacen que cumpla con creces los objetivos para los que se fundó. Y a mis compañeros bolonios durante estos dos años. Ha sido un honor muy grato disfrutar con todos ellos de la herencia albornociana. -

Tages Against Jesus: Etruscan Religion in Late Roman Empire Dominique Briquel

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 10 Article 12 2007 Tages Against Jesus: Etruscan Religion in Late Roman Empire Dominique Briquel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Briquel, Dominique (2007) "Tages Against Jesus: Etruscan Religion in Late Roman Empire," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 10 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol10/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tages Against Jesus: Etruscan Religion in Late Roman Empire by Dominique Briquel t may seem strange to associate in this way two entities which, at first gLance, wouLd seem to have nothing in common. The civiLization of the Etruscans, which fLourished Iin ItaLy during the 1st miLLennium BC, was extinguished before the birth of Christianity, by which time Etruria had aLready been absorbed into the Larger Roman worLd in a process caLLed “Romanization.” 1 This process seems to have obLiterated the most characteristic traits of this autonomous cuLture of ancient Tuscany, a cuLture which may have been Kin to that of the Romans, but was not identicaL to it. As for Language, we can suppose that Etruscan, which is not Indo-European in origin and is therefore pro - foundLy different not onLy to Latin but to aLL other ItaLic diaLects, feLL out of use compLeteLy during the period of Augustus. One cannot, however, cLaim that aLL traces of ancient Etruria had disappeared by then. -

Adversus Paganos: Disaster, Dragons, and Episcopal Authority in Gregory of Tours

Adversus paganos: Disaster, Dragons, and Episcopal Authority in Gregory of Tours David J. Patterson Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Volume 44, 2013, pp. 1-28 (Article) Published by Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA DOI: 10.1353/cjm.2013.0000 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cjm/summary/v044/44.patterson.html Access provided by University of British Columbia Library (29 Aug 2013 02:49 GMT) ADVERSUS PAGANOS: DISASTER, DRAGONS, AND EPISCOPAL AUTHORITY IN GREGORY OF TOURS David J. Patterson* Abstract: In 589 a great flood of the Tiber sent a torrent of water rushing through Rome. According to Gregory of Tours, the floodwaters carried some remarkable detritus: several dying serpents and, perhaps most strikingly, the corpse of a dragon. The flooding was soon followed by plague and the death of a pope. This remarkable chain of events leaves us with puzzling questions: What significance would Gregory have located in such a narrative? For a modern reader, the account (apart from its dragon) reads like a descrip- tion of a natural disaster. Yet how did people in the early Middle Ages themselves per- ceive such events? This article argues that, in making sense of the disasters at Rome in 589, Gregory revealed something of his historical consciousness: drawing on both bibli- cal imagery and pagan historiography, Gregory struggled to identify appropriate objects of both blame and succor in the wake of calamity. Keywords: plague, natural disaster, Gregory of Tours, Gregory the Great, Asclepius, pagan survivals, dragon, serpent, sixth century, Rome. In 589, a great flood of the Tiber River sent a torrent of water rushing through the city of Rome. -

0200-0300 – Minucius Felix – Octavius the Octavius of Minucius

0200-0300 – Minucius Felix – Octavius The Octavius of Minucius Felix this file has been downloaded from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf04.html ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Phillip Schaff Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second MINUCIUS FELIX. 167 [Translated by the Rev. Robert Ernest Wallis, Ph.D.] 169 Introductory Note to Minucius Felix. ———————————— [A.D. 210.] Though Tertullian is the founder of Latin Christianity, his contemporary Minucius Felix gives to Christian thought its earliest clothing in Latinity. The harshness and provincialism, with the Græcisms, if not the mere Tertullianism, of Tertullian, deprive him of high claims to be classed among Latin writers, as such; but in Minucius we find, at the very fountain-head of Christian Latinity, a disciple of Cicero and a precursor of Lactantius in the graces of style. The question of his originality is earnestly debated among moderns, as it was in some degree with the ancients. It turns upon the doubt as to his place with respect to Tertullian, whose Apology he seems to quote, or rather to abridge. But to me it seems evident that his argument reflects so strikingly that of Tertullian’s Testimony of the Soul, coincident though it be with portions of the Apology, that we must make the date of the Testimony the pivot of our inquiry concerning Minucius. Now, Tertullian’s Apology preceded the Testimony, and the latter preceded the essay on the Flesh of Christ. If the Testimony was quoted or employed by Minucius, therefore, he could not have written before1708 A.D. -

Imperial Authority and the Providence of Monotheism in Orosius's Historiae Adversus Paganos

Imperial Authority and the Providence of Monotheism in Orosius’s Historiae adversus paganos Victoria Leonard B.A. (Cardiff); M.A. (Cardiff) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of History, Archaeology, and Religion Cardiff University August 2014 ii Declaration This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date ……………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………… (candidate) Date………………………… iii Cover Illustration An image of an initial 'P' with a man, thought to be Orosius, holding a book. Acanthus leaves extend into the margins. On the same original manuscript page (f. 7) there is an image of a roundel enclosing arms in the lower margin. -

A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II. by Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament, Vol. II. Author: Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener Release Date: June 28, 2011 [Ebook 36549] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A PLAIN INTRODUCTION TO THE CRITICISM OF THE NEW TESTAMENT, VOL. II.*** A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament For the Use of Biblical Students By The Late Frederick Henry Ambrose Scrivener M.A., D.C.L., LL.D. Prebendary of Exeter, Vicar of Hendon Fourth Edition, Edited by The Rev. Edward Miller, M.A. Formerly Fellow and Tutor of New College, Oxford Vol. II. George Bell & Sons, York Street, Covent Garden London, New York, and Cambridge 1894 Contents Chapter I. Ancient Versions. .3 Chapter II. Syriac Versions. .8 Chapter III. The Latin Versions. 53 Chapter IV. Egyptian Or Coptic Versions. 124 Chapter V. The Other Versions Of The New Testament. 192 Chapter VI. On The Citations From The Greek New Tes- tament Or Its Versions Made By Early Ecclesiastical Writers, Especially By The Christian Fathers. 218 Chapter VII. Printed Editions and Critical Editions. 231 Chapter VIII. Internal Evidence. 314 Chapter IX. History Of The Text. -

Chapter Sixteen. the Christian Attack on Greco-Roman Culture, Ca. 135

Chapter Sixteen The Christian Attack on GrecoRoman Culture. ca. 135 to 235 Over the course of about four hundred years, from the early second century to the early sixth, Greco-Roman civilization was replaced by Christendom. More precisely, the gods were replaced by God and by Satan. When all the other gods were driven from the field the sole remaining god ceased to be a common noun and became instead a proper name, AGod.@1 That sole remaining god was the god of the Judaeans and Christians. Satan was his diametrically opposed counterpart, the personification of Evil. The god of the Judaeans and Christians had begun in the southern Levant, during the Late Bronze Age, as Yahweh sabaoth (AYahweh of the armies@). He became the patron god of the Sons of Israel, and during the reigns of David and Solomon his cult-center was moved to Jerusalem in Judah. In the seventh century BC monolatrist priests and kings in Jerusalem made Yahweh the only god who could be worshiped in Judah and began addressing him as Adonai (Amy Lord@). For Hellenistic Judaeans he was Adonai in Hebrew, and in Greek was Kyrios (ALord@) or ho theos hypsistos (Athe highest god@). For the Pharisees and rabbis, who supposed that even the title Adonai was too holy to be uttered, he was simply ha-shem (Athe Name@). Among early Christians he was Athe Father@ or Aour Father,@ and in the fourth century he became AGod the Father,@ a title which distinguished him from AGod the Son.@ Although they addressed him with different terms, Judaeans and Christians agreed that they were invoking the same god,2 who had created the world, had wiped out almost all living things in Noah=s Flood, had been worshiped by all of Noah=s immediate descendants, but had then been forgotten by humankind until he made himself known to Abraham. -

Clement of Alexandria Epiphanius (Κατὰ Μαρκιωνιστῶν 29; Cf

Verbum et Ecclesia ISSN: (Online) 2074-7705, (Print) 1609-9982 Page 1 of 11 Original Research Documents written by the heads of the Catechetical School in Alexandria: From Mark to Clement Author: The Catechetical School in Alexandria has delivered a number of prolific scholars and writers 1 Willem H. Oliver during the first centuries of the Common Era, up to its demise by the end of the 4th century. Affiliation: These scholars have produced an extensive collection of documents of which not many are 1Department of Christian extant. Fortunately, there are many references to these documents supplying us with an idea Spirituality, Church History of the content thereof. As the author could not find one single source containing all the and Missiology, University of documents written by the heads of the School, he deemed it necessary to list these documents, South Africa, South Africa together with a short discussion of it where possible. This article only discusses the writings of Corresponding author: the following heads: Mark the Evangelist, Athenagoras, Pantaenus and Clement, covering the Willem Oliver, period between approximately 40 CE and the end of the 2nd century. The follow-up article [email protected] discusses the documents of the heads who succeeded them. Dates: Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The potential results of the proposed Received: 02 May 2017 Accepted: 16 Aug. 2017 research are a full detailed list of all the documents being written by the heads of the School in Published: 10 Nov. 2017 Alexandria. The disciplines involved are (Church) History, Theology and Antiquity. These results will make it easier for future researchers to work on these writers. -

Christian Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2007 Christian Attitudes toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D. S. Mark Veldt Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Veldt, S. Mark, "Christian Attitudes toward the Jews in the Earliest Centuries A.D." (2007). Dissertations. 925. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/925 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIAN ATTITUDES TOWARD THE JEWS IN THE EARLIEST CENTURIES A.D. by S. Mark Veldt A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dr. Paul L. Maier, Advisor Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHRISTIAN ATTITUDES TOWARD THE JEWS IN THE EARLIEST CENTURIES A.D. S. Mark Veldt, PhD . Western Michigan University, 2007 This dissertation examines the historical development of Christian attitudes toward the Jews up to c. 350 A.D., seeking to explain the origin and significance of the antagonistic stance of Constantine toward the Jews in the fourth century. For purposes of this study, the early Christian sources are divided into four chronological categories: the New Testament documents (c. -

Adversus Gentes

0200-0300 – Arnobius Afrus – Disputationum Adversus Gentes The Seven Books of Arnobius Against the Heathen (Adversus Gentes) this file has been downloaded from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf06.html ANF06. Fathers of the Third Century: Gregory Thaumaturgus, Philip Schaff Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius, and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arnobius ARNOBIUS. 403 [TRANSLATED BY ARCHDEACON HAMILTON BRYCE, LL.D., AND HUGH CAMPBELL, M.A.] 405 Introductory Notice TO Arnobius. ———————————— [A.D. 297–303.] Arnobius appears before us, not as did the earlier apologists, but as a token that the great struggle was nearing its triumphant close. He is a witness that Minucius Felix and Tertullian had not preceded him in vain. He is a representative character, and stands forth boldly to avow convictions which were, doubtless, now struggling into light from the hearts of every reflecting pagan in the empire. In all probability it was the alarm occasioned by tokens that could not be suppressed—of a spreading and deepening sense of the nothingness of Polytheism—that stimulated the Œcumenical rage of Diocletian, and his frantic efforts to crush the Church, or, rather, to overwhelm it in a deluge of flame and blood. In our author rises before us another contributor to Latin Christianity, which was still North-African in its literature, all but exclusively. He had learned of Tertullian and Cyprian what he was to impart to his brilliant pupil Lactantius. Thus the way was prepared for Augustine, by whom and in whom Latin Christianity was made distinctly Occidental, and prepared for the influence it has exerted, to this day, under the mighty prestiges of his single name. -

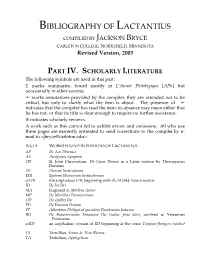

BIBLIOGRAPHY of LACTANTIUS COMPILED by JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF LACTANTIUS COMPILED BY JACKSON BRYCE CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Revised Version, 2003 PART IV. SCHOLARLY LITERATURE The following symbols are used in this part: ∑ marks summaries, found mostly in L’Année Philologique [APh] but occasionally in other sources. + marks annotations provided by the compiler; they are intended not to be critical, but only to clarify what the item is about. The presence of + indicates that the compiler has read the item; its absence may mean either that he has not, or that its title is clear enough to require no further assistance. ® indicates scholarly reviews. A work such as this cannot fail to exhibit errors and omissions. All who use these pages are earnestly entreated to send corrections to the compiler by e- mail to <[email protected]>. SIGLA WORKS FOUND IN EDITIONS OF LACTANTIUS AP De Ave Phoenice AS Aenigmata Symposii CD St. John Chrysostom, De Cœna Domini in a Latin version by Hieronymus Donatus DI Divinae Institutiones EDI Epitome Divinarum Institutionum acEDI the acephalous EDI, beginning with ch. 51 [56], Nam si iustitia ID De Ira Dei MA fragment de Motibus Animi MP De Mortibus Persecutorum OD De Opifico Dei PD De Passione Domini PT Adhortatio Philippi ad quendam Theodosium Iudæum RD De Resurrectionis Dominicæ Die (Salve, festa dies), ascribed to Venantius Fotunatus acRD an acephalous version of RD beginning at the verse Tempora florigero rutilant … TS Tertullian, Sermo de Vita Æterna TA Tertullian, Apologeticus J. BRYCE, Bibliography of Lactantius, revised 2003 Part IV. Scholarly Literature 2 VM Lorenzo Valla, De Mystero Eucharistiæ The following subtitles for the seven books of DI are often found: I.